In Memoriam: Norbert Brainin: Founder and Primarius of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Symposium Programme

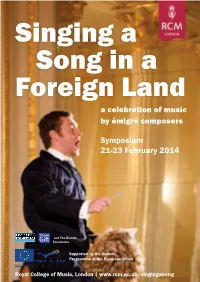

Singing a Song in a Foreign Land a celebration of music by émigré composers Symposium 21-23 February 2014 and The Eranda Foundation Supported by the Culture Programme of the European Union Royal College of Music, London | www.rcm.ac.uk/singingasong Follow the project on the RCM website: www.rcm.ac.uk/singingasong Singing a Song in a Foreign Land: Symposium Schedule FRIDAY 21 FEBRUARY 10.00am Welcome by Colin Lawson, RCM Director Introduction by Norbert Meyn, project curator & Volker Ahmels, coordinator of the EU funded ESTHER project 10.30-11.30am Session 1. Chair: Norbert Meyn (RCM) Singing a Song in a Foreign Land: The cultural impact on Britain of the “Hitler Émigrés” Daniel Snowman (Institute of Historical Research, University of London) 11.30am Tea & Coffee 12.00-1.30pm Session 2. Chair: Amanda Glauert (RCM) From somebody to nobody overnight – Berthold Goldschmidt’s battle for recognition Bernard Keeffe The Shock of Exile: Hans Keller – the re-making of a Viennese musician Alison Garnham (King’s College, London) Keeping Memories Alive: The story of Anita Lasker-Wallfisch and Peter Wallfisch Volker Ahmels (Festival Verfemte Musik Schwerin) talks to Anita Lasker-Wallfisch 1.30pm Lunch 2.30-4.00pm Session 3. Chair: Daniel Snowman Xenophobia and protectionism: attitudes to the arrival of Austro-German refugee musicians in the UK during the 1930s Erik Levi (Royal Holloway) Elena Gerhardt (1883-1961) – the extraordinary emigration of the Lieder-singer from Leipzig Jutta Raab Hansen “Productive as I never was before”: Robert Kahn in England Steffen Fahl 4.00pm Tea & Coffee 4.30-5.30pm Session 4. -

The Amadeus Quartet

The Uuive ·cal Society The Presents The Amadeus Quartet NORBERT BRAININ, Violinist PETER SCHIDLOF, Violist SIEGMUND NISSEL, Violinist MARTIN LOVETT, Cellist THURSDAY EVENING, APRIL 6, 1978, AT 8:30 RACKHAM AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM Quartet in B-flat major, K. 458 ("Hunting") MOZART Allegro vivace assai Menuetto: moderato Adagio Allegro assai Quartet No.2 in C major, Op. 36 BRITTEN Allegro colmo senza rigore Vivace Chacony: sostenuto, molto piu andante, molto piu adagio INTERMISSION Quartet in F major, Op. 96 ("American") DVORAK Allegro rna non troppo Lento Molto vivace Vivace rna non troppo Deutsche Grammophon, Angel, and Westminster Records. Watch for alLnlJ"ltliCement next week of the new 1978-1979 Chamber Arts Series, part of next season's International Presentations marking the 100th year of the University Musical Society. Eighth Concert Fifteenth Annual Chamber Arts Series Complete Programs 4121 About the Artists England's internationally famous Amadeus Quartet has become one of America's favorite chamber music ensembles since its United States debut in 1952. Although their home base is in London, only one member of the Quartet, Martin Lovett, is a native Englishman. His colleagues, Norbert Brainin, Siegmund Nissel, and Peter Schidlof, are Austrian-born and received their early training in Vienna. To escape the oppressive Nazi regime, the families moved to England in 1938. In spite of such parallel events, they did not meet until 1941 when all four boys, employed in various war factories, were pursuing their music studies under Max Rostal. Thus began the association which led to the iormation of a permanent quartet, with their first public appearance in 1948. -

