"It's Like We Were Being Watched ... Like There Were Only 3 Walls, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information Packet for Prospective Students

Information Packet for Prospective Students This packet includes: ! Information about our major ! FAQs ! Press packet with news items on our students, faculty and alumni Be sure to visit our website for more information about our department: http://film.ucsc.edu/ For information about our facilities and to watch student films, visit SlugFilm: http://slugfilm.ucsc.edu/ If you have any questions, you can send an email to [email protected] Scroll Down for packet information More%information%can%be%found%on%the%UCSC%Admissions%website:%% UC Santa Cruz Undergraduate Admissions Film and Digital Media Introduction The Film and Digital Media major at UC Santa Cruz offers an integrated curriculum where students study the cultural impact of movies, television, video, and the Internet and also have the opportunity to pursue creating work in video and interactive digital media, if so desired. Graduates of the UC Santa Cruz Film and Digital Media program have enjoyed considerable success in the professional world and have gained admission to top graduate schools in the field. Degrees Offered ▪ B.A. ▪ M.A. ▪ Minor ▪ Ph.D. Study and Research Opportunities Department-sponsored independent field study opportunities (with faculty and department approval) Information for First-Year Students (Freshmen) High school students who plan to major in Film and Digital Media need no special preparation other than the courses required for UC admission. Freshmen interested in pursuing the major will find pertinent information on the advising web site, which includes a first-year academic plan. advising.ucsc.edu/summaries/summary-docs/FILM_FR.pdf Information for Transfers Transfer students should speak with an academic adviser at the department office prior to enrolling in classes to determine their status and to begin the declaration of major process as soon as possible. -

The Girl in the Woods: on Fairy Stories and the Virgin Horror

Journal of Tolkien Research Volume 10 Issue 1 J.R.R. Tolkien and the works of Joss Article 3 Whedon 2020 The Girl in the Woods: On Fairy Stories and the Virgin Horror Brendan Anderson University of Vermont, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch Recommended Citation Anderson, Brendan (2020) "The Girl in the Woods: On Fairy Stories and the Virgin Horror," Journal of Tolkien Research: Vol. 10 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch/vol10/iss1/3 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Christopher Center Library at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Tolkien Research by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Anderson: The Girl in the Woods THE GIRL IN THE WOODS: ON FAIRY STORIES AND THE VIRGIN HORROR INTRODUCTION The story is an old one: the maiden, venturing out her door, ignores her guardian’s prohibitions and leaves the chosen path. Fancy draws her on. She picks the flow- ers. She revels in her freedom, in the joy of being young. Then peril appears—a wolf, a monster, something with teeth for gobbling little girls—and she learns, too late, there is more to life than flowers. The girl is destroyed, but then—if she is lucky—she returns a woman. According to Maria Tatar (while quoting Catherine Orenstein): “the girl in the woods embodies ‘complex and fundamental human concerns’” (146), a state- ment at least partly supported by its appearance in the works of both Joss Whedon and J.R.R. -

SUE BLAINEY, ACE Editor

SUE BLAINEY, ACE Editor PROJECTS Partial List DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS POWER BOOK III: RAISING KANAN Various Directors STARZ / LIONSGATE TV Season 1 Tim Christenson, Bart Wenrich Shana Stein, Courtney Kemp, Sascha Penn THE WALKING DEAD: WORLD BEYOND Michael Cudlitz AMC Season 1, Episode 7 Jonathan Starch, Matt Negrete THE GOOD LORD BIRD Albert Hughes SHOWTIME / BLUMHOUSE Limited Series O’Shea Read, Olga Hamlet STRANGE ANGEL David Lowery SCOTT FREE / CBS Pilot & Season 1 - 2 David Zucker, Mark Heyman WHAT IF Various Directors WARNER BROS. / NETFLIX Series Mike Kelley 13 REASONS WHY Various Directors PARAMOUNT TV / NETFLIX Season 2 Kim Cybulski, Brian Yorkey ANIMAL KINGDOM Various Directors WARNER BROS. / TNT Season 1 Terri Murphy, Lou Wells 11/22/63 Kevin MacDonald BAD ROBOT / HULU Series Jill Risk, Bridget Carpenter THE MAGICIANS Mike Cahill SYFY / Desiree Cadena, John McNamara Pilot Michael London MOZART IN THE JUNGLE Paul Weitz AMAZON Season 1 Caroline Baron, Roman Coppola Jason Schwartzman, Paul Weitz UN-REAL Roger Kumble LIFETIME Pilot Sarah Shapiro, Marti Noxon IN PLAIN SIGHT Various Directors NBC Season 3 Dan Lerner, John McNamara Consulting Producer Karen Moore HAPPY TOWN Darnell Martin ABC Season 1 Mick Garris Paul Rabwin, Josh Appelbaum John Polson André Nemec EASY VIRTUE Stephan Elliott EALING STUDIOS Toronto Film Festival Barnaby Thompson, Alexandra Ferguson THE HILLS HAVE EYES 2 Martin Weisz FOX / ATOMIC Co-Editor Wes Craven, Marianne Maddalena SIX DEGREES David Semel BAD ROBOT / ABC Series Wendey Stanzler J.J. Abrams, Jane Raab, Bryan Burke LOST Jack Bender ABC Season 2 Finale J.J. Abrams, Ra’uf Glasgow, Bryan Burke Nomination, Best Editing – ACE Eddie Awards Nomination, Best Editing – Emmy Awards HOUSE Greg Yaitanes FOX Series Keith Gordon Katie Jacobs, David Shore SIX FEET UNDER Kathy Bates HBO Series Migel Arteta Alan Ball, Alan Poul Lisa Cholodenko THE ADVENTURES OF PRISCILLA Stephan Elliott POLYGRAM QUEEN OF THE DESERT Al Clark, Michael Hamlyn Cannes Film Festival INNOVATIVE-PRODUCTION.COM | 310.656.5151 . -

MGM-Halloween-3

S CHOLASTIC ELT READERS A FREE RESOURCE FOR TEACHERS! HALLOWEEN–EXTRA Level 1 This level is suitable for students who have been learning English for at least a year and up to two years. It corresponds with the Common European Framework level A1. Suitable for users of CLICK magazine. SYNOPSIS Sunnydale is a small town in California. The action centres It’s Halloween. Buffy and friends hire costumes and take around the High School. Buffy and her friends are students and children out trick-or-treating (see Fact File 2). Everyone’s having Rupert Giles, Buffy’s Watcher or guide, is the librarian. Buffy, the fun. But there’s someone new in Sunnydale who wants to spoil Chosen One, has been sent to Sunnydale because the entrance their fun. His name is Ethan, he’s opened a Costume Shop and to Hell – the Hellmouth – is in the basement of the school. he has evil plans. Ethan casts a spell (he’s actually a sorcerer). The show combines comedy, tragedy, martial arts, romance Whatever costume people hired from him, that’s what they turn and horror. The stories also deal with teenage issues of love, into. Vampire-slaying Buffy loses her powers and becomes a self-esteem and planning a future, and use the fights with cowardly noblewoman from 1775. Willow becomes a ghost and supernatural forces as metaphors for emotional anxieties. Xander turns into a real-life soldier. The vampires are delighted. Halloween is Episode 6 from Series 2, so it’s quite near the Buffy and friends find themselves imprisoned in an old beginning. -

GARRET DONNELLY EDITOR TELEVISION PAINKILLER (Limited Series) Netflix Prod: Eric Newman, Micah Fitzerman-Blue Dir: Peter Berg Noah Harpster

GARRET DONNELLY EDITOR TELEVISION PAINKILLER (Limited Series) Netflix Prod: Eric Newman, Micah Fitzerman-Blue Dir: Peter Berg Noah Harpster NARCOS: MEXICO (Season 1-3) Netflix Prod: Eric Newman, Tim King Dir: Josef Kubota Wladyka Amat Escalante Andres Baiz NOS4A2 (Season 2) AMC Prod: Jami O’Brien Dir: Craig William MacNeill KNIGHTFALL (Season 2) The History Channel Prod: Aaron Helbing, Josh Appelbaum Dir: Rick Jacobson Andre Nemic, Jeff Pickner David Wellington Scott Rosenberg HEATHERS (Season 1) Paramount Network Prod: Jason Micallef, Tom Rosenberg Dir: Adam Silver Gary Lucchesi, Annie Mebane Jessica Lowrey Keith Raskin THE NIGHT SHIFT (Season 4) Sony TV/NBC Prod: Jeff Judah, Gabe Sachs, Tom Garrigus Dir: Various 24: LEGACY (Season 1) 20th Century Fox/FOX Prod: Evan Katz, Manny Coto, Jon Cassar Dir: Nelson McCormick Howard Gordon, Stephen Hopkins Jon Cassar TYRANT (Seasons 2-3) 20th Century Fox/FX Prod: Chris Keyser, Howard Gordon Dir: Various Glenn Gordon Caron, David Fury SECOND CHANCE (Season 1) 20th Century Fox/FOX Prod: Rand Ravich, Donald Todd Dir: Various Howard Gordon, Brad Turner HOMELAND (Episodes 401, 412) Fox 21/Showtime Prod: Alex Gansa, Howard Gordon Dir: Lesli Linka Glatter RAY DONOVAN (Episode 204) Showtime Prod: Ann Biderman Dir: Tucker Gates ASSISTANT EDITOR (TELEVISION) PROOF (Season 1) TNT Productions/TNT Prod: Rob Bragin, Jessica Grasi, Rose Lam Dir: Allison Anders HOMELAND (Seasons 1-4) Fox 21/Showtime Prod: Alex Gansa, Howard Gordon Dir: Various RAY DONOVAN (Pilot, Seasons 1-2) Showtime Prod: Ann Biderman Dir: Allen Coulter (P) Various THE KILLING (Season 2) Fox 21/AMC Prod: Veena Sud Dir: Various CHAOS (Season 1) 20th Century Fox/CBS Prod: Tom Spezialy Dir: Various MEDIUM (Seasons 3-7) CBS Studios/NBC Prod: Glenn Gordon Caron Dir: Various FEATURES BROKEN BOY SOLDIER (Short) Burnside Entertainment Prod: Seth William Meier Dir: Travis Donnelly 405 S Beverly Drive, Beverly Hills, California 90212 - T 310.888.4200 - F 310.888.4242 www.apa-agency.com . -

A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works Krista Silva University of Puget Sound, [email protected]

Student Research and Creative Works Book Collecting Contest Essays University of Puget Sound Year 2015 The Wonderful World of Whedon: A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works Krista Silva University of Puget Sound, [email protected] This paper is posted at Sound Ideas. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/book collecting essays/6 Krista Silva The Wonderful World of Whedon: A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works I am an inhabitant of the Whedonverse. When I say this, I don’t just mean that I am a fan of Joss Whedon. I am sincere. I live and breathe his works, the ever-expanding universe— sometimes funny, sometimes scary, and often heartbreaking—that he has created. A multi- talented writer, director and creator, Joss is responsible for television series such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer , Firefly , Angel , and Dollhouse . In 2012 he collaborated with Drew Goddard, writer for Buffy and Angel , to bring us the satirical horror film The Cabin in the Woods . Most recently he has been integrated into the Marvel cinematic universe as the director of The Avengers franchise, as well as earning a creative credit for Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. My love for Joss Whedon began in 1998. I was only eleven years old, and through an incredible moment of happenstance, and a bit of boredom, I turned the television channel to the WB and encountered my first episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer . I was instantly smitten with Buffy Summers. She defied the rules and regulations of my conservative southern upbringing. -

Narrowing the Gap Between Imaginary and Real Artifacts: a Process for Making and Filming Diegetic Prototypes

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Narrowing the Gap Between Imaginary and Real Artifacts: A Process for Making and Filming Diegetic Prototypes Al Hussein Wanas Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Art and Design Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/3142 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Al Hussein Wanas 2013 All Rights Reserved 2 Approval certificate for Al Hussein Wanas for the thesis project entitled Narrowing The Gap Between Imaginary And Real Artifacts: A Process For Making And Filming Diegetic Prototypes. Submitted to the faculty of the Master of Fine Arts in Design Studies of Virginia Commonwealth University in Qatar in partial fulfillment for the degree, Master of Fine Arts in Design Studies. Al Hussein Wanas, BFA In Graphic Design, Virginia Commonwealth University in Qatar, Doha Qatar, May 2011. Virginia Commonwealth University in Qatar, Doha Qatar, May 2013 Diane Derr ______________________ Primary Advisor, Assistant Professor Master of Fine Arts in Design Studies Patty Paine ______________________ Secondary Advisor, Reader, Assistant Professor Liberal Arts and Science Levi Hammett ______________________ Secondary -

Joss Whedon Versus the Corporation : Big Business Critiqued in the Films and Television Programs

JOSS WHEDON VERSUS THE CORPORATION : BIG BUSINESS CRITIQUED IN THE FILMS AND TELEVISION PROGRAMS Author: Erin Giannini Number of Pages: 223 pages Published Date: 30 Jan 2018 Publisher: McFarland & Co Inc Publication Country: Jefferson, NC, United States Language: English ISBN: 9781476667768 DOWNLOAD: JOSS WHEDON VERSUS THE CORPORATION : BIG BUSINESS CRITIQUED IN THE FILMS AND TELEVISION PROGRAMS Joss Whedon Versus the Corporation : Big Business Critiqued in the Films and Television Programs PDF Book about the author: Dr. Martha Chesler, 54, lost 11 pounds. " So begins Deirdre Chetham's elegiac book about the towns along the banks of the Three Gorges area of the Yangtze River, written on the very eve of their destruction. Opler's classic Culture, Psychiatry, and Human Values has here been revised and expanded to nearly twice the size of the original work. Digital Photography For DummiesA new edition gets you in the picture for learning digital photography Whether you have a point-and-shoot or digital SLR camera, this new edition of the full-color bestseller is packed with tips, advice, and insight that you won't find in your camera manual. In The Art of Woo, they present their systematic, four- step process for winning over even the toughest bosses and most skeptical colleagues. An Introduction to Language and Linguistics: Breaking the Language SpellChristopher Hall's book is the best new introduction to linguistics that I have seen in decades. Learn How to Get a Job and Succeed as a -CARGO SHIP CAPTAIN- Find out the secrets of scoring YOUr dream job. ' Paul Ernest, Emeritus Professor of Mathematics Education, University of Exeter Teaching mathematics can be challenging, and returning to a mathematics classroom yourself may not inspire you with confidence. -

The Relationship Between Plot and Genre in Short Fiction ASHLEY R LISTER a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Bolton Institutional Repository (UBIR) Five Plots: The Relationship Between Plot and Genre in Short Fiction ASHLEY R LISTER A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Bolton for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. February 2018 Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................ iii Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: Literature Review ...................................................................................................... 9 An Interpretation of Genre .......................................................................................................... 9 The Components of Plot ........................................................................................................... 21 Chapter 2: Methodology ............................................................................................................. 34 A Different Approach ................................................................................................................. 34 Chapter 3: The Horror Genre ................................................................................................... -

PATRICK B. SHARP Curriculum Vitae (As of February 2013)

PATRICK B. SHARP Curriculum Vitae (as of February 2013) Chair, Department of Liberal Studies California State University, Los Angeles 5151 State University Drive Los Angeles, CA 90032 Office: (323) 343-4100 http://www.calstatela.edu/faculty/psharp [email protected] EDUCATION Degrees Ph. D. in English University of California, Santa Barbara 1999 The White Man's Bomb: Race and Nuclear Apocalypse Narrative in American Culture. M.A. in English University of California, Santa Barbara 1994 B.A. in English (High Honors) University of California, Santa Barbara 1989 Completed the Education Abroad Program at the University of Oslo, Norway during the summer of 1987 and at the University of Bergen, Norway during the 1987-88 academic year Non-Degree American Association of Colleges and Universities Institute on High-Impact Practices and Student Success, University of Vermont 2011 American Association of Colleges and Universities Institute on Making General Education Relevant, San Francisco 2011 California State University Workshop on ePortfolios, San Jose 2009 American Association of Colleges and Universities Institute on General Education, University of Minnesota 2009 CURRENT POSITION AND RESPONSIBILITIES California State University, Los Angeles Chair, Department of Liberal Studies September 2010-Present Cal State L. A. is an urban comprehensive university and one of twenty-three campuses in the CSU system. The Department of Liberal Studies has over 400 undergraduate majors pursuing options in Interdisciplinary Studies of Culture and Society and Elementary Teacher Preparation. Liberal Studies also has a popular minor in Women's and Gender Studies and several popular general education courses. The chair manages the budget and allocates all departmental resources. -

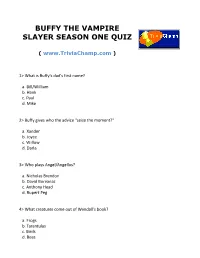

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Season One Quiz

BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER SEASON ONE QUIZ ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> What is Buffy's dad's first name? a. Bill/William b. Hank c. Paul d. Mike 2> Buffy gives who the advice "seize the moment?" a. Xander b. Joyce c. Willow d. Darla 3> Who plays Angel/Angellus? a. Nicholas Brendon b. David Boreanaz c. Anthony Head d. Rupert Peg 4> What creatures come out of Wendall's book? a. Frogs b. Tarantulas c. Birds d. Bees 5> Under Moloch's direction, what does Dave try to do to Buffy? a. Electrocute her b. Kiss her c. Stab her d. Hang her 6> Who steps in to take Marcie away? a. Angel b. Vampires c. Sunnydale Police Department d. The FBI 7> According to Giles, the earth began as what type of place? a. A home for demons b. A land for mortals c. A wasteland d. A paradise 8> What was Buffy's biology teacher's name? a. Mr. Smith b. Dr. Gregory c. Dr. Paulson d. Mr. Herring 9> What is the name of Buffy's first watcher? a. Signer b. Wilford c. Merrick d. Giles 10> Who gives Buffy a cross necklace? a. Spike b. Giles c. Cordelia d. Angel 11> What was principal Flutie's first name? a. Bob b. Ralph c. Steve d. Roy 12> What of Buffy's does Cordelia say is "over?" a. Her hairstyle b. Her shoes c. Her earrings d. Her nail polish 13> What was the name of the invisible girl? a. Marcia Craig b. Meg Stevens c. -

The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 2010 "Just a Girl": The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007 Tamy Burnett University of Nebraska at Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons Burnett, Tamy, ""Just a Girl": The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007" (2010). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 27. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. “JUST A GIRL”: THE COMMUNITY-CENTERED CULT TELEVISION HEROINE, 1995-2007 by Tamy Burnett A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: English (Specialization: Women‟s and Gender Studies) Under the Supervision of Professor Kwakiutl L. Dreher Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2010 “JUST A GIRL”: THE COMMUNITY-CENTERED CULT TELEVISION HEROINE, 1995-2007 Tamy Burnett, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2010 Adviser: Kwakiutl L. Dreher Found in the most recent group of cult heroines on television, community- centered cult heroines share two key characteristics. The first is their youth and the related coming-of-age narratives that result.