Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12. What We Talk About When We Talk About Indian

12. What we talk about when we talk about Indian Yvette Nolan here are many Shakespearean plays I could see in a native setting, from A Midsummer Night’s Dream to Coriolanus, but Julius Caesar isn’t one of them’, wrote Richard Ouzounian in the Toronto Star ‘Tin 2008. He was reviewing Native Earth Performing Arts’ adaptation of Julius Caesar, entitled Death of a Chief, staged at Buddies in Bad Times Theatre, Toronto. Ouzounian’s pronouncement raises a number of questions about how Indigenous creators are mediated, and by whom, and how the arbiter shapes the idea of Indigenous.1 On the one hand, white people seem to desire a Native Shakespeare; on the other, they appear to have a notion already of what constitutes an authentic Native Shakespeare. From 2003 to 2011, I served as the artistic director of Native Earth Performing Arts, Canada’s oldest professional Aboriginal theatre company. During my tenure there, we premiered nine new plays and a trilingual opera, produced six extant scripts (four of which we toured regionally, nationally or internationally), copresented an interdisciplinary piece by an Inuit/Québecois company, and created half a dozen short, made-to-order works, community- commissioned pieces to address specific events or issues. One of the new plays was actually an old one, the aforementioned Death of a Chief, which we coproduced in 2008 with Canada’s National Arts Centre (NAC). Death, an adaptation of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, took three years to develop. Shortly after I started at Native Earth, Aboriginal artists approached me about not being considered for roles in Shakespeare (unless producers were doing Midsummer Night’s Dream, because apparently fairies can be Aboriginal, or Coriolanus, because its hero struggles to adapt to a consensus-based community). -

Reader's Digest Canada

MOST READ MOST TRUSTED SEPTEMBER 2015 A ROYAL RECORD PAGE 56 HOW TO GREEK BOOST FERRY LEARNING DISASTER PAGE 70 PAGE 78 TIPS FOR A HEALTHY BEDROOM PAGE 102 WORRY: IT’S GOOD FOR YOU! PAGE 27 WHEN TO BUY ORGANIC PAGE 40 BE NICE TO YOUR KNEES .................................. 30 MIND-BENDING PUZZLES ................................ 129 LAUGHTER, THE BEST MEDICINE ..................... 68 ALL THE CRITICS SAY “YEAH!” THE REVIEWS ARE IN... “ SPECTACULAR CELEBRATION!” Richard Ouzounian, Toronto Star “FABULOUS, FUNNY “ONE OF THE BEST & FANTASTIC! MUSICALS I’VE EVER SEEN. DON’T MISS THIS ONE!” KINKYs crazy BOOTSgood.” i Jennifer Valentyne, Breakfast Television Steve Paikin, TVO A NEW MUSICAL BASED ON A TRUE STORY Tiedemann Von Cylla “A FEEL GOOD SHOW. by YOU LEAVE THE THEATRE WITH A BIG SMILE ON YOUR FACE Photos and a bounce in your high-heeled step!” Carolyn MacKenzie, Global TV NOWN STAGE O ROYAL ALEXANDRA THEATRE 260 KING STREET WEST, TORONTO 1-800-461-3333 MIRVISH.COM ALAN MINGO JR. AJ BRIDEL & GRAHAM SCOTT FLEMING Contents SEPTEMBER 2015 Cover Story 56 Mighty Monarch On September 9, Queen Elizabeth II becomes the longest-reigning ruler in British history. A Canadian look back. STÉPHANIE VERGE Society 62 Cash-Strapped Payday loans are a lifeline for low-income Canadians—but at what cost? CHRISTOPHER POLLON FROM THE WALRUS Science 70 Know Better New ways to improve your ability to learn. DANIELLE GROEN AND KATIE UNDERWOOD Drama in Real Life 78 Ship Down P. A Greek family fight to survive when their ferry | 70 goes up in flames. KATHERINE LAIDLAW Humour 86 The Endless Steps David Sedaris on becoming obsessed with Fitbit. -

