The Letterists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond the Black Box: the Lettrist Cinema of Disjunction

Beyond the Black Box: The Lettrist Cinema of Disjunction ANDREW V. UROSKIE I was not, in my youth, particularly affected by cine - ma’s “Europeans” . perhaps because I, early on, developed an aversion to Surrealism—finding it an altogether inadequate (highly symbolic) envision - ment of dreaming. What did rivet my attention (and must be particularly distinguished) was Jean- Isidore Isou’s Treatise : as a creative polemic it has no peer in the history of cinema. —Stan Brakhage 1 As Caroline Jones has demonstrated, midcentury aesthetics was dominated by a rhetoric of isolated and purified opticality. 2 But another aesthetics, one dramatically opposed to it, was in motion at the time. Operating at a subterranean level, it began, as early as 1951, to articulate a vision of intermedia assemblage. Rather than cohering into the synaesthetic unity of the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk , works in this vein sought to juxtapose multiple registers of sensory experience—the spatial and the temporal, the textual and the imagistic—into pieces that were intentionally disjunc - tive and lacking in unity. Within them, we can already observe questions that would come to haunt the topos of avant-garde film and performance in the coming decades: questions regarding the nature and specificity of cinema, its place within artistic modernism and mass culture, the institutions through which it is presented, and the possible modes of its spectatorial engagement. Crucially associated with 1. “Inspirations,” in The Essential Brakhage , ed. Bruce McPherson (New York: McPherson & Co., 2001), pp. 208 –9. Mentioned briefly across his various writings, Isou’s Treatise was the subject of a 1993 letter from Brakhage to Frédérique Devaux on the occasion of her research for Traité de bave et d’eternite de Isidore Isou (Paris: Editions Yellow Now, 1994). -

Letterism 1947-2014 Vol. 1

The Future is Unwritten: Letterism 1947-2014 Vol. 1 Catalog 17 Division Leap 6635 N. Baltimore Ave. Ste. 111 Portland, OR 97203 www.divisionleap.com [email protected] 503 206 7291 “Radically anticipating Herbert Marcuse, Paul Goodman, and their Letterism is a movement whose influence is as widespread as it is unacknowledged. From punk to concrete poetry to experimental film, from the development of youth culture to the student uprisings of 1968 and epigones in the 1960s new left, Isou the formation of the Situationist International, most postwar avant-garde movements owe a debt to it’s rev- produced an analysis of youth as olutionary theories, yet it remains largely overlooked in studies of the period (some notable exceptions are listed in the bibliography that follows the text). an inevitably revolutionary social sector - revolutionary on its own This catalog contains over one hundred items devoted to Letterism and Inismo. To the best of our knowl- edge it is the first devoted to either of these movements in the US. It contains a number of publications terms, which meant that the terms which have little or no institutional representation on these shores, and represents a valuable opportunity for of revolution had to be seen in a future research. new way.” A number of the items in this catalog were collected by the anarchist scholar Pietro Ferrua, who was closely associated with members of both Letterism and Inismo and who has written a great deal about both move- ments. Ferrua organized the first international conference on Letterism here in Portland in 1979 [see #62]. -

Guy Debord and the Situationist International: Texts and Documents, Edited by Tom Mcdonough G D S I

