The Strength of the Mamas: Creating and Living in a World of Wonder, Dignity, and Freedom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Devils' Dance

THE DEVILS’ DANCE TRANSLATED BY THE DEVILS’ DANCE HAMID ISMAILOV DONALD RAYFIELD TILTED AXIS PRESS POEMS TRANSLATED BY JOHN FARNDON The Devils’ Dance جينلر بازمي The jinn (often spelled djinn) are demonic creatures (the word means ‘hidden from the senses’), imagined by the Arabs to exist long before the emergence of Islam, as a supernatural pre-human race which still interferes with, and sometimes destroys human lives, although magicians and fortunate adventurers, such as Aladdin, may be able to control them. Together with angels and humans, the jinn are the sapient creatures of the world. The jinn entered Iranian mythology (they may even stem from Old Iranian jaini, wicked female demons, or Aramaic ginaye, who were degraded pagan gods). In any case, the jinn enthralled Uzbek imagination. In the 1930s, Stalin’s secret police, inveigling, torturing and then executing Uzbekistan’s writers and scholars, seemed to their victims to be the latest incarnation of the jinn. The word bazm, however, has different origins: an old Iranian word, found in pre-Islamic Manichaean texts, and even in what little we know of the language of the Parthians, it originally meant ‘a meal’. Then it expanded to ‘festivities’, and now, in Iran, Pakistan and Uzbekistan, it implies a riotous party with food, drink, song, poetry and, above all, dance, as unfettered and enjoyable as Islam permits. I buried inside me the spark of love, Deep in the canyons of my brain. Yet the spark burned fiercely on And inflicted endless pain. When I heard ‘Be happy’ in calls to prayer It struck me as an evil lure. -

AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL ANNUAL REPORT 2014–2015 the Record Crowd Disperses After the 2015 Anzac Day Dawn Service

AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL ANNUAL REPORT 2014–2015 AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL WAR AUSTRALIAN ANNUAL REPORT 2014–2015 REPORT ANNUAL The record crowd disperses after the 2015 Anzac Day Dawn Service. AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIALMEMORIAL ANNUAL REPORT 2014–2012014–20155 Annual report for the year ended 30 June 2015, together with the financial statements and the report of the Auditor-General Images produced courtesy of the Australian War Memorial, Canberra Cover and title page images Reverse and obverse: One of the first community monuments to be completed after the Great War, Gilbert Doble’s Winged victory is prominently placed in the legacies section of the redeveloped First World War Galleries. ART96224 Copyright © Australian War Memorial ISSN 1441 4198 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced, copied, scanned, stored in a retrieval system, recorded, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher. Australian War Memorial GPO Box 345 Canberra, ACT 2601 Australia www.awm.gov.au ii | AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL ANNUAL REPORT 2014–2015 Private G.J. Giles’s tunic, encrusted with mud from the Somme, has long been an iconic object, and is currently on display in the First World War Galleries. RELAWM04500 AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL ANNUAL REPORT 2014–2015 | iii iv | AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL ANNUAL REPORT 2014–2015 AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL ANNUAL REPORT 2014–2015 | v His Royal Highness Prince Henry of Wales is welcomed by Rear Admiral Ken Doolan AO RAN (Retd), Chairman of the Council of the Australian War Memorial. -

Rapture of the Nerds

coerced purchase of our humble article of commerce. USA: Amazon Kindle (DRM-free) Barnes and Noble Nook (DRM-free) Google Books (DRM-free) Kobo (DRM-free) Apple iBooks (DRM-free) Amazon Booksense (will locate a store near you!) Barnes and Noble Powells Booksamillion UK: Forbidden Planet Waterstones Amazon Rapture of the Nerds Canada: by Cory Doctorow and Charles Stross Amazon Kindle (DRM-free) Kobo (DRM-free) Chapters/Indigo Amazon.ca A COMMERCIAL INTERLUDE Gondar primulon, Earthling! Welcome to the free READ THIS FIRST CC-licensed ebook! We know that there's no way This book is distributed under a Creative we could keep you from getting a free copy of this Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs from some dodgy corner of the Internet. Rather 3.0 license. That means: than send you off to the kind of site you'd better visit through a proxy with your cookies turned off, You are free: we're giving you this-here free, pristine, hand- to Share—to copy, distribute and transmit crafted ebook in a variety of formats. We hope you the work enjoy reading it as much as we enjoyed writing it (though, truth be told, we really enjoyed writing Under the following conditions: it). And we hope that, having read it, you rush Attribution. You must attribute the work in straight out to your local bookseller and buy a the manner specified by the author or copy—or, if you prefer to buy the ebook or have licensor (but not in any way that suggests the smashing and lovely physical book delivered that they endorse you or your use of the to you, here are some links that will let you reward work). -

