Mr Francis Harry Hinsley Roll of Honour Bletchleypark.Org

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

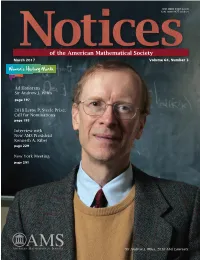

Sir Andrew J. Wiles

ISSN 0002-9920 (print) ISSN 1088-9477 (online) of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 Volume 64, Number 3 Women's History Month Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Wiles page 197 2018 Leroy P. Steele Prize: Call for Nominations page 195 Interview with New AMS President Kenneth A. Ribet page 229 New York Meeting page 291 Sir Andrew J. Wiles, 2016 Abel Laureate. “The definition of a good mathematical problem is the mathematics it generates rather Notices than the problem itself.” of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 FEATURES 197 239229 26239 Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Interview with New The Graduate Student Wiles AMS President Kenneth Section Interview with Abel Laureate Sir A. Ribet Interview with Ryan Haskett Andrew J. Wiles by Martin Raussen and by Alexander Diaz-Lopez Allyn Jackson Christian Skau WHAT IS...an Elliptic Curve? Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof by by Harris B. Daniels and Álvaro Henri Darmon Lozano-Robledo The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles by Christopher Skinner In this issue we honor Sir Andrew J. Wiles, prover of Fermat's Last Theorem, recipient of the 2016 Abel Prize, and star of the NOVA video The Proof. We've got the official interview, reprinted from the newsletter of our friends in the European Mathematical Society; "Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof" by Henri Darmon; and a collection of articles on "The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles" assembled by guest editor Christopher Skinner. We welcome the new AMS president, Ken Ribet (another star of The Proof). Marcelo Viana, Director of IMPA in Rio, describes "Math in Brazil" on the eve of the upcoming IMO and ICM. -

The Destruction of Convoy PQ.17

The Destruction of Convoy PQ.17 DAVID IRVING Simon and Schuster: New York This PDF version: © Focal Point Publications 2002 i Report errors ii This PDF version: © Focal Point Publications 2002 Report errors Jacket design of the original Cas This PDF version: © Focal Point Publications 2002 iii Report errors ssell & Co. edition, London, This is the original text of The Destruction of Convoy PQ. as first published in . In order to comply with an order made in the Queen’s Bench division of the High Court in , after the libel action brought by Captain John Broome, a number of passages have been blanked out. In 1981 a revised and updated edition was published by William Kimber Ltd. incorporating the minor changes required by Broome’s solicitors. First published in Great Britain by Cassell & Co. Limited Copyright © David Irving , Electronic edition © Focal Point Publications All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. This electronic Internet edition is made avaiolable for leisure reading and research purposes only, and any commercial exploitation of the work without the written consent of the copyright owners will be prosecuted. iv This PDF version: © Focal Point Publications 2002 Report errors INTRODUCTION All books have something which their authors most wish to bring to their readers’ attention. Some authors are successful in this, -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

The Essential Turing: Seminal Writings in Computing, Logic, Philosophy, Artificial Intelligence, and Artificial Life: Plus the Secrets of Enigma

The Essential Turing: Seminal Writings in Computing, Logic, Philosophy, Artificial Intelligence, and Artificial Life: Plus The Secrets of Enigma B. Jack Copeland, Editor OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS The Essential Turing Alan M. Turing The Essential Turing Seminal Writings in Computing, Logic, Philosophy, Artificial Intelligence, and Artificial Life plus The Secrets of Enigma Edited by B. Jack Copeland CLARENDON PRESS OXFORD Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Taipei Toronto Shanghai With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan South Korea Poland Portugal Singapore Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © In this volume the Estate of Alan Turing 2004 Supplementary Material © the several contributors 2004 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2004 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. -

Joan Clarke at Station X

Joan Clarke at Station X Before Joan Clarke worked at Bletchley Park’s Hut 8, she already knew Alan Turing. He was a friend of Joan’s brother. A very intelligent young woman, Joan studied mathematics at Cambridge University’s Newnham College. Gordon Welchman, who was working for the Government Code & Cypher School in the late 1930s, recruited Joan to work at Bletchley Park. He’d been her Geometry supervisor at Cambridge. At the time, women did not typically fill important jobs at Bletchley Park (or anywhere else throughout Britain). So ... at the beginning of her work at Station X ... Joan filled a clerical slot. It took very little time, however, for Joan to get her “own table” inside Hut 8. This promotion effectively placed her on Turing’s code-breaking team. Not only did Joan do great work at Bletchley, by 1944 she was deputy-head of the Hut-8 team. During the early part of her work at Station X, Joan had been promoted to a “Linguist,” even though she wasn’t fluent in other languages. (It was just a way for her to receive better pay for her work.) She once answered a questionnaire with these words: Grade: Linguist, Languages: None. When she first became a Hut-8 code breaker, Joan worked with Alan Turing, Tony Kendrick and Peter Twinn. Their actual work focused on breaking Germany’s Naval Enigma code (which the Station X workers had codenamed “Dolphin”). Joan and Alan Turing became very close friends and, in 1941, the head of Hut 8 asked his friend to become his wife. -

![The Influence of ULTRA in the Second World War [ Changed 26Th November 1996 ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0237/the-influence-of-ultra-in-the-second-world-war-changed-26th-november-1996-2180237.webp)

The Influence of ULTRA in the Second World War [ Changed 26Th November 1996 ]

The Influence of ULTRA in the Second World War [ Changed 26th November 1996 ] Last year Sir Harry Hinsley kindly agreed to speak about Bletchley Park, where he worked during the Second World War. We are pleased to present a transcript of his talk. Sir Harry Hinsley is a distinguished historian who during the Second World War worked at Bletchley Park, where much of the allied forces code-breaking effort took place. We are pleased to include here a transcript of his talk, and would like to thank Susan Cheesman for typing the first draft and Keith Lockstone for adding Sir Harry's comments and amendments. Security Group Seminar Speaker: Sir Harry Hinsley Date: Tuesday 19th October 1993 Place: Babbage Lecture Theatre, Computer Laboratory Title: The Influence of ULTRA in the Second World War Ross Anderson: It is a great pleasure to introduce today's speaker, Sir Harry Hinsley, who actually worked at Bletchley from 1939 to 1946 and then came back to Cambridge and became Professor of the History of International Relations and Master of St John's College. He is also the official historian of British Intelligence in World War II, and he is going to talk to us today about Ultra. Sir Harry: As you have heard I've been asked to talk about Ultra and I shall say something about both sides of it, namely about the cryptanalysis and then on the other hand about the use of the product - of course Ultra was the name given to the product. And I ought to begin by warning you, therefore, that I am not myself a mathematical or technical expert. -

Download (15Mb)

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/67105 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. Never To Be Disclosed: Government Secrecy in Britain 1945 - 1975 by Christopher R. Moran BA, MA A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Warwick, Department of History September 2008 CONTENTS Acknowledgements iv Docwadoo v Abbrenaaons vii Introduction INever to Be Disclosed 1 Chapter 11The Official Secrets Act: Genesis and Evolution 21 1.1 1850- 1889 22 1.21890-1920 35 Conclusions 43 Chapter 21A Silent Service: The Culture of Civil Service Secrecy 45 2.1Anonymity and Neutrality 50 2.2Security Routines 55 2.3"The Official Secrets Act Affects You!" 71 2.4 Raising the Curtain? 75 Conclusions 91 Chapter 31 Harry 'Chapman' Pincher: Sleuthing the Secret State 93 3.11945-1964 97 3.2The D-Notice Affair 107 3.31967-1975 124 Conclusions 132 Chapter 41The Riddle of the Frogman: The Crabb Affair, Secrecy and Cold War Culture 135 4.1 Disappearance 138 4.2 Conspiracy and Popular Culture 144 4.3Operation Claret 149 4.4 Backwash 156 Conclusions 159 Chapter 51Light in Dark Comers: Intelligence Memoirs and Official History -

Jack Copeland on Enigma

Enigma Jack Copeland 1. Turing Joins the Government Code and Cypher School 217 2. The Enigma Machine 220 3. The Polish Contribution, 1932–1940 231 4. The Polish Bomba 235 5. The Bombe and the Spider 246 6. Naval Enigma 257 7. Turing Leaves Enigma 262 1. Turing Joins the Government Code and Cypher School Turing’s personal battle with the Enigma machine began some months before the outbreak of the Second World War.1 At this time there was no more than a handful of people in Britain tackling the problem of Enigma. Turing worked largely in isolation, paying occasional visits to the London oYce of the Government Code and Cypher School (GC & CS) for discussions with Dillwyn Knox.2 In 1937, during the Spanish Civil War, Knox had broken the type of Enigma machine used by the Italian Navy.3 However, the more complicated form of Enigma used by the German military, containing the Steckerbrett or plug-board, was not so easily defeated. On 4 September 1939, the day following Chamberlain’s announcement of war with Germany, Turing took up residence at the new headquarters of the Govern- ment Code and Cypher School, Bletchley Park.4 GC & CS was a tiny organization 1 Letters from Peter Twinn to Copeland (28 Jan. 2001, 21 Feb. 2001). Twinn himself joined the attack on Enigma in February 1939. Turing was placed on Denniston’s ‘emergency list’ (see below) in March 1939, according to ‘StaV and Establishment of G.C.C.S.’ (undated), held in the Public Record OYce: National Archives (PRO), Kew, Richmond, Surrey (document reference HW 3/82). -

JOHN PLUMB 15 Plumb 1226 15/11/2004 10:41 Page 269

15 Plumb 1226 15/11/2004 10:41 Page 268 JOHN PLUMB 15 Plumb 1226 15/11/2004 10:41 Page 269 John Harold Plumb 1911–2001 SIR JOHN PLUMB, who died on 21 October 2001, having celebrated his ninetieth birthday two months before, had been in ill health for some time —but in rude health for a great deal longer. To his friends, and also to his enemies, he was always known as ‘Jack’, and he invariably published over the uncharacteristically tight-lipped by-line of J. H. Plumb. On both sides of the Atlantic, the many obituaries and appreciations rightly drew atten- tion to his memorable character and ample wealth, to his irrepressible vitality and unabashed delight in the good things of life, to the light and the dark of his complex and conflicted nature, and to the ups and downs of his professional career. They also stressed his equivocal relationship with Cambridge University (where he failed to gain an undergraduate scholarship, but was Professor of Modern British History from 1966 to 1974), his nearly seventy-year-long connection with Christ’s College (where he was a Fellow from 1946 to 1978, Master from 1978 to 1982, and then again a Fellow until his death), and his latter-day conversion (if such it was) from impassioned radical to militant Thatcherite. And they noted the human insight and sparkling style that were the hallmarks of his best work, his lifelong conviction that history must reach a broad audience and inform our understanding of present-day affairs, and his unrivalled skills in nurturing (and often terrifying) youthful promise and scholarly talent.1 1 Throughout these notes, I have abbreviated Sir John Plumb to JHP, and C. -

Commerce Raiding Historical Case Studies, 1755–2009 NEWPORT PAPERS

NAVAL WAR COLLEGE NEWPORT PAPERS 40 NAVAL WAR COLLEGE WAR NAVAL Commerce Raiding Historical Case Studies, 1755–2009 NEWPORT PAPERS NEWPORT Bruce A. Elleman and S. C. M. Paine, Editors Form Approved Report Documentation Page OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for the collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to a penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. 1. REPORT DATE 3. DATES COVERED 2. REPORT TYPE OCT 2013 00-00-2013 to 00-00-2013 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER Commerce Raiding: Historical Case Studies, 1755?2009 5b. GRANT NUMBER 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER 5e. TASK NUMBER 5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION Naval War College,Center for Naval Warfare Studies,686 Cushing REPORT NUMBER Rd,Newport,RI,02841-1207 9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. SPONSOR/MONITOR’S ACRONYM(S) 11. SPONSOR/MONITOR’S REPORT NUMBER(S) 12. -

The Essential Turing : Seminal Writings in Computing, Logic, Philosophy, Artificial Intelligence, and Artificial Life, Plus

The Essential Turing: Seminal Writings in Computing, Logic, Philosophy, Artificial Intelligence, and Artificial Life: Plus The Secrets of Enigma B. Jack Copeland, Editor OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS The Essential Turing Alan M. Turing The Essential Turing Seminal Writings in Computing, Logic, Philosophy, Artificial Intelligence, and Artificial Life plus The Secrets of Enigma Edited by B. Jack Copeland CLARENDON PRESS OXFORD Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Taipei Toronto Shanghai With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan South Korea Poland Portugal Singapore Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © In this volume the Estate of Alan Turing 2004 Supplementary Material © the several contributors 2004 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2004 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. -

Breaking Germany's Enigma Code

Breaking Germany’s Enigma Code By Andrew Lycett (Obtained from the Internet) Germany’s armed forces believed their Enigma-encrypted communications were impenetrable to the Allies. But thousands of codebreakers - based in wooden huts at Britain’s Bletchley Park - had other ideas. This author investigates how successful they were, and the difference they made to the war effort. The Enigma “typewriter” In 2001, the release of the feature film Enigma sparked great interest in the tweedy world of the boffins who broke Nazi Germany’s secret wartime communications codes. But not all who watched Dougray Scott in the film’s lead role realised that the title referred to a machine like a typewriter, which encrypted secret messages. Fewer people still knew that this piece of spook hardware was invented by a German (based on an idea by a Dutchman), that information about it was leaked to the French, and that it was first reconstructed by a Pole, before it was offered to Britain’s codebreakers as a way of deciphering German signals traffic during World War II. As a result of the information gained through this device, it has been claimed, hostilities between Germany and the Allied forces were curtailed by two years. The importance of signals intelligence became evident during World War I, as staff in the British Admiralty’s Room 40, under Captain Reginald “Blinker” Hall, worked at intercepting German communications. Among these, famously, was the Zimmermann telegram - a message from the German foreign minister to his ambassador in Mexico City informing him of plans to invade the United States.