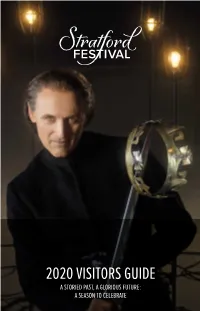

2020 Visitors Guide a Storied Past, a Glorious Future: a Season to Celebrate the Elixir of Power

2020 VISITORS GUIDE A STORIED PAST, A GLORIOUS FUTURE: A SEASON TO CELEBRATE THE ELIXIR OF POWER Irresistible – that’s the only way to describe the variety, quality and excitement that make up the Stratford Festival’s 2020 season. First, there is our stunning new Tom Patterson Theatre, with ravishingly beautiful public spaces and gardens. Its halls, bars and café will be filled throughout the season with music, comedy nights, panel discussions and outstanding speakers to make our Festival even more festive. In the wake of an election in Canada, and in anticipation of one in the U.S., our season explores the theme of Power. Recent years have seen a growing acceptance of the naked use of power. Brute force is in vogue on the world stage, from international trade to immigration and the arms race – and, closer to home, in elections, in the workplace and even in social media engagements. Through comedy, tragedy, song, dance and farce, the plays and musicals of our 2020 season explore the dynamics of power in society, politics, art, gender and family life. In our new Tom Patterson Theatre, we present the two plays that launched the Stratford adventure in 1953: All’s Well That Ends Well and Richard III. The new venue is also home to a new musical, Here’s What It Takes; a new movement-based creation, Frankenstein Revived; and a series of improvisational performances – each one unique and unrepeatable – called An Undiscovered Shakespeare. But the fun isn’t all confined to one theatre. Our historic Festival Theatre showcases two of Shakespeare’s greatest plays, Much Ado About Nothing and Hamlet, as well as Molière’s brilliant satire The Miser and the first major new production in decades of the mischievous musical Chicago. -

SUBMISSION RE-EDIT Caitlin Thompson Dissertation 2019

Making ‘fritters with English’: Functions of Early Modern Welsh Dialect on the English Stage by Caitlin Thompson A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Drama, Theatre, and Performance Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Caitlin Thompson 2019 Making ‘fritters with English’: Functions of Early Modern Welsh Dialect on the English Stage Caitlin Thompson Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Drama, Theatre, and Performance Studies University of Toronto 2019 ABSTRACT The Welsh had a unique status as paradoxically familiar ‘foreigners’ throughout early modern London; Henry VIII actively suppressed the use of the Welsh language, even though many in the Tudor line selectively boasted of Welsh ancestry. Still, in the late-sixteenth century, there was a surge in London’s Welsh population which coincided with the establishment of the city’s commercial theatres. This timely development created a stage for English playwrights to dramatically enact the complicated relationship between the nominally unified nations. Welsh difference was often made theatrically manifest through specific dialect conventions or codified and inscrutable approximate Welsh language. This dissertation expands upon critical readings of Welsh characters written for the English stage by scholars such as Philip Schwyzer, Willy Maley, and Marissa Cull, to concentrate on the vocal and physical embodiments of performed Welshness and their functions in contemporary drama. This work begins with a historicist reading of literary and political Anglo-Welsh relations to build a clear picture of the socio-historical context from which Welsh characters of the period were constructed. The plays which form the focus of this work range from popular plays like Shakespeare’s Henry V (1599) to lesser-known works from Thomas Nashe’s Summer’s Last Will and Testament (1592) to Thomas Dekker’s The Welsh Embassador ii (1623) which illuminate the range of Welsh presentations in early modern England. -

Djanet Sears's Appropriations of Shakespeare in Harlem Duet

The Dramaturgy of Appropriation: How Canadian Playwrights Use and Abuse Shakespeare and Chekhov by James Stuart McKinnon A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Centre for the Study of Drama University of Toronto © Copyright by James McKinnon 2010 The Dramaturgy of Appropriation: How Canadian Playwrights Use and Abuse Shakespeare and Chekhov James Stuart McKinnon Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Centre for the Study of Drama University of Toronto 2010 Abstract Both theatre and drama were imported to Canada from European colonizing nations, and as such the canonical master-texts of European drama, particularly the works of Shakespeare, have always occupied a prominent place in Canadian theatre. This presents a challenge for living Canadian playwrights, whose most revered role model is also their most dangerous competition, and whose desire to represent the spectrum of contemporary Canadian experience on stage is often at odds with the preferences of many producers and spectators for the ―classics.‖ Since the 1990s, a number of Canadian playwrights have attempted to challenge the role of canonical plays and the values they represent by appropriating and critiquing them in plays of their own, creating a body of work which disturbs conventional distinctions between ―adaptations‖ and ―originals.‖ This study describes and analyzes the adaptive dramaturgies used by recent Canadian playwrights to appropriate canonical plays, question the privileged place they occupy in Canadian culture, expose the exclusionary hierarchies they legitimate, and claim centre stage for Canadian perspectives which have hitherto been waiting in the wings. It examines how playwrights challenge, usurp, or exploit the cultural capital of the canon by ―re-citing‖ old plays ii in new works, how they or their producers attempt to frame the reception of their plays in order to address cultural biases against adaptation, and how audiences respond. -