Annual Brochure 2016

· 2016 · www.ecma-music.com www.ecma-music.com EUROPEAN CHAMBER MUSIC ACADEMY Oslo 2015 Vilnius 2015 Großraming 2016 contents 04 Preface Bern 2015 Fiesole 2015 08 Erasmus+ 10 ECma – Educational program 12 Partnerships 14 Partners 23 Cooperating partners 24 STaTEmEnTs about ECma i 26 Ensembles 29 Alumni 30 Guest Ensembles 31 Awards and achievements Vienna/Grafenegg 2015 41 General assembly, 2015 42 STaTEmEnTs about ECma ii Oslo 2016 44 Tutors 49 Cd releases Manchester 2016 50 Obituary – peter Cropper 52 Events Vilnius 2016 54 The association as of october 2016 EuropEan ChambEr musiC aCadEmy 3 PREFACE – ThE STORY OF ECMA t was piero Farulli who had the original idea and subsequently asked potential how to search for and find their own inter pre tations. The expansion his good friends hatto beyerle (alban berg Quartet), Norbert brainin from string quartets to ensembles with piano or other instruments was a i (amadeus Quartet), and milan skampa (smetana Quartet) to head the natural consequence. first accademia Europea del Quartetto with him in Fiesole. This course, held during 2001 and 2002, was an extraordinary success for the young Today, following more than ten years of excellent work and out standing participants: the incredible experience of spending one week with four great success under the leadership of its two artistic directors, ECma has come artists and masters, each of them so different from the others, was utterly to be regarded as an apex of chamber music training. and a continuously unlike any of the master classes in which they had participated before! increasing number of institutions, academies, and festivals have come to view ECma as an anchor point: not as a standalone school, but as a strate- so piero asked hatto to take the lead and fashion a true programme of ad- gic partnership of institutions, each of which makes its own contribution in vanced training for chamber musicians that would travel throughout Europe. -

Marshall University Music Department Presents

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar All Performances Performance Collection Fall 11-7-2008 Marshall University Music Department Presents, Music Alive Series, Graffe trS ing Quartet, Štĕpán Graffe, violin, Lukáš Bednařik, violin, Lukáš Cybulski, viola, Michal Hreno, violoncello, with, Michiko Otaki, piano Michiko Otaki Štĕpán Graffe Lukáš Bednařik Lukáš Cybulski Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/music_perf Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Otaki, Michiko; Graffe, Štĕpán; Bednařik, Lukáš; and Cybulski, Lukáš, "Marshall University Music Department Presents, Music Alive Series, Graffe trS ing Quartet, Štĕpán Graffe, violin, Lukáš Bednařik, violin, Lukáš Cybulski, viola, Michal Hreno, violoncello, with, Michiko Otaki, piano" (2008). All Performances. 752. http://mds.marshall.edu/music_perf/752 This Recital is brought to you for free and open access by the Performance Collection at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Performances by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. DEPARTMENT of MUSIC Program String Quartet in g min.or, Franz Joseph Haydn op. 74, no. 3 ("Rider") (1732-1809) Allegro moderate MUSIC Largo assai Menuetto: Allegretto Finale: Allegro con brio presents the Quintet for Piano and Strings Robert Schumann Music Alive Series in E-flat major, op. 44 (1810-1856) Allegro brillante In modo d'una marcia GRAFFE STRING QUARTET Scherzo: Molto vivace Stepan Graffe, violin Allegro ma non troppo Lukas Bednarik, violin Lukas Cybulski, viola Michiko Otaki, piano Michal Hreno, violoncello with Michiko Otaki, piano Friday, November 7, 2008 Exclusive Management for the First Presbyterian Church GRAFFE QUARTET and MICHIKO OTAKI: 12:00 p.m. -

View PDF Online

MARLBORO MUSIC 60th AnniversAry reflections on MA rlboro Music 85316_Watkins.indd 1 6/24/11 12:45 PM 60th ANNIVERSARY 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC Richard Goode & Mitsuko Uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 2 6/23/11 10:24 AM 60th AnniversA ry 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC richard Goode & Mitsuko uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 3 6/23/11 9:48 AM On a VermOnt HilltOp, a Dream is BOrn Audience outside Dining Hall, 1950s. It was his dream to create a summer musical community where artists—the established and the aspiring— could come together, away from the pressures of their normal professional lives, to exchange ideas, explore iolinist Adolf Busch, who had a thriving music together, and share meals and life experiences as career in Europe as a soloist and chamber music a large musical family. Busch died the following year, Vartist, was one of the few non-Jewish musicians but Serkin, who served as Artistic Director and guiding who spoke out against Hitler. He had left his native spirit until his death in 1991, realized that dream and Germany for Switzerland in 1927, and later, with the created the standards, structure, and environment that outbreak of World War II, moved to the United States. remain his legacy. He eventually settled in Vermont where, together with his son-in-law Rudolf Serkin, his brother Herman Marlboro continues to thrive under the leadership Busch, and the great French flutist Marcel Moyse— of Mitsuko Uchida and Richard Goode, Co-Artistic and Moyse’s son Louis, and daughter-in-law Blanche— Directors for the last 12 years, remaining true to Busch founded the Marlboro Music School & Festival its core ideals while incorporating their fresh ideas in 1951. -

