The Space Between: How We Understood, Valued, and Governed the Ocean Through the Process of Marine Science and Emerging Technologies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life Cycle and Early Development of the Thecosomatous Pteropod Limacina Retroversa in the Gulf of Maine, Including the Effect of Elevated CO2 Levels

Life cycle and early development of the thecosomatous pteropod Limacina retroversa in the Gulf of Maine, including the effect of elevated CO2 levels Ali A. Thabetab, Amy E. Maasac*, Gareth L. Lawsona and Ann M. Tarranta a. Biology Department, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA 02543 b. Zoology Dept., Faculty of Science, Al-Azhar University in Assiut, Assiut, Egypt. c. Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences, St. George’s GE01, Bermuda *Corresponding Author, equal contribution with lead author Email: [email protected] Phone: 441-297-1880 x131 Keywords: mollusc, ocean acidification, calcification, mortality, developmental delay Abstract Thecosome pteropods are pelagic molluscs with aragonitic shells. They are considered to be especially vulnerable among plankton to ocean acidification (OA), but to recognize changes due to anthropogenic forcing a baseline understanding of their life history is needed. In the present study, adult Limacina retroversa were collected on five cruises from multiple sites in the Gulf of Maine (between 42° 22.1’–42° 0.0’ N and 69° 42.6’–70° 15.4’ W; water depths of ca. 45–260 m) from October 2013−November 2014. They were maintained in the laboratory under continuous light at 8° C. There was evidence of year-round reproduction and an individual life span in the laboratory of 6 months. Eggs laid in captivity were observed throughout development. Hatching occurred after 3 days, the veliger stage was reached after 6−7 days, and metamorphosis to the juvenile stage was after ~ 1 month. Reproductive individuals were first observed after 3 months. Calcein staining of embryos revealed calcium storage beginning in the late gastrula stage. -

Fly High Dive Deep

FLY HIGH DIVE DEEP COMMERCIAL DIVING REMOTE OPERATED VEHICLES SPACE EXPLORATION HUMAN LIFE SCIENCE WWW.BLUEABYSS.UK THE PROMISE Blue Abyss is among the most ground-breaking projects of its time. Designed to support the commercial diving, remote operated vehicle, human spaceflight and human life science sectors, Blue Abyss promises to be Europe’s premier extreme environment research, development and training facility. This unique aquatic centre will house the world’s largest and deepest indoor pool, alongside: hyper and hypobaric chambers; the Kuehnegger Human Performance Centre; a micro-gravity simulation suspension suite for replicating the effects of weightlessness and hypo-gravity; amphitheatre and classrooms; cafeteria and 120-bed hotel. ASTRONAUTS AND “OTHER SPACE PROFESSIONALS WILL WANT TO COME FROM AROUND THE WORLD TO USE THE MASSIVE, YET CONTROLLED, ENVIRONMENT TO REDUCE RISK IN SPACE. I CAN SEE PLENTY OF INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIONS AND BUSINESS VENTURES STARTING LIFE WITHIN BLUE ABYSS. DR HELEN SHARMAN” FIRST BRITISH CITIZEN IN SPACE 1 Full onsite mission control, hypo and hyperbaric chambers Crane and lifting platform (30 tonnes) Training/experience mock-ups Pool 50m x 40m on surface Multi-level functionality including ‘Astrolab’ at 12m 50m at deepest point / THE MULTI-LEVEL POOL WILL CONTAIN 38,000M3 OF WATER, EXCEEDING ALL OTHER FACILITIES IN EXISTENCE BOTH IN TERMS OF VOLUME AND DEPTH. Image courtesy of Cityscape Digital 2 3 THE POSSIBILITIES Blue Abyss is a truly pioneering project that will extend the Blue Abyss is designed to cater for Space environment simulation possibilities for education, commercial and scientific research, on one hand, and freediving on the other, with a huge variety of development and training beyond anything that exists today. -

An Overview of the Fossil Record of Pteropoda (Mollusca, Gastropoda, Heterobranchia)