Chapter 1: Introduction to the Study

CHARACTERISTICS OF PSYCHOTHERAPISTS WHO ARE PASSIONATELY COMMITTED TO PUBLIC MENTAL HEALTH By Brian Miller A Dissertation Submitted to Case Western Reserve University In Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Mandel School of Applied Social Sciences August, 2005 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the dissertation of Brian Miller Candidate for the Ph.D. degree*. (signed) Wally Gingerich, Ph.D. (chair of the committee) Jerry Floersch, Ph.D. Kathy Farkas, Ph.D. Mary Anthony, Ph.D. (date) May 26, 2005 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgments………………………………………………………………………… 5 Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………7 Chapter I: Introduction…………………………………………………………………….9 Chapter II: Review of the Literature………………………………………………………18 The Definition and Nature of Burnout·············································································19 Associations of Work/Environmental Characteristics and Burnout in Mental Health Professionals··························································································································22 Associations of Personal Characteristics and Burnout in Social Service Workers/ Therapists································································································································23 Moderating Variables············································································································24 -

Oral History Interview with Elaine Reichek, 2008 Feb. 12

Oral history interview with Elaine Reichek, 2008 Feb. 12 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Elaine Reichek on February 12, 2008. The interview was conducted by Sarah G. Sharp for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Elaine Reichek and Sarah G. Sharp have reviewed the transcript and have made corrections and emendations. The reader should bear in mind that he or she is reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview SARAH G. SHARP: My name is Sarah Sharp and I’m here with Elaine Reichek doing an oral history interview for the Archives of American Art, for the Smithsonian Institution. Today is February 12, 2008. Elaine, you grew up in Brooklyn, right? ELAINE REICHEK: Yes. MS. SHARP: Yes. MS. REICHEK: Yes. MS. SHARP: Can you just talk a little bit about what your family was like? MS. REICHEK: I grew up in a big Dutch Colonial house with middle class parents in a family of three. I’m the middle child. MS. SHARP: And what part of Brooklyn were you in? MS. REICHEK: Flatbush. MS. SHARP: And did you go to public schools? MS. REICHEK: Yes, I went to public school for primary, junior high school and high school. MS. SHARP: I’m curious what high school was like for you. -

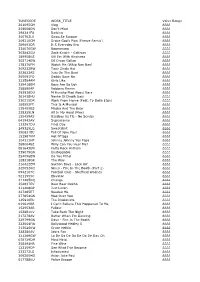

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 261095CM

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 261095CM Vlog ££££ 259008DN Don't Mind ££££ 298241FU Barking ££££ 300703LV Swag Se Swagat ££££ 309210CM Drake God's Plan (Freeze Remix) ££££ 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 234070GW Boomerang ££££ 302842GU Zack Knight - Galtiyan ££££ 189958KS Kill Em With Kindness ££££ 302714EW Dil Diyan Gallan ££££ 178176FM Watch Me (Whip Nae Nae) ££££ 309232BW Tiger Zinda Hai ££££ 253823AS Juju On The Beat ££££ 265091FQ Daddy Says No ££££ 232584AM Girls Like ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 258890AP Robbery Remix ££££ 292938DU M Huncho Mad About Bars ££££ 261438HU Nashe Si Chadh Gayi ££££ 230215DR Work From Home (Feat. Ty Dolla $Ign) ££££ 188552FT This Is A Musical ££££ 135455BS Masha And The Bear ££££ 238329LN All In My Head (Flex) ££££ 155459AS Bassboy Vs Tlc - No Scrubs ££££ 041942AV Supernanny ££££ 133267DU Final Day ££££ 249325LQ Sweatshirt ££££ 290631EU Fall Of Jake Paul ££££ 153987KM Hot N*Gga ££££ 304111HP Johnny Johnny Yes Papa ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 081643EN Party Rock Anthem ££££ 239079GN Unstoppable ££££ 254096EW Do You Mind ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 216422EM Section Boyz - Lock Arf ££££ 325052KQ Nines - Fire In The Booth (Part 2) ££££ 0942107C Football Club - Sheffield Wednes ££££ 5211555C Elevator ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 254637EV Baar Baar Dekho ££££ 311408GP Just Listen ££££ 227485ET Needed Me ££££ 277854GN Mad Over You ££££ 125910EU The Illusionists ££££ 019619BR I Can't Believe This Happened To Me ££££ 152953AR Fallout ££££ 153881KV Take Back The Night ££££ 217278AV Better When -

