Post-Humanist Interventions: Ethical and Political Challenges to Neoliberalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

00A Inside Cover CC

Access Provided by University of Manchester at 08/14/11 9:17PM GMT 05 Thoburn_CC #78 7/15/2011 10:59 Page 119 TO CONQUER THE ANONYMOUS AUTHORSHIP AND MYTH IN THE WU MING FOUNDATION Nicholas Thoburn It is said that Mao never forgave Khrushchev for his 1956 “Secret Speech” on the crimes of the Stalin era (Li, 115–16). Of the aspects of the speech that were damaging to Mao, the most troubling was no doubt Khrushchev’s attack on the “cult of personality” (7), not only in Stalin’s example, but in principle, as a “perversion” of Marxism. As Alain Badiou has remarked, the cult of personality was something of an “invariant feature of communist states and parties,” one that was brought to a point of “paroxysm” in China’s Cultural Revolution (505). It should hence not surprise us that Mao responded in 1958 with a defense of the axiom as properly communist. In delineating “correct” and “incorrect” kinds of personality cult, Mao insisted: “The ques- tion at issue is not whether or not there should be a cult of the indi- vidual, but rather whether or not the individual concerned represents the truth. If he does, then he should be revered” (99–100). Not unex- pectedly, Marx, Engels, Lenin, and “the correct side of Stalin” are Mao’s given examples of leaders that should be “revere[d] for ever” (38). Marx himself, however, was somewhat hostile to such practice, a point Khrushchev sought to stress in quoting from Marx’s November 1877 letter to Wilhelm Blos: “From my antipathy to any cult of the individ - ual, I never made public during the existence of the International the numerous addresses from various countries which recognized my merits and which annoyed me. -

Empire, Or Multitude Transnational Negri

Empire, or multitude Transnational Negri John Kraniauskas With the publication of Empire,* the oeuvre of the the authors offer us ʻnothing less than a rewriting Italian political philosopher and critic Antonio Negri of The Communist Manifesto for our timeʼ which – until recently an intellectual presence confined to ʻring[s] the death-bell not only for the complacent the margins of Anglo-American libertarian Marxist liberal advocates of the “end of history”, but also for thought – has been transported into what is fast pseudo-radical Cultural Studies which avoid the full becoming an established and influential domain of confrontation with todayʼs capitalismʼ. One effect of transnational cultural theory and criticism. Michael such praise, however, is that Empire is freighted with Hardtʼs mediating role, as translator of key texts by the difficult task of having to live up to itself, as its Negri and other radical Italian intellectuals (such as eulogists have portrayed it. Paulo Virno), and now as co-author of Empire itself, There is some truth in the words (become advertising) has been crucial over the years in helping to establish of these critics. On the one hand, Empire is indeed a and maintain his reputation. Published by Harvard grand work of synthesis, but a synthesis primarily of University Press, the book comes to us with the stamp the work of Negri himself. Over approximately thirty of approval of important contemporary critics – politi- years of writing, much of it spent in prison and exile, cal philosopher Étienne Balibar, subalternist historian Negri has creatively engaged with: transformations in Dipesh Chakrabarty, Marxist cultural critic Fredric the forms of capital accumulation, class recomposition Jameson, urban sociologist Saskia Sassen, Slovenian and working class ʻself-valorizationʼ; the writings of critic-at-large Slavoj Žižek and novelist Leslie Marmon Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Silko – whose words dazzle the potential reader from amongst others; and the political philosophy of Spinoza the bookʼs dust jacket. -

Maurizio Lazzarato. Governing by Debt. Trans. JD Jordan. Los Angeles

Maurizio Lazzarato. Governing by Debt. Trans. J. D. Jordan. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2013. Pp. 280. Maurizio Lazzarato. Signs and Machines: Capitalism and the Production of Subjectivity. Trans. J.D. Jordan. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2014. Pp. 280 Maurizio Lazzarato is an Italian sociologist and philosopher who lives and works in France. He collaborated on collective works with important figures like Antonio Negri and Yann Moulier-Boutang in the 1990s and has been a frequent contributor to the journal Multitudes in which the same two intellectuals were also leading voices. During the same period, he was closely involved as a theorist and activist in the long and inventive struggle of the intermittents du spectacle, French cultural workers defending a social security regime that took particular account of their unstable employment and the way in which their creativity overflowed their periods of paid activity. This involvement fed into a broader reflection and theorization around mutations of labor, the rise of precariousness, neo-liberal governance and leftist mobilization that found expression in a range of texts published in the 2000s. Lazzarato came forcefully to public attention in the English-speaking world when his timely, important book on debt, La Fabrique de l’homme endetté, was translated into English as The Making of the Indebted Man in 2013. That book came out of his broader concern with neo-liberal governance and the subjectivities associated with it, but it was tightly focused on debt. The two books to be discussed here return to that larger picture, the prime focus of Governing by Debt being neo-liberal governance and that of Signs and Machines, the production of subjectivity under capitalism. -

Characterising the Anthropocene: Ecological Degradation in Italian Twenty-First Century Literary Writing

Characterising the Anthropocene: Ecological Degradation in Italian Twenty-First Century Literary Writing by Alessandro Macilenti A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Italian Literature. Victoria University of Wellington 2015 Abstract The twenty-first century has witnessed the exacerbation of ecological issues that began to manifest themselves in the mid-twentieth century. It has become increasingly clear that the current environmental crisis poses an unprecedented existential threat to civilization as well as to Homo sapiens itself. Whereas the physical and social sciences have been defining the now inevitable transition to a different (and more inhospitable) Earth, the humanities have yet to assert their role as a transformative force within the context of global environmental change. Turning abstract issues into narrative form, literary writing can increase awareness of environmental issues as well as have a deep emotive influence on its readership. To showcase this type of writing as well as the methodological frameworks that best highlights the social and ethical relevance of such texts alongside their literary value, I have selected the following twenty-first century Italian literary works: Roberto Saviano’s Gomorra, Kai Zen’s Delta blues, Wu Ming’s Previsioni del tempo, Simona Vinci’s Rovina, Giancarlo di Cataldo’s Fuoco!, Laura Pugno’s Sirene, and Alessandra Montrucchio’s E poi la sete, all published between 2006 and 2011. The main goal of this study is to demonstrate how these works offer an invaluable opportunity to communicate meaningfully and accessibly the discomforting truths of global environmental change, including ecomafia, waste trafficking, illegal building, arson, ozone depletion, global warming and the dysfunctional relationship between humanity and the biosphere. -

Generic Instability and Identity in the Contemporary Novel

Generic Instability and Identity in the Contemporary Novel Generic Instability and Identity in the Contemporary Novel Edited by Madelena Gonzalez and Marie-Odile Pittin-Hédon Generic Instability and Identity in the Contemporary Novel, Edited by Madelena Gonzalez and Marie-Odile Pittin-Hédon This book first published 2010 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2010 by Madelena Gonzalez and Marie-Odile Pittin-Hédon and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-1732-5, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-1732-5 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Madelena Gonzalez ................................................................................... vii Chapter One Generic Instability and the Limits of Postcolonial Identity Crossing Borders and Transforming Genres: Alain Robbe-Grillet, Edward Saïd, and Jamaica Kincaid Linda Lang-Peralta ...................................................................................... 2 Reading Nara’s Diary or the Deluding Strategies of the Implied Author in The Rift Marie-Anne Visoi...................................................................................... 11 Contaminated Copies: J.M.Coetzee’s -

