Netritwa”, Was a One-Year Pilot Project Funded by the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) Imple- Mented in Siraha District from April 2016 to March 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nepali Times Industry

JOYRIDE#204 9 - 15 July 2004 20 pages Rs 25 Can Deuba keep the car on the road? KUNDA DIXIT Adhikary sees it as a way to get around Maoist objections, and veryone in the new Deuba government agrees perhaps even a Eon the need to restore peace and hold elections, way to bring the they just dont agree on how to go about it. rebels to the Some want a unilateral ceasefire to pressure the negotiating table. Maoists to come to the negotiating table, others say But such a move it wont work. is sure to be opposed Peace activists have been lobbying for a ceasefire, by the army. One even if talks are not possible. They say this would close Deuba aide allow the government to address the urgent told us: Its not development and rehabilitation needs of the people. going to happen. Prime Minister Deuba has to accommodate a We dont want money to divergence of views and vested interests among the reach the Maoists. The four parties and royal nominees in his coalition. It is prime minister prefers an all- clear that on security matters, he needs the armys party presence in local bodies so that nod. One party insider told us: We have ministers the budget can be spent on development, who will all be on mobiles reporting back to their he said. bosses. Its going to be tricky. However, there are questions about The cabinets first real test is next weeks budget. whether village councils can function at a time when Already, there are signs that the UML and Deubas the Maoists have been assassinating mayors and NC-D are pulling in different directions. -

The Campaign for Justice: Press Freedom in South Asia 2013-14

THE CAMPAIGN FOR JUSTICE: PRESS FREEDOM IN SOUTH ASIA 2013-14 The Campaign for Justice PRESS FREEDOM IN SOUTH ASIA 2013-14 1 TWELFTH ANNUAL IFJ PRESS FREEDOM REPORT FOR SOUTH ASIA 2013-14 THE CAMPAIGN FOR JUSTICE: PRESS FREEDOM IN SOUTH ASIA 2013-14 CONTENTS THE CAMPAIGN FOR JUSTICE: PRESS FREEDOM IN SOUTH ASIA 2013-14 1. Foreword 3 Editor : Laxmi Murthy Special thanks to: 2. Overview 5 Adeel Raza Adnan Rehmat 3. South Asia’s Reign of Impunity 10 Angus Macdonald Bhupen Singh Geeta Seshu 4. Women in Journalism: Rights and Wrongs 14 Geetartha Pathak Jane Worthington 5. Afghanistan: Surviving the Killing Fields 20 Jennifer O’Brien Khairuzzaman Kamal Khpolwak Sapai 6. Bangladesh: Pressing for Accountability 24 Kinley Tshering Parul Sharma 7. Bhutan: Media at the Crossroads 30 Pradip Phanjoubam S.K. Pande Sabina Inderjit 8. India: Wage Board Victory amid Rising Insecurity 34 Saleem Samad Shiva Gaunle 9. The Maldives: The Downward Slide 45 Sujata Madhok Sukumar Muralidharan Sunanda Deshapriya 10. Nepal: Calm after the Storm 49 Sunil Jeyasekara Suvojit Bagchi 11. Pakistan: A Rollercoaster Year 55 Ujjwal Acharya Designed by: Impulsive Creations 12. Sri Lanka: Breakdown of Accountability 66 Images: Photographs are contributed by IFJ Affiliates. Special thanks to AP, AFP, Getty Images 13. Annexure: List of Media Rights Violations, May 2013 to April 2014 76 and The Hindu for their support in contributing images. Images are also accessed under a CreativeCommons Attribution Non-Commercial Licence. Cover Photo: Past students of the Sri Lanka College of Journalism hold a candlelight vigil at Victoria Park, Colombo, on the International Day May 2014 to End Impunity on November 23, 2013. -

