JOHN PLUMB 15 Plumb 1226 15/11/2004 10:41 Page 269

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sir Andrew J. Wiles

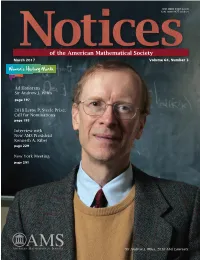

ISSN 0002-9920 (print) ISSN 1088-9477 (online) of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 Volume 64, Number 3 Women's History Month Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Wiles page 197 2018 Leroy P. Steele Prize: Call for Nominations page 195 Interview with New AMS President Kenneth A. Ribet page 229 New York Meeting page 291 Sir Andrew J. Wiles, 2016 Abel Laureate. “The definition of a good mathematical problem is the mathematics it generates rather Notices than the problem itself.” of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 FEATURES 197 239229 26239 Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Interview with New The Graduate Student Wiles AMS President Kenneth Section Interview with Abel Laureate Sir A. Ribet Interview with Ryan Haskett Andrew J. Wiles by Martin Raussen and by Alexander Diaz-Lopez Allyn Jackson Christian Skau WHAT IS...an Elliptic Curve? Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof by by Harris B. Daniels and Álvaro Henri Darmon Lozano-Robledo The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles by Christopher Skinner In this issue we honor Sir Andrew J. Wiles, prover of Fermat's Last Theorem, recipient of the 2016 Abel Prize, and star of the NOVA video The Proof. We've got the official interview, reprinted from the newsletter of our friends in the European Mathematical Society; "Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof" by Henri Darmon; and a collection of articles on "The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles" assembled by guest editor Christopher Skinner. We welcome the new AMS president, Ken Ribet (another star of The Proof). Marcelo Viana, Director of IMPA in Rio, describes "Math in Brazil" on the eve of the upcoming IMO and ICM. -

Annotated Guide to Secondary Literature on Medieval

THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY HIEU 390 Constantin Fasolt Fall 1999 TU TH 11:00-12:15 POLITICS, SOCIETY, AND SOCIAL THOUGHT IN EUROPE I: 400-1300 A GUIDE TO READING This guide is designed to explain my choice of readings for this course and to lead you to further readings appropriate for you, depending on how much or how little you already know about European history in general and the history of European political thought in particular. It is divided into three parts. The first part deals with general works, background information, and introductory readings of various sorts. The second part is arranged, roughly speaking, according to the topics that will be addressed in the course. The third part is a reference section, in which I simply list the most important books and articles and offer a few comments on some of them. I wrote this guide mostly for beginners. I have therefore placed special emphasis on introductory works and have tried to limit myself to works in English. But where it seemed useful or necessary I have not hesitated to mention works written in other languages. I have also made a special effort to single out books and articles that have struck me as especially telling or informative, never mind how difficult or advanced they may be. I hope that this procedure will make it easy for you to start reading where it will be most profitable for you, and to keep reading for a long time to come once your interest has been awakened. Table of Contents Part one: General works __________________________________________________ 3 A. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

Books Added to Benner Library from Estate of Dr. William Foote

Books added to Benner Library from estate of Dr. William Foote # CALL NUMBER TITLE Scribes and scholars : a guide to the transmission of Greek and Latin literature / by L.D. Reynolds and N.G. 1 001.2 R335s, 1991 Wilson. 2 001.2 Se15e Emerson on the scholar / Merton M. Sealts, Jr. 3 001.3 R921f Future without a past : the humanities in a technological society / John Paul Russo. 4 001.30711 G163a Academic instincts / Marjorie Garber. Book of the book : some works & projections about the book & writing / edited by Jerome Rothenberg and 5 002 B644r Steven Clay. 6 002 OL5s Smithsonian book of books / Michael Olmert. 7 002 T361g Great books and book collectors / Alan G. Thomas. 8 002.075 B29g Gentle madness : bibliophiles, bibliomanes, and the eternal passion for books / Nicholas A. Basbanes. 9 002.09 B29p Patience & fortitude : a roving chronicle of book people, book places, and book culture / Nicholas A. Basbanes. Books of the brave : being an account of books and of men in the Spanish Conquest and settlement of the 10 002.098 L552b sixteenth-century New World / Irving A. Leonard ; with a new introduction by Rolena Adorno. 11 020.973 R824f Foundations of library and information science / Richard E. Rubin. 12 021.009 J631h, 1976 History of libraries in the Western World / by Elmer D. Johnson and Michael H. Harris. 13 025.2832 B175d Double fold : libraries and the assault on paper / Nicholson Baker. London booksellers and American customers : transatlantic literary community and the Charleston Library 14 027.2 R196L Society, 1748-1811 / James Raven. -

Principle and Politics in the New History of Originalism

Digital Commons @ Georgia Law Scholarly Works Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2017 Principle and Politics in the New History of Originalism Logan E. Sawyer III Associate Professor of Law University of Georgia, [email protected] University of Georgia School of Law Research Paper Series Paper No. 2017-18 Repository Citation Logan E. Sawyer III, Principle and Politics in the New History of Originalism , 57 Am. J. Legal Hist. 198 (2017), Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/fac_artchop/1326 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Georgia Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Georgia Law. Please share how you have benefited from this access For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA SCHOOL OF LAW RESEARCH PAPER SERIES Paper No. 2017-18 May 2017 PRINCIPLE AND POLITICS IN THE NEW HISTORY OF ORIGINALISM AM. J. LEGAL. HIST. (forthcoming). LOGAN E. SAWYER III Associate Professor of Law University of Georgia School of Law [email protected] This paper can be downloaded without charge from the Social Science Research Network electronic library at https://ssrn.com/abstract=2933746 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2933746 PRINCIPLE AND POLITICS in The New History of Originalism The emergence of a new form of originalism has sparked an interest in the theory’s past that is particularly welcome as developments on the Supreme Court and in the Republican Party unsettle the theory’s place in American law and politics. -

The Conceptualization of Time and Space in the Memory Theatre of G Camillo

Nordisk Museologi 2003 • 1, s. 51–70 The conceptualization of time 51 and space in the memory theatre of giulio camillo (1480?–1544)1 Anne Aurasmaa In the 17th century collections became ideally more or less the presence of all things material. Interest leaned towards the mundane and the common and collecting became a gathering of everything. This trend can already be seen to some extent in the natural history collections of the 16th century. As a counterbalance to this I would like to put forward in this paper the idea that the 16th century collections pictured the whole universe as a construction combining time and space. It was not the intention just to fill rooms with collected material examples but to present the phenomena by showing their boundaries and to help the spectator to understand the building blocks of the universal hierarchy. The theatrum mundi – or curiosity cabinet, as 16th century collections are more commonly referred to – was conceived as a presence of all that existed in one place. Instead of collecting everything, and claiming that such a collection would represent the world as it is (or as it can be perceived by the senses), rhetorical themes, abstract ideas and universal structures were visualized by means of displaying the strangest objects from the most faraway places. The function of such displays was to bridge the gap between the universal logos2 and the human logos. Logos meaning reason and structure is the opposite of myth and personal sensory experience and as such includes thinking, speech, relations and regularities. The concept can be used both in reference to universal order and to the faculties of the human mind. -

Further Particulars

CHRIST’S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE JH PLUMB COLLEGE LECTURESHIP AND FELLOWSHIP IN HISTORY FURTHER PARTICULARS Teaching at Cambridge University is provided by the University and also by the Colleges. The majority of College Fellows are holders of University posts, taking on additional College responsibilities for which they usually receive extra remuneration. However, from time to time, Cambridge Colleges make appointments to College Lectureships. When appointed, College Lecturers not only provide core teaching for the College (or sometimes for other Colleges under swap arrangements) but may also be asked to act as Directors of Studies or take on other College offices or duties as appropriate. These Fellows may, if the opportunity arises, also teach for the University on occasional lecture courses, for extra remuneration. College Lectureships at Christ’s College are intended to provide an opportunity to an individual at the beginning of his or her academic career to develop teaching skills, a publication record and other academic activity with a view to obtaining a University appointment in Cambridge or elsewhere. They are offered for a fixed term of four years, which will not be renewed or extended. College Teaching College teaching takes the form of small group teaching (referred to as supervisions) each week, usually in groups of one or two. There are two Terms of eight weeks (Michaelmas and Lent); the third Term (Easter Term) has four weeks of teaching and three weeks set aside for University examinations. The successful candidate would be expected to supervise at least 120 hours per year for the College, equivalent to an average of six hours per week in Full Term. -

Historical Argument and Practice Bibliography for Lectures 2019-20

HISTORICAL ARGUMENT AND PRACTICE BIBLIOGRAPHY FOR LECTURES 2019-20 Useful Websites http://www.besthistorysites.net http://tigger.uic.edu/~rjensen/index.html http://www.jstor.org [e-journal articles] http://www.lib.cam.ac.uk/ejournals_list/ [all e-journals can be accessed from here] http://www.historyandpolicy.org General Reading Ernst Breisach, Historiography: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983) R. G. Collingwood, The Idea of History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1946) Donald R. Kelley, Faces of History: Historical Inquiry from Herodotus to Herder (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998) Donald R. Kelley, Fortunes of History: Historical Inquiry from Herder to Huizinga (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003) R. J. Evans, In Defence of History (2nd edn., London, 2001). E. H. Carr, What is History? (40th anniversary edn., London, 2001). Forum on Transnational History, American Historical Review, December 2006, pp1443-164. G.R. Elton, The Practice of History (2nd edn., Oxford, 2002). K. Jenkins, Rethinking History (London, 1991). C. Geertz, Local Knowledge (New York, 1983) M. Collis and S. Lukes, eds., Rationality and Relativism (London, 1982) D. Papineau, For Science in the Social Sciences (London, 1978) U. Rublack ed., A Concise Companion to History (Oxford, 2011) Q.R.D. Skinner, Visions of Politics Vol. 1: Regarding Method (Cambridge, 2002) David Cannadine, What is History Now, ed. (Basingstoke, 2000). -----------------------INTRODUCTION TO HISTORIOGRAPHY---------------------- Thu. 10 Oct. Who does history? Prof John Arnold J. H. Arnold, History: A Very Short Introduction (2000), particularly chapters 2 and 3 S. Berger, H. Feldner & K. Passmore, eds, Writing History: Theory & Practice (2003) P. -

Crisis of Rhetoric Launch Event: Committee Room G, House of Lords, 15Th October 2019

Crisis of Rhetoric Launch Event: Committee Room G, House of Lords, 15th October 2019 Event Transcript Speaker names and abbreviations: Dr Henriette van der Blom (HvdB), Prof. Alan Finlayson (AF), Phil Collins (PC), Prof. Mary Beard (MB), John Vice (JV). [??? Indicates indecipherable speech on the recording]. HvdB: Welcome, everybody, we should probably get started. Thank you so much to all of you for coming through all the security, all the barricades at Parliament, we are very pleased to see you here. My name is Henriette van der Blom, I’m a Senior Lecturer in Ancient History at the University of Birmingham and I am the principal investigator of the Crisis of Rhetoric research project sponsored by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, together with my colleague Professor Alan Finlayson, Professor of Politics at the University of East Anglia. We’ve been conducting this project for a couple of years now and this is the finale that you’ve been invited to come and share in, where we are launching the findings that you have all received on your seat. I should also say that this booklet is available in PDF on the project website, which you will see on the inside cover, page 3 – one of the text boxes. So, if you want it in PDF, you can go and download it for free, share it with friends, colleagues as you wish. Now we are very pleased to be here because the whole idea of this project was to find out what’s going on with political speech today and to join up two groups who perhaps don’t speak often enough with each other; that is, our own world of academia with practitioners: speakers, orators, speech writers and everybody who help the speakers prepare and deliver the speeches in as effectful and thoughtful manners as possible. -

The Essential Turing: Seminal Writings in Computing, Logic, Philosophy, Artificial Intelligence, and Artificial Life: Plus the Secrets of Enigma

The Essential Turing: Seminal Writings in Computing, Logic, Philosophy, Artificial Intelligence, and Artificial Life: Plus The Secrets of Enigma B. Jack Copeland, Editor OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS The Essential Turing Alan M. Turing The Essential Turing Seminal Writings in Computing, Logic, Philosophy, Artificial Intelligence, and Artificial Life plus The Secrets of Enigma Edited by B. Jack Copeland CLARENDON PRESS OXFORD Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Taipei Toronto Shanghai With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan South Korea Poland Portugal Singapore Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © In this volume the Estate of Alan Turing 2004 Supplementary Material © the several contributors 2004 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2004 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. -

Joan Clarke at Station X

Joan Clarke at Station X Before Joan Clarke worked at Bletchley Park’s Hut 8, she already knew Alan Turing. He was a friend of Joan’s brother. A very intelligent young woman, Joan studied mathematics at Cambridge University’s Newnham College. Gordon Welchman, who was working for the Government Code & Cypher School in the late 1930s, recruited Joan to work at Bletchley Park. He’d been her Geometry supervisor at Cambridge. At the time, women did not typically fill important jobs at Bletchley Park (or anywhere else throughout Britain). So ... at the beginning of her work at Station X ... Joan filled a clerical slot. It took very little time, however, for Joan to get her “own table” inside Hut 8. This promotion effectively placed her on Turing’s code-breaking team. Not only did Joan do great work at Bletchley, by 1944 she was deputy-head of the Hut-8 team. During the early part of her work at Station X, Joan had been promoted to a “Linguist,” even though she wasn’t fluent in other languages. (It was just a way for her to receive better pay for her work.) She once answered a questionnaire with these words: Grade: Linguist, Languages: None. When she first became a Hut-8 code breaker, Joan worked with Alan Turing, Tony Kendrick and Peter Twinn. Their actual work focused on breaking Germany’s Naval Enigma code (which the Station X workers had codenamed “Dolphin”). Joan and Alan Turing became very close friends and, in 1941, the head of Hut 8 asked his friend to become his wife. -

Hobbes and Republican Liberty Quentin Skinner Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88676-5 - Hobbes and Republican Liberty Quentin Skinner Frontmatter More information Hobbes and Republican Liberty Quentin Skinner is one of the foremost historians in the world, and in Hobbes and Republican Liberty he offers a dazzling comparison of two rival theories about the nature of human liberty. The first originated in classical antiquity, and lay at the heart of the Roman republican tradition of public life. It flowered in the city-republics of Renaissance Italy, and has been central to much recent discussion of republicanism among contemporary political theorists. Thomas Hobbes was the most formidable enemy of this pattern of thought, and his attempt to discredit it constitutes a truly epochal moment in the history of Anglophone political thought. Professor Skinner shows how Hobbes’s successive efforts to grapple with the question of human liberty were deeply affected by the claims put forward by the radical and parliamentarian writers in the course of the English civil wars, and by Hobbes’s sense of the urgent need to counter them in the name of peace. Skinner approaches Hobbes’s political theory not simply as a general system of ideas but as a polemical intervention in the conflicts of his time, and he shows that Leviathan, the greatest work of political philosophy ever written in English, reflects a substantial change in the character of Hobbes’s moral thought, responding very specifically to the political needs of the moment. As Professor Skinner says, seething polemics always underlie the deceptively smooth surface of Hobbes’s argument. Hobbes and Republican Liberty is an extended essay that develops several of the themes announced by Quentin Skinner in his famous inaugural lecture on Liberty before Liberalism of 1998.