Making a Living As a Musician in Nepal: Multiple Regimes of Value in a Changing Popular Folk Music Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Journal of Human Social Science Schemata) and Text Structure Will Be Systematically A) Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) Analyzed

OnlineISSN:2249-460X PrintISSN:0975-587X DOI:10.17406/GJHSS AStudyonJhenidahDistrict ThePoliticsofAnti-GraftWars AnalysisofMauritianExpatriates Socio-Economic&PsychologicalStatus VOLUME20ISSUE5VERSION1.0 Global Journal of Human-Social Science: C Sociology & Culture Global Journal of Human-Social Science: C Sociology & Culture Volume 2 0Issue 5 (Ver. 1.0) Open Association of Research Society Global Journals Inc. *OREDO-RXUQDORI+XPDQ (A Delaware USA Incorporation with “Good Standing”; Reg. Number: 0423089) Social Sciences. 2020. Sponsors:Open Association of Research Society Open Scientific Standards $OOULJKWVUHVHUYHG 7KLVLVDVSHFLDOLVVXHSXEOLVKHGLQYHUVLRQ Publisher’s Headquarters office RI³*OREDO-RXUQDORI+XPDQ6RFLDO 6FLHQFHV´%\*OREDO-RXUQDOV,QF Global Journals ® Headquarters $OODUWLFOHVDUHRSHQDFFHVVDUWLFOHVGLVWULEXWHG XQGHU³*OREDO-RXUQDORI+XPDQ6RFLDO 945th Concord Streets, 6FLHQFHV´ Framingham Massachusetts Pin: 01701, 5HDGLQJ/LFHQVHZKLFKSHUPLWVUHVWULFWHGXVH United States of America (QWLUHFRQWHQWVDUHFRS\ULJKWE\RI³*OREDO -RXUQDORI+XPDQ6RFLDO6FLHQFHV´XQOHVV USA Toll Free: +001-888-839-7392 RWKHUZLVHQRWHGRQVSHFLILFDUWLFOHV USA Toll Free Fax: +001-888-839-7392 1RSDUWRIWKLVSXEOLFDWLRQPD\EHUHSURGXFHG Offset Typesetting RUWUDQVPLWWHGLQDQ\IRUPRUE\DQ\PHDQV HOHFWURQLFRUPHFKDQLFDOLQFOXGLQJ SKRWRFRS\UHFRUGLQJRUDQ\LQIRUPDWLRQ G lobal Journals Incorporated VWRUDJHDQGUHWULHYDOV\VWHPZLWKRXWZULWWHQ 2nd, Lansdowne, Lansdowne Rd., Croydon-Surrey, SHUPLVVLRQ Pin: CR9 2ER, United Kingdom 7KHRSLQLRQVDQGVWDWHPHQWVPDGHLQWKLV ERRNDUHWKRVHRIWKHDXWKRUVFRQFHUQHG 8OWUDFXOWXUHKDVQRWYHULILHGDQGQHLWKHU -

Nepali Times Industry

JOYRIDE#204 9 - 15 July 2004 20 pages Rs 25 Can Deuba keep the car on the road? KUNDA DIXIT Adhikary sees it as a way to get around Maoist objections, and veryone in the new Deuba government agrees perhaps even a Eon the need to restore peace and hold elections, way to bring the they just dont agree on how to go about it. rebels to the Some want a unilateral ceasefire to pressure the negotiating table. Maoists to come to the negotiating table, others say But such a move it wont work. is sure to be opposed Peace activists have been lobbying for a ceasefire, by the army. One even if talks are not possible. They say this would close Deuba aide allow the government to address the urgent told us: Its not development and rehabilitation needs of the people. going to happen. Prime Minister Deuba has to accommodate a We dont want money to divergence of views and vested interests among the reach the Maoists. The four parties and royal nominees in his coalition. It is prime minister prefers an all- clear that on security matters, he needs the armys party presence in local bodies so that nod. One party insider told us: We have ministers the budget can be spent on development, who will all be on mobiles reporting back to their he said. bosses. Its going to be tricky. However, there are questions about The cabinets first real test is next weeks budget. whether village councils can function at a time when Already, there are signs that the UML and Deubas the Maoists have been assassinating mayors and NC-D are pulling in different directions. -

