Filmmaking Theory for Vertical Video Production

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Screen Genealogies Screen Genealogies Mediamatters

media Screen Genealogies matters From Optical Device to Environmental Medium edited by craig buckley, Amsterdam University rüdiger campe, Press francesco casetti Screen Genealogies MediaMatters MediaMatters is an international book series published by Amsterdam University Press on current debates about media technology and its extended practices (cultural, social, political, spatial, aesthetic, artistic). The series focuses on critical analysis and theory, exploring the entanglements of materiality and performativity in ‘old’ and ‘new’ media and seeks contributions that engage with today’s (digital) media culture. For more information about the series see: www.aup.nl Screen Genealogies From Optical Device to Environmental Medium Edited by Craig Buckley, Rüdiger Campe, and Francesco Casetti Amsterdam University Press The publication of this book is made possible by award from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and from Yale University’s Frederick W. Hilles Fund. Cover illustration: Thomas Wilfred, Opus 161 (1966). Digital still image of an analog time- based Lumia work. Photo: Rebecca Vera-Martinez. Carol and Eugene Epstein Collection. Cover design: Suzan Beijer Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 900 0 e-isbn 978 90 4854 395 3 doi 10.5117/9789463729000 nur 670 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) All authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2019 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustrations reproduced in this book. -

Digital Digest March 26, 2020, R&R Partners

1 The Digital Digest March 26, 2020, R&R Partners Introduction We don’t need to download an app or wear a headset to experience the COVID-19 altered reality. Our daily lives and routines changed overnight, completely shifting how, when and where we consume media. TV is the shining star again as Americans are glued to their screens, waiting for the latest news between bingeing on shows. Digital is surging between telecommuting and scrolling through social feeds to feel less isolated during a time of social distancing. Below reveals how channel consumption has modified since coronavirus entered our lives like a wrecking ball. Your marketing efforts should reflect these paramount shifts. COVID-19’s Impact on Media Consumption by Channel Data is being updated by the day and still not released by some platforms, but this is what we know so far: • TV: Traditional TV is center stage again. Nielsen estimates TV usage to rise nearly 60%. • CTV/OTT: Nielsen also found an average 61% increase in streaming video via the TV. Top apps used are Netflix, Amazon Prime and Hulu. Disney Plus is on the rise thanks to the early release of Frozen 2. • Digital: Everyone is spending more time online, both on desktop and mobile. Laptop/desktop usage increased by 40% and mobile increased by 53.3%* week over week. • Social Media: Social distancing grows social media with 46% increase* week over week. • Audio: A Nielson perceptual study from earlier this week reports that 83% of U.S. adults have continued or increased their radio consumption due to COVID-19, and Spotify and Pandora are seeing global streams rise. -

How Can We Help MX Player Grow and Increase Its Retention? Aditya Gopal Ganguly

How can we help MX Player grow and increase its retention? Aditya Gopal Ganguly MX Player: A Snapshot MX Player, originally one of the oldest and most popular video players for locally-stored media in the market, was acquired by Times Internet for $140~$200 million in 2018. Post-acquisition, Times Internet has added features like video streaming of original content, partner content, live channels, movies bundled with music, games and news. The OTT feature rolled out initially in the Indian market has been expanded to more than half a dozen markets like the U.S and U.K. The company is also targeting the Middle East and South Asia. The app caters to users across the tiers in India. The entire streaming platform follows Advertising Video on Demand (AVOD) model and has not only carved a space for itself being a free OTT service among a plethora of paid ones but has also managed to top the category over the past few months. Key metrics ● 1,50,000 hrs of premium video content, audio music and games, all for free. ● Largest market - India (175 MAUs, 75 DAUs), Globally - (280 MAUs) ● App Annie’s Breakout Video Streaming App of 2019 (India), ahead of Hotstar, Netflix, Amazon Prime Video and Reliance owned Jio TV. Also among top 10 publishers in India and incredible growth in Indonesia. What has worked? ● Investment in original content has paid off for the organization. MX Player plans to have 50 originals on its platform this year. ● Web Series are the most consumed form of content followed by linear, traditional TV followed by movies. -