G D S I OCTOBER BOOKS Rosalind E. Krauss, Annette Michelson, Yve-Alain Bois, Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, Hal Foster, Denis Hollier, and Mignon Nixon, editors Broodthaers, edited by Benjamin H. D. Buchloh AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism, edited by Douglas Crimp Aberrations, by Jurgis Baltrusˇaitis Against Architecture: The Writings of Georges Bataille, by Denis Hollier Painting as Model, by Yve-Alain Bois The Destruction of Tilted Arc: Documents, edited by Clara Weyergraf-Serra and Martha Buskirk The Woman in Question, edited by Parveen Adams and Elizabeth Cowie Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century, by Jonathan Crary The Subjectivity Effect in Western Literary Tradition: Essays toward the Release of Shakespeare’s Will, by Joel Fineman Looking Awry: An Introduction to Jacques Lacan through Popular Culture, by Slavoj Zˇizˇek Cinema, Censorship, and the State: The Writings of Nagisa Oshima, by Nagisa Oshima The Optical Unconscious, by Rosalind E. Krauss Gesture and Speech, by André Leroi-Gourhan Compulsive Beauty, by Hal Foster Continuous Project Altered Daily: The Writings of Robert Morris, by Robert Morris Read My Desire: Lacan against the Historicists, by Joan Copjec Fast Cars, Clean Bodies: Decolonization and the Reordering of French Culture, by Kristin Ross Kant after Duchamp, by Thierry de Duve The Duchamp Effect, edited by Martha Buskirk and Mignon Nixon The Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century, by Hal Foster October: The Second Decade, 1986–1996, edited by Rosalind Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois, Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, Hal Foster, Denis Hollier, and Silvia Kolbowski Infinite Regress: Marcel Duchamp 1910–1941, by David Joselit Caravaggio’s Secrets, by Leo Bersani and Ulysse Dutoit Scenes in a Library: Reading the Photograph in the Book, 1843–1875, by Carol Armstrong Neo-Avantgarde and Culture Industry: Essays on European and American Art from 1955 to 1975, by Benjamin H. -

Jean-Michel-Mension-Tribe-Translated-Donald-Nicholson-Smith-1.Pdf

JEAN-MICHEL MENSION CONVERSATIONS WITH GERARD BERREB Y AND FRANCESCO MILO TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH BY DONALD NICHOLSON-SMITH Contributions to the History of the Situationist International and Its Time, Vol. I CITY LIGHTS BOOKS SAN FRANCISCO © 2001 by Donald Nicholson-Smith for this translation © 1998 by Editions Allia, Paris, for La Tribu by Jean-Michel Mension © by Ed van der Elsken{fhe Netherlands Photo Archives for his photographs All rights reserved 10 98 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Cover & book design: Stefan Gutermuth/doubleu-gee Editor: James Brook This work, published as part of the program of aid for publication, received support from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Cultural Service of the French Embassy in the United States. Cet ouvrage publie dans Ie cadre du programme d'aide a la publication beneficie du soutien du Ministere des Affaires Etrangeres et du Service Culture I de l'Ambassade de France represente aux Etats-Unis. Mension, Jean-Michel. [Tribu. English] The tribe / by Jean-Michel Mension ; translated from the French by Donald Nicholson-Smith. p. cm. Interviews with Gerard Berreby and Francesco Milo. ISBN 0-87286-392-1 1. Mension, Jean-Michel-Friends and associates-Interviews. 2. Paris (France)-intellectual life-20th century-Interviews. 3. Radicalism-France-Paris. l. Berreby, Gerard. II. Milo, Francesco. III. Title. DC715 .M39413 2001 944'.36083'092-dc21 2001042129 CITY LIGHTS BOOKS are edited by Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Nancy J. Peters and published at the City Lights Bookstore, 261 Columbus Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94133. Visit us on the Web at www.citylights.com. -