Emigremusicianspdf.Pdf

Short biographies and sources for further information About the sources: Extensive biographies and information about compositions, recordings, careers and families of émigré musicians can be found in German in the excellent LexM online encyclopedia of musicians persecuted by the Nazis, hosted by the University of Hamburg. English-language information about many émigrés can be found on Wikipedia. I am indebted for many details to Jutta Raab Hansen, author of NS-verfolgte Musiker in England (Hamburg: Bockel Verlag, 1996), who interviewed many émigré musicians in London during the 1990s and published nearly 300 short biographies in her book. Norbert Meyn Bing, Rudolf Born 9.1.1902 in Vienna, died 2.9.1997 in New York From 1928 opera manager Darmstadt, then Städtische Oper Berlin 1930-33 Emigration to UK in 1934 1936-1949 general manager of Glyndebourne opera Founding director of the Edinburgh Festival 1947 General manager of Metropolitain Opera New York 1950-1972 Raab Hansen, p. 397 Brainin, Norbert Born 12.3.1923 in Vienna, died April 10, 2005 in London Emigration to UK in 1938 Violin studies with Carl Flesch and Max Rostal in London 1940 internment Isle of Man concerts with Ferdinand Rauter and Paul Hamburger Work as a metal worker duringt he war 1948-1987 1st violin in Amadeus Quartet with Sigmund Nissel, Peter Schidlof (both also émigrés) and Marin Lovett, over 4000 concerts http://www.lexm.uni-hamburg.de/object/lexm_lexmperson_00002549 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l06wDJIjQ2M Raab Hansen, p. 399 Busch, Fritz Born 13.3.1890 in Siegen, died 14.9.1951 in London Started as opera conductor in Riga, Aachen and Stuttgart 1922-1934 music director of Dresden Opera Nazi persecution for political reasons, Busch was not Jewish 1934-1939 music director of Glyndebourne Festival Opera, international conducting career, Teatro Colon Buenos Aires, Metropolitain Opera New York, Chicago, Copenhagen, Stockholm http://www.lexm.uni-hamburg.de/object/lexm_lexmperson_00001742 Raab Hansen, p. -

Norbert Brainin, Primarius of the Amadeus Quartet

Click here for Full Issue of Fidelio Volume 14, Number 1-2, Spring-Summer 2005 Norbert Brainin: Founder and Primarius of the Amadeus Quartet he death of violinist Norbert exactly the kind of violin playing TBrainin on April 10, 2005, which you need in order to play came as a shock, and is still Beethoven’s music,” said Brainin. difficult to grasp. He died at the “It means, producing a certain age of 82 in London. With him the singing tone. It’s like the bel canto world loses one of those truly great technique in singing. And, like a artists and human beings, who, singer, you have to rehearse this because of their moral integrity every day. Every day.” Yet, aside and extraordinary charisma, are from all the talent and able to shape an entire epoch, since industriousness, as well as the they are able to successfully enthusiasm and joy in doing mediate in all cultures precisely creative work, the cultural and that which makes man unique: the personal background of the joy in creative work. Anyone who members of the Amadeus Quartet has seen firsthand only once, how was also a decisive reason for its intensively, precisely, and success, and for that the career of rigorously—but never ever Norbert Brainin is exemplary. pedantically, always inspiring, EIRNS loose, and with a lot of jokes— The Development of a Great Norbert Brainin was capable of Musician teaching especially young IN MEMORIAM Born in 1923 in Vienna, Brainin’s musicians, how great Classical enthusiasm and talent for playing works are to be performed, so that the violin became clear already at the listeners can be reached and 2004—an interview which now the age of 6, when he saw the 12-year- ennobled in the best Schillerian sense, unfortunately has become the very last old prodigy Yehudi Menuhin perform understands the deeper meaning of of his life. -