List by Song Title

Song Title Artists 4 AM Goapele 73 Jennifer Hanson 1969 Keith Stegall 1985 Bowling For Soup 1999 Prince 3121 Prince 6-8-12 Brian McKnight #1 *** Nelly #1 Dee Jay Goody Goody #1 Fun Frankie J (Anesthesia) - Pulling Teeth Metallica (Another Song) All Over Again Justin Timberlake (At) The End (Of The Rainbow) Earl Grant (Baby) Hully Gully Olympics (The) (Da Le) Taleo Santana (Da Le) Yaleo Santana (Do The) Push And Pull, Part 1 Rufus Thomas (Don't Fear) The Reaper Blue Oyster Cult (Every Time I Turn Around) Back In Love Again L.T.D. (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Brandy (Get Your Kicks On) Route 66 Nat King Cole (Ghost) Riders In The Sky Johnny Cash (Goin') Wild For You Baby Bonnie Raitt (Hey Won't You Play) Another Somebody Done Somebody WrongB.J. Thomas Song (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Otis Redding (I Don't Know Why) But I Do Clarence "Frogman" Henry (I Got) A Good 'Un John Lee Hooker (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace (I Just Want It) To Be Over Keyshia Cole (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew (The) (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew (The) (I Know) I'm Losing You Temptations (The) (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons ** Sam Cooke (If Only Life Could Be Like) Hollywood Killian Wells (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Shania Twain (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here! ** Shania Twain (I'm A) Stand By My Woman Man Ronnie Milsap (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkeys (The) (I'm Settin') Fancy Free Oak Ridge Boys (The) (It Must Have Been Ol') Santa Claus Harry Connick, Jr. -

West Papua in WW2, Ross Himona

SCRIPT 1 Ladies & Gentlemen. Good afternoon. This exhibition is about the war against the Japanese in West Papua, or as it was then, Netherlands Nieuw Guinea, or Dutch New Guinea. It was of course just part of the War in the Pacific. This presentation aims to put the West Papua Exhibition in context. Firstly, historically. Secondly, in the context of the whole War in the Pacific against the Japanese from 1941 to 1945. And finally, in relation to the better known part of that War and Australia’s role in it / the War in Australia’s territory of Papua New Guinea. What and where is West Papua? The next four slides are maps showing a very brief history of New Guinea. 2 Prior to WW1 the Netherlands, Germany and Britain were the colonial powers in New Guinea. Territory of Papua (Red). In 1883, the Colony of Queensland tried to annex the southern half of eastern New Guinea, but the British government did not approve. However, when Germany began settlements in the north a British protectorate was proclaimed in 1884 over the southern coast of New Guinea and its adjacent islands. The protectorate, called British New Guinea, was annexed outright on 4 September 1888. The possession was placed under the authority of the Commonwealth of Australia in 1902, following Federation. Following the passage of the Papua Act in 1905, British New Guinea became the Territory of Papua, formal Australian administration began in 1906, and Papua remained under Australian control until the independence of Papua New Guinea in 1975. German New Guinea(Black) (German: Deutsch-Neuguinea) was the first part of the German colonial empire. -

Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), 2009-09-23

WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 23, 2009 SPORTS Dual talk By MARLEEN LINARES [email protected] The director of the UI’s Hurt lockers Dual Career Network, Iowa head coach Kirk Ferentz received an e-mail last March says Bryan Bulaga, Tony from somewhere unexpected: Tübingen, Germany. Moeaki, and Derrell Johnson- Koulianos are still day-to-day Waiting in Joan Murrin’s and are likely out for the inbox was an invitation Hawkeyes’ game against Penn from the German American State this weekend. 12 Institute there to be a keynote speaker at a con- ference on dual-career Badger hunting issues in Germany.The U.S. Embassy in Germany fund- The Iowa volleyball team ed her trip. begins its conference slate on Universities throughout the road tonight against JULIE KOEHN/THE DAILY IOWAN Germany are trying to Wisconsin on the Big Ten either set up or upgrade Network. 12 UI research scientist Tim Barrett demonstrates how he examines paper from a book dating to the 1400s, using nondestructive instruments in the vault of the Special Collections area in the UI Main Library Tuesday. Barrett has been honored with a $500,000 grant from the their dual-career programs, MacArthur Foundation. which helps spouses of NEWS newly hired faculty and staff find nearby employment. Old becomes new The German American Institute at Tübingen invit- Coralville mulls revamp of “Old UI’s Barrett wins MacArthur ed Murrin based on the UI’s Town Coralville.” 2 advanced program. The UI By SAMANTHA HONKEN of his research regarding MacArthur Foundation grant recipients Dual Career Network, [email protected] the use of gelatin in 15th- established in 1994, has Feed the students century paper. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 104 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 104 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 142 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, MARCH 12, 1996 No. 33 House of Representatives The House met at 12:30 p.m. and was derstand the reasons behind an effort seems a step below territory. Wake Is- called to order by the Speaker pro tem- to change the status. An unincor- land is a possession and has no govern- pore [Mr. KOLBE]. porated territory is little more than a ment functioning there. It is managed f colony with a legal title which dis- by a Federal agency. guises it. An unincorporated territory Guam is an unincorporated territory DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO means that the territory is owned by TEMPORE the United States and that the Con- that is working to establish a new The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- gress has plenary power over it. But it Commonwealth. The Guam Common- fore the House the following commu- is not incorporated meaning that it is wealth Act, H.R. 1056, which I intro- nication from the Speaker: not truly an integral part of the United duced early in the 104th, provides the WASHINGTON, DC, States. framework for this new Common- March 12, 1996. Unincorporated means that the Con- wealth. Governor Gutierrez and the I hereby designate the Honorable JIM stitution is not fully applicable to Guam Commission on Self-Determina- KOLBE to act as Speaker pro tempore on this Guam. Unincorporated means that the tion have been negotiating with the day. -

JB DB by Artist

Song Title …. Artists Drop (Dirty) …. 216 Hey Hey …. 216 Baby Come On …. (+44) When Your Heart Stops Beating …. (+44) 96 Tears …. ? & The Mysterians Rubber Bullets …. 10cc The Things We Do For Love …. 10cc The Things We Do For Love …. 10cc Come See Me …. 112' Cupid …. 112' Damn …. 112' Dance With Me …. 112' God Knows …. 112' I'm Sorry (Interlude) …. 112' Intro …. 112' Just A Little While …. 112' Just A Little While …. 112' Last To Know …. 112' Let This Go …. 112' Let This Go …. 112' Love Me …. 112' My Mistakes …. 112' Nowhere …. 112' Only You …. 112' Peaches & Cream …. 112' Peaches & Cream (Clean) …. 112' Peaches & Cream (Dirty) …. 112' Peaches & Cream (Inst) …. 112' That's How Close We Are …. 112' U Already Know …. 112' U Already Know …. 112' We Goin' Be Alright …. 112' What If …. 112' What The H**l Do You Want …. 112' Why Can't We Get Along …. 112' You Already Know (Clean) …. 112' Dance Wit Me (Remix) …. 112' (w Beanie Segal) It's Over (Remix) …. 112' (w G.Dep & Prodigy) The Way …. 112' (w Jermaine Dupri) Hot & Wet (Dirty) …. 112' (w Ludacris) Love Me …. 112' (w Mase) Only You …. 112' (w Notorious B.I.G.) Anywhere (Remix) …. 112' (w Shyne) If I Can Hit …. 112' (w T.I.) If I Hit …. 112' (w T.I.) Closing The Club …. 112' (w Three 6 Mafia) Dunkie Butt …. 12 Gauge Lie To Me …. 12 Stones 1, 2, 3 Red Light …. 1910 Fruitgum Co. Goody Goody Gumdrops …. 1910 Fruitgum Co. Indian Giver …. 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simple Simon Says …. 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simple Simon Says …. -

Spellweaver : a Novel

Newcomb 1 Spellweaver A novel Cyrus Newcomb A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the University Honors Program University of South Florida, St. Petersburg April 23, 2013 Thesis Director: Jon Wilson, Florida Humanities Council Newcomb 2 University Honors Program University of South Florida St. Petersburg, Florida CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL ___________________________ Honors Thesis ___________________________ This is to certify that the Honors Thesis of Cyrus A. Newcomb has been approved by the Examining Committee on April 23, 2013 as satisfying the thesis requirement of the University Honors Program Examining Committee: ___________________________ Thesis Director: Jon Wilson Florida Humanities Council ____________________________ Thesis Committee Member: Barbra Jolley, Ph.D. Professor, College of Arts and Sciences Newcomb 3 For Sam, The best friend I have never met Newcomb 4 Chapter 1 Cole Travers strode into the Chimera's Tail as if he owned the place, and this upset Stanton Letherben, the man who actually did, more than the usually genial barman cared to admit. After serving on the front lines during the end of the Wars of Annexation, Stanton had purchased the Chimera's Tail with the last part of his meagre soldier's commission. He had been injured during his tour of duty, returning to Thertan with a bum knee, a broken arm, and a face like a squashed gourd. A bit of healing magic had saved Stanton from dying but it had not been able to make him handsome again, and Stanton's betrothed had left him after seeing his scarred and grotesque body. Now, Stanton invested all his time in the Chimera's Tail and took a fierce pride in what he had created.