Djanet Sears's Appropriations of Shakespeare in Harlem Duet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12. What We Talk About When We Talk About Indian

12. What we talk about when we talk about Indian Yvette Nolan here are many Shakespearean plays I could see in a native setting, from A Midsummer Night’s Dream to Coriolanus, but Julius Caesar isn’t one of them’, wrote Richard Ouzounian in the Toronto Star ‘Tin 2008. He was reviewing Native Earth Performing Arts’ adaptation of Julius Caesar, entitled Death of a Chief, staged at Buddies in Bad Times Theatre, Toronto. Ouzounian’s pronouncement raises a number of questions about how Indigenous creators are mediated, and by whom, and how the arbiter shapes the idea of Indigenous.1 On the one hand, white people seem to desire a Native Shakespeare; on the other, they appear to have a notion already of what constitutes an authentic Native Shakespeare. From 2003 to 2011, I served as the artistic director of Native Earth Performing Arts, Canada’s oldest professional Aboriginal theatre company. During my tenure there, we premiered nine new plays and a trilingual opera, produced six extant scripts (four of which we toured regionally, nationally or internationally), copresented an interdisciplinary piece by an Inuit/Québecois company, and created half a dozen short, made-to-order works, community- commissioned pieces to address specific events or issues. One of the new plays was actually an old one, the aforementioned Death of a Chief, which we coproduced in 2008 with Canada’s National Arts Centre (NAC). Death, an adaptation of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, took three years to develop. Shortly after I started at Native Earth, Aboriginal artists approached me about not being considered for roles in Shakespeare (unless producers were doing Midsummer Night’s Dream, because apparently fairies can be Aboriginal, or Coriolanus, because its hero struggles to adapt to a consensus-based community). -

Theeditor-Epk.Pdf

Directed by Adam Brooks and Matthew Kennedy Written by Adam Brooks, Matthew Kennedy and Conor Sweeney Produced by Social Media sales Adam Brooks and Matthew Kennedy Twitter Producer’s Reps @theeditormovie Starring @astron6 Nate Bolotin Paz de la Huerta [email protected] Adam Brooks Facebook 310 909 9318 Facebook.com/editormovie Laurence R. Harvey Facebook.com/astron6 Mette-Marie Katz Samantha Hill [email protected] Udo Kier INTERWeb 323 983 1201 Jerry Wasserman www.theeditormovie.com Matthew Kennedy International Sales www.astron-6.com Conor Sweeney Dan Bern Paul Howell Tristan Risk CONTACT [email protected] Brett Donahue Kennedy/Brooks Inc. +44 (0)207 434 4176 738-3085 Pembina Hwy. Brent Neale Winnipeg MB R3T4R6 Sheila E. Campbell Kevin Anderson Matthew Kennedy Jasmine Mae [email protected] Tech Details Adam Brooks 99 min | Color | DCP | 2.39:1 | 5.1 | Canada | 2014 [email protected] LOGLINE A once-prolific film editor finds himself the prime suspect in a series of murders haunting a seedy 1970s film studio in this absurdist throwback to the Italian Giallo. SYNOPSIS Rey Ciso was once the greatest editor the world had ever seen. Since a horrific accident left him with four wooden fingers on his right hand, he’s had to resort to cutting pulp films and trash pictures. When the lead actors from the film he’s been editing turn up murdered at the studio, Rey is fingered as the number one suspect. The bodies continue to pile up in this absurdist giallo-thriller as Rey struggles to prove his innocence and learn the sinister truth lurking behind the scenes. -