Toronto Star – the Shaman Review

Evelyn Glennie true musical shaman at New Creations Festival - thestar.com 11-04-01 11:01 PM Friday, April 1, 2011 Connect with Facebook | Login/Register 2°C Forecast | Traffic thestar.com Web find a business advanced search full text article archive Home News GTA Opinion Business Sports Entertainment Life Travel Columns Blogs More Autos Careers Classifieds Deaths Rentals HOT TOPICS ONTARIO BUDGET LEAFS JAPAN EARTHQUAKE ARAB AWAKENING ROYAL WEDDING TORONTO FASHION WEEK POLITICS PAGE BLUE JAYS Home Entertainment Music Inside thestar.com Rewind: The week in Montrealer loves Back to square one Trudeau's porn Veteran MPP loses review being on Mad Men for TFC foolery nomination - Advertisement - Evelyn Glennie true musical shaman at New Creations Festival Article Published On Wed Mar 02 2011 Email Print Share 40 By John Terauds Entertainment Reporter Itʼs safe to say Peter Oundjianʼs most notable accomplishment as music director of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra has been the annual New Creations Festival. The maestro launched the first of three concerts that make up the seventh edition of the Sponsored Links festival in fiery form on Wednesday night at Roy Thomson Hall. Draw closer to God Subscribe to Living with Christ, your Every year, the focus is on the work of one composer, and Oundjian and his colleagues daily spiritual companion. www.Novalis.ca have a knack for programming music and guest performers who can fire up the audienceʼs Brain Training Games imagination. Improve memory with scientifically designed brain exercises-Free Trial www.lumosity.com This yearʼs New Creations Festival puts the spotlight on American composer John Adams — one of the most successful living composers in the world right now. -

Democratic Primary • Silence on Secrecy 2 February 13 — 26, 2020 View View February 13 — 26, 2020 3 Love & Sex Guide 13 Sex in the Cinema

GREATER HAMILTON’S INDEPENDENT VOICE FEBRUARY 13 — 26, 2020 VOL. 26 NO. 6 Into da Future HEALTH & WELLNESS: VEGAN LIFESTLYE • DIGITAL HEALTH • PERSPECTIVE: DEMOCRATIC PRIMARY • SILENCE ON SECRECY 2 FEBRUARY 13 — 26, 2020 VIEW VIEW FEBRUARY 13 — 26, 2020 3 LOVE & SEX GUIDE 13 SEX IN THE CINEMA INSIDE THIS ISSUE FEBRUARY 13 — 26, 2020 19 COVER HARLEY QUINN FORUM THEATRE 05 PERSPECTIVE 07 REVIEW The Beauty Queen... Democratic Primary 06 CATCH FOOD 12 Dining Guide MUSIC 08 Hamilton Music Notes ETC. 14 Live Music Listings 11 HEALTH & WELLNESS 13 LOVE & SEX GUIDE MOVIES 22 General Classifieds 19 REVIEW Harley Quinn 22-23 FREE WILL ASTROLOGY 20 Mini Movie Reviews 23 Adult Classifieds 370 MAIN STREET WEST, HAMILTON, ONTARIO L8P 1K2 HAMILTON 905.527.3343 FAX 905.527.3721 VIEW FOR ADVERTISING INQUIRIES: 905.527.3343 X102 EDITOR IN CHIEF Ron Kilpatrick x109 [email protected] OPERATIONS DIRECTOR CLASSIFIED ADVERTISING ACCOUNTING PUBLISHER Marcus Rosen x101 Liz Kay x100 Roxanne Green x103 Sean Rosen x102 [email protected] 1.866.527.3343 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ADVERTISING DEPT DISTRIBUTION CONTRIBUTORS LISTINGS EDITOR RandA distribution Rob Breszny • Gregory SENIOR CORPORATE Alison Kilpatrick x100 Owner:Alissa Ann latour Cruikshank • Sara Cymbalisty • REPRESENTATIVE [email protected] Manager:Luc Hetu Maxie Dara • Albert DeSantis • Ian Wallace x107 905-531-5564 Darrin DeRoches • Daniel [email protected] HAMILTON MUSIC NOTES [email protected] Gariépy • Allison M. Jones • Tamara Kamermans • Michael Ric Taylor Klimowicz • Don McLean ADVERTISING [email protected] PRINTING • Brian Morton • Ric Taylor • REPRESENTATIVE MasterWeb Printing Michael Terry Al Corbeil x105 PRODUCTION [email protected] [email protected] PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT NO. -