Cainozoic Research, 17(1), pp. 3-10 June 2017 3 An overview of the fossil record of Pteropoda (Mollusca, Gastropoda, Heterobranchia) Arie W. Janssen1 & Katja T.C.A. Peijnenburg2, 3 1 Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Marine Biodiversity, Fossil Mollusca, P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The Nether lands; [email protected] 2 Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Marine Biodiversity, P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands; Katja.Peijnen [email protected] 3 Institute for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Dynamics (IBED), University of Amsterdam, P.O. Box 94248, 1090 GE Am sterdam, The Netherlands. Manuscript received 23 January 2017, revised version accepted 14 March 2017 Based on the literature and on a massive collection of material, the fossil record of the Pteropoda, an important group of heterobranch marine, holoplanktic gastropods occurring from the late Cretaceous onwards, is broadly outlined. The vertical distribution of genera is illustrated in a range chart. KEY WORDS: Pteropoda, Euthecosomata, Pseudothecosomata, Gymnosomata, fossil record Introduction Thecosomata Mesozoic Much current research focusses on holoplanktic gastro- pods, in particular on the shelled pteropods since they The sister group of pteropods is now considered to belong are proposed as potential bioindicators of the effects of to Anaspidea, a group of heterobranch gastropods, based ocean acidification e.g.( Bednaršek et al., 2016). This on molecular evidence (Klussmann-Kolb & Dinapoli, has also led to increased interest in delimiting spe- 2006; Zapata et al., 2014). The first known species of cies boundaries and distribution patterns of pteropods pteropods in the fossil record belong to the Limacinidae, (e.g. Maas et al., 2013; Burridge et al., 2015; 2016a) and are characterised by sinistrally coiled, aragonitic and resolving their evolutionary history using molecu- shells. -

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS of the 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project March 2018 DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project Citation: Aguilar, R., García, S., Perry, A.L., Alvarez, H., Blanco, J., Bitar, G. 2018. 2016 Deep-sea Lebanon Expedition: Exploring Submarine Canyons. Oceana, Madrid. 94 p. DOI: 10.31230/osf.io/34cb9 Based on an official request from Lebanon’s Ministry of Environment back in 2013, Oceana has planned and carried out an expedition to survey Lebanese deep-sea canyons and escarpments. Cover: Cerianthus membranaceus © OCEANA All photos are © OCEANA Index 06 Introduction 11 Methods 16 Results 44 Areas 12 Rov surveys 16 Habitat types 44 Tarablus/Batroun 14 Infaunal surveys 16 Coralligenous habitat 44 Jounieh 14 Oceanographic and rhodolith/maërl 45 St. George beds measurements 46 Beirut 19 Sandy bottoms 15 Data analyses 46 Sayniq 15 Collaborations 20 Sandy-muddy bottoms 20 Rocky bottoms 22 Canyon heads 22 Bathyal muds 24 Species 27 Fishes 29 Crustaceans 30 Echinoderms 31 Cnidarians 36 Sponges 38 Molluscs 40 Bryozoans 40 Brachiopods 42 Tunicates 42 Annelids 42 Foraminifera 42 Algae | Deep sea Lebanon OCEANA 47 Human 50 Discussion and 68 Annex 1 85 Annex 2 impacts conclusions 68 Table A1. List of 85 Methodology for 47 Marine litter 51 Main expedition species identified assesing relative 49 Fisheries findings 84 Table A2. List conservation interest of 49 Other observations 52 Key community of threatened types and their species identified survey areas ecological importanc 84 Figure A1. -

Xoimi AMERICAN COXCIIOLOGY

S31ITnS0NIAN MISCEllANEOUS COLLECTIOXS. BIBLIOGIIAPHY XOimi AMERICAN COXCIIOLOGY TREVIOUS TO THE YEAR 18G0. PREPARED FOR THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION BY . W. G. BINNEY. PART II. FOKEIGN AUTHORS. WASHINGTON: SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION. JUNE, 1864. : ADYERTISEMENT, The first part of the Bibliography of American Conchology, prepared for the Smithsonian Institution by Mr. Binuey, was published in March, 1863, and embraced the references to de- scriptions of shells by American authors. The second part of the same work is herewith presented to the public, and relates to species of North American shells referred to by European authors. In foreign works binomial authors alone have been quoted, and no species mentioned which is not referred to North America or some specified locality of it. The third part (in an advanced stage of preparation) will in- clude the General Index of Authors, the Index of Generic and Specific names, and a History of American Conchology, together with any additional references belonging to Part I and II, that may be met with. JOSEPH HENRY, Secretary S. I. Washington, June, 1864. (" ) PHILADELPHIA COLLINS, PRINTER. CO]^TENTS. Advertisement ii 4 PART II.—FOREIGN AUTHORS. Titles of Works and Articles published by Foreign Authors . 1 Appendix II to Part I, Section A 271 Appendix III to Part I, Section C 281 287 Appendix IV .......... • Index of Authors in Part II 295 Errata ' 306 (iii ) PART II. FOEEIGN AUTHORS. ( V ) BIBLIOGRxVPHY NOETH AMERICAN CONCHOLOGY. PART II. Pllipps.—A Voyage towards the North Pole, &c. : by CON- STANTiNE John Phipps. Loudou, ITTJc. Pa. BIBLIOGRAPHY OF [part II. FaliricillS.—Fauna Grcenlandica—systematice sistens ani- malia GrcEulandite occidentalis liactenus iudagata, &c., secun dum proprias observatioues Othonis Fabricii. -

Distribution Patterns of Pelagic Gastropods at the Cape Verde Islands Holger Ossenbrügger

Distribution patterns of pelagic gastropods at the Cape Verde Islands Holger Ossenbrügger* Semester thesis 2010 *GEOMAR | Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel Marine Ecology | Evolutionary Ecology of Marine Fishes Düsternbrooker Weg 20 | 24105 Kiel | Germany Contact: [email protected] Contents 1. Introduction . .2 1.1. Pteropods . 2 1.2. Heteropods . 3 1.3. Hydrography . 4 2. Material and Methods . 5 3. Results and Discussion . 7 3.1. Pteropods . 7 3.1.1. Species Composition . 7 3.1.2. Spatial Density Distribution near Senghor Seamount . .. 9 3.1.3. Diel Vertical Migration . 11 3.2. Heteropods . 17 3.2.1. Species Composition . .17 3.2.2. Spatial Density Distribution near Senghor Seamount . .17 3.2.3. Diel Vertical Migration . 18 4. Summary and directions for future research . 19 References . 20 Acknowledgements . 21 Attachment . .22 1. Introduction 1.1. Pteropods Pteropods belong to the phylum of the Mollusca. They are part of the class Gastropoda and located in the order Ophistobranchia. The pteropods are divided into the orders Thecosomata and Gymnosomata. They are small to medium sized animals, ranging from little more than 1mm for example in many members of the Genus Limacina to larger species such as Cymbulia peroni, which reaches a pseudoconch length of 65mm. The mostly shell bearing Thecosomata are known from about 74 recent species worldwide and are divided into five families. The Limacinidae are small gastropods with a sinistrally coiled shell; they can completely retract their body into the shell. Seven recent species of the genus Limacina are known. The Cavoliniidae is the largest of the thecosomate families with about 47 species with quite unusually formed shells. -

Safe Transportation Systems for Sustainable Commercial Human Spaceflight / Small Launchers: Concepts and Operations (Part II) (9-D6.2)

69th International Astronautical Congress 2018 Paper ID: 47238 IAF SPACE TRANSPORTATION SOLUTIONS AND INNOVATIONS SYMPOSIUM (D2) Safe Transportation Systems for Sustainable Commercial Human Spaceflight / Small Launchers: Concepts and Operations (Part II) (9-D6.2) Author: Mr. Charles Lauer Blue Abyss, United States, [email protected] Mr. Simon Evetts Blue Abyss, United Kingdom, [email protected] Mr. John Vickers Blue Abyss, United Kingdom, [email protected] A NEW COMMERCIAL SPACEFLIGHT TRAINING PROGRAM FOR SUBORBITAL AND ORBITAL SPACEFLIGHT Abstract After many years of engineering and development, suborbital and orbital commercial spaceflight vehi- cles are finally expected to enter service in the next year or two. Blue Origin is already flying FAA/AST licensed unmanned commercial suborbital research flights from their private spaceport in west Texas and expect to begin testing their New Shepard vehicle with onboard crews this year. Virgin Galactic should begin powered flight tests on the second SpaceShipTwo in 2018 with commercial suborbital tourism flights potentially beginning in 2019. For orbital commercial spaceflight, SpaceX and Boeing should both be- gin flight testing and enter initial commercial flight service to the ISS before the close of 2019. These suborbital and orbital vehicle programs now provide a solid business foundation for the development of dedicated commercial spaceflight training programs to enable safe and enjoyable spaceflight experiences for commercial customers. Blue Abyss Ltd. is developing a dedicated spaceflight training facility and associated training curricula in Central Bedfordshire about an hour north of central London. The facility will be located at the former RAF Henlow base as part of a regional development plan for the Oxford { Cambridge Technology Corridor. -

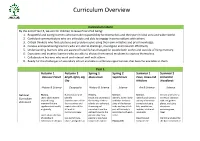

Curriculum Overview

Curriculum Overview Curriculum Intent By the end of Year 6, we aim for children to leave Priors Hall being: 1. Respectful and caring learners who can take responsibility for themselves and their part in local area and wider world. 2. Confident communicators who are articulate and able to engage in conversations with others. 3. Critical thinkers who find solutions and problem solve using their own initiative and prior knowledge. 4. Curious and questioning learners who are able to challenge, investigate and research effectively. 5. Understanding learners who are aware of how life has changed for people both within and outside of living memory. 6. Expressive and creative learners who are able to choose from varied mediums to express themselves. 7. Collaborative learners who work and interact well with others. 8. Ready for the challenges of secondary school and able to embrace opportunities that become available to them. Year 1 Autumn 1 Autumn 2 Spring 1 Spring 2 Summer 1 Summer 2 Dinosaur Planet Bright Lights, Big Moon Zoom Superheroes Paws, Claws and Enchanted City Whiskers Woodlands History & Science Geography History & Science Science Art & Science Science National History: Name, locate and History: Science: Science: Identify and name a Curriculum Learn about events identify Know and understand Identify, name, draw identify and name a variety of common beyond living characteristics of the the history of these and label the basic variety of common wild and garden statement memory that are four countries and islands as a coherent, parts of the human animals including plants, including significant nationally capital cities of the chronological body and say which fish, amphibians, deciduous or globally UK and its narrative, from the part of the body is reptiles, birds and and evergreen surrounding seas. -

Phylogenetic Analysis of Thecosomata Blainville, 1824

Phylogenetic Analysis of Thecosomata Blainville, 1824 (Holoplanktonic Opisthobranchia) Using Morphological and Molecular Data Emmanuel Corse, Jeannine Rampal, Corinne Cuoc, Nicolas Pech, Yvan Perez, André Gilles To cite this version: Emmanuel Corse, Jeannine Rampal, Corinne Cuoc, Nicolas Pech, Yvan Perez, et al.. Phylogenetic Analysis of Thecosomata Blainville, 1824 (Holoplanktonic Opisthobranchia) Using Morphological and Molecular Data. PLoS ONE, Public Library of Science, 2013, 8 (4), pp.59439 - 59439. 10.1371/jour- nal.pone.0059439. hal-01771570 HAL Id: hal-01771570 https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01771570 Submitted on 19 Apr 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License Phylogenetic Analysis of Thecosomata Blainville, 1824 (Holoplanktonic Opisthobranchia) Using Morphological and Molecular Data Emmanuel Corse*, Jeannine Rampal, Corinne Cuoc, Nicolas Pech, Yvan Perez., Andre´ Gilles. IMBE (UMR CNRS 7263, IRD 237) Evolution Ge´nome Environnement, Aix-Marseille Universite´, Marseille, France Abstract Thecosomata is a marine zooplankton group, which played an important role in the carbonate cycle in oceans due to their shell composition. So far, there is important discrepancy between the previous morphological-based taxonomies, and subsequently the evolutionary history of Thecosomata. -

Canada's Arctic Marine Atlas

CANADA’S ARCTIC MARINE ATLAS This Atlas is funded in part by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. I | Suggested Citation: Oceans North Conservation Society, World Wildlife Fund Canada, and Ducks Unlimited Canada. (2018). Canada’s Arctic Marine Atlas. Ottawa, Ontario: Oceans North Conservation Society. Cover image: Shaded Relief Map of Canada’s Arctic by Jeremy Davies Inside cover: Topographic relief of the Canadian Arctic This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0 or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. All photographs © by the photographers ISBN: 978-1-7752749-0-2 (print version) ISBN: 978-1-7752749-1-9 (digital version) Library and Archives Canada Printed in Canada, February 2018 100% Carbon Neutral Print by Hemlock Printers © 1986 Panda symbol WWF-World Wide Fund For Nature (also known as World Wildlife Fund). ® “WWF” is a WWF Registered Trademark. Background Image: Phytoplankton— The foundation of the oceanic food chain. (photo: NOAA MESA Project) BOTTOM OF THE FOOD WEB The diatom, Nitzschia frigida, is a common type of phytoplankton that lives in Arctic sea ice. PHYTOPLANKTON Natural history BOTTOM OF THE Introduction Cultural significance Marine phytoplankton are single-celled organisms that grow and develop in the upper water column of oceans and in polar FOOD WEB The species that make up the base of the marine food Seasonal blooms of phytoplankton serve to con- sea ice. Phytoplankton are responsible for primary productivity—using the energy of the sun and transforming it via pho- web and those that create important seafloor habitat centrate birds, fishes, and marine mammals in key areas, tosynthesis. -