The Mercurian

The Mercurian : : A Theatrical Translation Review Volume 4, Number 4 Editor: Adam Versényi Editorial Assistant: Michaela Morton The Mercurian is named for Mercury who, if he had known it, was/is the patron god of theatrical translators, those intrepid souls possessed of eloquence, feats of skill, messengers not between the gods but between cultures, traders in images, nimble and dexterous linguistic thieves. Like the metal mercury, theatrical translators are capable of absorbing other metals, forming amalgams. As in ancient chemistry, the mercurian is one of the five elementary “principles” of which all material substances are compounded, otherwise known as “spirit”. The theatrical translator is sprightly, lively, potentially volatile, sometimes inconstant, witty, an ideal guide or conductor on the road. The Mercurian publishes translations of plays and performance pieces from any language into English. The Mercurian also welcomes theoretical pieces about theatrical translation, rants, manifestos, and position papers pertaining to translation for the theatre, as well as production histories of theatrical translations. Submissions should be sent to: Adam Versényi at [email protected] or by snail mail: Adam Versényi, Department of Dramatic Art, CB# 3230, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3230. For translations of plays or performance pieces, unless the material is in the public domain, please send proof of permission to translate from the playwright or original creator of the piece. Since one of the primary objects of The Mercurian is to move translated pieces into production, no translations of plays or performance pieces will be published unless the translator can certify that he/she has had an opportunity to hear the translation performed in either a reading or another production-oriented venue. -

Macbeth on Three Levels Wrap Around a Deep Thrust Stage—With Only Nine Rows Dramatis Personae 14 Separating the Farthest Seat from the Stage

Weird Sister, rendering by Mieka Van Der Ploeg, 2019 Table of Contents Barbara Gaines Preface 1 Artistic Director Art That Lives 2 Carl and Marilynn Thoma Bard’s Bio 3 Endowed Chair The First Folio 3 Shakespeare’s England 5 Criss Henderson The English Renaissance Theater 6 Executive Director Courtyard-Style Theater 7 Chicago Shakespeare Theater is Chicago’s professional theater A Brief History of Touring Shakespeare 9 Timeline 12 dedicated to the works of William Shakespeare. Founded as Shakespeare Repertory in 1986, the company moved to its seven-story home on Navy Pier in 1999. In its Elizabethan-style Courtyard Theater, 500 seats Shakespeare's Macbeth on three levels wrap around a deep thrust stage—with only nine rows Dramatis Personae 14 separating the farthest seat from the stage. Chicago Shakespeare also The Story 15 features a flexible 180-seat black box studio theater, a Teacher Resource Act by Act Synopsis 15 Center, and a Shakespeare specialty bookstall. In 2017, a new, innovative S omething Borrowed, Something New: performance venue, The Yard at Chicago Shakespeare, expanded CST's Shakespeare’s Sources 18 campus to include three theaters. The year-round, flexible venue can 1606 and All That 19 be configured in a variety of shapes and sizes with audience capacities Shakespeare, Tragedy, and Us 21 ranging from 150 to 850, defining the audience-artist relationship to best serve each production. Now in its thirty-second season, the Theater has Scholars' Perspectives produced nearly the entire Shakespeare canon: All’s Well That Ends -

Othello and Its Rewritings, from Nineteenth-Century Burlesque to Post- Colonial Tragedy

Black Rams and Extravagant Strangers: Shakespeare’s Othello and its Rewritings, from Nineteenth-Century Burlesque to Post- Colonial Tragedy Catherine Ann Rosario Goldsmiths, University of London PhD thesis 1 Declaration I declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own. 2 Acknowledgements Firstly, I want to thank my supervisor John London for his immense generosity, as it is through countless discussions with him that I have been able to crystallise and evolve my ideas. I should also like to thank my family who, as ever, have been so supportive, and my parents, in particular, for engaging with my research, and Ebi for being Ebi. Talking things over with my friends, and getting feedback, has also been very helpful. My particular thanks go to Lucy Jenks, Jay Luxembourg, Carrie Byrne, Corin Depper, Andrew Bryant, Emma Pask, Tony Crowley and Gareth Krisman, and to Rob Lapsley whose brilliant Theory evening classes first inspired me to return to academia. Lastly, I should like to thank all the assistance that I have had from Goldsmiths Library, the British Library, Senate House Library, the Birmingham Shakespeare Collection at Birmingham Central Library, Shakespeare’s Birthplace Trust and the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive. 3 Abstract The labyrinthine levels through which Othello moves, as Shakespeare draws on myriad theatrical forms in adapting a bald little tale, gives his characters a scintillating energy, a refusal to be domesticated in language. They remain as Derridian monsters, evading any enclosures, with the tragedy teetering perilously close to farce. Because of this fragility of identity, and Shakespeare’s radical decision to have a black tragic protagonist, Othello has attracted subsequent dramatists caught in their own identity struggles. -