Language Politics and State Policy in Nepal: a Newar Perspective

Language Politics and State Policy in Nepal: A Newar Perspective A Dissertation Submitted to the University of Tsukuba In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Public Policy Suwarn VAJRACHARYA 2014 To my mother, who taught me the value in a mother tongue and my father, who shared the virtue of empathy. ii Map-1: Original Nepal (Constituted of 12 districts) and Present Nepal iii Map-2: Nepal Mandala (Original Nepal demarcated by Mandalas) iv Map-3: Gorkha Nepal Expansion (1795-1816) v Map-4: Present Nepal by Ecological Zones (Mountain, Hill and Tarai zones) vi Map-5: Nepal by Language Families vii TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents viii List of Maps and Tables xiv Acknowledgements xv Acronyms and Abbreviations xix INTRODUCTION Research Objectives 1 Research Background 2 Research Questions 5 Research Methodology 5 Significance of the Study 6 Organization of Study 7 PART I NATIONALISM AND LANGUAGE POLITICS: VICTIMS OF HISTORY 10 CHAPTER ONE NEPAL: A REFLECTION OF UNITY IN DIVERSITY 1.1. Topography: A Unique Variety 11 1.2. Cultural Pluralism 13 1.3. Religiousness of People and the State 16 1.4. Linguistic Reality, ‘Official’ and ‘National’ Languages 17 CHAPTER TWO THE NEWAR: AN ACCOUNT OF AUTHORS & VICTIMS OF THEIR HISTORY 2.1. The Newar as Authors of their history 24 2.1.1. Definition of Nepal and Newar 25 2.1.2. Nepal Mandala and Nepal 27 Territory of Nepal Mandala 28 viii 2.1.3. The Newar as a Nation: Conglomeration of Diverse People 29 2.1.4. -

0878 2 Neetu Choudhary

Asia-Pacific Development Journal Vol. 21, No. 2, December 2014 INDO-NEPAL ECONOMIC COOPERATION: A SUBREGIONAL PERSPECTIVE Neetu Choudhary and Abhijit Ghosh* The present paper explores how a subregional engagement with bordering regions can stimulate economic cooperation among countries in the context of low levels of trade within the South Asian subregion. With special reference to shared historical legacy and culture-driven interaction — formal and informal — between Nepal and the state of Bihar in India, the paper develops a SWOT (strength, weakness, opportunity and threat) framework to rationalize and reflect on the need for a subregional perspective towards promotion of regional cooperation. With complementary applications of secondary data and field research, it shows how irrespective of formal country-level initiatives, Nepal and Bihar have engaged in successful economic partnerships and argues that those existing nodes represent the potential for greater subregional and regional economic cooperation. The paper also offers insights into formal and informal challenges and policy imperatives associated with the operationalization of the new perspective. JEL Classification: F100, F140, F150, F420. Key words: Nepal, Bihar, informal, trade, subregional perspective, economic cooperation. * Neetu Choudhary (e-mail: [email protected]) and Abhijit Ghosh (e-mail: abhijitghosh [email protected]) are assistant professors of economics in the Division of Economics, A N Sinha Institute of Social Studies, Patna, Bihar, India. This paper is based on background research conducted by the A N Sinha Institute of Social Studies, Patna in partnership with the Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi. It incorporates inputs from deliberations of the Brainstorming Workshop on Indo-Nepal Economic Cooperation, organized by the A N Sinha Institute of Social Studies, Patna on 16 July 2014. -

Evaluation of Child and Youth Participation in Peacebuilding NEPAL Release Date: June 2015

