'Nameless Motif'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

Botanical Composition and Species Diversity of Arid and Desert Rangelands in Tataouine, Tunisia

land Article Botanical Composition and Species Diversity of Arid and Desert Rangelands in Tataouine, Tunisia Mouldi Gamoun and Mounir Louhaichi * International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), 2049 Ariana, Tunisia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +216-7175-2099 Abstract: Natural rangelands occupy about 5.5 million hectares of Tunisia’s landmass, and 38% of this area is in Tataouine governorate. Although efforts towards natural restoration are increasing rapidly as a result of restoration projects, the area of degraded rangelands has continued to expand and the severity of desertification has continued to intensify. Any damage caused by disturbances, such as grazing and recurrent drought, may be masked by a return of favorable rainfall conditions. In this work, conducted during March 2018, we surveyed the botanical composition and species diversity of natural rangelands in Tataouine in southern Tunisia. The flora comprised about 279 species belonging to 58 families, with 54% annuals and 46% perennials. The Asteraceae family had the greatest richness of species, followed by Poaceae, Fabaceae, Amaranthaceae, Brassicaceae, Boraginaceae, Caryophyllaceae, Lamiaceae, Apiaceae, and Cistaceae. Therophytes made the highest contribution, followed by chamaephytes and hemicryptophytes. Of all these species, 40% were palatable to highly palatable and more than 13% are used in both traditional and modern medicine. Citation: Gamoun, M.; Louhaichi, M. Keywords: vegetation; species richness; drylands; south of Tunisia Botanical Composition and Species Diversity of Arid and Desert Rangelands in Tataouine, Tunisia. Land 2021, 10, 313. https://doi.org/ 1. Introduction 10.3390/land10030313 Climate change and human activity represent a big threat to biodiversity [1–3]. -

NDI Tunisia Focus Group Report

DEMANDING TANGIBLE ACHIEVEMENTS: TUNISIAN CITIZENS EXPRESS THEIR VIEWS ON THE PARLIAMENT, THE RECENT MUNICIPAL ELECTIONS AND UPCOMING ELECTIONS FINDINGS FROM FOCUS GROUPS IN TUNISIA Conducted September 26 to October 3, 2018 By: Rick Nadeau, and, Assil Kedissi, NDI November 2018 National Democratic Institute The National Democratic Institute for International Affairs (NDI) is a nonprofit, nonpartisan, nongovernmental organization that responds to the aspirations of people around the world to live in democratic societies that recognize and promote basic human rights. Since its founding in 1983, NDI and its local partners have worked to support and strengthen political and civic organizations, safeguard elections, and promote citizen participation, openness and accountability in government. With staff members and volunteer political practitioners from more than 96 nations, NDI brings together individuals and groups to share ideas, knowledge, experiences and expertise. Partners receive broad exposure to best practices in international democratic development that can be adapted to the needs of their own countries. NDI’s approach reinforces the message that while there is no single democratic model, certain core principles are shared by all democracies. The Institute’s work upholds the principles enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It also promotes the development of institutionalized channels of communications among citizens, political institutions and elected officials, and strengthens their ability to improve the quality of life for all citizens. For more information about NDI, please visit www.ndi.org. Washington, DC 455 Massachusetts Ave, NW, 8th Floor Washington, DC 20001-2621 Telephone: (+1) 202-728-5500 Fax: (+1) 202-728-5520 Website: www.ndi.org Tunis, Tunisia Email: [email protected] Telephone: (+216) 71-844-264 This report is made possible through funding from the Middle East Partnership Initiative (MEPI) under award No. -

Disseminating Design: the Post-War Regional Impact of the Victoria & Albert Museum’S Circulation Department

DISSEMINATING DESIGN: THE POST-WAR REGIONAL IMPACT OF THE VICTORIA & ALBERT MUSEUM’S CIRCULATION DEPARTMENT JOANNA STACEY WEDDELL A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Brighton in collaboration with the Victoria & Albert Museum for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2018 BLANK 2 Disseminating Design: The Post-war Regional Impact of the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Circulation Department This material is unavailable due to copyright restrictions. Figure 1: Bill Lee and Arthur Blackburn, Circulation Department Manual Attendants, possibly late 1950s, MA/15/37, No. V143, V&A Archive, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Joanna Weddell University of Brighton with the Victoria and Albert Museum AHRC Part-time Collaborative Doctoral Award AH/I021450/1 3 BLANK 4 Thesis Abstract This thesis establishes the post-war regional impact of the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Circulation Department (Circ) which sent touring exhibitions to museums and art schools around the UK in the period 1947-1977, an area previously unexplored to any substantial depth. A simplistic stereotypical dyad of metropolitan authority and provincial deference is examined and evidence given for a more complex flow between Museum and regions. The Introduction outlines the thesis aims and the Department’s role in the dissemination of art and design. The thesis is structured around questions examining the historical significance of Circ, the display and installation of Circ’s regional exhibitions, and the flow of influence between regions and museum. Context establishes Circ not as a straightforward continuation of Cole’s Victorian mission but as historically embedded in the post-war period. -