Hartnett Dissertation

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Recorded Objects: Time-Based Technologically Reproducible Art, 1954-1964 A Dissertation Presented by Gerald Hartnett to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History and Criticism Stony Brook University August 2017 Stony Brook University 2017 Copyright by Gerald Hartnett 2017 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Gerald Hartnett We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Andrew V. Uroskie – Dissertation Advisor Associate Professor, Department of Art Jacob Gaboury – Chairperson of Defense Assistant Professor, Department of Art Brooke Belisle – Third Reader Assistant Professor, Department of Art Noam M. Elcott, Outside Reader Associate Professor, Department of Art History, Columbia University This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School Charles Taber Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation Recorded Objects: Time-Based, Technologically Reproducible Art, 1954-1964 by Gerald Hartnett Doctor of Philosophy in Art History and Criticism Stony Brook University 2017 Illuminating experimental, time-based, and technologically reproducible art objects produced between 1954 and 1964 to represent “the real,” this dissertation considers theories of mediation, ascertains vectors of influence between art and the cybernetic and computational sciences, and argues that the key practitioners responded to technological reproducibility in three ways. First of all, writers Guy Debord and William Burroughs reinvented appropriation art practice as a means of critiquing retrograde mass media entertainments and reportage. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. I am using the terms ‘space’ and ‘place’ in Michel de Certeau’s sense, in that ‘space is a practiced place’ (Certeau 1988: 117), and where, as Lefebvre puts it, ‘(Social) space is a (social) product’ (Lefebvre 1991: 26). Evelyn O’Malley has drawn my attention to the anthropocentric dangers of this theorisation, a problematic that I have not been able to deal with fully in this volume, although in Chapters 4 and 6 I begin to suggest a collaboration between human and non- human in the making of space. 2. I am extending the use of the term ‘ extra- daily’, which is more commonly associated with its use by theatre director Eugenio Barba to describe the per- former’s bodily behaviours, which are moved ‘away from daily techniques, creating a tension, a difference in potential, through which energy passes’ and ‘which appear to be based on the reality with which everyone is familiar, but which follow a logic which is not immediately recognisable’ (Barba and Savarese 1991: 18). 3. Architectural theorist Kenneth Frampton distinguishes between the ‘sceno- graphic’, which he considers ‘essentially representational’, and the ‘architec- tonic’ as the interpretation of the constructed form, in its relationship to place, referring ‘not only to the technical means of supporting the building, but also to the mythic reality of this structural achievement’ (Frampton 2007 [1987]: 375). He argues that postmodern architecture emphasises the scenographic over the architectonic and calls for new attention to the latter. However, in contemporary theatre production, this distinction does not always reflect the work of scenographers, so might prove reductive in this context. -

Jean-Jacques Thomas Romance Languages and Literatures University at Buffalo

Jean-Jacques Thomas Romance Languages and Literatures University at Buffalo Isidore Isou’s spirited letters It is paradoxical to consider that today Isidore Isou, probably one of the least known Romanian-born French writers and philosophers could be the most famous and the best considered Romanian intellectual of the twentieth century. It is probably his insatiable desire for public fame and recognition that prevented him from achieving such a possible destiny at least at par with Tristan Tzara or Eugène Ionesco. An extremely well-read intellectual, an indefatigable writer and thinker, there are very few aspects of human knowledge, be they letters, arts or sciences that, at one point or another in his life, did not attract his intellectual attention and his knowledgeable study. Totally convinced of his own worth and of his own exceptional nature, in several essays he compares his nature and intellectual status to that of Leonardo da Vinci, estimating even that his own capacity to construct a unified system of organization of human knowledge placed him above da Vinci who could only systematize and understand fragmentary aspects of human knowledge.1 For many of his contemporaries, it is this hubris (megalomania) coupled with a sharp and relentless criticism of the mediocrity of the other intellectuals, writers and thinkers of the immediate post WWII period in France that explains Isou’s paradoxical status as a marginal intellectual generally at odds with different intellectual and literary movements that span the 1945-1970 period in France. Two terms are directly related to his early literary accomplishments and innovations: Letterism [lettrisme] and metagraphy [métagraphie]. -

A Study of the Work of Roland Barthes, Isidore Isou, François Dufrêne and Daniel Buren Jennifer Farrell