Evaluation of Child and Youth Participation in Peacebuilding NEPAL Release Date: June 2015 Authors: Primary author Bibhuti Bista, supporting author Claire O’Kane Publisher: Global Partnership for Children and Youth in Peacebuilding Contact: www.GPCYP.com, [email protected] Evaluation of Child and Youth Participation in Peacebuilding – Nepal Acknowledgements The 3M evaluation has supported partnerships and participatory processes at every level from local to global. We would like to appreciate the commitment and efforts of significant numbers of individuals and agencies who have been part of this journey to better understand, evaluate, and increase support for child and youth peacebuilding. First and foremost we appreciate the commitment, motivation and insights of child and youth peacebuilders and adult supporters who dedicated their time and energy as Local Evaluation Team members. The rich findings, analysis and evidence base shared in this report are the results of hard work and dedication of LET members. Immense thanks to Nepal LET members: Aaitaram, Ajay, Akwar, Amrendra, Anup, Bhawana, Deepak, Durga, Ganesh, Jamuna, Jay, Kamni, Karna, Keshari, Krishna, Laxmi, Mahendra, Akhtar, Meena, Mintu, Narayan, Nirmala, Omprakash, Pratima, Puja, Sabita, Santosh, Saru, Shova, Sirjana, Suhani, Sunil, Surendra, Yogmaya, Tej, Bisna, Bimala and Indu. Particular thanks to LET Coordinators who shared information, coordinated planning, transcribed findings, and followed up to gather additional sources of evidence. Thanks and appreciation to Deepak Sharma, Hem Raj Joshi, Satyendra Kumar Yadav and Sher Bahadur Thapa. We also extend our thanks and gratitude to colleagues in the youth organizations (JCYCN, Nawalparasi; YNPD-Mahottari) and NGO partners (Bikas Ka Lagi Pailaharu Nepal, Rolpa; Community Development Center, Doti) who provided important support to the LETs. -

Nepali Nepal Bhasha

h.. 1 S: Newah Vijiiana (The Journal of Newar Studies) Editorial ISSN 1536-8661 1125 Numberd 2004-05 One can sec that Newah VijiiLina has evolved wit11 time. It has seen much rnctarnorphosis since its first issue back in 1997 not only in the Publisher issues the~nselveshut also the entire Newah cornmunity. The Newah International Nepill BhashZ community has been impacted hy the demise of Inany great Newah Sev3 Samiti (INBSS) scholars and personals. We would like to extend our c~~ndolenccsto Center For Nepale.\e Language Bhikshu Sudarshan. lswarananda Shrethacharya. Revati Ra~n:~nananda. & Culture Sahu Jyana Jyoti Kansakar, Pror. Rernhard Kolver and Bert van den Portland, Oregon USA Hoek. We are very grateful for their c~~ntrihutionsto the Newah c~~rnmunity. Another type of metamorphoses is seen in the creation of a worldwide community with the advent bo~~mof the internet. Due to accesses of international exchanges of information in sophisticated way through the internet, the popularity of Newah Vijiiina is growing rapidly. Recently. last summer, a Nepal Bhasa web magazine, Editor nvw~v.ne~r.a~~osr.corn.~~p~was launched by dedicated Newah people Day3 R. Shakya whose voluntary work has lead to uploading of inforniation pertaining to the Newah Vijaana journal. We highly reci)mrnend you to please Assistant Editor visit the wehsite and click on the Ncw3h VijiiZna section to ohtain Sudip R. Shakya inform;rtion on previous issues of this journal. Of the rn.rny other websites that promotes the Newah heritage. ~rtviv.~~~.ajn.rrlu~~~l.rorn Advisor deserves a mention. The wehsite contains a froup mailing and Prof. -

Indigenous and Local Climate Change Adaptation Practices in Nepal

CASE STUDY: 2 Government of Nepal Ministry of Science, Technology and Environment Pilot Program for Climate Resilience Mainstreaming Climate Change Risk Management in Development ADB TA 7984: Indigenous Research INDIGENOUS AND LOCAL CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION PRACTICES IN NEPAL CASE STUDY CHAPTERS Introduction, objectives and methodology CASE STUDY I Understanding indigenous and local practices in water CASE STUDY II management for climate change adaptation in Nepal Understanding indigenous and local practices in forest and CASE STUDY III pasture management for climate change adaptation in Nepal Understanding indigenous and local practices in rural CASE STUDY IV transport infrastructure for climate change adaptation in Nepal Understanding indigenous and local practices in CASE STUDY V settlements and housing for climate change adaptation in Nepal Understanding indigenous and traditional social CASE STUDY VI institutions for climate change adaptation in Nepal ACRONYMS CASE STUDY ACAP Annapurna Conservation Area Programme ADB Asian Development Bank AGM Annual General Assembly AIPP Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact AIS Argali Irrigation System AMIS Agency Managed Irrigation System BLGIP Bhairawa Lumbini Ground Water Irrigation Project BLGWP Bhairahawa Lumbini Ground Water Project BTCB Baglung Type Chain Bridges BZMC Buffer Zone Management Council BZUG Buffer Zone User Groups CAPA Community Adaptation Programme of Action CBFM Community Based Forest Management CBNRM Community Based Natural Resource Management CBOs Community Based Organisations CBS -

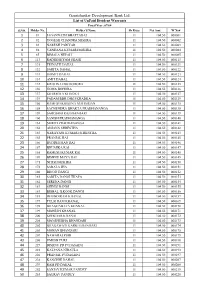

Gaurishankar 2067 68

Gaurishankar Development Bank Ltd. List of UnPaid Divident Warrants Fiscal Year :67/68 S.NO. Holder No. Holder'S Name Sh Kitta Net Amt W No# 1 81 JAGANNATH BHATTARAI 11 104.50 000081 2 82 YOGESH CHANDRA MISHRA 11 104.50 000082 3 83 NARESH PARIYAR 11 104.50 000083 4 84 VANDANA KUMARI MISHRA 11 104.50 000084 5 85 BIMALA NEPALI 11 104.50 000085 6 113 RADHESHYAM SHAHI 11 104.50 000113 7 131 TEJNATH DAHAL 11 104.50 000121 8 132 SARITA DAHAL 11 104.50 000122 9 133 ISHMIT DAHAL 11 104.50 000123 10 134 AMIT DAHAL 11 104.50 000124 11 135 KRISHNA DOJ BOHORA 11 104.50 000125 12 136 GOMA BOHORA 11 104.50 000126 13 137 SHARMILA KHADKA 11 104.50 000127 14 139 PADAM BDR DHOJ KHADKA 11 104.50 000129 15 150 RAMESH KRISHNA MAHARJAN 11 104.50 000135 16 158 SACHENDRA BHAKTA PRADHANANGA 11 104.50 000138 17 159 SAROJANI RAJBHANDARI 11 104.50 000139 18 160 SANISH PRADHANANGA 11 104.50 000140 19 161 SMRITI PRADHANANGA 11 104.50 000141 20 162 ANJANA SHRESTHA 11 104.50 000142 21 163 NARAYANI KUMARI SHRESTHA 11 104.50 000143 22 165 PRANJAL RAI 11 104.50 000145 23 166 BUDDHI MAN RAI 11 104.50 000146 24 167 BHUMIKA RAI 11 104.50 000147 25 168 RAMESH KUMAR RAI 11 104.50 000148 26 169 BISHNU MAYA RAI 11 104.50 000149 27 171 NITISH MISHRA 11 104.50 000150 28 172 SARALA JHA 11 104.50 000151 29 180 BINOD DANGI 11 104.50 000152 30 181 SARITA DANGI THAPA 11 104.50 000153 31 182 SERENA DANGI 11 104.50 000154 32 183 SHINBI DANGI 11 104.50 000155 33 184 BISHAL ILKOOK DANGI 11 104.50 000156 34 185 DHUNDIRAM KHANAL 11 104.50 000157 35 197 TULSI RAM KHANAL 11 104.50 000169 36 -

A House Divided: Land, Kinship, and Bureaucracy in Post-Earthquake Kathmandu

A House Divided: Land, Kinship, and Bureaucracy in Post-Earthquake Kathmandu by Andrew Haxby A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in The University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Professor Tom Fricke, Chair Associate Professor Lan Deng Assistant Professor Jatin Dua Associate Professor Matthew Hull Professor Stuart Kirsch Andrew Warren Haxby [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0002-5735-1173 © Andrew Warren Haxby 2019 Acknowledgements It is utterly humbling to think of all the people and institutions who have helped make this document and research project possible. This project received generous funding from multiple agencies at different stages. I want to thank the University of Michigan’s Rackham graduate school, which funded both my pre-dissertation fieldwork and a significant portion of my main fieldwork, as well as provided me with funding throughout my graduate career. I also want to thank the National Science Foundation and the Wenner Gren Foundation for their generous support of my fieldwork as well. Finally, thank you to the U.S. Department of Education’s Foreign Language and Area Studies program for their support of my language training. I also want to extend my thanks to the Nepali government for hosting me during my fieldwork, and to Tribhuvan University for sponsoring my research visa, particularly to the Economics department and Prof. Kusum Shakya. Throughout this process, both the Nepali government and Tribhuvan University have been committed in supporting my research agenda, for which I am deeply grateful. I also want to thank both the commercial bank and finance company that allowed me to observe their work. -