2020-Commencement-Program.Pdf

One Hundred and Sixty-Second Annual Commencement JUNE 19, 2020 One Hundred and Sixty-Second Annual Commencement 11 A.M. CDT, FRIDAY, JUNE 19, 2020 2982_STUDAFF_CommencementProgram_2020_FRONT.indd 1 6/12/20 12:14 PM UNIVERSITY SEAL AND MOTTO Soon after Northwestern University was founded, its Board of Trustees adopted an official corporate seal. This seal, approved on June 26, 1856, consisted of an open book surrounded by rays of light and circled by the words North western University, Evanston, Illinois. Thirty years later Daniel Bonbright, professor of Latin and a member of Northwestern’s original faculty, redesigned the seal, Whatsoever things are true, retaining the book and light rays and adding two quotations. whatsoever things are honest, On the pages of the open book he placed a Greek quotation from the Gospel of John, chapter 1, verse 14, translating to The Word . whatsoever things are just, full of grace and truth. Circling the book are the first three whatsoever things are pure, words, in Latin, of the University motto: Quaecumque sunt vera whatsoever things are lovely, (What soever things are true). The outer border of the seal carries the name of the University and the date of its founding. This seal, whatsoever things are of good report; which remains Northwestern’s official signature, was approved by if there be any virtue, the Board of Trustees on December 5, 1890. and if there be any praise, The full text of the University motto, adopted on June 17, 1890, is think on these things. from the Epistle of Paul the Apostle to the Philippians, chapter 4, verse 8 (King James Version). -

AIAA Fellows

AIAA Fellows The first 23 Fellows of the Institute of the Aeronautical Sciences (I) were elected on 31 January 1934. They were: Joseph S. Ames, Karl Arnstein, Lyman J. Briggs, Charles H. Chatfield, Walter S. Diehl, Donald W. Douglas, Hugh L. Dryden, C.L. Egtvedt, Alexander Klemin, Isaac Laddon, George Lewis, Glenn L. Martin, Lessiter C. Milburn, Max Munk, John K. Northrop, Arthur Nutt, Sylvanus Albert Reed, Holden C. Richardson, Igor I. Sikorsky, Charles F. Taylor, Theodore von Kármán, Fred Weick, Albert Zahm. Dr. von Kármán also had the distinction of being the first Fellow of the American Rocket Society (A) when it instituted the grade of Fellow member in 1949. The following year the ARS elected as Fellows: C.M. Bolster, Louis Dunn, G. Edward Pendray, Maurice J. Zucrow, and Fritz Zwicky. Fellows are persons of distinction in aeronautics or astronautics who have made notable and valuable contributions to the arts, sciences, or technology thereof. A special Fellow Grade Committee reviews Associate Fellow nominees from the membership and makes recommendations to the Board of Directors, which makes the final selections. One Fellow for every 1000 voting members is elected each year. There have been 1980 distinguished persons elected since the inception of this Honor. AIAA Fellows include: A Arnold D. Aldrich 1990 A.L. Antonio 1959 (A) James A. Abrahamson 1997 E.C. “Pete” Aldridge, Jr. 1991 Winfield H. Arata, Jr. 1991 H. Norman Abramson 1970 Buzz Aldrin 1968 Johann Arbocz 2002 Frederick Abbink 2007 Kyle T. Alfriend 1988 Mark Ardema 2006 Ira H. Abbott 1947 (I) Douglas Allen 2010 Brian Argrow 2016 Malcolm J. -

Multicasts, ATSC 3.0 Turn Broadcasting Into a Multichannel Platform

Perspectives from FSF Scholars October 12, 2020 Vol. 15, No. 53 Multicasts, ATSC 3.0 Turn Broadcasting Into a Multichannel Platform by Andrew Long * I. Introduction and Summary Consumers today enjoy a wealth of choices in the multichannel video programming distribution marketplace. This vibrantly competitive environment represents a dramatic departure from decades past, when claims as to the existence of bottlenecks were used to justify intrusive government intervention. One rising, and perhaps unexpected and largely unreported, source of multichannel competition is over-the-air broadcasting. Of course, dramatic changes in the media marketplace have been occurring for many years – and yet, due to its size, procedures, and inherent inertia, the "Communications Regulatory Complex" simply is unable to keep pace, especially in the face of considerable reflexive opposition by those who oppose any deregulatory changes. But with regard to broadcasting, cable, direct broadcast satellite (DBS), telco TV, and other media outlets, continued imposition of legacy regulatory restrictions of various types are in increasing tension with their First Amendment rights. Over the last ten years, the number of U.S. households that utilize an antenna to view their local television stations has increased by over a third, from nearly 11.8 million to 16 million. One explanation for that is the improved picture and audio quality that digital television (DTV) The Free State Foundation P.O. Box 60680, Potomac, MD 20859 [email protected] www.freestatefoundation.org delivers. Another is that, as consumers "cut the cord" – that is, discontinue their subscriptions to traditional multichannel video programming distributors (MVPDs) and transition to streaming options like Netflix, Hulu, Disney+, and/or Amazon Prime Video – over-the-air television provides a free means to continue to receive the popular content, both national and local, that television stations carry. -

Music As Rhetoric in Social Movements

IRA-International Journal of Management & Social Sciences ISSN 2455-2267; Vol.09, Issue 02 (November 2017) Pg. no. 71-85 Institute of Research Advances http://research-advances.org/index.php/RAJMSS 1968: Music as Rhetoric in Social Movements Mark Goodman1#, Stephen Brandon2 & Melody Fisher3 1Professor, Department of Communication, Mississippi State University, United States. 2Instructor, Department of English, Mississippi State University, United States. 3Assistant Professor, Department of Communication, Mississippi State University, United States. #corresponding author. Type of Review: Peer Reviewed. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21013/jmss.v9.v2.p4 How to cite this paper: Goodman, M., Brandon, S., Fisher, M. (2017). 1968: Music as Rhetoric in Social Movements. IRA- International Journal of Management & Social Sciences (ISSN 2455-2267), 9(2), 71-85. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.21013/jmss.v9.n2.p4 © Institute of Research Advances. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International License subject to proper citation to the publication source of the work. Disclaimer: The scholarly papers as reviewed and published by the Institute of Research Advances (IRA) are the views and opinions of their respective authors and are not the views or opinions of the IRA. The IRA disclaims of any harm or loss caused due to the published content to any party. Institute of Research Advances is an institutional publisher member of Publishers Inter Linking Association Inc. (PILA-CrossRef), USA. The institute is an institutional signatory to the Budapest Open Access Initiative, Hungary advocating the open access of scientific and scholarly knowledge. The Institute is a registered content provider under Open Access Initiative Protocol for Metadata Harvesting (OAI-PMH). -

The Intangible Cultural Heritage of Gokarneshwor

THE INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE OF GOKARNESHWOR A Thesis Submitted To Central Department of Nepalese History, Culture and Archaeology (NeHCA), Tribhuwan University In the partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master in Art (MA) Submitted By: Nittam Subedi TU Registration No: 7-2-357-17-2009 Kirtipur, Kathmandu 2016 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The thesis on “The Intangible Cultural Heritage of Gokarneshwor” is written for the partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Nepalese History Culture and Archaeology under the Department of Culture, Tribhuvan University. I hereby like to thank to my respected teachers and all those individual as well as institution for their help and support in whatever capacity possible. First of all, I would like to pay my special thanks to Professor Ms. Sabitree Mainali- the Head of Department of NeHCA, Central Department of Tribhuvan University for providing Professor Mr. Madan Rimal, as my thesis guide, who have help me to complete my thesis on time without any hassles. Meantime, I am also grateful to Professor Dr. Ms. Beena Ghimire (Poudel) for her infinite support to complete my thesis. I am also thankful to all my teachers and administration who help me to gather important information related to my thesis topic. I would like to express my indebtedness to my father Mr. Dhurba Bdr. Subedi who have introduce me the respectable person at Gokarneshwor. Also, I express my due respect to Mr. Keshab Bhatta- priest of Gokarneshwor temple; Mr. Nabaraj Poudel- member of Kal Mochan Guthi; Narayan Kaji Shrestha and Sanu Kaji Shrestha-members of Kanti Bhairav Guthi. -

2019 Annual Report

A TEAM 2019 ANNU AL RE P ORT Letter to our Shareholders Sinclair Broadcast Group, Inc. Dear Fellow Shareholders, BOARD OF DIRECTORS CORPORATE OFFICERS ANNUAL MEETING David D. Smith David D. Smith The Annual Meeting of stockholders When I wrote you last year, I expressed my sincere optimism for the future of our Company as we sought to redefine the role of a Chairman of the Board, Executive Chairman will be held at Sinclair Broadcast broadcaster in the 21st Century. Thanks to a number of strategic acquisitions and initiatives, we have achieved even greater success Executive Chairman Group’s corporate offices, in 2019 and transitioned to a more diversified media company. Our Company has never been in a better position to continue to Frederick G. Smith 10706 Beaver Dam Road grow and capitalize on an evolving media marketplace. Our achievements in 2019, not just for our bottom line, but also our strategic Frederick G. Smith Vice President Hunt Valley, MD 21030 positioning for the future, solidify our commitment to diversify and grow. As the new decade ushers in technology that continues to Vice President Thursday, June 4, 2020 at 10:00am. revolutionize how we experience live television, engage with consumers, and advance our content offerings, Sinclair is strategically J. Duncan Smith poised to capitalize on these inevitable changes. From our local news to our sports divisions, all supported by our dedicated and J. Duncan Smith Vice President INDEPENDENT REGISTERED PUBLIC innovative employees and executive leadership team, we have assembled not only a winning culture but ‘A Winning Team’ that will Vice President, Secretary ACCOUNTING FIRM serve us well for years to come. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

Rikhi Ram Music Instrument Manufacturing Company

Rikhi Ram Music Instrument Manufacturing Company https://www.indiamart.com/rikhirammusicalinstruments/ Manufacturer of sarangi, dholak and teak wood sitar. About Us Indian instruments belong to a tradition dipped in antiquity. It dates back to the Veena of Saraswati, Bansuri of Krishna and Damru of Shiva, corresponding to modern classifications of musical instruments under string, wind & percussions respectively. The journey of 'Rikhi Ram Musical Instrument Mfg.Co' started with founder Late Pt. Rikhi Ram, who was a great musicians and one of the best known musical instrument maker. Pt. Rikhi Ram's father Pt. Gobind Ram was also a musician and had inclinations towards making musical instruments and so manufacturing of musical instruments started in the family 85 years ago. Pt. Rikhi Ram learnt sitar playing from eminent musician Abdul Harim Poonchwala. Late Pt. Bishan Dass followed in his father's footsteps and started learning sitar at a very tender age under the guidance and supervision of his father. Later, he became a disciple of world renowed sitar maestro Pt. Ravi Shankar. He also worked in the maintainance cell of A.I.R. During his tenor at A.I.R he got associated with great musicians like Ustad Allauddin Khan, Ustad Hafiz Ali Khan, Ustad Vilayat Khan, Pt.Ravi Shankar and many others. From these great Ustads Bishan learnt that the primal value of a good instrument was its tonal quality. They would often discuss these aspects of an instrument and give him useful hints. "This extra interest fired my imagination and aroused in me the urge to produce quality instruments for the maestros" says Late Pt. -