SHOOT Digital PDF Version, August/Sept 2016, Volume 57

www.SHOOTonline.com August/September 2016 Chat Room: John Leverence 6 VR & AR 18 DGA of Wise/courtesy Howard by Photo (From top left clockwise) DP James Hawkinson (l) and actress Alexa Davalos in The Man In The High Castle (photo courtesy of Amazon); Actor Jonathan Pryce (l) and director Jack Bender on location for Game of Thrones (photo courtesy of HBO); Claire Danes in Homeland (photo by Stephan Rabold/courtesy of Showtime). Top Ten Tracks 22 The Road To Emmy Part 14 Insights Into Game of Thrones, Homeland, The Night Manager, The Man In The High Castle, Black Sails 4 4 2016 Mid-Year Industry Report Card 8 (L-r) Andy Clarke of Publicis NY; Stacy McClain of Camp + King; Dave Damman of Grupo Gallegos; and Libby Brockhoff of Odysseus Arms Visual Effects & Animation Top Ten Chart 24 The world’s fastest video editing and color correction software! Now with over 1,000 enhancements and 250 new features, DaVinci New Effects Resolve 12.5 gives editors and colorists a faster, more refined editing DaVinci Resolve 12.5 introduces ResolveFX, an amazing collection of and grading experience than ever! You get professional editing with high performance plug-ins such as blurs, light rays, mosaics, and more! advanced color correction, plus incredible new effects so you can edit, You also get more transitions, enhanced titles, keyframe animation and color correct, add effects and deliver projects from start to finish, all in speed ramp effects, along with Fusion Connect, which lets you send one single software tool! shots to Fusion for visual effects! Faster Editing DaVinci Resolve 12.5 Studio DaVinci Resolve 12.5 features dozens of new editing and trimming tools, When you need to work at resolutions higher than Ultra HD, like DCI 4K along with faster timeline performance! You get new ripple overwrite, or even on stereoscopic 3D projects, then upgrade to DaVinci Resolve paste insert, revolutionary new audio waveform overlays that help you 12.5 Studio. -

Maximize Your Company's Presence & Leads with Instagram & IGTV

Ma Maximize Your Company's Presence & Leads With Instagram & IGTV Marki Lemons Ryhal MARKI LEMONS RYHAL Secrets of Top Selling Agents | Marki Lemons-Ryhal Maximize Your Company's Presence & Leads With Instagram & IGTV An estimated 71% of US businesses use Instagram to reach its 1 billion+ monthly active users. IGTV is a new app designed for watching long-form, full-screen vertical videos, and Instagram Stories are another avenue to reach potential clients. Instagram works especially well when paired with Facebook, as pictures shared to Facebook from Instagram receive 23% more engagement than images published directly on Facebook itself. In this session you’ll learn out how get real results on Instagram by: • Producing photos and video with Canva, Quik, and Legend • Setting up your Instagram business account • Generating and cross-promoting Instagram Stories • Automating your Instagram content to share on Twitter, Tumblr, Flickr, Pinterest and Facebook • Selecting and utilizing hashtags to increase engagement • Creating an IGTV Channel and uploading a vertical video. 2 Instagram Stories 3 IGTV FOLLOW @markilemons 1 Feed Post A search under “People/Accounts” for the term “Promotional Products” yields Did you know that the “Name” field in your Instagram bio is searchable? ➔ 1: IGTV Five Ways Think YouTube, but on Instagram - except videos won’t show up in Google search results. to Generate ➔ 2&3: Instagram Stories & Instagram Live a Lead on ➔ 4: Blog-Like Post Give people a reason to care. ➔ 5: Carousel Posts Instagram An album of photos or videos included as one post - “swipe left.” Secrets of Top Selling Agents | Marki Lemons-Ryhal 2 Instagram Stories 3 IGTV FOLLOW @markilemons 1 Feed Post 2 Instagram Stories 1 2 3 You can watch IGTV videos in the Instagram app, in the standalone IGTV app, or by clicking the IGTV button on someone’s Instagram profile. -

