Dreams and the Maternal Imaginary: from Nostalgic Intersubjectivity to Mourning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Oxfordshire Music Scene 29 (3.7 Mb Pdf)

ISSUE 29 / JULY 2014 / FREE @omsmagazine INSIDE LEWIS WATSON WOOD & THE PUNT REVIEWED 2014 FESTIVAL GUIDE AUDIOSCOPE ECHO & THE BUNNYMEN AND MORE! GAZ COOMBES helicopters at glastonbury, new album and south park return NEWS news y v l Oxford Oxford is a new three day event for the city, happening i g O over the weekend of 26 to 28 September. The entertainment varies w e r over the weekend, exploring the four corners of the music, arts d n A and culture world. Friday’s theme is film/shows ( Grease sing-along and Alice In Wonderland ), Saturday, a more rock - ’n’roll vibe, with former Supergrass, now solo, mainstay, Gaz Coombes, returning to his old stomping ground, as well as a selection of names from the local and national leftfield like Tunng, Pixel Fix and Dance a la Plage with much more to be announced. Sunday is a free community event involving, so far, Dancin’ Oxford and Museum of Oxford and many more. t Community groups, businesses and sports clubs wishing to t a r P get involved should get in touch via the event website n a i r oxfordoxford.co.uk. Tickets are on sale now via the website SIMPLESIMPLMPLLEE d A with a discounted weekend ticket available to Oxford residents. MINDSMMININDS Audioscope have released two WITH MELANIEMELANMELANIE C albums of exclusives and rarities AND MARCMARC ALMONDALMOND which are available to download right now. Music for a Good Home 3 consists of 31 tracks from internationally known acts including: Amon Tobin, John Parish, Future of the Left, The Original Rabbit Foot Spasm Band, Oli from Stornoway’s Esben & the Witch, Thought Forms, Count Drachma (both pictured) and Aidan Skylarkin’ are all on Chrome Hoof, Tall Firs and many music bill for this year’s Cowley Carnival , now in its 14th year, more. -

Introduction to the Psychotherapy Module

Introduction to the Psychotherapy Module Dr Lucy Buckley Aims • Know what to expect from the psychotherapy module • Know about the beginnings of psychotherapy • Have an understanding of some of Freud’s key theories • Know about Klein’s theories of the paranoid- schizoid and depressive positions • Be aware of Winnicott’s theories of early development Content • Introduction to the module • Freud and his theories ⚫ Topographical model ⚫ Structural model ⚫ Dreams and neurotic symptoms ⚫ Sexual development ⚫ Klein’s theory of the paranoid-schizoid and depressive positions ⚫ Winnicott’s concepts of primary maternal preoccupation and the ‘good enough’ mother Overview of module • Outline of different therapeutic models • Assessment • Psychotherapy evidence base • Formulation – applying psychodynamic principles in psychiatric practice Sigmund Freud, 1856-1939 ⚫ Born in Freiberg, Moravia ⚫ Moved to Vienna, studied Medicine ⚫ Studied under Charcot in Paris – use of hypnosis, interest in hysteria ⚫ Worked as neurologist, then saw more cases of psychiatric illness ⚫ Development of psychoanalysis ⚫ 1939, fled Nazi occupation of Austria, settling in London ⚫ Died soon after outbreak of Second World War Freudian theory is based on several assumptions 1) Mental life can be explained 2) The mind has a specific structure and follows intrinsic laws 3) Mental life is evolutionary and developmental 4) The mind holds unconscious forces of tremendous intensity, which, though they might not be experienced directly, hold great influence over us 5) The mind is an -

On the Postmodern Condition

1 Journal of Undergraduate Research and Scholarly Works Volume 7 December 2020 On the Postmodern Condition Sean Carroll Abstract University of Texas at San Antonio As a cultural movement, Postmodernism begun to solidify itself since the 1970s. Despite what some may say of its necessarily unstructured nature, coherent reflection about it is useful. While there is a growing literature on this topic, the present study, as suggested by David Harvey, seeks to use an historical, materialist framework, as developed by Karl Marx, to interpret postmodern culture. To do this, I began with the studies of the substructures of postmodern culture (political-economic and material conditions), and then sought to find reflective cohesion among its ‘aesthetic’ superstructures (social, philosophical, cinematic, literary, and musical) and their underlying conditions. As a result, from these studies, I found that the aesthetic sentiments of postmodern culture quite neatly map onto the material conditions, which inform its context. These sentiments imply a complicit disposition towards many aspects of late capitalism (such as consumerism and alienation). These findings are significant because it forces postmodernism to take a more honest look at itself, and become self-aware of its implications. My findings imply that if postmodern sentiments truly want to harbor an activism toward the status quo, it must first realign itself with more unifying attitudes. While a single resolution has yet to be concluded, the present study provides some general directions -

