202B Targeting Resources Report.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biodiversity Work Group Report: Appendices

Biodiversity Work Group Report: Appendices A: Initial List of Important Sites..................................................................................................... 2 B: An Annotated List of the Mammals of Albemarle County........................................................ 5 C: Birds ......................................................................................................................................... 18 An Annotated List of the Birds of Albemarle County.............................................................. 18 Bird Species Status Tables and Charts...................................................................................... 28 Species of Concern in Albemarle County............................................................................ 28 Trends in Observations of Species of Concern..................................................................... 30 D. Fish of Albemarle County........................................................................................................ 37 E. An Annotated Checklist of the Amphibians of Albemarle County.......................................... 41 F. An Annotated Checklist of the Reptiles of Albemarle County, Virginia................................. 45 G. Invertebrate Lists...................................................................................................................... 51 H. Flora of Albemarle County ...................................................................................................... 69 I. Rare -

Title 26 Department of the Environment, Subtitle 08 Water

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION Chapters 01-10 2 26.08.01.00 Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION Chapter 01 General Authority: Environment Article, §§9-313—9-316, 9-319, 9-320, 9-325, 9-327, and 9-328, Annotated Code of Maryland 3 26.08.01.01 .01 Definitions. A. General. (1) The following definitions describe the meaning of terms used in the water quality and water pollution control regulations of the Department of the Environment (COMAR 26.08.01—26.08.04). (2) The terms "discharge", "discharge permit", "disposal system", "effluent limitation", "industrial user", "national pollutant discharge elimination system", "person", "pollutant", "pollution", "publicly owned treatment works", and "waters of this State" are defined in the Environment Article, §§1-101, 9-101, and 9-301, Annotated Code of Maryland. The definitions for these terms are provided below as a convenience, but persons affected by the Department's water quality and water pollution control regulations should be aware that these definitions are subject to amendment by the General Assembly. B. Terms Defined. (1) "Acute toxicity" means the capacity or potential of a substance to cause the onset of deleterious effects in living organisms over a short-term exposure as determined by the Department. -

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5 DATABASE DESIGN DOCUMENTATION AND DATA DICTIONARY 1 June 2013 Prepared for: United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, Maryland 21403 Prepared By: Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 Prepared for United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, MD 21403 By Jacqueline Johnson Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin To receive additional copies of the report please call or write: The Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 301-984-1908 Funds to support the document The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.0; Database Design Documentation And Data Dictionary was supported by the US Environmental Protection Agency Grant CB- CBxxxxxxxxxx-x Disclaimer The opinion expressed are those of the authors and should not be construed as representing the U.S. Government, the US Environmental Protection Agency, the several states or the signatories or Commissioners to the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin: Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia or the District of Columbia. ii The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.5 TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. -

Morgan County Relocation Package

Morgan County Relocation Package Long & Foster/Webber & Associates, Realtors® 480 W. Jubal Early Drive, Suite 100 Winchester, Virginia 22601 Office: 540-662-3484 - Toll Free: 800-468-6619 www.webberrealty.com TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------2 GOVERNMENT -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------3 TAXES ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------4-5 LICENSE ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------5-6 IMPORTANT NUMBERS -----------------------------------------------------------------------7 HEALTH ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------8-9 CLIMATE ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------10 POPULATION --------------------------------------------------------------------------------10-11 CHURCHES ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------12 TEMPORARY LODGING -----------------------------------------------------------------12-14 SHOPPING ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------15 TRANSPORTATION ---------------------------------------------------------------------------16 SCHOOLS -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------17-18 LIBRARIES ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------19 -

Maryland's 2016 Triennial Review of Water Quality Standards

Maryland’s 2016 Triennial Review of Water Quality Standards EPA Approval Date: July 11, 2018 Table of Contents Overview of the 2016 Triennial Review of Water Quality Standards ............................................ 3 Nationally Recommended Water Quality Criteria Considered with Maryland’s 2016 Triennial Review ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Re-evaluation of Maryland’s Restoration Variances ...................................................................... 5 Other Future Water Quality Standards Work ................................................................................. 6 Water Quality Standards Amendments ........................................................................................... 8 Designated Uses ........................................................................................................................... 8 Criteria ....................................................................................................................................... 19 Antidegradation.......................................................................................................................... 24 2 Overview of the 2016 Triennial Review of Water Quality Standards The Clean Water Act (CWA) requires that States review their water quality standards every three years (Triennial Review) and revise the standards as necessary. A water quality standard consists of three separate but related -