VERTICAL VIDEO and BEYOND What Vertical Video Is, How to Use It, and Why It Needs to Evolve to Support Today’S Mobile Consumer

eBOOK VERTICAL VIDEO AND BEYOND What vertical video is, how to use it, and why it needs to evolve to support today’s mobile consumer. CONTENTS What you will learn in this marketing guide CHAPTER 1 Rising customer expectations demand dynamic video experiences CHAPTER 2 Vertical video: What it is and why it matters CHAPTER 3 What’s at stake: The experience gap that’s harming your mobile marketing CHAPTER 4 Key considerations for vertical video CHAPTER 5 Enhancing marketing performance with responsive orientation for ads CHAPTER 6 How it gets done: Responsive orientation in practice CHAPTER 7 Results of taking a responsive approach to ad orientation CONCLUSION VERTICAL VIDEO AND BEYOND | TABLE OF CONTENTS Rising customer expectations demand CHAPTER 1 dynamic video experiences Mobile is undeniably the most direct, personal settle for catfish.” This holds true for mobile and ubiquitous digital connection point to as well. Once consumers have had a perfect consumers. While desktops and laptops mobile experience, it’s difficult to tolerate reigned supreme for many years, mobile anything else. now represents almost two out of three digital media minutes spent by consumers, As mobile ad spending in the U.S. alone balloons with mobile apps dominating 60 percent of to over $50 billion in 2017, consumers will that time and representing 80 percent of the expect—even demand—that ad experiences growth overall since 2013. align with their “caviar” tastes. Those companies that don’t deliver high-quality With the continued shift to mobile-first ads will, at best, see performance suffer everything came an unmistakable shift in and, at worst, be exposed to many unsafe consumer expectations around what mobile brand experiences. -

15% Gen Z, 20% Gen Y, 11% Gen X

THE TRENDERA FILES Trendera THE NEW MEDIA ISSUE Volume 9, Issue 3, September 2018 NBCUniversal THE TRENDERA FILES: THE NEW MEDIA ISSUE CONTENTS INTRO 4 CONTENT OVERLOAD 39 40 Short Form Content 41 Long Form Content 42 Gaming MACRO TRENDS 43 Music 7 44 Internet Culture 8 Hype Machine 45 New Media: Who’s Doing It Right 12 Gaming the System 16 Why So Serious? NOW TRENDING 48 BY THE NUMBERS 49 Entertainment 20 51 Lifestyle 21 Methodology 54 Fashion / Retail / Shopping 22 Streaming & Mobile Reign TrenderaSupreme 57 Digital / Technology 26 TV Personalities & Shows 28 Entertainment Behaviors 30 Online Videos 32 Movies STANDOUT MARKETING 60 33 Gaming 35 Social Media 37 Putting It All Together NBCUniversal2 TABLE OF CONTENTS WHAT’S HOT 65 66 Gen Z Kids 68 Gen Z 13+ 70 Millennials 72 Who’s Hot 76 Digital Download KNOW THE SLANG 78 STATISTICS: GEN X, YTrendera & Z 81 NBCUniversal3 THE TRENDERA FILES: THE NEW MEDIA ISSUE You heard it here first: the golden age of entertainment is officially over. However, before the alarm bells start ringing, let us clarify: we are no longer in the golden age of entertainment because today, entertainment is everything. We live in an attention economy where viewership, clicks, and likes control influence, relevance, and the bottom line. Consequently, every experience, product, and piece of content is being created with the entertainment factor in mind—from news stories and video tutorials to influencer personas and bathrooms (yes, bathrooms). All of this sounds good in theory—after all, who doesn’t love to be entertained?! But for marketers and content creators, it means that creating compelling media has gotten that much harder. -

2018 IAB Video Landscape Report

Video Landscape Report IAB Digital Video Center of Excellence May 2018, 4th Edition Table of Contents Introduction 3 Background 4 Executive Summary 5 Landscape 7 Growth Opportunities 18 Challenges & Solutions 35 Emerging Trends 46 IAB Call to Action 49 IAB Resources 50 Closing Thoughts 51 2 Introduction In early 2018 at the IAB Annual Leadership Meeting, IAB announced a paradigm-shifting thesis to capture, explain and understand an “enduring shift in the way the consumer economy operates”, a shift from a century old “indirect brand economy” to a “direct brand economy” characterized by data-driven, digitally native, and customer experience-obsessed upstart brands with direct connections to consumers. They are disrupting the legacy business model of marketing and driving the growth of a new consumer economy. All digital publishers, media companies, technology and data solution providers in the ecosystem have an important role to play in building the “attention stack” that both direct and indirect brands can leverage to scale their growth and/or empower their digital transformation. Video, with the on-going convergence between traditional TV and digital video, has become an integral and powerful part of this attention stack for all 21st century brands in the new direct brand economy. However, the constant change and confluence of technological innovations and consumer behavior shifts also cast new questions around video - What does video mean? What will it become? How is video used to reach, engage, and drive attention and action? It is absolutely imperative to understand the complex and evolving ecosystem of video advertising to guide both buy-side and sell-side perspectives and decisioning. -

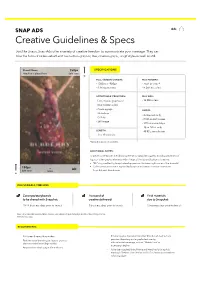

Creative Guidelines & Specs

SNAP ADS Ads Creative Guidelines & Specs Just like Snaps, Snap Ads offer a variety of creative freedom to communicate your message. They can take the form of video—whether it be motion graphic, live, cinema-graph, or gif style—as well as still. SPECIFICATIONS - Brand Name 150px Headline is placed here Safe zone FULL SCREEN CANVAS: FILE FORMAT: - 1080px x 1920px - .mp4 or .mov * - 9:16 aspect ratio - H.264 encoded ACCEPTABLE CREATIVES: FILE SIZE: - Live, motion graphic, or - 32 MB or less stop motion video - Cinemagraph AUDIO: - Slideshow - 2 channels only - Gif-like - PCM or AAC codec - Still Image - 192 minimum kbps - 16 or 24 bit only LENGTH: - 48 KHz sample rate - 3 to 10 seconds *Jpegs & pngs are not accepted. ADDITIONAL NOTES: To prevent overlap with the following elements, Snapchat suggests avoiding placement of logos or other graphic elements within 150px of the top and bottom of creative. • “AD” slug is added by Snapchat and appears on the lower right corner of the Snap Ad 150px • Call-to-action and caret is applied by Snapchat to bottom center of creative for - AD Safe zone MORE Snap Ads with Attachments DELIVERABLE TIMELINE Concepts/storyboards 1st round of Final materials to be shared with Snapchat: creative delivered: due to Snapchat: 10-14 business days prior to launch 5 business days prior to launch 3 business days prior to launch Note: Any materials received after creative due dates will put campaign at risk of launching on time. API timelines vary. REQUIREMENTS - Full screen & vertically formatted - If featuring your Sponsored Creative Tool, the ad must include persistent branding and a graphic text overlay - Features visual branding (i.e. -

Purpose & Goodness

PURPOSE & GOODNESS MARC PRITCHARD, THE ANA’S NEW CHAIRMAN, WANTS TO CHANGE THE WORLD SPECIAL SECTION: ON THE FUTURE OF VIDEO ADVERTISING IS SPEC WORK WORTH IT? DECEMBER 2016 COVER/COURTESY OF P&G; THIS PAGE/SHUTTERSTOCK.COM Leadership and Marketing Excellence CONTENTS DECEMBER 2016 Board of Directors Get the latest from all of the ANA’s ROGER ADAMS, USAA publications in ANA Newsstand. PAUL ALEXANDER, EASTERN BANK Leave comments, watch video, share DANA ANDERSON, MONDELEZ INTERNATIONAL online, and more. ana.net/newsstand MARYAM BANIKARIM, HYATT HOTELS LINDA BOFF, GENERAL ELECTRIC CHRIS BRANDT, BLOOMIN’ BRANDS ROB CASE, NESTLÉ 03 GAURAV CHAND, DELL DAVID CHRISTOPHER, AT&T CHRIS CURTIN, VISA SUZY DEERING, EBAY DEANIE ELSNER, KELLOGG SANJAY GUPTA, ALLSTATE JACK HABER, FORMERLY OF COLGATE-PALMOLIVE JON IWATA, IBM BRADLEY JAKEMAN, PEPSICO GERALD JOHNSON II, AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION JEFFREY JONES II, UBER MAGGIE CHAN JONES, SAP AMERICA DENISE KARKOS, TD AMERITRADE 14 JOHN KENNEDY JR., CONDUENT RICH LEHRFELD, AMERICAN EXPRESS KRISTIN LEMKAU, JPMORGAN CHASE CHANTEL LENARD, FORD PAGE ALISON LEWIS, JOHNSON & JOHNSON #ANALOG BOB LIODICE, ANA 02 The big change coming to ANA magazine; T-Mobile’s drive to ROB MASTER, UNILEVER NADINE McHUGH, L’ORÉAL connect cars to the IoT; a picture-perfect change on Instagram; SUSAN POPPER, HEWLETT PACKARD ENTERPRISE upcoming events; key stats; quick facts; and more. MARC PRITCHARD, PROCTER & GAMBLE RAJA RAJAMANNAR, MASTERCARD TONY ROGERS, WALMART PAGE A FORCE FOR GOOD DIEGO SCOTTI, VERIZON 04 New ANA Chairman Marc Pritchard has used P&G’s marketing JAMES SPEROS, FIDELITY INVESTMENTS MEGAN STOOKE, GENERAL MOTORS to talk about social issues and make a difference in the world — his MARC STRACHAN, DIAGEO plans for the industry are no different. -