Digital Booklet Porgy & Bess

71 TRACKS THE AMADEUS QUARtet ReCORDINGS VOL. I BEETHOVEN Berlin, 1950-1967 recording producer: Wolfgang Gottschalk (Op. 127) Hartung (Op. 59, 2) Hermann Reuschel (Op. 18, 2-5 / Op. 59, 1 / Op. 130-133 / Op. 135 / Op. 29) Salomon (Op. 18, 1+6 / Op. 59, 3 / Op. 95) recording engineer: Siegbert Bienert (Op. 18, 5 / Op. 130-133 / Op. 29) Peter Burkowitz (Op. 18, 6) THE Heinz Opitz (Op. 18, 2 / Op. 59, 1+2 / Op. 127 / Op. 135) Preuss (Op. 18, 1 / Op. 59, 3 / Op. 95) Alfred Steinke (Op. 18, 3+4) AMADEUS QUARtet ReCORDinGS Berlin, 1950-1967 Eine Aufnahme von RIAS Berlin (lizenziert durch Deutschlandradio) recording: P 1950 - 1967 Deutschlandradio research: Rüdiger Albrecht remastering: P 2013 Ludger Böckenhoff rights: audite claims all rights arising from copyright law and competition law in relation to research, compilation and re-mastering of the original audio tapes, VOL. I BEETHOVEN as well as the publication of this CD. Violations will be prosecuted. The historical publications at audite are based, without exception, on the original tapes from broadcasting archives. In general these are the original analogue tapes, MstASTER RELEASE which attain an astonishingly high quality, even measured by today’s standards, with their tape speed of up to 76 cm/sec. The remastering – professionally com- petent and sensitively applied – also uncovers previously hidden details of the interpretations. Thus, a sound of superior quality results. CD publications based 1 on private recordings from broadcasts cannot be compared with these. AMADEUS-QUARtett further reading: Daniel Snowman: The Amadeus Quartet. The Men and the Music, violin I Norbert Brainin Robson Books (London, 1981) violin II Siegmund Nissel Gerd Indorf: Beethovens Streichquartette, Rombach Verlag (Freiburg i. -

Musique Et Camps De Concentration

Colloque « MusiqueColloque et « campsMusique de concentration »et camps de Conseilconcentration de l’Europe - 7 et 8 novembre » 2013 dans le cadre du programme « Transmission de la mémoire de l’Holocauste et prévention des crimes contre l’humanité » Conseil de l’Europe - 7 et 8 novembre 2013 Éditions du Forum Voix Etouffées en partenariat avec le Conseil de l’Europe 1 Musique et camps de concentration Éditeur : Amaury du Closel Co-éditeur : Conseil de l’Europe Contributeurs : Amaury du Closel Francesco Lotoro Dr. Milijana Pavlovic Dr. Katarzyna Naliwajek-Mazurek Ronald Leopoldi Dr. Suzanne Snizek Dr. Inna Klause Daniel Elphick Dr. David Fligg Dr. h.c. Philippe Olivier Lloica Czackis Dr. Edward Hafer Jory Debenham Dr. Katia Chornik Les vues exprimées dans cet ouvrage sont de la responsabilité des auteurs et ne reflètent pas nécessairement la ligne officielle du Conseil de l’Europe. 2 Sommaire Amaury du Closel : Introduction 4 Francesco Lotoro : Searching for Lost Music 6 Dr Milijana Pavlovic : Alma Rosé and the Lagerkapelle Auschwitz 22 Dr Katarzyna Naliwajek–Mazurek : Music within the Nazi Genocide System in Occupied Poland: Facts and Testimonies 38 Ronald Leopoldi : Hermann Leopoldi et l’Hymne de Buchenwald 49 Dr Suzanne Snizek : Interned musicians 53 Dr Inna Klause : Musicocultural Behaviour of Gulag prisoners from the 1920s to 1950s 74 Daniel Elphick : Mieczyslaw Weinberg: Lines that have escaped destruction 97 Dr David Fligg : Positioning Gideon Klein 114 Dr. h.c. Philippe Olivier : La vie musicale dans le Ghetto de Vilne : un essai -