Téléchargez La Version

Société canadienne des postes — Envois de publication convention nº. 40025257 gratuitCanada Post Publications / freeMail Sales Agreement nº. 40025257 music for you music for your every mood and moment Music For You is a brand new series that allows you to create the perfect audio environment -- any time, any mood. Whether you're looking to relax and reflect or be roused and inspired, Music For You features titles that complement and enhance your every experience. la musique pour votre état d'âme «Music For You», une nouvelle série qui vous permet de créer un environnement sonore parfait - n'importe quand, n'importe quel état d'âme. Si vous cherchez à réfléchir et à vous détendre ou à vous stimuler et inspirer, «Music For You» comporte des titres pour accompagner et appuyer vos réalisations also available également disponible yo-yo ma: dvorak cello concerto jack martin handler: haydn - london symphonies miles davis blue moods yo-yo ma plays bach riri shimada: Sultry and expressive. Journey into the ether of Robust. Dignified. Awaken your finer erik satie piano works your most passionate emotions. sensibilities with the pleasures of sheer Sensuel et expressif. Un voyage éthéré à travers elegance. murray perahia: vos émotions les plus passionnées. Robuste. Digne. Réveillez votre plus brahms - intermezzo subtile sensibilité avec élégance. carlo maria giulini: mozart - requiem john tilbury: howard skempton - piano works dave brubeck ballads emanuel ax haydn piano concertos Sentimental and serene,Brubeck's music is the Lively, bright and ever lighthearted, there perfect accent for that blissful evening for two. may be no better way to jumpstart your day. -

Support for the 2019 Season of the Avon Theatre Is Generously Provided by the Birmingham Family Production Support Is Generously Provided by Sylvia D

SUPPORT FOR THE 2019 SEASON OF THE AVON THEATRE IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY THE BIRMINGHAM FAMILY PRODUCTION SUPPORT IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY SYLVIA D. CHROMINSKA, BY MARTIE & BOB SACHS, BY ALICE & TIM THORNTON AND BY THE TREMAIN FAMILY 2 DIRECTOR’S NOTE A CRUCIBLE OF CREATION BY JONATHAN GOAD Crucible | ˈkro͞osəb(ə)l noun 1. A container in which metals or other substances may be melted, purified or subjected to extremely high temperatures 2. A situation of severe trial leading to the creation of something new 3. A severe, searching test or trial 4. The Crucible, a play by Arthur Miller Working on this play with a group of sensitive, committed artists has been a privilege both terrific and terrifying. Just as Arthur Miller spied a “poetry in the hunt” when he set out to write The Crucible, the actors find poetry (pleasure, excitement, meaning) in the ritual of rediscovering the harrowing events of the play each time they play it. The pleasure is in playing – even with a work that examines many grim and brutal recesses of the human journey and condition. I am grateful to this company for undertaking this ritual of work/ play with such heart and guts. 9 HOLY ACCUSERS BY CRAIG WALKER In his 1987 memoir, Timebends, Arthur ten-year-old daughter of Reverend Samuel Miller says of The Crucible, his most- Parris, and her cousin, Abigail Williams, produced play: began to have fits. Soon, other girls in the village were complaining of similar symptoms. The girls claimed they were “Its meaning is somewhat different in bewitched; they blamed Tituba, a slave different places and moments. -

Dead Metaphor Words on Plays (2013)