Wu Ming 1 Un Viaggio Che Non Promettiamo Breve

EINAUDI WU MING 1 STILE LIBERO BIG «Con ampiezza inusitata e controllata passione, Wu Ming 1 ha scritto un libro EINAUDI che resterà e che tanti dovrebbero leggere, per capire cosa davvero è accaduto STILE LIBERO BIG nella valle e cosa certamente vi accadrà ancora di importante per tutti». Goffredo Fofi UN VIAGGIO CHE NON PROMETTIAMO BREVE «Un libro che unisce, connette, mette insieme, WU MING 1 fa parte del collettivo di narratori «Mentre scrivevo, in Francia avevano rinviato dà a chiunque lo legga, comunque la pensasse Wu Ming. Insieme alla band ha scritto Q, 54, prima di leggerlo, la possibilità di passare Manituana, Altai, L’Armata dei Sonnambuli l’inizio di aprile. Dopo lo sciopero generale dall’altra parte della barricata. e L’invisibile ovunque, usciti per Einaudi del 31 marzo, la lotta sarebbe proseguita Se poi qualcuno, davanti a un’opera tanto ben a partire dal 1999. Come solista è autore anche il 32, il 33, il 34… Ecco quel che argomentata e documentata, decide di restare di New Thing (Einaudi 2004), Cent’anni i denigratori dei No Tav non riuscivano a capire: in buona fede della sua idea è nel suo diritto, a Nordest. Viaggio tra i fantasmi della «guera ma sarebbe interessante sapere come fa». anche i valsusini si erano ripresi il tempo». granda» (Rizzoli 2015) e – con Roberto Daniele Giglioli Santachiara – di Point Lenana (Einaudi 2013). Ha tradotto romanzi di Elmore Leonard In Italia molti comitati e gruppi di cittadini resistono «Uno straordinario libro che consegna e Stephen King. Per le edizioni Alegre dirige a grandi opere dannose, inutili, imposte dall’alto. -

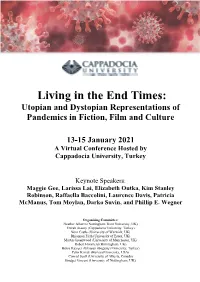

Living in the End Times Programme

Living in the End Times: Utopian and Dystopian Representations of Pandemics in Fiction, Film and Culture 13-15 January 2021 A Virtual Conference Hosted by Cappadocia University, Turkey Keynote Speakers: Maggie Gee, Larissa Lai, Elizabeth Outka, Kim Stanley Robinson, Raffaella Baccolini, Laurence Davis, Patricia McManus, Tom Moylan, Darko Suvin, and Phillip E. Wegner Organising Committee: Heather Alberro (Nottingham Trent University, UK) Emrah Atasoy (Cappadocia University, Turkey) Nora Castle (University of Warwick, UK) Rhiannon Firth (University of Essex, UK) Martin Greenwood (University of Manchester, UK) Robert Horsfield (Birmingham, UK) Burcu Kayışcı Akkoyun (Boğaziçi University, Turkey) Pelin Kıvrak (Harvard University, USA) Conrad Scott (University of Alberta, Canada) Bridget Vincent (University of Nottingham, UK) Contents Conference Schedule 01 Time Zone Cheat Sheets 07 Schedule Overview & Teams/Zoom Links 09 Keynote Speaker Bios 13 Musician Bios 18 Organising Committee 19 Panel Abstracts Day 2 - January 14 Session 1 23 Session 2 35 Session 3 47 Session 4 61 Day 3 - January 15 Session 1 75 Session 2 89 Session 3 103 Session 4 119 Presenter Bios 134 Acknowledgements 176 For continuing updates, visit our conference website: https://tinyurl.com/PandemicImaginaries Conference Schedule Turkish Day 1 - January 13 Time Opening Ceremony 16:00- Welcoming Remarks by Cappadocia University and 17:30 Conference Organizing Committee 17:30- Coffee Break (30 min) 18:00 Keynote Address 1 ‘End Times, New Visions: 18:00- The Literary Aftermath of the Influenza Pandemic’ 19:30 Elizabeth Outka Chair: Sinan Akıllı Meal Break (60 min) & Concert (19:45-20:15) 19:30- Natali Boghossian, mezzo-soprano 20:30 Hans van Beelen, piano Keynote Address 2 20:30- 22:00 Kim Stanley Robinson Chair: Tom Moylan Follow us on Twitter @PImaginaries, and don’t forget to use our conference hashtag #PandemicImaginaries. -

WU MING Is a Collective of Italian Fi Ction Writers, Founded in Bologna in January 2000

WU MING is a collective of Italian fi ction writers, founded in Bologna in January 2000. Its books include the bestselling novel Q, published under the group’s previous pseudonym, Luther Blissett, and the Cold War thriller 54. Praise for Manituana “Th e vivid scenery, well-developed characters and crisp translation are immensely satisfying.” Publishers Weekly “Wu Ming manage to construct stories articulated around the muscular fi bres of history . Manituana is not only a narrative about what could have been, but a cartography of the possible.” Roberto Saviano (author of Gomorrah), L’Espresso “Odd, spirited, tale of educated Indians, savage Europeans and bad mojo in the American outback at the time of the Revolutionary Wa r. Th e Italian fi ction collective known as Wu Ming is back . [with a] worthy treatment of a history too little known.” Kirkus Reviews “Th e novel succeeds in its intention of entertaining the reader with a mass of scenes reconstructed from the shards of history and sustained by a cast of thousands . A novel published in the age of Obama, Manituana provides interesting . insights into the uneasy founding of modern, multiethnic America.” Madeline Clements, Times Literary Supplement “Shaun Whiteside’s streamlined translation allows matters to zip along with gusto. Th ere’s never a dry moment.” Metro “An enlightening . always invigorating read.” Gordon Darroch, Sunday Herald (Glasgow) 4484g.indd84g.indd i 331/03/20101/03/2010 117:26:487:26:48 “Manituana is virtually seamless and the translation is impeccable . It is a quality story that includes characters of depth, a good deal of action, a consistently thoughtful context and thought-provoking concepts.” Ron Jacobs, Counterpunch “Manituana paints a vivid picture of life at the time and suc- cessfully weaves together the culture, traditions and particularly the languages of the Six Nations and the various European settlers living among them. -

The Fever Dream of Documentary a Conversation with Joshua Oppenheimer Author(S): Irene Lusztig Source: Film Quarterly, Vol

The Fever Dream of Documentary A Conversation with Joshua Oppenheimer Author(s): Irene Lusztig Source: Film Quarterly, Vol. 67, No. 2 (Winter 2013), pp. 50-56 Published by: University of California Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/fq.2014.67.2.50 Accessed: 16-05-2017 19:55 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Film Quarterly This content downloaded from 143.117.16.36 on Tue, 16 May 2017 19:55:39 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms THE FEVER DREAM OF DOCUMENTARY: A CONVERSATION WITH JOSHUA OPPENHEIMER Irene Lusztig In the haunting final sequence of Joshua Oppenheimer’s with an elegiac blue light. The camera tracks as she passes early docufiction film, The Entire History of the Louisiana a mirage-like series of burning chairs engulfed in flames. Purchase (1997), his fictional protagonist Mary Anne Ward The scene has a kind of mysterious, poetic force: a woman walks alone at the edge of the ocean, holding her baby in wandering alone in the smoke, the unexplained (and un- a swaddled bundle. -

Download (1541Kb)

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/77618 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. Kate Elizabeth Willman PhD Thesis September 2015 NEW ITALIAN EPIC History, Journalism and the 21st Century ‘Novel’ Italian Studies School of Modern Languages and Cultures University of Warwick 1 ~ TABLE OF CONTENTS ~ Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………………………...... 4 Declaration …………………………………………………………………………………... 5 Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………….... 6 INTRODUCTION ………………………………………………………………………..... 7 - Wu Ming and the New Italian Epic …………………………………………………. 7 - Postmodern Impegno ……………………………………………………………….. 12 - History and Memory ……………………………………………………………….. 15 - Representing Reality in the Digital Age ………………………………………….... 20 - Structure and Organisation …………………………………………………………. 25 CHAPTER ONE ‘Nelle lettere italiane sta accadendo qualcosa’: The Memorandum on the New Italian Epic ……………………………………………………………………..... 32 - New ………………………………………………………………………………… 36 - Italian ……………………………………………………………………………….. 50 - Epic …………………………………………………………………………………. 60 CHAPTER TWO Periodisation ………………………………………………………….. 73 - 1993 ………………………………………………………………………………… 74 - 2001 ........................................................................................................................... -

A-Signifying Communication in Lazzarato and Preciado1 Crítica E Contágio: Comunicação Assignificante Em Lazzarato E Preciado

181 Criticism and contagion: a-signifying communication in Lazzarato and Preciado1 Crítica e contágio: comunicação assignificante em Lazzarato e Preciado DEMÉTRIO ROCHA PEREIRAa Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Post-Graduate Program in Communication. Porto Alegre – RS, Brasil ALEXANDRE ROCHA DA SILVAb Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Post-Graduate Program in Communication. Porto Alegre – RS, Brasil ABSTRACT This article addresses the distinction between signifying and asignifying semiotics, conceived by Félix Guattari and continued by Maurizio Lazzarato in the scope of a 1 This work was supported by CNPq and Capes. critique of contemporary modes of capitalist production. For Lazzarato, investigating a PhD student of the the significant level is not only insufficient, but it helps to conceal the machinic Communication and effectiveness of the asignifying level. By recognizing this as an epistemological problem, Information Program at the Universidade Federal do Rio we discuss the significance of considering articulations between these levels so that Grande do Sul (UFRGS). Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000- the asignifying becomes intelligible. Thus, we suggest that the experimental attitude 0003-0762-8469. E-mail: of Paul B. Preciado provides a useful route for the investigation and translation of [email protected] specific asignifying operations. b Professor of the Graduate Program in Communication Keywords: Asignifying semiotics, Lazzarato, Preciado, communication at the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS). CNPQ Productivity Scholarship RESUMO Holder. Postdoctoral fellow Este artigo aborda a distinção entre semiologia significante e semiótica assignificante, with CNPq scholarship. Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0002- concebida por Félix Guattari e retomada por Maurizio Lazzarato no escopo de uma 1194-6438. -

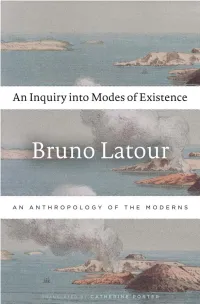

An Inquiry Into Modes of Existence

An Inquiry into Modes of Existence An Inquiry into Modes of Existence An Anthropology of the Moderns · bruno latour · Translated by Catherine Porter Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England 2013 Copyright © 2013 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America The book was originally published as Enquête sur les modes d'existence: Une anthropologie des Modernes, copyright © Éditions La Découverte, Paris, 2012. The research has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (fp7/2007-2013) erc Grant ‘ideas’ 2010 n° 269567 Typesetting and layout: Donato Ricci This book was set in: Novel Mono Pro; Novel Sans Pro; Novel Pro (christoph dunst | büro dunst) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Latour, Bruno. [Enquête sur les modes d'existence. English] An inquiry into modes of existence : an anthropology of the moderns / Bruno Latour ; translated by Catherine Porter. pages cm “The book was originally published as Enquête sur les modes d'existence : une anthropologie des Modernes.” isbn 978-0-674-72499-0 (alk. paper) 1. Civilization, Modern—Philosophy. 2. Philosophical anthropology. I. Title. cb358.l27813 2013 128—dc23 2012050894 “Si scires donum Dei.” ·Contents· • To the Reader: User’s Manual for the Ongoing Collective Inquiry . .xix Acknowledgments . xxiii Overview . xxv • ·Introduction· Trusting Institutions Again? . 1 A shocking question addressed to a climatologist (02) that obliges us to distinguish values from the ac- counts practitioners give of them (06). Between modernizing and ecologizing, we have to choose (08) by proposing a different system of coordinates (10).