2014 Virginia Freshwater Fishing & Watercraft Owner’S Guide

2014 Virginia Freshwater Fishing & Watercraft Owner’s Guide Free Fishing Days: June 6–8, 2014 National Safe Boating Week: May 17–23, 2014 www.HuntFishVA.com Table of Contents Freshwater Fishing What’s New For 2014................................................5 Fishing License Information and Fees ....................................5 Commonwealth of Virginia Freshwater/Saltwater License Lines on Tidal Waters .........................8 Terry McAuliffe, Governor Reciprocal Licenses .................................................8 General Freshwater Fishing Regulations ..................................9 Department of Game Game/Sport Fish Regulations.........................................11 Creel and Length Limit Tables .......................................12 and Inland Fisheries Trout Fishing Guide ................................................18 Bob Duncan, Executive Director 2014 Catchable Trout Stocking Plan...................................20 Members of the Board Special Regulation Trout Waters .....................................22 Curtis D. Colgate, Chairman, Virginia Beach Fish Consumption Advisories .........................................26 Ben Davenport, Vice-Chairman, Chatham Nongame Fish, Reptile, Amphibian, and Aquatic Invertebrate Regulations........27 David Bernhardt, Arlington Let’s Go Fishing Lisa Caruso, Church Road Fish Identification and Fishing Information ...............................29 Charles H. Cunningham, Fairfax Public Lakes Guide .................................................37 Garry L. Gray, -

Maryland Stream Waders 10 Year Report

MARYLAND STREAM WADERS TEN YEAR (2000-2009) REPORT October 2012 Maryland Stream Waders Ten Year (2000-2009) Report Prepared for: Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 1-877-620-8DNR (x8623) [email protected] Prepared by: Daniel Boward1 Sara Weglein1 Erik W. Leppo2 1 Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 2 Tetra Tech, Inc. Center for Ecological Studies 400 Red Brook Boulevard, Suite 200 Owings Mills, Maryland 21117 October 2012 This page intentionally blank. Foreword This document reports on the firstt en years (2000-2009) of sampling and results for the Maryland Stream Waders (MSW) statewide volunteer stream monitoring program managed by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources’ (DNR) Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division (MANTA). Stream Waders data are intended to supplementt hose collected for the Maryland Biological Stream Survey (MBSS) by DNR and University of Maryland biologists. This report provides an overview oft he Program and summarizes results from the firstt en years of sampling. Acknowledgments We wish to acknowledge, first and foremost, the dedicated volunteers who collected data for this report (Appendix A): Thanks also to the following individuals for helping to make the Program a success. • The DNR Benthic Macroinvertebrate Lab staffof Neal Dziepak, Ellen Friedman, and Kerry Tebbs, for their countless hours in -

Annual and Seasonal Trends in Discharge of National Capital Region Streams

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Annual and Seasonal Trends in Discharge of National Capital Region Streams Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCRN/NRTR—2011/488 ON THE COVER Potomac River near Paw Paw, West Virginia Photograph by: Tom Paradis, NPS. Annual and Seasonal Trends in Discharge of National Capital Region Streams Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCRN/NRTR—2011/488 John Paul Schmit National Park Service Center for Urban Ecology 4598 MacArthur Blvd. NW Washington, DC 20007 September, 2011 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Technical Report Series is used to disseminate results of scientific studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series provides contributors with a forum for displaying comprehensive data that are often deleted from journals because of page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. This report received formal peer review by subject-matter experts who were not directly involved in the collection, analysis, or reporting of the data, and whose background and expertise put them on par technically and scientifically with the authors of the information. -

Springs, Source Water Areas, and Potential for High-Yield Aquifers Along the Cacapon Mountain Anticline, Morgan County, WV

Springs, source water areas, and potential for high-yield aquifers along the Cacapon Mountain anticline, Morgan County, WV Joseph J. Donovan Eberhard Werner Dorothy J. Vesper Lacoa Corder Hydrogeology Research Center West Virginia Water Research Institute West Viriginia University Final Report, Project HRC-3 May 2006 Abstract An investigation was made of high-yield water resources of Morgan County, focusing specifically on the Helderberg-Tonoloway-Wills Creek limestone units. These plus the associated underlying Silurian clastic rocks are thought to constitute a groundwater flow system, here referred to as the Cacapon Mountain aquifer. It lies between sandstone aquitards of the Tuscarora and Oriskany formations and flanks both sides of the Cacapon Mountain Anticline. The purpose of the investigation is to characterize the eastern side of this potential high-yield aquifer and identify its hydrogeological elements that may be critical to its development. Objectives include physical and chemical inventory/characterization of springs >10 gpm; identification of aquifer boundaries; hydrogeological mapping; chemical sampling of selected springs; and flow/chemical monitoring of 3 groundwater discharges in different portions of the aquifer. Results include location of wells in and springs discharging from the aquifer in Cold Run Valley. The aquifer may be subdivided into four compartments of groundwater movement based on inferred directions of groundwater flow. The largest of these is the Sir Johns Run catchment, which collects groundwater discharge at a nearly linear rate and discharges to the Potomac. The other three compartments discharge to tributaries of Sleepy Creek via water gaps in Warm Springs Ridge. During measurements in fall 2004, discharge via Sir Johns Run near its mouth was 6.75 cfs, suggesting that aquifer-wide, in excess of 10 cfs may be available throughout the study area for additional development. -

Floristic Discoveries in Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia

Knapp, W.M., R.F.C. Naczi, W.D. Longbottom, C.A. Davis, W.A. McAvoy, C.T. Frye, J.W. Harrison, and P. Stango, III. 2011. Floristic discoveries in Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia. Phytoneuron 2011-64: 1–26. Published 15 December 2011. ISSN 2153 733X FLORISTIC DISCOVERIES IN DELAWARE, MARYLAND, AND VIRGINIA WESLEY M. KNAPP 1 Maryland Department of Natural Resources Wildlife and Heritage Service Wye Mills, Maryland 21679 [email protected] ROBERT F. C. NACZI The New York Botanical Garden Bronx, New York 10458-5126 WAYNE D. LONGBOTTOM P.O. Box 634 Preston, Maryland 21655 CHARLES A. DAVIS 1510 Bellona Ave. Lutherville, Maryland 21093 WILLIAM A. MCAVOY Delaware Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program 4876 Hay Point, Landing Rd. Smyrna, Delaware 19977 CHRISTOPHER T. FRYE Maryland Department of Natural Resources Wildlife and Heritage Service Wye Mills, Maryland 21679 JASON W. HARRISON Maryland Department of Natural Resources Wildlife and Heritage Service Wye Mills, Maryland 21679 PETER STANGO III Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Wildlife and Heritage Service, Annapolis, Maryland 21401 1 Author for correspondence ABSTRACT Over the past decade studies in the field and herbaria have yielded significant advancements in the knowledge of the floras of Delaware, Maryland, and the Eastern Shore of Virginia. We here discuss fifty-two species newly discovered or rediscovered or whose range or nativity is clarified. Eighteen are additions to the flora of Delaware ( Carex lucorum var. lucorum, Carex oklahomensis, Cyperus difformis, Cyperus flavicomus, Elymus macgregorii, Glossostigma cleistanthum, Houstonia pusilla, Juncus validus var. validus, Lotus tenuis, Melothria pendula var. pendula, Parapholis incurva, Phyllanthus caroliniensis subsp. -

