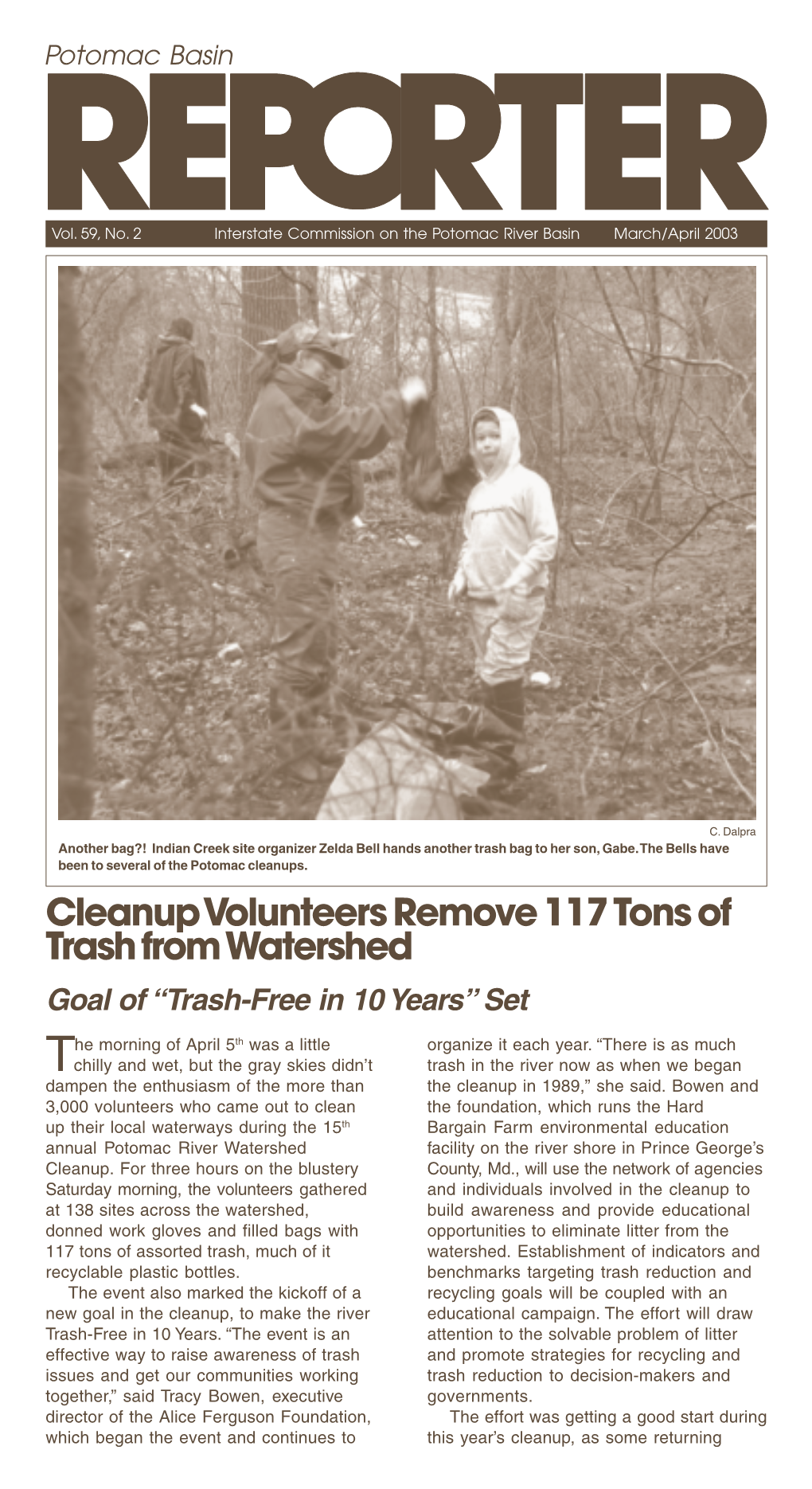

Cleanup Volunteers Remove 117 Tons of Trash from Watershed Goal of “Trash-Free in 10 Years” Set

