Factional Politics in Orissa Since 1975

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

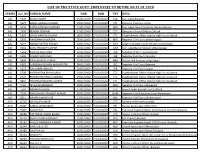

List of the State Govt. Employees to Retire on 31.01.2020

LIST OF THE STATE GOVT. EMPLOYEES TO RETIRE ON 31.01.2020 SERIES A/C_NO SUBSCR_NAME DOB DOR TRY DESG AJO 5045 MALLIK NIKRA 15/01/1960 31/01/2020 PLB Civil Judge,Baliguda AJO 5227 BARAL BAIRAGI CHARAN 18/01/1960 31/01/2020 PRI Registrar Civil Courts,Puri AJO 5233 PATRA KAISASH CHANDRA 17/01/1960 31/01/2020 KRD Civil Judge (Senior Division), Banpur,Banpur AJO 5330 BEHERA DEBARAJ 17/01/1960 31/01/2020 CTC Advocate General Odisha,Cuttack AJO 5369 SINGH RAMESH KUMAR 08/01/1960 31/01/2020 CTC Establishment Officer Odisha High Court,Cuttack AJO 5393 PANIGRAHI RAJENDRA 03/01/1960 31/01/2020 NRG Registrar Civil Courts,Nabarangpur AJO 5491 NAYAK PABITRA KUMAR 03/01/1960 31/01/2020 KHD Judge in Charge Civil & Session Court,Khurda AJO 5532 SAHU PRASANT KUMAR 22/01/1960 31/01/2020 GJM Civil Judge(Senior Division),Bhanjanagar AJO 5568 MISHRA RAJENDRA 02/01/1960 31/01/2020 BLG Registrar of Civil Court,Bolangir AJO 5586 SAHOO NARAYANA 30/01/1960 31/01/2020 KJR Registrar Civil Court,Keonjhar AJO 5894 DASH KHIROD KUMAR 01/02/1960 31/01/2020 ANG District and Sessions Judge,Angul AJO 6067 SANGRAM KESHARI MOHAPATRA 08/01/1960 31/01/2020 BLS Registrar Civil Court,Balasore AJO 6157 DAS JANAKI BALLAV 01/02/1960 31/01/2020 JPR Registrar Civil Courts,Jajpur AJO 6708 MOHAPATRA BRUNDABAN 29/01/1960 31/01/2020 CTC Establishment Officer Odisha High Court,Cuttack AJO 6722 BOHIRA KRUSHNA CHANDRA 09/01/1960 31/01/2020 CTC Establishment Officer Odisha High Court,Cuttack AJO 6892 PRADHAN BASANTA KUMAR 18/01/1960 31/01/2020 CTC Establishment Officer Odisha High Court,Cuttack -

View Entire Book

ORISSA REVIEW VOL. LXI NO. 12 JULY 2005 DIGAMBAR MOHANTY, I.A.S. Commissioner-cum-Secretary BAISHNAB PRASAD MOHANTY Director-cum-Joint Secretary SASANKA SEKHAR PANDA Joint Director-cum-Deputy Secretary Editor BIBEKANANDA BISWAL Associate Editor Sadhana Mishra Editorial Assistance Manas R. Nayak Cover Design & Illustration Hemanta Kumar Sahoo Manoj Kumar Patro D.T.P. & Design The Orissa Review aims at disseminating knowledge and information concerning Orissa’s socio-economic development, art and culture. Views, records, statistics and information published in the Orissa Review are not necessarily those of the Government of Orissa. Published by Information & Public Relations Department, Government of Orissa, Bhubaneswar - 751001 and Printed at Orissa Government Press, Cuttack - 753010. For subscription and trade inquiry, please contact : Manager, Publications, Information & Public Relations Department, Loksampark Bhawan, Bhubaneswar - 751001. E-mail : [email protected] Five Rupees / Copy Visit : www.orissagov.nic.in Fifty Rupees / Yearly Contact : Ph. 0674-2411839 CONTENTS Editorial Landlord Sri Jagannath Mahaprabhu Bije Puri Dr. Chitrasen Pasayat ... 1 Jamesvara Temple at Puri Ratnakar Mohapatra ... 6 Vedic Background of Jagannath Cult Dr. Bidyut Lata Ray ... 15 Orissan Vaisnavism Under Jagannath Cult Dr. Braja Kishore Swain ... 18 Bhakta Kabi Sri Bhakta Charan Das and His Work Somanath Jena ... 23 'Manobodha Chautisa' The Essence of Patriotism in Temple Multiplication - Dr. Braja Kishore Padhi ... 26 Kulada Jagannath Rani Suryamani Patamahadei : An Extraordinary Lady in Puri Temple Administration Prof. Jagannath Mohanty ... 30 Sri Ratnabhandar of Srimandir Dr. Janmejaya Choudhury ... 32 Lord Jagannath of Jaguleipatna Braja Paikray ... 34 Jainism and Buddhism in Jagannath Culture Pabitra Mohan Barik ... 36 Balabhadra Upasana and Tulasi Kshetra Er. -

Y-Chromosomal and Mitochondrial SNP Haplogroup Distribution In

Open Access Austin Journal of Forensic Science and Criminology Review Article Y-Chromosomal and Mitochondrial SNP Haplogroup Distribution in Indian Populations and its Significance in Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) - A Review Based Molecular Approach Sinha M1*, Rao IA1 and Mitra M2 1Department of Forensic Science, Guru Ghasidas Abstract University, India Disaster Victim Identification is an important aspect in mass disaster cases. 2School of Studies in Anthropology, Pt. Ravishankar In India, the scenario of disaster victim identification is very challenging unlike Shukla University, India any other developing countries due to lack of any organized government firm who *Corresponding author: Sinha M, Department of can make these challenging aspects an easier way to deal with. The objective Forensic Science, Guru Ghasidas University, India of this article is to bring spotlight on the potential and utility of uniparental DNA haplogroup databases in Disaster Victim Identification. Therefore, in this article Received: December 08, 2016; Accepted: January 19, we reviewed and presented the molecular studies on mitochondrial and Y- 2017; Published: January 24, 2017 chromosomal DNA haplogroup distribution in various ethnic populations from all over India that can be useful in framing a uniparental DNA haplogroup database on Indian population for Disaster Victim Identification (DVI). Keywords: Disaster Victim identification; Uniparental DNA; Haplogroup database; India Introduction with the necessity mentioned above which can reveal the fact that the human genome variation is not uniform. This inconsequential Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) is the recognized practice assertion put forward characteristics of a number of markers ranging whereby numerous individuals who have died as a result of a particular from its distribution in the genome, their power of discrimination event have their identity established through the use of scientifically and population restriction, to the sturdiness nature of markers to established procedures and methods [1]. -

India: the Weakening of the Congress Stranglehold and the Productivity Shift in India

ASARC Working Paper 2009/06 India: The Weakening of the Congress Stranglehold and the Productivity Shift in India Desh Gupta, University of Canberra Abstract This paper explains the complex of factors in the weakening of the Congress Party from the height of its power at the centre in 1984. They are connected with the rise of state and regional-based parties, the greater acceptability of BJP as an alternative in some of the states and at the Centre, and as a partner to some of the state-based parties, which are in competition with Congress. In addition, it demonstrates that even as the dominance of Congress has diminished, there have been substantial improvements in the economic performance and primary education enrolment. It is argued that V.P. Singh played an important role both in the diminishing of the Congress Party and in India’s improved economic performance. Competition between BJP and Congress has led to increased focus on improved governance. Congress improved its position in the 2009 Parliamentary elections and the reasons for this are briefly covered. But this does not guarantee an improved performance in the future. Whatever the outcomes of the future elections, India’s reforms are likely to continue and India’s economic future remains bright. Increased political contestability has increased focus on governance by Congress, BJP and even state-based and regional parties. This should ensure improved economic and outcomes and implementation of policies. JEL Classifications: O5, N4, M2, H6 Keywords: Indian Elections, Congress Party's Performance, Governance, Nutrition, Economic Efficiency, Productivity, Economic Reforms, Fiscal Consolidation Contact: [email protected] 1. -

Political Economy of India's Fiscal and Financial Reform*

Working Paper No. 105 Political Economy of India’s Fiscal and Financial Reform by John Echeverri-Gent* August 2001 Stanford University John A. and Cynthia Fry Gunn Building 366 Galvez Street | Stanford, CA | 94305-6015 * Associate Professor, Department of Government and Foreign Affairs, University of Virginia 1 Although economic liberalization may involve curtailing state economic intervention, it does not diminish the state’s importance in economic development. In addition to its crucial role in maintaining macroeconomic stability, the state continues to play a vital, if more subtle, role in creating incentives that shape economic activity. States create these incentives in a variety of ways including their authorization of property rights and market microstructures, their creation of regulatory agencies, and the manner in which they structure fiscal federalism. While the incentives established by the state have pervasive economic consequences, they are created and re-created through political processes, and politics is a key factor in explaining the extent to which state institutions promote efficient and equitable behavior in markets. India has experienced two important changes that fundamentally have shaped the course of its economic reform. India’s party system has been transformed from a single party dominant system into a distinctive form of coalitional politics where single-state parties play a pivotal role in making and breaking governments. At the same time economic liberalization has progressively curtailed central government dirigisme and increased the autonomy of market institutions, private sector actors, and state governments. In this essay I will analyze how these changes have shaped the politics of fiscal and financial sector reform. -

Formation and Activities of the Utkal Provincial Krushak Sangha in Colonial Odisha (1935-38)

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org Volume 3 Issue 12 ǁ December. 2014 ǁ PP.46-52 Formation and Activities of the Utkal Provincial Krushak Sangha in Colonial Odisha (1935-38) Amit Kumar Nayak PhD Research Scholar, P.G. Department of History, Utkal University, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India. ABSTRACT : The peasants of Odisha came within the ambit of colonial capitalistic economic system after British conquered Odisha in 1803.Up to the end of the Civil Dis-obedience movement, the peasants in Odisha yet remained backward, retrogressive, unorganised and feudal in nature . Out of different circumstances socialism started to germinate in and later on dominated the post-Civil Disobedience movement phase Odisha.The newly indoctrinated socialist leaders took up peasants‟ cause and organised them against colonial hegemonic rule in different issues by organising a special peasants‟ organization in pan-Odishan basis. So, this article tries to locate the efforts of the socialist leaders vis-a-vis the peasants through Utkal Provincial Krushak Sangha. It also endeavours to assess the overall activities of that organisation, its tactics in mobilizing peasants in colonial Odisha from 1935 to 1938.Besides, this article also tries to present how the Utkal Provincial Krushaka Sangha was formed and how it worked as a platform for the peasants of odisha in co-ordinating, mobilising, educating and organising the agrarian community in 1930s and 1940s.. KEYWORDS : Agrarian, Krushaka , Movement, Rebellion , Sangha, , Socialist ,Utkal I. INTRODUCTION Peasants (English term for the Odia word Krushak), being a segment in the complex capitalistic farming system, are destined to fulfill its legitimate rights, according to Karl Marx, through prolonged ‗class struggle‘. -

Odisha Review Dr

Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 Index of Orissa Review (April-1948 to May -2013) Sl. Title of the Article Name of the Author Page No. No April - 1948 1. The Country Side : Its Needs, Drawbacks and Opportunities (Extracts from Speeches of H.E. Dr. K.N. Katju ) ... 1 2. Gur from Palm-Juice ... 5 3. Facilities and Amenities ... 6 4. Departmental Tit-Bits ... 8 5. In State Areas ... 12 6. Development Notes ... 13 7. Food News ... 17 8. The Draft Constitution of India ... 20 9. The Honourable Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru's Visit to Orissa ... 22 10. New Capital for Orissa ... 33 11. The Hirakud Project ... 34 12. Fuller Report of Speeches ... 37 May - 1948 1. Opportunities of United Development ... 43 2. Implication of the Union (Speeches of Hon'ble Prime Minister) ... 47 3. The Orissa State's Assembly ... 49 4. Policies and Decisions ... 50 5. Implications of a Secular State ... 52 6. Laws Passed or Proposed ... 54 7. Facilities & Amenities ... 61 8. Our Tourists' Corner ... 61 9. States the Area Budget, January to March, 1948 ... 63 10. Doings in Other Provinces ... 67 1 Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 11. All India Affairs ... 68 12. Relief & Rehabilitation ... 69 13. Coming Events of Interests ... 70 14. Medical Notes ... 70 15. Gandhi Memorial Fund ... 72 16. Development Schemes in Orissa ... 73 17. Our Distinguished Visitors ... 75 18. Development Notes ... 77 19. Policies and Decisions ... 80 20. Food Notes ... 81 21. Our Tourists Corner ... 83 22. Notice and Announcement ... 91 23. In State Areas ... 91 24. Doings of Other Provinces ... 92 25. Separation of the Judiciary from the Executive .. -

Dilemma of Resources and Resistance

:: The potential and limits of resource-rich East India Dilemma of resources and resistance Imm Jeong-Seong Senior Business Analyst of POSCO Research Institute est Bengal is located at the lower Ganges-Yamuna River. The Mahanadi River, which literally means the Great River, starts in Chhattisgarh and flows through W the states of Orissa and Jharkhand. These areas have the largest mineral reserves in India, but are usually ranked last in competitiveness. This is the region of East India. Why are the East Indian states so underprivileged? Can their situation be improved? ○● “Resource curse” East India is comprised of the coastal areas along the Bay of Bengal and the tropical inland jungles. Due to easy access, the coastal areas have been modernized quickly. Kolkata has a particularly favorable geographical location; the East India Company chose Kolkata for a British trade settlement. However, 30% of the total area of East India is mountainous, and the 061 Autumn 2011�POSRI Chindia Quarterly populations of native tribes are relatively high: 34% in Chhattisgarh, 28% in Jharkhand, and 22% in Orissa. In some remote districts, this figure is as high as 60-70%. These native tribes are isolated from modernization as well as recent economic development, and are classified as the poorest group in India. Naxalite guerillas are rampant in these mountain regions. They are most active along the meridian from the Himalayas in Nepal to Andhra Pradesh. This area is called “The Red Corridor”. The Naxalites formed in 1967 in Naxalbari, a small village in West Bengal where poor, landless farmers revolted against their rich landlords and seized the land. -

List of Colleges Affiliated to Sambalpur University

List of Colleges affiliated to Sambalpur University Sl. No. Name, address & Contact Year Status Gen / Present 2f or Exam Stream with Sanctioned strength No. of the college of Govt/ Profes Status of 12b Code (subject to change: to be verified from the Estt. Pvt. ? sional Affilia- college office/website) Aided P G ! tion Non- WC ! (P/T) aided Arts Sc. Com. Others (Prof) Total 1. +3 Degree College, 1996 Pvt. Gen Perma - - 139 96 - - - 96 Karlapada, Kalahandi, (96- Non- nent 9937526567, 9777224521 97) aided (P) 2. +3 Women’s College, 1995 Pvt. Gen P - 130 128 - 64 - 192 Kantabanji, Bolangir, Non- W 9437243067, 9556159589 aided 3. +3 Degree College, 1990 Pvt. Gen P- 2003 12b 055 128 - - - 128 Sinapali, Nuapada aided (03-04) 9778697083,6671-235601 4. +3 Degree College, Tora, 1995 Pvt. Gen P-2005 - 159 128 - - - 128 Dist. Bargarh, Non- 9238773781, 9178005393 Aided 5. Area Education Society 1989 Pvt. Gen P- 2002 12b 066 64 - - - 64 (AES) College, Tarbha, Aided Subarnapur, 06654- 296902, 9437020830 6. Asian Workers’ 1984 Pvt. Prof P 12b - - - 64 PGDIRPM 136 Development Institute, Aided 48 B.Lib.Sc. Rourkela, Sundargarh 24 DEEM 06612640116, 9238345527 www.awdibmt.net , [email protected] 7. Agalpur Panchayat Samiti 1989 Pvt. Gen P- 2003 12b 003 128 64 - - 192 College, Roth, Bolangir Aided 06653-278241,9938322893 www.apscollege.net 8. Agalpur Science College, 2001 Pvt. Tempo - - 160 64 - - - 64 Agalpur, Bolangir Aided rary (T) 9437759791, 9. Anchal College, 1965 Pvt. Gen P 12 b 001 192 128 24 - 344 Padampur, Bargarh Aided 6683-223424, 0437403294 10. Anchalik Kishan College, 1983 Pvt. -

Odisha As a Multicultural State: from Multiculturalism to Politics of Sub-Regionalism

Afro Asian Journal of Social Sciences Volume VII, No II. Quarter II 2016 ISSN: 2229 – 5313 ODISHA AS A MULTICULTURAL STATE: FROM MULTICULTURALISM TO POLITICS OF SUB-REGIONALISM Artatrana Gochhayat Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Sree Chaitanya College, Habra, under West Bengal State University, Barasat, West Bengal, India ABSTRACT The state of Odisha has been shaped by a unique geography, different cultural patterns from neighboring states, and a predominant Jagannath culture along with a number of castes, tribes, religions, languages and regional disparity which shows the multicultural nature of the state. But the regional disparities in terms of economic and political development pose a grave challenge to the state politics in Odisha. Thus, multiculturalism in Odisha can be defined as the territorial division of the state into different sub-regions and in terms of regionalism and sub- regional identity. The paper attempts to assess Odisha as a multicultural state by highlighting its cultural diversity and tries to establish the idea that multiculturalism is manifested in sub- regionalism. Bringing out the major areas of sub-regional disparity that lead to secessionist movement and the response of state government to it, the paper concludes with some suggestive measures. INTRODUCTION The concept of multiculturalism has attracted immense attention of the academicians as well as researchers in present times for the fact that it not only involves the question of citizenship, justice, recognition, identities and group differentiated rights of cultural disadvantaged minorities, it also offers solutions to the challenges arising from the diverse cultural groups. It endorses the idea of difference and heterogeneity which is manifested in the cultural diversity. -

Sub Regionalism Politics in Odisha and Demand for Koshal State

International Journal of Academic Research ISSN: 2348-7666; Vol.4, Issue-5(1), May, 2017 Impact Factor: 4.535; Email: [email protected] Sub Regionalism Politics in Odisha and Demand for Koshal State Dr. Dasarathi Bhuiyan, Assistant Professor, P.G. Department of Political Science, Berhampur University, Odisha Abstract: This paper examines the rise of regionalism in Odisha. As a state, Odisha is one of the most backward regions in India. The process of development becomes extremely significant in the context of intra-regional disparities. Against this backdrop, regionalism continues to thrive in western Odisha due to regional cleavages and prevalence of socio-economic disparities and political inequalities. Key words: historical experience, cultural practices, dialectal/speech forms I. Introduction regional polarisation of politics was very much reflected in the elections to the The present state of Odisha Odisha Legislative Assembly. As contains three geographically distinct discussed above during the 1950’s the regional units, namely, coastal belt, regional political parties, namely, the southern and western region, which Ganatantra Parishad (GP) and later the differ in respect of historical experience, Swatantra party polarised politics in cultural practices, dialectal/speech forms, Odisha along regional lines. The political advantages and socio-economic Congress was seen as a party largely development. After the reorganisation of identified with the interests of coastal districts in Odisha in 1993 the coastal Odisha, and the GP/Swatantra was region comprises the new districts of associated with the interests of western Balasore, Bhadrak, Cuttack, Jajpur, Odisha. From 1952 to 1974, the Congress Kendrapara, Jagatsinghpur, Puri, and its splinter groups Jana Congress Khordha, Nayagarh, the south Odisha and Utkal Congress secured maximum comprises of Ganjam, Gaiapati, seats from coastal districts, while Kandhamal, Koraput, Rayagarda, GP/Swatantra scored very well in the Nawarangapur, Malkangiri; whereas the western region (Ray 1974). -

(Ph. D. Thesis) March, 1990 Takako Hirose

THE SINGLE DOMINANT PARTY SYSTEM AND POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT: CASE STUDIES OF INDIA AND JAPAN (Ph. D. Thesis) March, 1990 Takako Hirose ABSTRACT This is an attempt to compare the processes of political development in India and Japan. The two states have been chosen because of some common features: these two Asian countries have preserved their own cultures despite certain degrees of modernisation; both have maintained a system of parliamentary democracy based on free electoral competition and universal franchise; both political systems are characterised by the prevalence of a single dominant party system. The primary objective of this analysis is to test the relevance of Western theories of political development. Three hypotheses have been formulated: on the relationship between economic growth and social modernisation on the one hand and political development on the other; on the establishment of a "nation-state" as a prerequisite for political development; and on the relationship between political stability and political development. For the purpose of testing these hypotheses, the two countries serve as good models because of their vastly different socio-economic conditions: the different levels of modernisation and economic growth; the homogeneity- heterogeneity dichotomy; and the frequency of political conflict. In conclusion, Japan is an apoliticised society in consequence of the imbalance between its political and economic development. By contrast, the Indian political system is characterised by an ever-increasing demand for - 2 - participation, with which current levels of institutionalisation cannot keep pace. The respective single dominant parties have thus played opposing roles, i.e. of apoliticising society in the case of Japan while encouraging participation in that of India.