The Effacement of Myth: A Study of the Work of Roland Barthes, Isidore Isou, François Dufrêne and Daniel Buren Jennifer Farrell In 1953, Roland Barthes published his celebrated text Writing Dufrêne originally became interested in lettrisme through Degree Zero in which he described the crisis facing contem- the writings of Isidore Isou, a poet, critic, and philosopher of porary literature.1 Barthes’s basic premise was that literature language and art who claimed credit for the invention and had moved from the Classical to the modern or bourgeois form. development of lettrisme. Also known as hypergraphie, and As a result, language had ceased to function as a transparent super-écriture, lettrisme was a movement based on the plastic means of communication, becoming instead an object, and in use of the letter or sign which was not to signify anything this capacity, was something the modern writer was forced to other than itself, thus transcending traditional conventions of confront. It was this confrontation that structured modern meaning by emphasizing the figure or form of the sign of the writing. The work of the décollage artist and lettriste poet letter over representation. François Dufrêne reflected a similar conception of language In addition to revising language, Isou proposed a radi- as object in his search for a neutral or “colorless” form of cally revised history of modernism that was to be almost ex- language. Dufrêne, however, did not approach his investiga- clusively French, beginning with Impressionism and culmi- tion solely as a theoretician, but rather as an artist and a poet nating in lettrisme. -

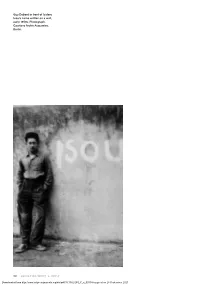

22 Doi:10.1162/GREY a 00114 Guy Debord in Front of Isidore Isou's Name Written on a Wall, Early 1950S. Photograph. Courtesy Ar

Guy Debord in front of Isidore Isou’s name written on a wall, early 1950s. Photograph. Courtesy Archiv Acquaviva, Berlin. 22 doi:10.1162/GREY_a_ 00114 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/GREY_a_00114 by guest on 28 September 2021 Hurlements en faveur de vous KAIRA M. CABAÑAS I loVe the cinema When it is insolent and does What it is not sUpposed to do. —Daniel in Isidore IsoU, Traité de baVe et d’éternité , 1951 GUY Debord’s first pUblic appearance in print occUrred in the pages of Ion , a single-issUe magaZine dedicated eXclUsiVelY to Lettrist Work in cinema and pUblished Under the direction of Marc-Gilbert GUillaUmin (other - Wise knoWn as Marc’O) in April 1952. Ion inclUded Isidore IsoU’s lengthY treatise “ EsthétiqUe dU cinéma ” and Marc’O’s “ Première manifestation d’Un cinéma nUcléaire ,” as Well as the scripts for Gil J Wolman’s L’anticoncept , François DUfrêne’s TamboUrs dU jUgement premier , and Gabriel Pomerand’s La légende crUelle . Yet What is often forgotten is that the issUe also inclUded Debord’s “ Prolégomènes à toUt cinéma fUtUr ” as a preface to the original script for his film HUrlements en faVeUr de Sade (HoWls for Sade, 1952), Which at this point also inclUded an image track. The half-page “ Prolégomènes ” sitUates HUrlements Within the Lettrist aesthetic in cinema as elaborated primarilY bY IsoU. Debord Writes, “MY film Will remain among the most important in the historY of the redUc - tiVe hYpostasis of cinema throUgh a terrorist disorganiZation of the dis - crepant.” 1 With the inVocation of discrepant Debord confesses his film’s recoUrse to montage discrépant (discrepant editing), or What IsoU first theoriZed in the pages of “ EsthétiqUe dU cinéma ” as the pUrposefUl non - sYnchroniZation of soUnd and image in film. -

Music, Lettrism, Avant-Gardes

H-Announce Invisible Republic: Music, Lettrism, Avant-Gardes Announcement published by Anabela Duarte on Monday, March 13, 2017 Type: Call for Papers Date: March 8, 2017 to April 28, 2017 Location: Portugal Subject Fields: American History / Studies, Cultural History / Studies, Music and Music History, Popular Culture Studies, Humanities PRESENTATION In Invisible Republic: Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes (1997), Greil Marcus charts a countercultural sound map, a kind of laboratory where a new language is being forged. This is where, Marcus argues, we can locate the true voice of the century, a new consciousness, the alchemy of an undiscovered country. From this starting-point, we propose a journey into the tangled relationship between music, the avant-gardes and counterculture. In 1942, Isidore Isou, a Jew from Romania, created in Bucharest an artistic and cultural trend that claimed for a “new republic” of letters. He brought it to Paris in 1945, and this became “Lettrism”, one of the most inventive but also one of the most unknown movements of the post-war avant-gardes. In 1947, he published a manifesto, an introduction to a new poetry and a new music that set forth Lettrism as a general movement of creation, a poetry liberated from words and syntax, and a number of propositions that constitute a fundamental historical link between the modern and the contemporary. Lettrism, it has been argued, was the progenitor of future upheavals and revolts, such as May ‘68, Punk, Situationism, Fluxus, among others. Music and sound, in this context, are powerful instruments of destruction and/or reconfiguration of language and the Arts. -