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title 26 Department of the Environment, Subtitle 08 Water

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION Chapters 01-10 2 26.08.01.00 Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION Chapter 01 General Authority: Environment Article, §§9-313—9-316, 9-319, 9-320, 9-325, 9-327, and 9-328, Annotated Code of Maryland 3 26.08.01.01 .01 Definitions. A. General. (1) The following definitions describe the meaning of terms used in the water quality and water pollution control regulations of the Department of the Environment (COMAR 26.08.01—26.08.04). (2) The terms "discharge", "discharge permit", "disposal system", "effluent limitation", "industrial user", "national pollutant discharge elimination system", "person", "pollutant", "pollution", "publicly owned treatment works", and "waters of this State" are defined in the Environment Article, §§1-101, 9-101, and 9-301, Annotated Code of Maryland. The definitions for these terms are provided below as a convenience, but persons affected by the Department's water quality and water pollution control regulations should be aware that these definitions are subject to amendment by the General Assembly. B. Terms Defined. (1) "Acute toxicity" means the capacity or potential of a substance to cause the onset of deleterious effects in living organisms over a short-term exposure as determined by the Department. -

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5 DATABASE DESIGN DOCUMENTATION AND DATA DICTIONARY 1 June 2013 Prepared for: United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, Maryland 21403 Prepared By: Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 Prepared for United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, MD 21403 By Jacqueline Johnson Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin To receive additional copies of the report please call or write: The Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 301-984-1908 Funds to support the document The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.0; Database Design Documentation And Data Dictionary was supported by the US Environmental Protection Agency Grant CB- CBxxxxxxxxxx-x Disclaimer The opinion expressed are those of the authors and should not be construed as representing the U.S. Government, the US Environmental Protection Agency, the several states or the signatories or Commissioners to the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin: Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia or the District of Columbia. ii The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.5 TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. -

Maryland's 2016 Triennial Review of Water Quality Standards

Maryland’s 2016 Triennial Review of Water Quality Standards EPA Approval Date: July 11, 2018 Table of Contents Overview of the 2016 Triennial Review of Water Quality Standards ............................................ 3 Nationally Recommended Water Quality Criteria Considered with Maryland’s 2016 Triennial Review ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Re-evaluation of Maryland’s Restoration Variances ...................................................................... 5 Other Future Water Quality Standards Work ................................................................................. 6 Water Quality Standards Amendments ........................................................................................... 8 Designated Uses ........................................................................................................................... 8 Criteria ....................................................................................................................................... 19 Antidegradation.......................................................................................................................... 24 2 Overview of the 2016 Triennial Review of Water Quality Standards The Clean Water Act (CWA) requires that States review their water quality standards every three years (Triennial Review) and revise the standards as necessary. A water quality standard consists of three separate but related -

2014 Virginia Freshwater Fishing & Watercraft Owner’S Guide

2014 Virginia Freshwater Fishing & Watercraft Owner’s Guide Free Fishing Days: June 6–8, 2014 National Safe Boating Week: May 17–23, 2014 www.HuntFishVA.com Table of Contents Freshwater Fishing What’s New For 2014................................................5 Fishing License Information and Fees ....................................5 Commonwealth of Virginia Freshwater/Saltwater License Lines on Tidal Waters .........................8 Terry McAuliffe, Governor Reciprocal Licenses .................................................8 General Freshwater Fishing Regulations ..................................9 Department of Game Game/Sport Fish Regulations.........................................11 Creel and Length Limit Tables .......................................12 and Inland Fisheries Trout Fishing Guide ................................................18 Bob Duncan, Executive Director 2014 Catchable Trout Stocking Plan...................................20 Members of the Board Special Regulation Trout Waters .....................................22 Curtis D. Colgate, Chairman, Virginia Beach Fish Consumption Advisories .........................................26 Ben Davenport, Vice-Chairman, Chatham Nongame Fish, Reptile, Amphibian, and Aquatic Invertebrate Regulations........27 David Bernhardt, Arlington Let’s Go Fishing Lisa Caruso, Church Road Fish Identification and Fishing Information ...............................29 Charles H. Cunningham, Fairfax Public Lakes Guide .................................................37 Garry L. Gray, -