KVEO Front Matters Jan 16.Qxp

Annexes 120 Kathmandu Valley Environment Outlook Annexes Annex 1 Annual Average Extreme Temperatures for 1985, 1999, and 2004 Annual average extreme temperatures for 1985, 1999, and 2004 1985 1999 2004* Month Max Min Max Min Max Min January 18.1 2.4 21.0 1.0 18.2 3.1 February 20.1 3.7 26.0 6.0 22.0 5.2 March 26.3 9.0 28.0 8.0 27.3 10.7 April 28.6 12.1 33.0 14.0 27.7 13.2 May 28.0 15.5 29.0 17.0 28.6 16.5 June 28.9 19.2 29.0 19.0 28.8 16.9 July 27.1 19.6 28.0 20.0 27.7 20.2 August 28.8 20.2 28.0 20.0 29.0 20.6 September 26.7 18.3 29.0 19.0 28.1 19.3 October 24.4 13.7 26.0 14.0 26.0 13.1 November 22.2 7.0 24.0 8.0 22.7 7.5 December 19.3 4.8 21.0 5.0 20.6 4.5 Source: Handbook of Environment Statistics, Nepal - 2002; * Statistical Year book 2005 Annexes 121 Annex 2 The Seven World Heritage Sites of Kathmandu Valley 1. Kathmandu Durbar Square Kathmandu Durbar Square was built in 613 A.D. (B.S. 670) by the Lichchavi dynasty. During the reign of King Pratap Malla, a statue of Hanuman was installed at the entrance (dhoka) of the palace (1672 A.D.– B.S. -

Halwai People of Nepal by Kara Strange

Halwai People of Nepal By Kara Strange https://joshuaproject.net/people_groups/16905/NP Introduction/History The Halwai people group, also known as the Palma Halwais or Rajkarnikar, are part of a Newar clan and were the original inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley in Nepal. They are an unreached and unengaged group, with about 81,000 people. The traditional occupation of the Halwai people is making candy and sweets, known as "mithai." 1 The Halwai people are typically well respected socially because of their services to the community and the ritualistic importance of these actions. The Halwai play a key role in celebrations such as marriages and childbirths because of the importance that sweets have for these festivals.2 1 “Rajkarnikar.” Wikipedia. August 30, 2014. Accessed March 1, 2017. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rajkarmikar. 2 Russell, Robert V. The tribes and castes of the central provinces of India, volume III of IV. Vol. III. United States: The library of Alexandria. Accessed February 28, 2107. The primary language of the Halwai people group in Nepal is Maithili. If they can read Nepali or Hindi they can usually also read Maithili. 3 Where are they located? The Halwai people are located in parts of southern Nepal as well as the Kathmandu Valley and its surrounding cities, Patan and Bhaktapur. Kathmandu, the capital of Nepal, is the largest city in Nepal and provides many resources for the Halwai people. It is home to several major pilgrimage sites for some of the world's religions, such as Hinduism and Buddhism.4 A large number of Halwai also live in India. -

Econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Rajkarnikar, Pushpa Raj Working Paper The Need for and Cost of Selected Trade Facilitation Measure Relevant to the WTO Trade Facilitation Negotiations: A Case Study of Nepal ARTNeT Working Paper Series, No. 8 Provided in Cooperation with: Asia-Pacific Research and Training Network on Trade (ARTNeT), Bangkok Suggested Citation: Rajkarnikar, Pushpa Raj (2006) : The Need for and Cost of Selected Trade Facilitation Measure Relevant to the WTO Trade Facilitation Negotiations: A Case Study of Nepal, ARTNeT Working Paper Series, No. 8, Asia-Pacific Research and Training Network on Trade (ARTNeT), Bangkok This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/178366 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence.