Visions of 1968: Radical Aesthetics in Porcile, WR and Tout Va Bien

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum Rivette: Texts and Interviews (editor, 1977) Orson Welles: A Critical View, by André Bazin (editor and translator, 1978) Moving Places: A Life in the Movies (1980) Film: The Front Line 1983 (1983) Midnight Movies (with J. Hoberman, 1983) Greed (1991) This Is Orson Welles, by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (editor, 1992) Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995) Movies as Politics (1997) Another Kind of Independence: Joe Dante and the Roger Corman Class of 1970 (coedited with Bill Krohn, 1999) Dead Man (2000) Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000) Abbas Kiarostami (with Mehrmax Saeed-Vafa, 2003) Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (coedited with Adrian Martin, 2003) Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) Discovering Orson Welles (2007) The Unquiet American: Trangressive Comedies from the U.S. (2009) Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Film Culture in Transition Jonathan Rosenbaum the university of chicago press | chicago and london Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote for many periodicals (including the Village Voice, Sight and Sound, Film Quarterly, and Film Comment) before becoming principal fi lm critic for the Chicago Reader in 1987. Since his retirement from that position in March 2008, he has maintained his own Web site and continued to write for both print and online publications. His many books include four major collections of essays: Placing Movies (California 1995), Movies as Politics (California 1997), Movie Wars (a cappella 2000), and Essential Cinema (Johns Hopkins 2004). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

Beyond the Black Box: the Lettrist Cinema of Disjunction

Beyond the Black Box: The Lettrist Cinema of Disjunction ANDREW V. UROSKIE I was not, in my youth, particularly affected by cine - ma’s “Europeans” . perhaps because I, early on, developed an aversion to Surrealism—finding it an altogether inadequate (highly symbolic) envision - ment of dreaming. What did rivet my attention (and must be particularly distinguished) was Jean- Isidore Isou’s Treatise : as a creative polemic it has no peer in the history of cinema. —Stan Brakhage 1 As Caroline Jones has demonstrated, midcentury aesthetics was dominated by a rhetoric of isolated and purified opticality. 2 But another aesthetics, one dramatically opposed to it, was in motion at the time. Operating at a subterranean level, it began, as early as 1951, to articulate a vision of intermedia assemblage. Rather than cohering into the synaesthetic unity of the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk , works in this vein sought to juxtapose multiple registers of sensory experience—the spatial and the temporal, the textual and the imagistic—into pieces that were intentionally disjunc - tive and lacking in unity. Within them, we can already observe questions that would come to haunt the topos of avant-garde film and performance in the coming decades: questions regarding the nature and specificity of cinema, its place within artistic modernism and mass culture, the institutions through which it is presented, and the possible modes of its spectatorial engagement. Crucially associated with 1. “Inspirations,” in The Essential Brakhage , ed. Bruce McPherson (New York: McPherson & Co., 2001), pp. 208 –9. Mentioned briefly across his various writings, Isou’s Treatise was the subject of a 1993 letter from Brakhage to Frédérique Devaux on the occasion of her research for Traité de bave et d’eternite de Isidore Isou (Paris: Editions Yellow Now, 1994). -

Letterism 1947-2014 Vol. 1

The Future is Unwritten: Letterism 1947-2014 Vol. 1 Catalog 17 Division Leap 6635 N. Baltimore Ave. Ste. 111 Portland, OR 97203 www.divisionleap.com [email protected] 503 206 7291 “Radically anticipating Herbert Marcuse, Paul Goodman, and their Letterism is a movement whose influence is as widespread as it is unacknowledged. From punk to concrete poetry to experimental film, from the development of youth culture to the student uprisings of 1968 and epigones in the 1960s new left, Isou the formation of the Situationist International, most postwar avant-garde movements owe a debt to it’s rev- produced an analysis of youth as olutionary theories, yet it remains largely overlooked in studies of the period (some notable exceptions are listed in the bibliography that follows the text). an inevitably revolutionary social sector - revolutionary on its own This catalog contains over one hundred items devoted to Letterism and Inismo. To the best of our knowl- edge it is the first devoted to either of these movements in the US. It contains a number of publications terms, which meant that the terms which have little or no institutional representation on these shores, and represents a valuable opportunity for of revolution had to be seen in a future research. new way.” A number of the items in this catalog were collected by the anarchist scholar Pietro Ferrua, who was closely associated with members of both Letterism and Inismo and who has written a great deal about both move- ments. Ferrua organized the first international conference on Letterism here in Portland in 1979 [see #62]. -

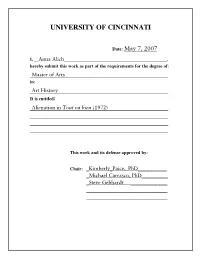

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 7, 2007 I, __Anna Alich_____________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: Art History It is entitled: Alienation in Tout va bien (1972) This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _Kimberly_Paice, PhD___________ _Michael Carrasco, PhD__________ _Steve Gebhardt ______________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Alienation in Jean-Luc Godard’s Tout Va Bien (1972) A thesis presented to the Art History Faculty of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning University of Cincinnati in candidacy for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Anna Alich May 2007 Advisor: Dr. Kimberly Paice Abstract Jean-Luc Godard’s (b. 1930) Tout va bien (1972) cannot be considered a successful political film because of its alienated methods of film production. In chapter one I examine the first part of Godard’s film career (1952-1967) the Nouvelle Vague years. Influenced by the events of May 1968, Godard at the end of this period renounced his films as bourgeois only to announce a new method of making films that would reflect the au courant French Maoist politics. In chapter two I discuss Godard and the Dziga Vertov Group’s last film Tout va bien. This film displays a marked difference in style from Godard’s earlier films, yet does not display a clear understanding of how to make a political film of this measure without alienating the audience. In contrast to this film, I contrast Guy Debord’s (1931-1994) contemporaneous film The Society of the Spectacle (1973). As a filmmaker Debord successfully dealt with alienation in film. -

Guy Debord and the Situationist International: Texts and Documents, Edited by Tom Mcdonough G D S I

G D S I OCTOBER BOOKS Rosalind E. Krauss, Annette Michelson, Yve-Alain Bois, Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, Hal Foster, Denis Hollier, and Mignon Nixon, editors Broodthaers, edited by Benjamin H. D. Buchloh AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism, edited by Douglas Crimp Aberrations, by Jurgis Baltrusˇaitis Against Architecture: The Writings of Georges Bataille, by Denis Hollier Painting as Model, by Yve-Alain Bois The Destruction of Tilted Arc: Documents, edited by Clara Weyergraf-Serra and Martha Buskirk The Woman in Question, edited by Parveen Adams and Elizabeth Cowie Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century, by Jonathan Crary The Subjectivity Effect in Western Literary Tradition: Essays toward the Release of Shakespeare’s Will, by Joel Fineman Looking Awry: An Introduction to Jacques Lacan through Popular Culture, by Slavoj Zˇizˇek Cinema, Censorship, and the State: The Writings of Nagisa Oshima, by Nagisa Oshima The Optical Unconscious, by Rosalind E. Krauss Gesture and Speech, by André Leroi-Gourhan Compulsive Beauty, by Hal Foster Continuous Project Altered Daily: The Writings of Robert Morris, by Robert Morris Read My Desire: Lacan against the Historicists, by Joan Copjec Fast Cars, Clean Bodies: Decolonization and the Reordering of French Culture, by Kristin Ross Kant after Duchamp, by Thierry de Duve The Duchamp Effect, edited by Martha Buskirk and Mignon Nixon The Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century, by Hal Foster October: The Second Decade, 1986–1996, edited by Rosalind Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois, Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, Hal Foster, Denis Hollier, and Silvia Kolbowski Infinite Regress: Marcel Duchamp 1910–1941, by David Joselit Caravaggio’s Secrets, by Leo Bersani and Ulysse Dutoit Scenes in a Library: Reading the Photograph in the Book, 1843–1875, by Carol Armstrong Neo-Avantgarde and Culture Industry: Essays on European and American Art from 1955 to 1975, by Benjamin H. -

The Genealogy of Dislocated Memory: Yugoslav Cinema After the Break

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses April 2014 The Genealogy of Dislocated Memory: Yugoslav Cinema after the Break Dijana Jelaca University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Jelaca, Dijana, "The Genealogy of Dislocated Memory: Yugoslav Cinema after the Break" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 10. https://doi.org/10.7275/vztj-0y40 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/10 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE GENEALOGY OF DISLOCATED MEMORY: YUGOSLAV CINEMA AFTER THE BREAK A Dissertation Presented by DIJANA JELACA Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2014 Department of Communication © Copyright by Dijana Jelaca 2014 All Rights Reserved THE GENEALOGY OF DISLOCATED MEMORY: YUGOSLAV CINEMA AFTER THE BREAK A Dissertation Presented by DIJANA JELACA Approved as to style and content by: _______________________________________ Leda Cooks, Chair _______________________________________ Anne Ciecko, Member _______________________________________ Lisa Henderson, Member _______________________________________ James Hicks, Member ____________________________________ Erica Scharrer, Department Head Department of Communication TO LOST CHILDHOODS, ACROSS BORDERS, AND TO MY FAMILY, ACROSS OCEANS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation is about a part of the world that I call “home” even though that place no longer physically exists. I belong to that “lost generation” of youth whose childhoods ended abruptly when Yugoslavia went up in flames. -

'To Realise the Ideal': Miscellaneous Remarks on Godard's Conceptual Processes Apropos of Sauve Qui Peut (La Vie)

‘To Realise the Ideal’: Miscellaneous Remarks on Godard’s Conceptual Processes Apropos of Sauve qui peut (la vie) •Richard Morris Made in 1979, Jean-Luc Godard’s Sauve qui peut photocopied images of the film’s three principal (la vie) occupies a uniquely pivotal position in the actors, Jacques Dutronc, Isabelle Huppert and director’s career, representing as it does the Miou-miou (replaced in the completed film by closing, culminatory opus of one decade and the Natalie Baye). These images rise up through the inaugural work of another. It is not, however, my machine as the paper feeds through it whilst the intention to address the specified film in a direct print head moves back and forth typing the way. I shall instead be talking around it, so to film’s title over the images. Meanwhile, Godard speak, with a view to exploring something of comments offscreen upon these two axes of how Godard actually conceives his works. It is my movement: one vertical, one horizontal, and on hope that in adopting this approach my the order of precedence between words and observations may acquire some more general images. He goes on to talk about the three relevance to Godard’s work throughout the characters whom he relates to differing abstract 1980s and beyond. vectors of movement, a theme I shall return to In embarking upon his first mainstream presently. There is little of any narrative feature since Tout va bien (1972) Godard found significance in this video-scenario beyond talk of himself faced with the problem of how to a desire to leave the big city, a desire originating incorporate something of the technical and with Denise (Miou-miou) who acts on it and conceptual flexibility and freedom which he had aspired to by Jacques (Dutronc) who lags attained as the co-director with Anne-Marie behind.1 Miéville of Sonimage, a kind of private audio- Beyond this, Godard muses on a variety of visual research institute for the production of subjects relating to the production of the film – innovative film, video and TV. -

New Histories of Hollywood Roundtable Moderated by Luci Marzola

Chris Cagle, Emily Carman, Mark Garrett Cooper, Kate Fortmueller, Eric Hoyt, Denise McKenna, Ross Melnick, Shelley Stamp New Histories of Hollywood Roundtable Moderated by Luci Marzola As part of this issue on “The System Beyond the Studios,” I sought not only to give scholars an opportunity to publish work that looks at specific cases reassessing the history of Hollywood, but I also wanted to look more broadly at the state of the field of American film history. As such, I assembled a roundtable of scholars who have been studying Hollywood through myriad lenses for most of their careers. I wanted to know, from their perspective, what were the current and future threads to be taken up in the study of this central topic in cinema and media studies. The roundtable discussion focuses on innovative methods, sources, and approaches that give us new insights into the study of Hollywood. Chris Cagle, Emily Carman, Mark Garrett Cooper, Kate Fortmueller, Eric Hoyt, Denise McKenna, Ross Melnick, and Shelley Stamp all participated while I moderated the conversation. It was conducted via email and Google docs in the fall of 2017. Each participant began by writing a brief response to a broad question on one topic – research, methodology, pedagogy, or the meaning of ‘Hollywood.’ These responses were then culled together and given follow up questions which were all placed in a Google drive folder. Over the course of two months, the participants added responses, provocations, and questions on each of the threads, while I added follow up questions to guide the discussion. When seen as a whole, this roundtable creates a snapshot of where the field of Hollywood history is at this moment. -

Israël Veut Un « Changement Complet » De La Politique Menée Par L'olp

LeMonde Job: WMQ0208--0001-0 WAS LMQ0208-1 Op.: XX Rev.: 01-08-97 T.: 11:23 S.: 111,06-Cmp.:01,11, Base : LMQPAG 27Fap:99 No:0328 Lcp: 196 CMYK CINQUANTE-TROISIÈME ANNÉE – No 16333 – 7,50 F SAMEDI 2 AOÛT 1997 FONDATEUR : HUBERT BEUVE-MÉRY – DIRECTEUR : JEAN-MARIE COLOMBANI Les athlètes Israël veut un « changement complet » à Athènes de la politique menée par l’OLP Rigor Mortis a Brigitte Aubert Participation record Benyamin Nétanyahou exige de Yasser Arafat qu’il éradique le terrorisme a aux championnats ISRAÉLIENS et responsables de Jérusalem. Les premiers accusent Le premier ministre a mis Yasser maine. « On ne peut faire avancer du monde l’Autorité palestinienne se sont l’OLP de ne pas en faire assez dans Arafat en demeure d’éradiquer le le processus diplomatique alors que renvoyés, jeudi 31 juillet, la res- la lutte contre le terrorisme ; les terrorisme et a juré qu’il n’y aurait l’Autorité palestinienne ne prend une nouvelle inédite ponsabilité de l’attentat qui, la seconds affirment que la politique pas de reprise des conversations pas les mesures minimales qu’elle qui s’ouvrent samedi veille, a fait quinze morts et plus du gouvernement de Benyamin israélo-palestiniennes tant qu’Is- s’est engagée à prendre contre les de cent cinquante blessés sur un Nétanyahou favorise la montée raël ne jugerait pas l’action de foyers du terrorisme », a dit M. Né- dames a des marchés les plus populaires de des extrémistes palestiniens. l’OLP satisfaisante dans ce do- tanyahou. « Il faut un changement du noir La pollution peut complet de politique de la part des Palestiniens, une campagne vigou- perturber les épreuves reuse, systématique et immédiate pour éliminer le terrorisme », a-t-il Les Dames a lancé, jeudi soir, à la télévision. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind.