Obituaries 1990S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

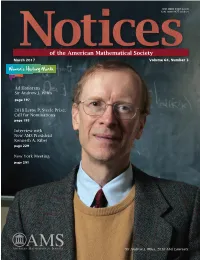

Sir Andrew J. Wiles

ISSN 0002-9920 (print) ISSN 1088-9477 (online) of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 Volume 64, Number 3 Women's History Month Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Wiles page 197 2018 Leroy P. Steele Prize: Call for Nominations page 195 Interview with New AMS President Kenneth A. Ribet page 229 New York Meeting page 291 Sir Andrew J. Wiles, 2016 Abel Laureate. “The definition of a good mathematical problem is the mathematics it generates rather Notices than the problem itself.” of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 FEATURES 197 239229 26239 Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Interview with New The Graduate Student Wiles AMS President Kenneth Section Interview with Abel Laureate Sir A. Ribet Interview with Ryan Haskett Andrew J. Wiles by Martin Raussen and by Alexander Diaz-Lopez Allyn Jackson Christian Skau WHAT IS...an Elliptic Curve? Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof by by Harris B. Daniels and Álvaro Henri Darmon Lozano-Robledo The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles by Christopher Skinner In this issue we honor Sir Andrew J. Wiles, prover of Fermat's Last Theorem, recipient of the 2016 Abel Prize, and star of the NOVA video The Proof. We've got the official interview, reprinted from the newsletter of our friends in the European Mathematical Society; "Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof" by Henri Darmon; and a collection of articles on "The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles" assembled by guest editor Christopher Skinner. We welcome the new AMS president, Ken Ribet (another star of The Proof). Marcelo Viana, Director of IMPA in Rio, describes "Math in Brazil" on the eve of the upcoming IMO and ICM. -

Smythe-Wood Series A

Smythe-Wood Newspaper Index – “A” series – mainly Co Tyrone Irish Genealogical Research Society Dr P Smythe-Wood’s Irish Newspaper Index Selected families, mainly from Co Tyrone ‘Series A’ The late Dr Patrick Smythe-Wood presented a large collection of card indexes to the IGRS Library, reflecting his various interests, - the Irish in Canada, Ulster families, various professions etc. These include abstracts from various Irish Newspapers, including the Belfast Newsletter, which are printed below. Abstracts are included for all papers up to 1864, but excluding any entries in the Belfast Newsletter prior to 1801, as they are fully available online. Dr Smythe-Wood often found entries in several newspapers for the one event, & these will be shown as one entry below. Entries dealing with RIC Officers, Customs & Excise Officers, Coastguards, Prison Officers, & Irish families in Canada will be dealt with in separate files, although a small cache of Canadian entries is included here, being families closely associated with Co Tyrone. In most cases, Dr Smythe-Wood has recorded the exact entry, but in some, marked thus *, the entries were adjusted into a database, so should be treated with more caution. There are further large card indexes of Miscellaneous notes on families which are not at present being digitised, but which often deal with the same families treated below. ANC: Anglo-Celt LSL Londonderry Sentinel ARG Armagh Guardian LST Londonderry Standard/Derry Standard BAI Ballina Impartial LUR Lurgan Times BAU Banner of Ulster MAC Mayo Constitution -

Ebook Download Muhammad Ali Ebook, Epub

MUHAMMAD ALI PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Thomas Hauser | 544 pages | 15 Jun 1992 | SIMON & SCHUSTER | 9780671779719 | English | New York, United States Muhammad Ali PDF Book Retrieved May 20, Retrieved November 5, Federal Communications Commission. Vacant Title next held by George Foreman. Irish Independent. Get used to me. Sonny Liston - Boxen". Ellis Ali vs. Ali conceded "They didn't tell me about that in America", and complained that Carter had sent him "around the world to take the whupping over American policies. The Guardian. Armed Forces, but he refused three times to step forward when his name was called. Armed Forces qualifying test because his writing and spelling skills were sub-standard, [] due to his dyslexia. World boxing titles. During his suspension from , Ali became an activist and toured around the world speaking to civil rights organizations and anti-war groups. Croke Park , Dublin , Ireland. But get used to me — black, confident, cocky; my name, not yours; my religion, not yours; my goals, my own. In winning this fight at the age of 22, Clay became the youngest boxer to take the title from a reigning heavyweight champion. Ali later used the "accupunch" to knockout Richard Dunn in Retrieved December 27, In , the Associated Press reported that Ali was tied with Babe Ruth as the most recognized athlete, out of over dead or living athletes, in America. His reflexes, while still superb, were no longer as fast as they had once been. Following this win, on July 27, , Ali announced his retirement from boxing. After his death she again made passionate appeals to be allowed to mourn at his funeral. -

Bedside 11 12 03.Indd

Wandsworth SocietetyÈ ˘ ˘˘ ˘˘˘ ˘˘˘˘ ˘˘˘˘˘ ˘˘˘˘˘˘ ˘˘˘˘˘˘˘ ˘˘˘˘˘˘˘˘ ˘˘˘˘˘˘˘˘˘ ˘˘˘˘˘˘˘˘˘˘ The Bedside 1971 - FORTY YEARS ON - 2011 Mistletoe istletoe, forming as numerous illustrations show, it was remembered that a vile- evergreen clumps on the association of kissing and tasting tea, made from mistletoe apple and many other mistletoe was well established by which grew on hawthorn, was broad-leaved trees, Victorian times. used to treat measles. Other is a strange plant. It people have collected informa- Mabsorbs water and nutrients from tion on mistletoe being used to its host trees, but as it has chlo- treat hysteria in Herefordshire and rophyll it is able to make its own prevent strokes in Essex. food. If sufficiently mature seeds are Pliny the Elder in the first century used mistletoe can be easily A.D. described Druids in France grown on apple trees. Seeds cutting mistletoe from oak trees extracted from Christmas mistle- in a ritual which involved golden toe are not mature, so it’s neces- sickles, dressing in white cloaks, sary to collect berries in April, slaughtering white bulls. Because squeeze out the seeds and insert of this, mistletoe was considered them in a notch cut in the tree’s to be a pagan plant and banned bark. After a couple of months from churches. small plants emerge, but many of these seem to die within a Mistletoe was associated with year. Survivors grow rapidly and Christmas since the mid-17th live for many years. However, century. By the 19th century this mistletoe produces female and association was well established, male flowers on different plants, and people who had mistletoe- and although I’ve left a trail of bearing trees on their land were mistletoe plants behind me as I’ve bothered by people who raided The situation is complicated by moved around, I haven’t yet man- them. -

Las Vegas Optic, 03-06-1913 the Optic Publishing Co

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Las Vegas Daily Optic, 1896-1907 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 3-6-1913 Las Vegas Optic, 03-06-1913 The Optic Publishing Co. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/lvdo_news Recommended Citation The Optic Publishing Co.. "Las Vegas Optic, 03-06-1913." (1913). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/lvdo_news/1937 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Las Vegas Daily Optic, 1896-1907 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 j'1 CwLw .Z3 p Weather Forecast '(C PaiV Maxim Rain tonight or Fri-- , Common sense; the day; somewhat least fashionable cooler. thing. EXCLUSIVE ASSOCIATED FJREQgB LEASED WIRE TELEGRAPH SERVICE VOL. XXXIV. NO. 99. LAS VEGAS DAmLY CPTIC.THURSDAY, MARCH 6, 1913. CITY EDITION During the night volunteers arrived curred, it is said, near the Peninsula REVOLT AGAINST in great numbers In answer to the DARIN MAKES A WISHES NATIO JANINA GIVES UP of Hagion Oros in .the Aegean Sea. FOREIGN P0L1C a i peal of the state congress for for- From this it would appear that the ces to combat any intrusion of Huer- transports were proceeding not to ta troops in the border state. TO BUY LAND A Scutari but to Gallipoll, where it was WILL NOT BE HUERTA 0 ROWS Work on fortifications about the PLEA FOR HIS AFfElf LONG proposed some time ago by the Bal- city continued throughout the night, kan allies to make a flank attack on ammunition was assembled and all the Turkish troops defending the CHANGED RAPIDLY made ready for the expected assault LIBERTY GRANTS FIGHT Dardanelles. -

They Must Fall Datasheet

Image not found or type unknown Image not found or type unknown TITLE INFORMATION Tel: +44 (0) 1394 389950 Email: [email protected] Web: https://www.accartbooks.com/uk Published 12th Oct 2020 Image not found or type unknown They Must Fall Muhammad Ali and the Men He Fought Photographs by Michael Brennan Contributions by Michael Brennan Introduction by Jimmy Breslin Foreword by Simon van Booy ISBN 9781788840187 Publisher ACC Art Books Binding Hardback Territory World Size 250 mm x 250 mm Pages 240 Pages Illustrations 20 colour, 130 b&w Price £35.00 Exclusive never-before-seen photos of Ali and other stars of the '70s boxing scene Celebrates one of the greatest heavyweight champions of all time, as well as those who went up against him in the ring - including Alvin Lewis, Alex Miteff, Buster Mathis, George Chuvalo, Charlie Powell, Chuck Wepner, Donnie Fleeman, Duke Sabedong, Floyd Patterson, George Foreman, George Logan, Henry Cooper, Herb Siler, Jimmy Robinson, Jimmy Young, Joe Bugner, Joe Frazier, Ken Norton, LaMar Clark, Larry Holmes, Leon Spinks, Sonny Liston, Richard Dunn, Tony Esperti, Tunney Hunsaker, Willi Besmanoff This edition also includes a special introductory essay by the late, great Jimmy Breslin They Must Fall: Muhammad Ali and the Men He Fought features powerful and often moving images and stories of Muhammad Ali and the men he fought in the ring, by award-winning photographer Michael Brennan. “Around 1978, I had been in Houston, Texas photographing former Ali opponent George Foreman who had then reinvented himself as a roadside preacher. On the plane back to NYC, I thought, ‘If that’s what George is doing, I wonder what the rest of his opponents are up to?’ I set out to track down as many of the old guys as I could find.” Brennan spent decades locating Ali’s former opponents to discover what had become of them. -

Exeter Blitz for Adobe

Devon Libraries Exeter Blitz Factsheet 17 On the night of 3 rd - 4 th of May 1942, Exeter suffered its most destructive air raid of the Second World War. 160 high explosive bombs and 10,000 incendiary devices were dropped on the city. The damage inflicted changed the face of the city centre forever. Exeter suffered nineteen air raids between August 1940 and May 1942. The first was on the night of 7 th – 8 th of August 1940, when a single German bomber dropped five high explosive bombs on St. Thomas. Luckily no one was hurt and the damage was slight. The first fatalities were believed to have been in a raid on 17 th September 1940, when a house in Blackboy Road was destroyed, killing four boys. In most of the early raids it is likely that the city was not the intended target. The Luftwaffe flew over Exeter on its way towards the industrial cities to the north. It is possible that these earlier attacks on Exeter were caused by German bombers jettisoning unused bombs on the city when returning from raiding these industrial targets. It was not until the raids of 1942 that Exeter was to become the intended target. The town of Lubeck is a port on the Baltic; it had fine medieval architecture reflecting its wealth and importance. Although it was used to supply the German army and had munitions factories on the outskirts of the town, it was strategically unimportant. The bombing of this town on the night of 28 th – 29 th March on the orders of Bomber Command is said to be the reason why revenge attacks were carried out on ‘some of the most beautiful towns in England’. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

2007 Lnstim D'hi,Stoire Du Temp

WORLD "TAR 1~WO STlIDIES ASSOCIATION (formerly American Committee on the History ofthe Second World War) Mark P. l'arilIo. Chai""an Jona:han Berhow Dl:pat1menlofHi«ory E1izavcla Zbeganioa 208 Eisenhower Hall Associare Editors KaDsas State University Dct>artment ofHistory Manhattan, Knnsas 66506-1002 208' Eisenhower HnJl 785-532-0374 Kansas Stale Univemty rax 785-532-7004 Manhattan, Kansas 66506-1002 parlllo@,'<su.edu Archives: Permanent Directors InstitlJle for Military History and 20" Cent'lly Studies a,arie, F. Delzell 22 J Eisenhower F.all Vandcrbijt Fai"ersity NEWSLETTER Kansas State Uoiversit'j Manhattan, Kansas 66506-1002 Donald S. Detwiler ISSN 0885·-5668 Southern Ulinoi' Va,,,,,,,sity The WWT&« is a.fIi!iilI.etf witJr: at Ccrbomlale American Riston:a1 A."-'iociatioG 400 I" Street, SE. T.!rms expiring 100(, Washingtoo, D.C. 20003 http://www.theah2.or9 Call Boyd Old Dominio" Uaiversity Comite internationa: dlli.loire de la Deuxii:me G""",, Mondiale AI"".nde< CochrnIl Nos. 77 & 78 Spring & Fall 2007 lnstiM d'Hi,stoire du Temp. PreSeDt. Carli5te D2I"n!-:'ks, Pa (Centre nat.onal de I. recberche ,sci,,,,tifiqu', [CNRSJ) Roj' K. I'M' Ecole Normale S<rpeneure de Cach411 v"U. Crucis, N.C. 61, avenue du Pr.~j~'>Ut WiJso~ 94235 Cacllan Cedex, ::'C3nce Jolm Lewis Gaddis Yale Universit}' h<mtlJletor MUitary HL'mry and 10'" CenJury Sllldie" lIt Robin HiRbam Contents KaIUa.r Stare Universjly which su!'prt. Kansas Sl.ll1e Uni ....ersity the WWTSA's w-'bs;te ":1 the !nero.. at the following ~ljjrlrcs:;: (URL;: Richa.il E. Kaun www.k··stare.eDu/his.tD.-y/instltu..:..; (luive,.,,)' of North Carolw. -