Reader's Digest Canada

MOST READ MOST TRUSTED SEPTEMBER 2015 A ROYAL RECORD PAGE 56 HOW TO GREEK BOOST FERRY LEARNING DISASTER PAGE 70 PAGE 78 TIPS FOR A HEALTHY BEDROOM PAGE 102 WORRY: IT’S GOOD FOR YOU! PAGE 27 WHEN TO BUY ORGANIC PAGE 40 BE NICE TO YOUR KNEES .................................. 30 MIND-BENDING PUZZLES ................................ 129 LAUGHTER, THE BEST MEDICINE ..................... 68 ALL THE CRITICS SAY “YEAH!” THE REVIEWS ARE IN... “ SPECTACULAR CELEBRATION!” Richard Ouzounian, Toronto Star “FABULOUS, FUNNY “ONE OF THE BEST & FANTASTIC! MUSICALS I’VE EVER SEEN. DON’T MISS THIS ONE!” KINKYs crazy BOOTSgood.” i Jennifer Valentyne, Breakfast Television Steve Paikin, TVO A NEW MUSICAL BASED ON A TRUE STORY Tiedemann Von Cylla “A FEEL GOOD SHOW. by YOU LEAVE THE THEATRE WITH A BIG SMILE ON YOUR FACE Photos and a bounce in your high-heeled step!” Carolyn MacKenzie, Global TV NOWN STAGE O ROYAL ALEXANDRA THEATRE 260 KING STREET WEST, TORONTO 1-800-461-3333 MIRVISH.COM ALAN MINGO JR. AJ BRIDEL & GRAHAM SCOTT FLEMING Contents SEPTEMBER 2015 Cover Story 56 Mighty Monarch On September 9, Queen Elizabeth II becomes the longest-reigning ruler in British history. A Canadian look back. STÉPHANIE VERGE Society 62 Cash-Strapped Payday loans are a lifeline for low-income Canadians—but at what cost? CHRISTOPHER POLLON FROM THE WALRUS Science 70 Know Better New ways to improve your ability to learn. DANIELLE GROEN AND KATIE UNDERWOOD Drama in Real Life 78 Ship Down P. A Greek family fight to survive when their ferry | 70 goes up in flames. KATHERINE LAIDLAW Humour 86 The Endless Steps David Sedaris on becoming obsessed with Fitbit. -

Alfred Hitchcock's the 39 STEPS

Alfred Hitchcock's THE 39 STEPS Play Guide Arizona Theatre Company Play Guide 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Alfred Hitchcock's THE 39 STEPS 3 WHO WE ARE 19 COMMEDIA DELL’ARTE AND LAZZI 21 PASTICHE CONTENTS 4 INTRODUCTION TO THE PLAY 4 SYNOPSIS 21 DISCUSSION QUESTIONS AND ACTIVITIES 5 THE CHARACTERS 6 JOHN BUCHAN 7 ALFRED HITCHCOCK 8 HOW ALFRED HITCHCOCK'S THE 39 STEPS CAME TO BE 10 RICHARD HANNAY – THE JAMES BOND OF HIS DAY 11 LOCATION, LOCATION, LOCATION 12 BRITAIN IN 1935 13 BRITISH DIALECTS 15 HISTORY OF FARCE It is Arizona Theatre Company’s goal to share the enriching experience of live theatre. This play guide is intended to help you prepare for your visit to Arizona Theatre Company. Should you have comments or suggestions regarding the play guide, or if you need more information about scheduling trips to see an ATC production, please feel free to contact us: Tucson: April Jackson Phoenix: Cale Epps Associate Education Manager Education Manager (520) 884-8210 ext 8506 (602) 256-6899 ext 6503 (520) 628-9129 fax (602) 256-7399 fax Alfred Hitchcock's THE 39 STEPS Play Guide compiled and written by Jennifer Bazzell, Literary Manager and Katherine Monberg, Artistic Intern. Discussion questions and activities prepared by April Jackson, Associate Education Manager and Amber Tibbitts, Education Manager. Layout by Gabriel Armijo. Support for ATC’s Education and Community Programming has been provided by: Organizations Mrs. Laura Grafman Ms. Norma Martens APS Individuals Kristie Graham Hamilton McRae Arizona Commission on the Arts Ms. Jessica L. Andrews and Mr. and Mrs. -