Northumberland County, Virginia Shoreline Inventory Report

W&M ScholarWorks Reports 12-2014 Summary Tables: Northumberland County, Virginia Shoreline Inventory Report Marcia Berman Virginia Institute of Marine Science Karinna Nunez Virginia Institute of Marine Science Sharon Killeen Virginia Institute of Marine Science Tamia Rudnicky Virginia Institute of Marine Science Julie Bradshaw Virginia Institute of Marine Science See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/reports Part of the Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Recommended Citation Berman, M.R., Nunez, K., Killeen, S., Rudnicky, T., Bradshaw, J., Duhring, K., Stanhope, D., Angstadt, K., Tombleson, C., Procopi, A., Weiss, D. and Hershner, C.H. 2014. Northumberland County, Virginia - Shoreline Inventory Report: Methods and Guidelines, SRAMSOE no.444, Comprehensive Coastal Inventory Program, Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William and Mary, Gloucester Point, Virginia, 23062 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reports by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Marcia Berman, Karinna Nunez, Sharon Killeen, Tamia Rudnicky, Julie Bradshaw, Karen Duhring, David Stanhope, Kory Angstadt, Christine Tombleson, Alexandra Procopi, David Weiss, and Carl Hershner This report is available at W&M ScholarWorks: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/reports/784 -

Northumberland County Tidal Marsh Inventory

W&M ScholarWorks Reports 2-1975 Northumberland County Tidal Marsh Inventory Gene M. Silberhorn Virginia Institute of Marine Science Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/reports Part of the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Silberhorn, G. M. (1975) Northumberland County Tidal Marsh Inventory. Special Report in Applied Marine Science and Ocean Engineering No. 58. Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William and Mary. https://doi.org/10.21220/V5Z13J This Report is brought to you for free and open access by W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reports by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NORTHUMBERLAND COUNTY TIDAL MARSH INVENTORY Special Report No. 58 in Applied Marine Science and Ocean Engineering G. M. Silberhorn Virginia Institute of Marine Science Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062 Dr. William J. Hargis, Jr., Director February 1975 Acknowledgments The publication and distribution of this report have been provided by the Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of Coastal Zone Management, Grant No. 04-5-158-5001. The author wishes to thank Dr. William J. Hargis, Jr., Dr. Michael E. Bender, Mr. John Pleasants, Col. George Dawes and Mr. Kenneth Moore for their constructive criticism and suggestions which have assisted in the development of this publication. Thanks also to Col. Dawes and Mr. Joseph Dalton, Chairman of the Northumberland County Wetlands Board for their assistance in the field. Also, information regarding fish populations in small marshes was provided by Mr. Carl Hershner, for which I am very grateful. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

(Rev. 1U-9D) NPS Form 10-900 OMB NO.1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use In llori~inatlngor requestingdctcrminat~onsfor indiv~dualproperties and di:;uicts. See instmclions In How toConlpletc theNational Register of H~siorlcPlaces Registration Form (National Kep~stcrBullcr~n 16A). Complete each itemby marking "x" intheappropriateboxor by enterlng the information requeried Ilariy item does not apply to the propeny being ducumented, cnter "NIA" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural class~fication,~natcrials, and arras of significancc, enter only categories and subcategories from the ~nstructions Place additional entries and narrative items on conllllualton sheets (NPSFonn 10-900a) Usc a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete aH items. I. Name of Property historic name Kinsate Historic District other nameslsite number VDHR #096-0090 2. Location street & number Area inctudine parts of Bank Street, Great House, Kinsale, Plain View. and Kinsale Bridpe roads; Cat Nap and Yeocomico lanes, Pier Place, Sipournev Drive. an:dSteamboat Landinp. not for publication N/A city or town Kinsale vicinity state Virginia codexcounty Westmoreland code - t93 Zip 22488 3. StatelFederal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act 01' 1986,as amended, 1 hereby cerlify that this -X- nomination -request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties inthe National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professionaI requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property -X- meets -does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

VIRGINIA WORKING WATERFRONT MASTER PLAN Guiding Communities in Protecting, Restoring and Enhancing Their Water-Dependent Commercial and Recreational Activities

VIRGINIA WORKING WATERFRONT MASTER PLAN Guiding communities in protecting, restoring and enhancing their water-dependent commercial and recreational activities JULY 2016 This planning report, Task 92 was funded by the Virginia Coastal Zone Management Program at the Department of Environmental Quality through Grant #NA15NOS4190164 of the U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, under the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of Commerce, NOAA, or any of its subagencies. 1 Table of Contents I. Introduction ..................................................................................................... 4 II. Acknowledgements ......................................................................................... 6 III. Executive Summary ......................................................................................... 8 IV. Working Waterfronts – State of the Commonwealth ................................. 20 V. Northern Neck Planning District Commission ............................................. 24 A. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 25 B. History of Working Waterfronts in the Region .......................................................................... 26 C. Current Status of Working Waterfronts in the Region............................................................. -

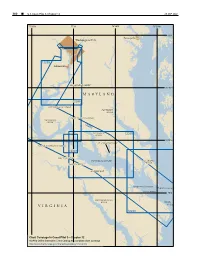

M a R Y L a N D V I R G I N

300 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 3, Chapter 12 26 SEP 2021 77°20'W 77°W 76°40'W 76°20'W 39°N Annapolis Washington D.C. 12289 Alexandria PISCATAWAY CREEK 38°40'N MARYLAND 12288 MATTAWOMAN CREEK PATUXENT RIVER PORT TOBACCO RIVER NANJEMOY CREEK 12285 WICOMICO 12286 RIVER 38°20'N ST. CLEMENTS BAY UPPER MACHODOC CREEK 12287 MATTOX CREEK POTOMAC RIVER ST. MARYS RIVER POPES CREEK NOMINI BAY YEOCOMICO RIVER Point Lookout COAN RIVER 38°N RAPPAHANNOCK RIVER Smith VIRGINIA Point 12233 Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 3—Chapter 12 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 3, Chapter 12 ¢ 301 Chesapeake Bay, Potomac River (1) This chapter describes the Potomac River and the above the mouth; thence the controlling depth through numerous tributaries that empty into it; included are the dredged cuts is about 18 feet to Hains Point. The Coan, St. Marys, Yeocomico, Wicomico and Anacostia channels are maintained at or near project depths. For Rivers. Also described are the ports of Washington, DC, detailed channel information and minimum depths as and Alexandria and several smaller ports and landings on reported by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), these waterways. use NOAA Electronic Navigational Charts. Surveys and (2) channel condition reports are available through a USACE COLREGS Demarcation Lines hydrographic survey website listed in Appendix A. (3) The lines established for Chesapeake Bay are (12) described in 33 CFR 80.510, chapter 2. Anchorages (13) Vessels bound up or down the river anchor anywhere (4) ENCs - US5VA22M, US5VA27M, US5MD41M, near the channel where the bottom is soft; vessels US5MD43M, US5MD44M, US4MD40M, US5MD40M sometimes anchor in Cornfield Harbor or St. -

2018 Coast Guard ATON Assessment

U.Ss Coast Guard’s Federal ATON Assessment of Virginia Waterways This 43-page assessment was compiled to provide a consolidated list of the status of federal ATON in Virginia Waterways. The information in this assessment will be used to assist the Coast Guard with managing the federal ATONs in Virginia’s waterways based on water depths/shoaling that are considered stable, moderate, or severe. The key below provides symbology used on these charts. Key for Charts Meaning Symbol Federal navigation project FNP Best Water BW Waterway is stable Green Waterway is shoaled in Red The waterway's entrance is Green over stable but the end is shoaled in Red The waterway's entrance is Red over shoaled in but the end is stable Green The waterway is shoaled in but Red over White there is a project ongoing 1 2 Virginia Chart A (Read Bay side North to South then Ocean Side North to South) WW Waterway (WW) Type Depth (ft) Notes Coast Guard asset cannot access all of this waterway, under Starling Creek (VA) FNP 6 review Coast Guard asset cannot access all of this waterway, under Muddy Creek (VA) BW 6 to 3 review Not less Guilford Creek (VA) BW than 6 No issues 10 to less There is shoaling at entrance of this waterway, currently under Hunting Creek (VA) BW than 5 review There is shoaling at entrance of this waterway, currently under Deep Creek (VA) FNP 8 review Chessconessex Creek There is shoaling at entrance of this waterway, currently under (VA) BW 14 to 5 review Chincoteague Inner This waterway has shoaling in multipul areas and Coast Guard Channel FNP -