THE JUDICIARY OP TAP Oupcrior COURTS 1820 to 1968 : A

THE JUDICIARY OP TAP oUPCRIOR COURTS 1820 to 1968 : A SOCIOLOGICAL STUDY A tiiesis presented for the lAPhilo degree University of London. JENNIFER MORGAl^o BEDFORD COLLEGE, 1974. ProQuest Number: 10097327 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10097327 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Aijstract This study is an attempt to construct o social profile of the Juoiciary of the superior courts uurin^ the period 1 8 20-1 9 6 8. The analyses cover a vio: raepe of characteristics iacluuiap parental occupation, schooling, class op degree, ape of call to toæ luu' ^aa ape at appolnt^/^ent to tue -each. These indices are used to deter..line how far opportunities for recruitment to the dench lave seen circumscribed by social origin, to assess the importance of academic pualificaticns and vocational skills in the achievement of professional success and to describe the pattern of the typical judicial career. The division of the total population of judges into four cohorts, based on the date of their initial appointment to the superior courts, allows throughout for historical comparison, demonstrating the major ^oints of change and alsu underlining the continuities in tne composition of the Bench during the period studied. -

Dislocation and Children's Relationships with Their Peers and Parents in Children's Fiction Set During the Second World War

Dislocation and children's relationships with their peers and parents in children's fiction set during the Second World War. by Timothy Johnstone, B.A. A Masters Dissertation, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Masters of Arts degree of the Loughborough University of Technology. September 1995 Supervisor: Professor M. Evans, BA, MBA CNAA, PhD, PGCE, ALA, MIInfSc. Department of Information and Library Studies. ., © T. Johnstone, 1995. Abstract This dissertation looks at the treatment of dislocation and children's relationships with their parents and peers in novels written for children about the Second World War, in order to identify what are the dominant themes which the authors develop. The first chapter deals with evacuation: its unpopularity and the problems it caused and the deVelopment of themes which show fictional evacuees facing those problems with optimism and their successful adaptation to a new environment. Chapter 11 shows how the situation of refugees in wartime Britain was not approached ill _ children's literature until a decade after the war, when stories containing themes of optimism in adversity, self-discovery, exposure of prejudice and supportive families began to appear. In chapter Ill, the differences the war brought to parent and child relationships are identified, especially their portrayal in a wave of children's novels based upon the writers' wartime, childhood memories, which again develop themes of readjustment and the overcoming of adversity, particularly through the caring -

Bat-Bec Bat-Bec

• 322 BAT-BEC LONDON COUNTY SUBURBS BAT-BEC • Batten GeorgeBeckettM.D.phys.&surg. 2 Underhill rd.E.Dulwich SE Baumann John, baker, 75 Elthorne road, Hornsl"y RiseN Beau John, confectioner, 133 Canterbury road, Kilbum NW -'1' N 738 Sydenham & see Batten, Stew art & Oarpmael BanmberEmma(Mrs.),plumber,4 Gains borough rd. Hckny. WickNE Bean Louis, tailor, 61 St. Jame>' place, Plumstead SE Batten John, milliner, 142 Trafalgar rond, Greenwich SE Bauml Richard, apartments, 4 Parliament hill, Hampstead NW Bean Louis Constantine, phys. & surg.l8 & 4S Falcon rd. Bttersea SW Batten Richard, butcher, 98 Mitcham lane, Btreatham SW Bause Ernest William, confectioner, 349 Brockley rd. Brock.ley SE !3":J.·o l'loo '''"· hn•l·ler, 110 .Bicker~teth road, Tooting- SW Batten Thowas, ticket writer. 42 Bel1enden road, Peckham SE Baverstock Louis, printer, see Parsons & Baverstock Rcaue Genrge, insnmnce agent, 147 Mildenha.ll rd. Low.Cbpton NB Batten William B. patent medicine proprietor, 431 Brixton road SW Bawden Frederick, grocer, 19IA & l!HB, Munster road,Fulham SW 13eanes E. & Co. Ltd. Falcon chemical works, 82 Wallia road, Batterhury Thomas, district surveyor, 15 Griffin road, Plumstead BE BaxWilliam Jn. & Son, timber mers. 56 Priory grove, S.La.mbeth SW Hacknev Wick NE-T N 671 East Batterham Alfred Jas. drug stores, 16 Fonthill rd. Finsbury Park N Bax Kate (Mill.), dressmaker, 33 L<m•anne road. Peckham SE Beaney Fredk.wood turner,48A.Rye la.Pckhm SE -TN 414New0ross Battersea Borough Council (Wm. Ma.rcus Wilkins, town clerk ; Ba.xter & Sons, newsagents, 47 Artillery place, Woolwicb SE BP.ru1ey Frederick Charles, wood turner, 20 Elm J.,'l'O.