AJR Journal | July 2020

VOLUME 20 NO.7 JULY 2020 JOURNAL The Association of Jewish Refugees ROUTES TO Fleeing from France FREEDOM France makes our headlines twice 2020 is an extraordinary year for anniversaries. The 75th this month, and not just because we still can’t travel there. Our lead story anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz in January, the 75th focuses on the huge wave of refugees anniversary of VE-Day in May, and, a few days ago, the 80th from France while an article on page 9 looks at the kindertransports that left anniversary of the Fall of France. France for the United States. Other articles are based on recent online events hosted by the AJR, and on some fascinating stories about the late relatives of some of our members. We hope you enjoy this issue and that you are staying well and enjoying the little bit more freedom that is gradually being afforded to us as lockdown slowly eases. News ....................................................3 & 20 Born to Care ................................................. 4 Letter from Israel .......................................... 5 Marc Chagall, Marcel Duchamp, Claude Lévi-Strauss and Antoine de Saint-Exupéry Letters to the Editor ...................................6-7 were among the large and distinguished group of French artists, writers and Art Notes...................................................... 8 intellectuals who fled to America to spend the war. Sending children across the pond ................. 9 My cousin Otto .....................................10-11 In six weeks from 10 May 1940 bills. At one point, Wilder was staying Great Britain rules the waves ...................... 12 German forces conquered Belgium, the in the same cheap boarding-house as Revisiting emotional visits........................... 13 Netherlands and France. -

New Mexico Lobo, Volume 056, No 67, 3/30/1954." 56, 67 (1954)

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository 1954 The aiD ly Lobo 1951 - 1960 3-30-1954 New Mexico Lobo, Volume 056, No 67, 3/30/ 1954 University of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/daily_lobo_1954 Recommended Citation University of New Mexico. "New Mexico Lobo, Volume 056, No 67, 3/30/1954." 56, 67 (1954). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ daily_lobo_1954/29 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The aiD ly Lobo 1951 - 1960 at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in 1954 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. '''-::::--''i~' !!!!I!!!!!!"!!,,2!!!!J~,",,.!!!!~!I!!"_!!!!I«!!II_!!!"_!!!,,_!!!!!S!!!!!2!!!!!A!!!!,,,"!!',,,_!!!!. £Q!!!!." ,!!!!,_"!!'_!!!! ..!!!!!!!I!S"!!!!,_!!!!.,,,!!!!:e::~._~_!!!!l.=,,,,,.,,,, ="_"'~""',.""n""••.",,_.,,, __ ::===. ='~"'k""",,,=.=,,,,=_.,_.~_~_,,,.·,,,,_ .. _,,, , I ~, the sake of fighting. Deborllh KeJ;r lin her movie set aud "sta$d heck. abal)dons her hitherto regllI and News . .• ling" hili! former lllve. )fiss Winters .J>tM'N GEMS proper. characterizations til appear Continued from page 1 , said" Th1,!rsday ,Elhe" was Borry , •• The ooginning Ilf as the"lu$h" sweater-clad and ,un· she had mill~ed him. the end. ' haPpy Army wife whose chance WOJ:k9rll, general economic condition ••• One Star EW: Amllur wjth her husband's first Ber of country ••. at the same news EXIcoLoB conference expressed himself as be. The BaltimoJ:e Orioles, with a gellnt turns into something unex ing opposed t(l anyone "sitting' in WIlJl ,,10-lost 5 record so :(ar ill thl) "The Voieeof a Great Southwestern University" pected but underf!tandable. -

Mozart's String Quartet in D Minor, K

THE BIOGRAPHY OF A STRING QUARTET: Mozart’s String Quartet in D minor, K. 421 (417b) by Alexa Vivien Wilks A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Faculty of Music University of Toronto © Copyright by Alexa Vivien Wilks 2015 The Biography of a String Quartet: Mozart’s String Quartet in D minor, K. 421 (417b) Alexa Vivien Wilks Doctor of Musical Arts Faculty of Music University of Toronto 2015 Abstract Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s String Quartet K. 421 in D minor remains one of his most celebrated quartets. K. 421 is the second work in a set of six quartets dedicated to Mozart’s colleague and mentor, Joseph Haydn, and is the only ‘Haydn’ Quartet in a minor key. An overview of the historical background of K. 421, the significance of D minor in Mozart’s compositions, as well as the compositional relationship between Mozart and Haydn situates this work amongst Mozart’s other string quartet compositions and provides context for the analysis of different editions. An outline of the historical practices and roles of editors, as well as a detailed analysis and comparison of different editions against the autograph manuscript and the first edition published by Artaria in 1785 examines the numerous discrepancies between each of the different publications of K. 421. Using the information acquired from the comparative study of selected historical editions, some possibilities for future editions of K. 421 are discussed. When undertaking the study of a new quartet, performers can learn a great deal from listening to recordings.