Social Dreaming Applications in Academic and Community Settings

Dreaming Psychoanalysis Forward: Social Dreaming Applications in Academic and Community Settings George Bermudez, Ph.D. Matt Silverstein, Ph.D. ―Thirdness is that quality of human existence that transcends individuality, permits and constricts that which can be known, and wraps all our sensibilities in ways that we experience as simultaneously alien as well as part of ourselves. Thirdness is the medium in which we live and that changes history, moments into time, and fragments into a whole.‖ Samuel Gerson (2009) When the third is dead: Memory, mourning, and witnessing in the aftermath of the holocaust. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 90, 1341-1357. ―And I hold that it is true that dreams are faithful interpreters of our inclinations; but there is an art required to sorting and understanding them.‖ Montaigne, ―Of Experience‖ Introduction: Psychoanalysis and Dreams: Is there a Role for “Social Dreaming?” Emphasizing what he perceives as the one hundred plus year ―love/hate‖ relationship between dreams and psychoanalysis, Lippmann (2000) decries the devalued status of dreams (theoretically and clinically) in contemporary psychoanalysis, generated by a fickle relationship that reflects the nearly universal ambivalence towards the unconscious, that unruly dimension of human experience that will not submit to our Western desires for mastery and domination. While we agree with Lippmann‘s overall assessment of our ambivalent attitudes toward dreams and the unconscious, we do not share his pessimism concerning the potential for re-integration with psychoanalysis. In contrast, it is our contention that contemporary psychoanalysis (a pluralistic conceptual landscape that parallels the complexity and ambiguity of the unconscious) offers renewed possibilities for the re-integration of dreams: for us, dreams remain the quintessential representation of the unconscious, the unformulated, the dissociated, and the repressed. -

Deconstructing Los Angeles Or a Secret Fax from Magritte Regarding Postliterate Legal Reasoning: a Critique of Legal Education

University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Volume 26 1992 Deconstructing Los Angeles or a Secret Fax from Magritte Regarding Postliterate Legal Reasoning: A Critique of Legal Education C. Garrison Lepow Loyola University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr Part of the Legal Education Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation C. G. Lepow, Deconstructing Los Angeles or a Secret Fax from Magritte Regarding Postliterate Legal Reasoning: A Critique of Legal Education, 26 U. MICH. J. L. REFORM 69 (1992). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr/vol26/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DECONSTRUCTING LOS ANGELES OR A SECRET FAX FROM MAGRITTE REGARDING POSTLITERATE LEGAL REASONING: A CRITIQUE OF LEGAL EDUCATION C. Garrison Lepow* Not only is it clear that most law students become impatient at some point during their three years of formal education, but it is clear also that how students learn the law is more the cause of their impatience than what they learn.' Moreover, others besides law students may be entitled to challenge the style of education that manufactures a lawyer-culture. If one assumes for the sake of argument that the intellectual processes of lawyers, and consequently their values, differ from those of their society, this fact does not explain the difference between legal thinking and regular thinking, or explain why there should not be harmony between the two. -

“Twin One, Twin Too” What Does It Mean to Be a Twin? a Psychoanalytic Investigation Into the Phenomenon of Twins

“Twin one, twin too” What does it mean to be a twin? A psychoanalytic investigation into the phenomenon of twins. By Emer Mc Cormack The thesis is submitted to the Quality and Qualifications Ireland (QQI) for the degree of MA in Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy from Dublin Business School, School of Arts. Supervisor: Dr. Gráinne Donohue Submitted: July 2015 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 4 ABSTRACT 6 CHAPTER ONE 7 Twin mythology Twin mythology & identity 9 Twinship 11 CHAPTER TWO 13 (Identity formation) Jacques Lacan and Melanie Klein Jacques Lacan The mirror stage Jacques Lacan: The family complexes: intrusion. Melanie Klein: Depressive position & schizoid mechanism CHAPTER THREE 23 Identity formation in twins Melanie Klein 23 Dorothy Burlingham 25 Anna Freud & Dorothy Burlingham: Hampstead Nursery’s. 27 Alessandra Piontelli 28 Sigmund Freud 30 Wilfred Bion 31 Death of a twin CHAPTER FOUR 34 Conclusion BIBLOGRAPHY 38 2 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the love and support of a number of incredibly special people. First and foremost, I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Grainne Donohue, whose expertise, understanding and patience, added considerably to my experience of writing this piece of research. A very special thank you to my class mates Laura- Mai, Hugh, Valerija, Mary and Simona “we have made it” it has been a pleasure working alongside you all over the last three years a beautiful friendship has developed between us so here’s to our further plans together. I must also acknowledge some of my very dear friends Jamie, Davina and Rachel you have all been absolute rocks to me over the last few years. -