Music Marketing for the Digital Era Issue 234 Coverfeature

05-06 Tools Hive 07-08 Campaigns Ed Sheeran, Above & Beyond, Chance The Rapper, Slipknot 09–13 Behind The Campaign- AVICII AUGUST 07 2019 sandboxMUSIC MARKETING FOR THE DIGITAL ERA ISSUE 234 COVERFEATURE M2V THE NEW ERA OF MUSIC VIDEOS It is a sign of the increasingly visual world in which we Net’ benefits: Thom Yorke – Anima / live that most artists wouldn’t consider releasing a song Kid Cudi – Entergalactic these days without some sort of visual accompaniment, 1)When Anima, Thom Yorke’s third solo at the start of 2019) and a certain prestige be it the humble pack shot video or a budget-stretching album, arrived out of the blue at the end of that you don’t get with slinging your video June 2019, accompanied by a 12-minute onto YouTube alongside hand-made ‘Baby VR effort. At the same time, there are now more places Netflix film, it inspired a fair amount of Shark’ clips. than ever to watch music videos, with the recent arrival jealousy in the music industry. Not only The following month it was announced of Thom Yorke’s Anima video on Netflix serving as a does Netflix typically offer cold, hard cash that Kid Cudi’s new album, Entergalactic, reminder that, even today, there are still new territories upfront for video content (we don’t know for would also have a Netflix presence. The for the music video to explore and conquer. With this sure that this was the case with Anima, as rapper has teamed up with Kenya Bariss, Yorke’s management would not comment the creator of TV show Black-ish, to create in mind, sandbox brings you its guide to M2V: The New on the deal terms – but it seems extremely an animated Netflix series, also called Era Of Music Videos. -

Digital Trends to Watch in 2019

Digital Trends to Watch in 2019 January 2019 As we close out the “teens” decade and prepare for TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE the Roaring Twenties, the media landscape remains as complicated as ever. That cat-and-mouse game 1 VERTICAL VIDEO WILL EXPLODE 3 between marketers (who seek to sell their wares to consumers) and consumers (who seek to limit or 2 AMAZON BECOMES A ONE-STOP SHOP, LITERALLY 4 control the marketing messages they receive) has elevated to new levels. It is so easy to be 3 PROGRAMMATIC CONTINUES TO EVOLVE 5 overwhelmed by everything new that comes our way. We seek to separate the shiny objects from 4 IDENTITY MARKETING BECOMES TABLE STAKES 6 the trends that will make a real difference in how consumers and marketers interact in the coming 5 PODCASTS WILL BECOME ADDRESSABLE & SCALABLE 8 years. With that in mind, we present Harmelin Media’s Digital Trends to Watch in 2019 – seven 6 THE IMPACT OF GDPR ON DATA SECURITY & PRIVACY 10 developments that you should pay attention to now, or risk playing catch-up down the road. 7 THE ERA OF VOICE 12 2 Vertical video ads, which were first seen on mobile-only Snapchat Stories in 2014, have now made their way to all the major social and digital platforms including Facebook Stories 1 and Newsfeed, Instagram Stories, Pinterest, YouTube, and Spotify. Vertical video presents advertisers with the opportunity to have more control over onscreen real estate. Advertisers can now deliver ads at scale that appear native on the platforms and devices on which they are viewed.