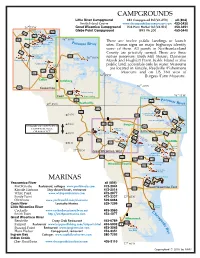

3-Fold Map.Cs2

CAMPGROUNDS Little River Campground 382 Campground Rd (VA 650) all (804) Smith Island Cruise www.chesapeakebaycampresort.com 453-3430 76o 35’W Great Wicomico Campground 836 Horn Harbor Rd (VA 810) 453-3351 White Point Glebe Point Campground 1895 VA 200 604 Marina 610 453-3440 Sandy Point 607 744 Marina Kinsale 608 76o 30’W 202 Yeocomico There are twelve public landings or launch River P 203 Port Kinsale otomac River Kinsale Harbor sites. Brown signs on major highways identify Marina some of them. All ponds in Northumberland 617 County are privately owned. There are three Hampton Hall Landing 624 o (being developed) Lewisetta 38 00’N nature preserves: Bush Mill Stream, Dameron Gardys Millpond Marina Marsh and Hughlett Point. Kohls Island is also Lodge Landing The Glebe Olversons public land, accessible only by water. Museums Marina are located in Kinsale, Reedville (Fishermens 712 623 Cod Creek 202 Coan River Museum) and on US 360 west of 76o 25’W 360 Burgess (Farm Museum). Callao Lottsburg Presley Creek 76o 20’W 360 Yeocomico Forrest Landing Hull Creek 612 Cubitt Creek Hacks Creek o Coan Rowes Landing 76 15’W Vir-Mar Beach 601 643 Potoma o c 37 55’N Heathsville River 360 648 201 Cockrells Railway 644 54’N 644 & Marina Kohls Island Ferry Little Wicomico River 650 Little River campground 53’N 707 639 Burgess 1 degree of latitude Smith Point = 360 651Marina 1 nautical mile, Cedar Point Landing 644 or 6080 feet 699 Little Wicomico 52’N Coopers Landing campgroundGlebe Point 652 Bush Mill Stream Great Wicomico 663 Sampsons Wharf campground -

Northern Neck of Virginia Historical Magazine

§aA,SE’8433/1'7 47‘.1Ta. 59- 1199772» M0Y‘i'” '\& ~ C; N 1311 N k t . y . ‘Q . § of V1rgm1a Q ’ Historical “ . ‘I 0 5 I\. Ma gaz1nc <~ ’ l ( ‘ DECEMBER,1960 .\. ‘I’ ‘x’ . 3, VOL. X No. 1 5 .\I. ii ‘i '\ Reportof the ActingPresident 863 «; The Cavalier. ThomaxLomaxHunter 865 ' _ “Virginiana” for Posterity. Ross Valentine 867 _ ’ § The Old Pope’s Creek Church Site. Treadwell Davixon ........................................................869 i ' ‘\’ Captain John Haynie 872 4 ‘ ‘ / The Lost Settlement of Queenstown. iames Wharton ...............................................................875 \ _ &, ' OldExeter Famham LodgeAmong Plantation. Most 7ames Interesting Motley Virginia Booker, Shrines. M.D .............................................................883 Addie V. Payne...............880 . ' _ .\; Northern Neck Epitaphs. Miriam Haynie 899 .1, - I A Reminder to the Historical Society 901 ‘ & Memorialto Robert Opie Norris,Jr 903 § ' \ A History of Menhaden Industry in Virginia 910 1 I ‘} Miscellaneous Legislative Petitions 925 ‘\' . Q_ ' EleventhGaskinsMemorialTablet Annual Meeting 94.5939 ‘.§ . (\, Membership List 948 {, / In Memoriam 958 \ ' ; Published Annually by g, ‘ -{ THE NORTHERN NECK ofVIRGINIA ‘, " - HISTORICAL SOCIETY A MONTROSS, Westmoreland County, VIRGINIA 4<» - {, Sacramenlo Brandi fienealogical Library NORTHERN NECK OF VIRGINIA HISTORICAL SOCIETY MONTROSS. WESTMOREIAND COUNTY, VIRGINIA '8? Officers SENATOR R. O. NORRIS, JR., Lively, Virginia President Mu. Tnoiuis L. Human, King George,Virginia Secretary Miss Lucy BRowNBun, Hague, Virginia Histarian F. F. CHANDLER,Montross, Virginia Treasurer Mas. F. F. CHANDILR,Montross, Virginia ‘ Executive Assistant C. F. UNRu1-1 MRS. LOUISE S'I'auAR'r BJORNSSON BEVERLEYBRouN Kinsale, Virginia State of Colorado State of West Virginia Mas. E. Huoi-I Surm A. MAXCoi>rAoIs MR5. Jusns MAcMuLi.aN Heathsville, Virginia State of Missouri State of New Jersey MR3.