The End of the Age of Divinity � (On the Death of Isou)

The End of the Age of Divinity (On the Death of Isou) Introduction: Union and Multitude of the Proletariat. I The Talmud in Tractate Kesubos (p. 111a), teaches that Jews shall not use human force to bring about the establishment of a Jewish state before the coming of the universally accepted Moshiach (Messiah from the House of David). We hold that Isidore Isou, who published the Lettrist Manifesto in 1946 predating the inception of Israel in 1948, was in fact the Moshiach and that his death in 2007 marks the end of the Age of Divinity. II It was the Islamic Ḥur ūfiyyah (Lettrist) Fa Ŝlu l-Lāh Astar-Ābādī (Naimi), the Seal of the Saints whose death in 1395 opened the Age of Divinity ( Uluhiyyat ). It is closed by Isidre Isou, who we proclaim as the Seal of Divinity. We hereby declare the Age of the Proletariat. III Observed from close up, ie from a worker who is involved more directly in the process/time/space of the event, this may appear as a ‘singularity’ in so-called ‘space-time’. However from a wider perspective – a distant worker of group of workers, this and these event/s are vertices in temporal space and mark the progression from 0 and 1 dimensional 1 time to the revealing of the 2 nd and 3 rd dimensions (the Trimension 2) of time. IV While the religious problem in Isou’s Lettrism was answered by ‘the movement’ with a rejection of the proletariat and with the worship of the innovator – the creator, this sell out, this mystification, this mythologisation, this anti-materialist basis and orientation, was in fact also evident in the work of Isou’s best critic and the developer of the Lettrist metagraphy and hypergraphy into situgraphy, Asger Jorn. -

One Plus One Pr Oct 26

Mihai Nicodim Gallery „ONE PLUS ONE EQUALS ONE” Marcel Iancu, Isidore Isou, Gherasim Luca, Ana Lupas and Teodor Graur Opening Reception: Friday, October 26, 2012, 6 - 9 pm Exhibition Dates: October 26 – December 8, 2012 Mihai Nicodim Gallery is pleased to present “One Plus One Equals One” an exhibition that brings together three artists belonging to the Romanian-Jewish avant-garde of the 1920s and 40s - Marcel Iancu, Isidore Isou and Gherasim Luca, and two other artists, Ana Lupas - belonging to the generation of the 60s, and Teodor Graur – the 90s. The exhibition contains a series of documentary works, avant-garde journals, some of them exhibited for the first time, manuscripts and experimental etchings. The Romanian-Jewish avant-garde from the early decades of the 20th century took by storm the art-world through their fearless experimentation and proposed a radically revolutionary method that pushed beyond the limit the changes engendered by the aesthetic attitude introduced by modernism. Marcel Iancu (1895 - 1984) was a Romanian-Israeli artist and art theorist, who, alongside his poet friend Tristan Tzara co-founded and played a crucial role in the development of DADA. He was also a leading exponent of Constructivism in Eastern Europe. Along with Tristan Tzara he co-founded the anti-establishment Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich. The first-ever Dada event took place in Cabaret Voltaire, Zurich, on Feb 1916. Isidore Isou (January 31, 1925 – July 28, 2007) was a Romanian-born French poet, film critic and visual artist. He was the founder of Lettrism, an art and literary movement, which owed inspiration to Dada and Surrealism.