SEM 63 Annual Meeting

SEM 63rd Annual Meeting Society for Ethnomusicology 63rd Annual Meeting, 2018 Individual Presentation Abstracts SEM 2018 Abstracts Book – Note to Reader The SEM 2018 Abstracts Book is divided into two sections: 1) Individual Presentations, and 2) Organized Sessions. Individual Presentation abstracts are alphabetized by the presenter’s last name, while Organized Session abstracts are alphabetized by the session chair’s last name. Note that Organized Sessions are designated in the Program Book as “Panel,” “Roundtable,” or “Workshop.” Sessions designated as “Paper Session” do not have a session abstract. To determine the time and location of an Individual Presentation, consult the index of participants at the back of the Program Book. To determine the time and location of an Organized Session, see the session number (e.g., 1A) in the Abstracts Book and consult the program in the Program Book. Individual Presentation Abstracts Pages 1 – 76 Organized Session Abstracts Pages 77 – 90 Society for Ethnomusicology 63rd Annual Meeting, 2018 Individual Presentation Abstracts Ethiopian Reggae Artists Negotiating Proximity to Repatriated Rastafari American Dreams: Porgy and Bess, Roberto Leydi, and the Birth of Italian David Aarons, University of North Carolina, Greensboro Ethnomusicology Siel Agugliaro, University of Pennsylvania Although a growing number of Ethiopians have embraced reggae music since the late 1990s, many remain cautious about being too closely connected to the This paper puts in conversation two apparently irreconcilable worlds. The first is repatriated Rastafari community in Ethiopia whose members promote themselves that of George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess (1935), a "folk opera" reminiscent of as reggae ambassadors. Since the 1960s, Rastafari from Jamaica and other black minstrelsy racial stereotypes, and indebted to the Romantic conception of countries have been migrating (‘repatriating’) to and settling in Ethiopia, believing Volk as it had been applied to the U.S. -

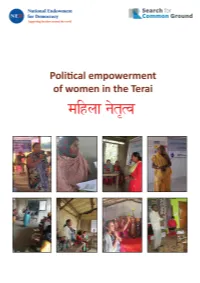

Netritwa”, Was a One-Year Pilot Project Funded by the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) Imple- Mented in Siraha District from April 2016 to March 2017

1 2 dlxnf g]t[Tj Political Empowerment of Women in the Terai Good practices to promote women’s leadership and political participation 3 dlxnf g]t[Tj Political Empowerment of Women in the Terai Editor: Pallav Ranjan Project Manager: Meena Sharma Research: Rasani Shrestha Photos: Search stock Published by Search for Common Ground. Copyright 2017. All rights reserved. The content here may not be copied, translated, stored, lent, or otherwise circulated using any forms or means (photo- copying, scanning, recording or otherwise) without the prior written consent of the copyright holder. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of Search for Common Ground or affiliated organizations. Search for Common Ground Nepal Nursery Marg, Lazimpat Kathmandu 44616, Nepal Phone: 977-1-4002010 Email: [email protected] Web: https://www.sfcg.org/Nepal Manufactured in Kathmandu ISBN: 978-9937-0-1734-3 4 Opening words A transformative program for Nepali women’s leader- ship – “Netritwa”, was a one-year pilot project funded by the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) imple- mented in Siraha district from April 2016 to March 2017. The project strengthened women’s leadership skills and their participation in political processes and engaged men in enabling women’s political participation. It contributed to create a conducive environment for women’s political par- ticipation. The project was able to empower women on their rights which led to more access for local women to govern- ment services and entitlements. In addition to having a say in the decision making process, these women are collectively raising their voices and issues through their own networks.