THE ARMENIAN CULTURAL FOUNDATION Ticipating in Unveiling a Commemorative Plaque Rooms

NOVEMBER 2, 2013 MirTHErARoMENr IAN -Spe ctator Volume LXXXIV, NO. 16, Issue 4310 $ 2.00 NEWS IN BRIEF The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Since 1932 School No. 44 in Nishan Atinizian Yerevan Named for Receives Anania Armenian ‘Orphan Rug’ Is in White House Hrant Dink Shiragatsi Medal from Storage, as Unseen as Genocide Is Neglected YEREVAN (Armenpress) — Mayor of Yerevan Taron Margaryan attended the solemn ceremony WASHINGTON (Washington Post) — The of naming the capital’s school No. 44 after President of Armenia rug was woven by orphans in the 1920s and By Philip Kennicott prominent Armenian journalist and intellectual formally presented to the White House in YEREVAN — Every year, during from Istanbul Hrant Dink this week. The 1925. A photograph shows President Calvin Armenia’s independence celebrations, the Information and Public Relations Department of Coolidge standing on the carpet, which is no mere juvenile effort, but a president of the republic hands out awards the Yerevan Municipality reported that aside complicated, richly detailed work that would hold its own even in the largest to individuals in Armenia and the diaspora from the mayor, Dink’s widow Rackel Dink, par - and most ceremonial who are outstanding in their fields and PHOTO COURTESY OF THE ARMENIAN CULTURAL FOUNDATION ticipating in unveiling a commemorative plaque rooms. have contributed to the betterment of dedicated to Hrant Dink. If you can read a Armenia. Hrant Dink was assassinated in Istanbul in carpet’s cues, the This year, among the honorees singled January 2007, by Ogün Samast, a 17-year old plants and animals out by President Serge Sargisian was Turkish nationalist. -

Textile Society of America Newsletter 28:1 — Spring 2016 Textile Society of America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Newsletters Textile Society of America Spring 2016 Textile Society of America Newsletter 28:1 — Spring 2016 Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews Part of the Art and Design Commons Textile Society of America, "Textile Society of America Newsletter 28:1 — Spring 2016" (2016). Textile Society of America Newsletters. 73. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews/73 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Newsletters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME 28. NUMBER 1. SPRING, 2016 TSA Board Member and Newsletter Editor Wendy Weiss behind the scenes at the UCB Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver, durring the TSA Board meeting in March, 2016 Spring 2016 1 Newsletter Team BOARD OF DIRECTORS Roxane Shaughnessy Editor-in-Chief: Wendy Weiss (TSA Board Member/Director of External Relations) President Designer and Editor: Tali Weinberg (Executive Director) [email protected] Member News Editor: Caroline Charuk (Membership & Communications Coordinator) International Report: Dominique Cardon (International Advisor to the Board) Vita Plume Vice President/President Elect Editorial Assistance: Roxane Shaughnessy (TSA President) [email protected] Elena Phipps Our Mission Past President [email protected] The Textile Society of America is a 501(c)3 nonprofit that provides an international forum for the exchange and dissemination of textile knowledge from artistic, cultural, economic, historic, Maleyne Syracuse political, social, and technical perspectives. -

Soils of Tunisia

Soils of Tunisia Amor Mtimet1 Introduction Pedological studies based on soil survey, photo- interpretation, laboratory analysis, and remote sensing, were implemented in Tunisia since more than half-century. The magnitude of these surveys is so high that they practically cover the whole territory of the country. They were aimed mainly at acquiring better knowledge of country’s soil re- sources in order to use them in land reclamation and agricultural development projects. Therefore, Tunisia is among the few African countries where abundant soil data and studies are available. They include: • 636 Pedological studies; • 310 Specialised pedological studies; • 2,085 Preliminary survey studies; and • 18 Bulletins published by the Soils Directorate. Thus totalling 3,049 classified documents. About 65% of the total surface area of the country is covered by pedological surveys, which equals to about 10,669,000 ha. Nevertheless some of those concerned with agriculture development, often ig- nore this large mass of valuable soil data. It is becoming evident that the decision-makers are more prone to consider crop and animal production, hy- draulic works and management plans rather than the sustainable use of land resources. In order to benefit from the funds of a new agri- culture policy, the use of soil information has be- come a must, and those who are in charge of the na- tional development should start addressing also the 1 Direction des Sols, Ministry of Agriculture, Tunis, Tunisia. 243 Options Méditerranéennes, Série B, n. 34 Soils of Tunisia sustainable management of soil services. Extension services to farmers are now evolving which would allow them to an easier access to soil information. -