Body Dreamwork Using Focusing to Find the Life Force Inherent in Dreams Leslie A

Body Dreamwork Using Focusing to Find the Life Force Inherent in Dreams Leslie A. Ellis Received: 16.11.2018; Revised: 17.09.2019; Accepted: 23.09.2019 ABSTRACT Finding and embodying the life force or “help” in a dream is the central practice of focusing-oriented dreamwork. This article briefly introducesfocusing (Gendlin, 1978/1981) and its application to dreamwork, and provides a case example with a transcript of how to guide a dreamer to find the life force in a distressing dream. The practice of embodying the dream’s life force provides the dreamer with an embodied resource that can be an end in itself, and can also facilitate working with the more challenging aspects of dreams and nightmares. Research and clinical examples support the use of this technique in clinical practice, and demonstrate how it can provide clinically significant relief from nightmare distress and other symptoms of PTSD. Keywords: dreamwork, focusing, nightmares, embodiment, psychotherapy International Body Psychotherapy Journal The Art and Science of Somatic Praxis Volume 18, Number 2, Fall/Winter 2019/20 pp. 75-85 ISSN 2169-4745 Printing, ISSN 2168-1279 Online © Author and USABP/EABP. Reprints and permissions [email protected] “A dream is alive,” according to Gendlin (2012), a philosopher and psychologist who developed the gentle somatic inquiry practice called focusing (1978/1981). He said that every dream contains life force—sometimes obvious and sometimes hidden— and that the main objective of working with dreams is to locate and embody this life force. This article describes how to do so, first by providing a brief introduction to focusing theory and practice and how it applies to dreamwork, then by grounding the theory through a clinical example of a dream that came to life. -

![Detailed Biography [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0053/detailed-biography-pdf-960053.webp)

Detailed Biography [PDF]

Biography Born on 3 December 1895, Anna Freud was the youngest of Sigmund and Martha Freud's six children. She was a lively child with a reputation for mischief. Freud wrote to his friend Fliess in 1899: „Anna has become downright beautiful through naughtiness..." Anna finished her education at the Cottage Lyceum in Vienna in 1912, but had not yet decided upon a career. In 1914 she travelled alone to England to improve her English. She was there when war was declared and thus became an "enemy alien". Later that year she began teaching at her old school, the Cottage Lyceum. A photo shows her with the 5th class of the school c.1918. One of her pupils later wrote: "This young lady had far more control over us than the older 'aunties'." Already in 1910 Anna had begun reading her father's work, but her serious involvement in psychoanalysis began in 1918, when her father started psychoanalyzing her. (It was not anomalous for a father to analyze his own daughter at this time, before any orthodoxy had been established.) In 1920 they both attended the International Psychoanalytical Congress at The Hague. They now had both work and friends in common. One common friend was the writer and psychoanalyst Lou Andreas- Salomé, who was once the confidante of Nietzsche and Rilke and who was to become Anna Freud's confidante in the 1920s. Through her, the Freuds also met Rilke, whose poetry Anna Freud greatly admired. Her volume of his „Buch der Bilder" bears his dedication, commemorating their first meeting. -

Obituary: W. Ernest Freud (1914 –2008)

International PSYCHOANALYSIS News Magazine of the International Psychoanalytical Association Volume 17, December 2008 Obituary: W. Ernest Freud (1914 –2008) W. Ernest Freud is best known as the 18-month-old child that Sigmund Freud observed playing ‘fort, da’ and described in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920). What is less known is that he was also Freud’s only grandchild to become a psychoanalyst. Once, when asked when his psychoanalytic training began, W. Ernest Freud replied, ‘In my mother’s belly.’ Ernest was the son of Freud’s second daughter, Sophie Freud, and Max Halberstadt, a portrait photographer. He was born Ernst Wolfgang Halberstadt on 11 March 1914 in Hamburg, Germany, but changed his name to W. Ernest Freud after the Second World War, partly because he felt his German sounding name would be a liability in post-war England and partly because he always felt closer to the Freud side of his family. When Ernest was born, Freud sent a note to Sandor Ferenczi: ‘Dear friend, Tonight (10th/11th) at 3 o’clock a little boy, my first grandchild! Very strange! An oldish feeling, respect for the wonders of sexuality!’ (Brabant, 1993, p. 545) Ernest’s life was full of tragedy and courage, love and work. He enjoyed a blissful infancy with his mother, while his father was at war; and when his father returned, Ernest experienced him as an unwelcome intruder. When Ernest was four, his brother, Heinerle, was born and he too was experienced as an intruder. After the war, Sophie became pregnant again but contracted the Spanish Flu and died, with her third baby in her womb. -