Notes on the Systematics, Morphology and Biostratigraphy of Fossil Holoplanktonic Mollusca, 22 1

B76-Janssen-Grebnev:Basteria-2010 11/07/2012 19:23 Page 15 Notes on the systematics, morphology and biostratigraphy of fossil holoplanktonic Mollusca, 22 1. Further pelagic gastropods from Viti Levu, Fiji Archipelago Arie W. Janssen Netherlands Centre for Biodiversity Naturalis (Palaeontology Department), P.O. Box 9517, NL-2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands; currently: 12, Triq tal’Hamrija, Xewkija XWK 9033, Gozo, Malta; [email protected] Andrew Grebneff † Formerly : University of Otago, Geology Department, Dunedin, New Zealand himself during holiday trips in 1995 and 1996, also from Viti Two localities in the island of Viti Levu, Fiji Archipelago, Levu, the largest island in the Fiji archipelago. Following an yielded together 28 species of Heteropoda (3 species) and initial evaluation of this material it remained unstudied, 15 Pteropoda (25 species). Two samples from Tabataba, NW however, for a long time . A first inspection acknowledged Viti Levu, indicate an age of late Miocene to early Pliocene. Andrew’s impression that part of the samples was younger Two samples from Waila, SE Viti Levu, signify an age of than the earlier described material and therefore worth Pliocene (Piacenzian) and closely resemble coeval assem - publishing. blages described from Pangasinan, Philippines. After the untimely death of Andrew Grebneff in July 2010 (see the website of the University of Otago, New Key words: Gastropoda, Pterotracheoidea, Limacinoidea, Zealand (http://www.otago.ac.nz/geology/news/files/ Cavolinioidea, Clionoidea, late Miocene, Pliocene, biostratigraphy, andrew_ grebneff.html) it was decided to restart the study Fiji archipelago. of those samples and publish the results with Andrew’s name added as a valuable co-author, as he not only collected the specimens but also participated in discussions on their Introduction taxonomy and age. -

Euthecosomatous Pteropods (Mollusca) in the Gulf of Thailand and the South China Sea: Seasonal Distribution and Species Associations

UC San Diego Naga Report Title Euthecosomatous Pteropods (Mollusca) in the Gulf of Thailand and the South China Sea: Seasonal Distribution and Species Associations Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8dr9f3ht Author Rottman, Marcia Publication Date 1976 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California NAGA REPORT Volume 4, Part 6 Scientific Results of Marine Investigations of the South China Sea and the Gulf of Thailand 1959-1961 Sponsored by South Viet Nam, Thailand and the United States of America Euthecosomatous Pteropods (Mollusca) in the Gulf of Thailand and the South China Sea: Seasonal Distribution and Species Associations By Marcia Rottman The University of California Scripps Institution of Oceanography La Jolla, California 1976 EDITORS: EDWARD BRINTON, WILLIAM A. NEWMAN ASSISTANT EDITORS: NANCE F. NORTH, ANNIE TOWNSEND The Naga Expedition was supported by the International Cooperation Administration ICAc-1085. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 74-620124 ERRATA NAGA REPORT Volume 4, Part 6 EUTHECOSOMATOUS PTEROPODS (MOLLUSCA) IN THE GULF OF THAILAND AND THE SOUTH CHINA SEA: SEASONAL DISTRIBUTION AND SPECIES ASSOCIATIONS By Marcia Rottman page 12, 3rd paragraph, line 10, S-3 should read S-8 page 26, 1st paragraph, line 2, clava (fig. 26a)., should read (Fig. 27). page 60-61, Figure 26 a, b was inadvertently included. The pteropod identified as Creseis virgula clava was subsequently recognized which is combined with that of Creseis chierchiae in Figure 25 a, b. 3 EUTHECOSOMATOUS PTEROPODS (MOLLUSCA) IN THE GULF OF THAILAND AND THE SOUTH CHINA SEA: SEASONAL DISTRIBUTION AND SPECIES ASSOCIATIONS by MARCIA ROTTMAN∗ ∗ Department of Geological Sciences, University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado 80309 4 CONTENTS Page Abstract 5 Introduction and Acknowledgements 6 Section I.