AMERICAN CONSERVATORY THEATER .!5ƫ!.(+""Čƫ.0%/0%ƫ%.!0+.ƫđƫ((!*ƫ%$. Čƫ4!10%2!ƫ%.!0+. PRESENTS Dead Metaphor by George F. Walker Directed by Irene Lewis The Geary Theater February 28–March 24, 2013 WORDS ON PLAYS vol. xix, no. 4 Dan Rubin Editor Elizabeth Brodersen Director of Education Michael Paller Resident Dramaturg Amy Krivohlavek Marketing Writer Cait Robinson Publications Fellow Made possible by © 2013 AMERICAN CONSERVATORY THEATER, A NONPROFIT ORGANIZATION. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Table of Contents 1 Characters, Cast, and Synopsis of Dead Metaphor 3 “These Are My People” Exploring “Walker Realism” with Director Irene Lewis by Amy Krivohlavek 9 Seeing the World through the Eyes of a Sniper An Interview with Scenic Designer Christopher Barreca by Dan Rubin 13 Laugh Lest You Go Insane A Conversation with Playwright George F. Walker by Dan Rubin 27 A Weapon First, A Person Second A Sniper’s Life by Cait Robinson 31 A Few Good Jobs Returning Veterans Struggle to Find Work by Cait Robinson 35 How Metaphors Die 36 Questions to Consider / For Further Information . COVER Trigger Finger (detail)ČƫāĊćăƫįƫ/00!ƫ+"ƫ+5ƫ %$0!*/0!%* OPPOSITE American Sporting Scene: Snipe ShootingƫĨ !0%(ĩČƫ ,1(%/$! ƫ5ƫ +$*ƫ(/$ƫĒƫ+ċČƫāĉĈĀƫĨ %..5ƫ+"ƫ+*#.!//ĩċƫ+.ƫ)+.!ƫ +*ƫė/*%,!.Ęƫ/ƫƫ ! ƫ)!0,$+.Čƫ/!!ƫ,#!ƫăĆċ !0ƫ!(!20%+*ƫ"+.ƫ 36'-0" >*,250 of%;85:*+4.29 4*,3#;++.82,3"4*:. 9" ELEVATION Dead Metaphor >#2509;8/*,.9*8.,*87.:.- Čƫ5ƫ/!*%ƫ !/%#*!.ƫ$.%/0+,$!.ƫ..! *87.:$:=4. #2509 5,6, & 9 NOTE: >#250 529/2<.- *87.:$:=4. >#250 697259 both-28.,:2659 #2509 7,8 & >#250 7 / 89725 both-28.,:2659 .5:.8 >#250 9 &,.5:.8,28,4.*8./2<.- 36'-0" >&9..:*4 69250 /686;:.88250.-0. -

THE BIRTH of the FREDERIC WOOD THEATRE How the Early

THE BIRTH OF THE FREDERIC WOOD THEATRE How The Early Development of the University of British Columbia Fostered the Establishment of the Theatre Department and the Frederic Wood Theatre By MARILYN LEIGH BENSON B.F.A., The University of British Columbia, 1984 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Theatre) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA July 1991 (c) Marilyn Leigh Benson, 1991 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada DE-6 (2/88) ii ABSTRACT It has been said that the character of an institution is largely determined by its history and the personalities that shaped it. If this is so, the Frederic Wood Theatre has much to draw on, for it was founded in the spirit of cooperation and promise. This thesis traces the beginning of the university from the original petition for its formation, through its early struggle to be established. Concurrent with this expansion is the growth of theatre at the university, a development which helped to introduce the institution throughout the province. -

Knowing Ways in the Digital Age: Indigenous Knowledge and Questions of Sharing from Idle No More to the Unplugging

ARTICLES Knowing Ways in the Digital Age: Indigenous Knowledge and Questions of Sharing from Idle No More to The Unplugging Kimberley McLeod Unlike other minorities, questions of the Digital Age look different from the perspective of people struggling to control land and traditions that have been appropriated by now dominant settler societies for as long as 500 years. —Faye Ginsburg It’s not over. We’re not over. —Yvette Nolan, The Unplugging At the end of 2012, the Idle No More movement burst onto the public stage. Within a month, what had begun with modest teach-ins organized by four Saskatchewan women had quickly morphed into a national—and even international—movement broadly promoting Indigenous Sovereignty, empowerment, and recognition. The movement started as a means to oppose Bill C-45, legislation put forward by Canada’s then-Conservative government. The 450-page omnibus bill included several proposals members of Idle No More considered detrimental to Indigenous communities. In particular, the women who began Idle No More were concerned about changes to Canada’s Indian Act—an often maligned statute that sets the framework for the federal government’s relationship with Indigenous peoples. Bill C-45 would have altered the Act to adjust how reserve territory could be surrendered and leased. It would also have changed the Environmental Assessment and Navigable Waters Protection Acts, removing environmental assessment requirements from some projects. In opposition to the bill, on December 10, 2012 Idle No More organized their first National Day of Action, which attracted thousands of participants and seized the attention of media across Canada.