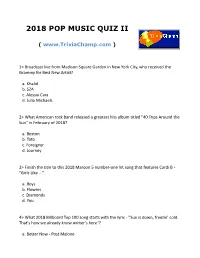

2018 Pop Music Quiz Ii

2018 POP MUSIC QUIZ II ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> Broadcast live from Madison Square Garden in New York City, who received the Grammy for Best New Artist? a. Khalid b. SZA c. Alessia Cara d. Julia Michaels 2> What American rock band released a greatest hits album titled "40 Trips Around the Sun" in February of 2018? a. Boston b. Toto c. Foreigner d. Journey 3> Finish the title to this 2018 Maroon 5 number-one hit song that features Cardi B - "Girls Like ...". a. Boys b. Flowers c. Diamonds d. You 4> What 2018 Billboard Top 100 song starts with the lyric - "Sun is down, freezin' cold. That's how we already know winter's here"? a. Better Now - Post Malone b. Nice For What - Drake c. Youngblood - 5 Seconds of Summer d. Sicko Mode - Travis Scott 5> Which American rapper had Billboard hits with the songs "Kamikaze", "The Ringer" and "Fall" in 2018? a. Lil Wayne b. Eminem c. Tupac Shakur d. 50 Cent 6> On the Billboard Hot Rock Songs chart in 2018, finish the title to this "Greta Van Fleet" hit song - "When the ...". a. Moneys Gone b. Sun Comes Down c. Levee Breaks d. Curtain Falls 7> Known as the "Queen of Soul", what artist died after a long battle with pancreatic cancer in August of 2018? a. Whitney Houston b. Aretha Franklin c. Patti LaBelle d. Tina Turner 8> Released on her debut studio album "Expectations", which American singer had a hit with the song "I'm a Mess"? a. Rita Ora b. Bebe Rexha c. -

DREAMS and Occultisml 1 [The Topic of the Last Three Paragraphs Was First Raised by Freud in Chapters II and III of Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920G)

Warning Concerning Copyright Restrictions The Copyright Law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. If electronic transmission of reserve material is used for purposes in excess of what constitutes "fair use," that user may be liable for copyright infringement. THE STANDARD EDITION OF THE COMPLETE PSYCHOLOGICAL WORKS OF SIGMUND FREUD Translated from the German under the General Editorship of JAMES STRACHEY In Collaboration with ANNA FREUD Assisted by ALIX STRACHEY and ALAN TYSON VOLUME XXII (1932-36) New Introductory Lectures on Psycho-Analysis and Other Works SIGMUND FREUD IN 1929 LONDON THE HOGARTH PRESS AND THE INSTITUTE OF PSYCHO-ANALYSIS 30 NEW INTRODUCTORY LECTURES here offering us an extreme case; but we must admit that child hood experiences, too, are of a traumatic nature, and we need not be surprised if comparatively trivial interferences with the LECTURE XXX function of dreams may arise under other conditions as well,l DREAMS AND OCCULTISMl 1 [The topic of the last three paragraphs was first raised by Freud in Chapters II and III of Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920g). Further LADIEs AND GENTLEMEN,-To-day we will proceed along a allusions to it will be found in Lecture XXXII, p. 106 below.] narrow path, but one which may lead us to a wide prospect. -

Exploring a Jungian-Oriented Approach to the Dream in Psychotherapy

Exploring a Jungian-oriented Approach to the Dream in Psychotherapy By Darina Shouldice Submitted to the Quality and Qualifications Ireland (QQI) for the degree MA in Psychotherapy from Dublin Business School, School of Arts Supervisor: Stephen McCoy June 2019 Department of Psychotherapy Dublin Business School Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction……………………………………………………………………. 1 1.1 Background and Rationale………………………………………………………………. 1 1.2 Aims and Objectives ……………………………………………………………………. 3 Chapter 2 Literature Review 2.1 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………... 4 2.2 Jung and the Dream……………………………………………………………….…….. 4 2.3 Resistance to Jung….…………………………………………………………………… 6 2.4 The Analytic Process..………………………………………………………………….. 8 2.5 The Matter of Interpretation……...……………………………………………………..10 2.6 Individuation………………………………………………………………………….. 12 2.7 Freud and Jung…………………………………….…………………………………... 13 2.8 Decline of the Dream………………………………………………………..………… 15 2.9 Changing Paradigms……………………………………………………………....….. 17 2.10 Science, Spirituality, and the Dream………………………………………….………. 19 Chapter 3 Methodology…….……………………………………...…………………….. 23 3.1 Introduction to Approach…..………………………………………………………..... 23 3.2 Rationale for a Qualitative Approach..…………………………………………..……..23 3.3 Thematic Analysis..………………………………………………………………..….. 24 3.4 Sample and Recruitment...…………………………………………………………….. 24 3.5 Data Collection..………………………………………………………………………. 25 3.6 Data Analysis..………………………………………………………………………... 26 3.7 Ethical Issues……..……………………………………………………………….…... 27 Chapter 4 Research Findings……………………………………………………………