The Armenian Govern - Christian Roots, the Left-To-Right Direction - Karabagh Region

OCTOBER 18, 2014 MirTHErARoMENr IAN -Spe ctator Volume LXXXV, NO. 14, Issue 4357 $ 2.00 NEWS IN BRIEF The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Since 1932 Baku Furious Over Armenia’s Eurasian Accession: Security Guarantee the Game Changer French Karabagh Visit to turn down a potential association agree - point to long historical associations with BAKU (RFE/RL) — Azerbaijan is irate over a By Pietro A. Shakarian ment with the European Union (EU). Europe. These include their shared French mayor’s visit to the breakaway Nagorno- The decision by the Armenian govern - Christian roots, the left-to-right direction - Karabagh region. ment has sparked debate in Armenian ality of the Armenian alphabet, contacts The Foreign Ministry in Baku said the October YEREVAN (Hetq) — On October 10, society about the respective benefits of between the old Armenian kingdoms and 4-6 visit by the mayor of the French town of Armenia officially joined the Eurasian the two rival blocs. It is true that the West, and even the very personality of Bourg-les-Valence, Marlene Mourier, was a Customs Union. It was more than a year Armenians have long sought to integrate Charles Aznavour. In fact, to an Armenian “provocation” ahead of a meeting between the ago that the country made its fateful deci - their country with Europe and, like their or Georgian, the idea of possibly joining presidents of Azerbaijan and Armenia in Paris sion to join the Moscow-backed union and northern neighbors the Georgians, they see EURASIA, page 2 later this month. The ministry’s -

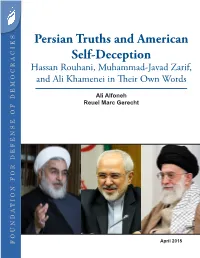

Persian Truths and American Self-Deception Hassan Rouhani, Muhammad-Javad Zarif, and Ali Khamenei in Their Own Words

Persian Truths and American Self-Deception Hassan Rouhani, Muhammad-Javad Zarif, and Ali Khamenei in Their Own Words Ali Alfoneh Reuel Marc Gerecht April 2015 FOUNDATION FOR DEFENSE OF DEMOCRACIES FOUNDATION Persian Truths and American Self-Deception Hassan Rouhani, Muhammad-Javad Zarif, and Ali Khamenei in Their Own Words Ali Alfoneh Reuel Marc Gerecht April 2015 FDD PRESS A division of the FOUNDATION FOR DEFENSE OF DEMOCRACIES Washington, DC Persian Truths and American Self-Deception Table of Contents Introduction: A Decent Respect for the Written Word [in Persian] ......................................................................... 2 I: The Man and The Myth: The Many Faces of Hassan Rouhani ............................................................................. 4 II: An Iranian Moderate Exposed: Everyone Thought Iran’s Foreign Minister Was a Pragmatist. They Were Wrong. .............................................................................................................................................................................. 19 III: Iran’s Supreme Censor: The Evolution of Ali Khamenei from Sensitive Lover of Western Literature to Enforcer of Islamic Revolutionary Orthodoxy .......................................................................................................... 25 Persian Truths and American Self-Deception Introduction: A Decent Respect ever-so-short reform movement under president Mohammad Khatami) — they may have read little for the Written Word [in Persian] of the writings of the mullahs -

Weaving Books and Monographs

Tuesday, September 10, 2002 Page: 1 ---. 10 Mujeres y Textil en 3d/10 Women and Textile Into 3. [Mexico City, Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico. Galeria Aristos, 1975], 1975. ---. 10 Mujeres y Textil en 3d/10 Women and Textile Into 3. [Mexico City, Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico. Galeria Aristos, 1975], 1975. ---. 100 Jahre J. Hecking; Buntspinnerei und Weberei. Wiesbaden, Verlag f?r Wirtschaftspublizistik Bartels, 1958. ---. 100 Years of Native American Arts: Six Washington Cultures. [Tacoma, Washington: Tacoma Art Museum, 1988], 1988. ---. 1000 [i.e. Mil] Años de Tejido en la Argentina: [Exposici?n] 24 de Mayo Al 18 Junio de 1978. Buenos Aires: Ministerio de Cultura y Educaci?n, Secretaría de Cultura, Instituto Nacional de Antropología, 1978. ---. 1000 Years of Art in Poland. [London, Great Britain: Royal Academy of Arts, 1970], 1970. ---. 101 Ways to Weave Better Cloth: Selected Articles of Proven Interest to Weavers Chosen from the Pages of Textile Industries. Atlanta, GA.: Textile Indistries, 1960. ---. 125 Jahre Mech. Baumwoll-Spinnerei und Weberei, Augsburg. [Augsburg, 1962. ---. 1977 HGA Education Directory. West Hartford, CT: Handweavers Guild of America, 1978. ---. 1982 Census of Manufactures. Preliminary Report Industry Series. Weaving Mills. [Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of, 1984. ---. 1987 Census of Manufactures. Industry Series. Weaving and Floor Covering Mills, Industries 2211, 2221, 2231, 2241, and 2273. Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of, 1990. ---. 1987 Census of Manufactures. Preliminary Report. Industry Series. Weaving and Floor Covering Mills: Industries 2211, 2221, 2241, and 2273. [Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of, 1994. ---. 1992 Census of Manufactures. -

Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 9-2012 Textile Society of America- Abstracts and Biographies Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf "Textile Society of America- Abstracts and Biographies" (2012). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 761. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/761 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The Changing Politics of Textiles as Portrayed on Somali Postage Stamps Heather Akou When Somalia became an independent nation in 1960, the change in power was celebrated with new postage stamps. Departing from the royal portraits and vague images of "natives" favored by their colonizers, Somalis chose to circulate detailed images of local plants, animals, artisanal products, and beautiful young women in wrapped fabrics. In the early 1960s, these images were fairly accurate representations of contemporary fashions. Over the next twenty years, with a few notable exceptions, these images became more romanticized focusing on the folk dress worn by nomads in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Confronting drought, corruption, and economic interference from the West, dictator Siad Barre (who came to power in a military coup in 1969) longed openly for the "good old days" of nomadic life. As the country became increasingly unstable in the 1980s, leading to the collapse of the national government in 1991, postal depictions of textiles and wrapped clothing became even more divorced from reality: surface patterns unrelated to the drape of the cloth, fabrics that were too thin or wrapped in impossible ways, and styles of dress that were nothing but fantasy. -

Id Title Publisher Year Subtitle Dep Isbn1 Isbn2

ID TITLE PUBLISHER YEAR SUBTITLE DEP ISBN1 ISBN2 BOOK NR AUTHOR 1 The women's warpath ucla fowler museum of 1996 Iban ritual fabrics from borneo 15 0-930741-50-1 0-930741-51-x SEA0001 Traude Gavin cultural history 2 Textile traditions of Los Angeles county 1977 15 0-87587-083-x SEA0002 Mary Hunt Kahlenberg Indonesia museum of art 3 Indonesische Textilien Deutsches Textilmuseum 1984 Wege zu Göttern und Ahnen 15 3-923158-05-X SEA0003 Brigitte Khan Majlis Krefeld 4 Walk in splendor ucla fowler museum of 1999 ceremonial dress and the 15 0-930741-72-2 0-930741-73-0 SEA0004 T.Abdullah cultural history Minangkabau 5 Geometrie d'Oriente sillabe, Livorno 1999 Stefano Bardini e il tappeto 5 88 -8347- 010-9 GEN0029 Alberto Boralevi Oriental Geometries antico Stefano Bardini and the Antique Carpet 6 Her-ontdekking van Lamandart 1994 17 90-5276-009-8 90-5276-008-X SNA0001 Brommer,De Precolumbiaans Textiel Bolle,Hughes,Pollet,Sorbe r,Verhecken 7 Eeuwen van weven Nederlands 1992 Bij de Hopi- en Navajo- indianen 17 90-7096217-9 SNA0002 Helena Gelijns, Fred van Textielmuseum Tilburg Oss 8 Bolivian Indian Textiles dover publications, inc. 1981 Traditional Designs and 17 0-486-24118-1 SNA0003 Tamara E.Wasserman, Costumes Jonathan S.Hill 9 3000 jaar weven in de Andes Gemeentemuseum 1988 textiel uit Peru en Bolivia 17 90 68322 14 1 SNA0004 Brommer, Lugtigheid, Helmond Roelofs, Mook-Andreae 10 Coptic Textiles The friends of the Benaki 1971 22 Mag0019 Benaki Museum Museum,Athens 11 Coptic Fabrics Adam Biro 1990 14 2-87660-084-6 CPC0002 Marie Helene Rutschowscaya