Potomac Basin Large River Environmental Flow Needs

Potomac Basin Large River Environmental Flow Needs PREPARED BY James Cummins, Claire Buchanan, Carlton Haywood, Heidi Moltz, Adam Griggs The Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street Suite PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 R. Christian Jones, Richard Kraus Potomac Environmental Research and Education Center George Mason University 4400 University Drive, MS 5F2 Fairfax, VA 22030-4444 Nathaniel Hitt, Rita Villella Bumgardner U.S. Geological Survey Leetown Science Center Aquatic Ecology Branch 11649 Leetown Road, Kearneysville, WV 25430 PREPARED FOR The Nature Conservancy of Maryland and the District of Columbia 5410 Grosvenor Lane, Ste. 100 Bethesda, MD 20814 WITH FUNDING PROVIDED BY The National Park Service Final Report May 12, 2011 ICPRB Report 10-3 To receive additional copies of this report, please write Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe St., PE-08 Rockville, MD 20852 or call 301-984-1908 Disclaimer This project was made possible through support provided by the National Park Service and The Nature Conservancy, under the terms of their Cooperative Agreement H3392060004, Task Agreement J3992074001, Modifications 002 and 003. The content and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the policy of the National Park Service or The Nature Conservancy and no official endorsement should be inferred. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed as representing the opinions or policies of the U. S. Government, or the signatories or Commissioners to the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin. Acknowledgments This project was supported by a National Park Service subaward provided by The Nature Conservancy Maryland/DC Office and by the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin, an interstate compact river basin commission of the United States Government and the compact's signatories: Maryland, Virginia, Pennsylvania, West Virginia and the District of Columbia. -

Shoreline Erosion in Tidewater Virginia

W&M ScholarWorks Reports 1-1-1976 Shoreline Erosion in Tidewater Virginia Robert J. Byrne Virginia Institute of Marine Science Gary L. Anderson Virginia Institute of Marine Science Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/reports Part of the Marine Biology Commons Recommended Citation Byrne, R. J., & Anderson, G. L. (1976) Shoreline Erosion in Tidewater Virginia. Special Reports in Applied Marine Science and Ocean Engineering (SRAMSOE) No. 111, Chesapeake Research Consortium Report No. 8. Virginia Institute of Marine Science, William & Mary. https://doi.org/10.21220/V5H74Z This Report is brought to you for free and open access by W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reports by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHORELINE EROSION IN TIDEWATER VIRGINIA Supported by the National Science Foundation, Research Applied to National Needs Program NSF Grant Nos. GI 29909 and 34869 to the Chesapeake Research Consortium, Inc. Chesapeake Research Consortium Report Number 8 Special Report in Applied Marine Science and Ocean Engineering Number 111 of the VIRGINIA INSTITUTE OF MARINE SCIENCE Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062 SHORELINE EROSION IN TIDEWATER VIRGINIA PREPARED BY: ROBERT J. BYRNE GARY L. ANDERSON Supported by the National Science Foundation, Research Applied to National Needs Program NSF Grant Nos. GI 29909 and 34869 to the Chesapeake Research Consortium, Inc. Chesapeake Research Consortium Report Number 8 Special Report in Applied Marine Science and Ocean Engineering Number 111 of the VIRGINIA INSTITUTE OF MARINE SCIENCE William J. Hargis, Jr., Director Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES PAGE PAGE PART I: THE SHORELINE EROSION STUDY l FIGURE 1: Schematic Representation of Parameters 3 FIGURE 2: Subsystems Within the Chesapeake Bay System 4 A.