Sources of Lear

Meddling with Masterpieces: the On-going Adaptation of King Lear by Lynne Bradley B.A., Queen’s University 1997 M.A., Queen’s University 1998 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of English © Lynne Bradley, 2008 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photo-copying or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Meddling with Masterpieces: the On-going Adaptation of King Lear by Lynne Bradley B.A., Queen’s University 1997 M.A., Queen’s University 1998 Supervisory Committee Dr. Sheila M. Rabillard, Supervisor (Department of English) Dr. Janelle Jenstad, Departmental Member (Department of English) Dr. Michael Best, Departmental Member (Department of English) Dr. Annalee Lepp, Outside Member (Department of Women’s Studies) iii Supervisory Committee Dr. Sheila M. Rabillard, Supervisor (Department of English) Dr. Janelle Jenstad, Departmental Member (Department of English) Dr. Michael Best, Departmental Member (Department of English) Dr. Annalee Lepp, Outside Member (Department of Women’s Studies) Abstract The temptation to meddle with Shakespeare has proven irresistible to playwrights since the Restoration and has inspired some of the most reviled and most respected works of theatre. Nahum Tate’s tragic-comic King Lear (1681) was described as an execrable piece of dementation, but played on London stages for one hundred and fifty years. David Garrick was equally tempted to adapt King Lear in the eighteenth century, as were the burlesque playwrights of the nineteenth. In the twentieth century, the meddling continued with works like King Lear’s Wife (1913) by Gordon Bottomley and Dead Letters (1910) by Maurice Baring. -

"I Could Not Say 'Amen'": Prayer and Providence in Macbeth Robert S

CHAPTER 4 "I Could Not Say 'Amen'": Prayer and Providence in Macbeth Robert S. Miola Though ancient playwrights believed in different deities and ethical sys- tems, they too depicted human beings struggling with the gods, with fate and free will, crime and punishment, guilt and suffering. Sophocles (5th c. BC) portrays Oedipus, solver of the Sphinx's riddle and King of Thebes, who discovers that all along he has been fulfilling, not fleeing, the curse of Apollo and its dread predictions: "Lead me away, O friends, the utterly lost (ton meg' olethrion), most accursed (ton kataratotaton), and the one among mortals most hated (exthrotaton) by the gods!" (1341-43). In several plays that provided models for Macbeth, Seneca (d. 65 AD) presents men and women saying the unsayable, doing the unthinkable and suffering the unimaginable. The witch Medea slays her own children in a horrifying act of revenge. In contrast to Euripides Medea, which ends in a choral affirmation of Zeus's justice and order, Seneca's play concludes with Medea's transformation into something inhuman: she leaves the scene of desolation in a chariot drawn by drag- ons, bearing witness, wherever she goes, that there are gods, testare nullos esse, qua veheris, deos (1027). Driven mad by the goddess Juno, Seneca's Hercules in Hercules Furens kills his children, then awakens to full recognition of his deed in suicidal grief and remorse. These tragic heroes struggle against the gods and themselves. Such classical archetypes inform tragedy in the West, with Seneca especially shaping Elizabethan tragedy. Medea and Hercules Furens partly account for the child-killing so prominent in Macbeth. -

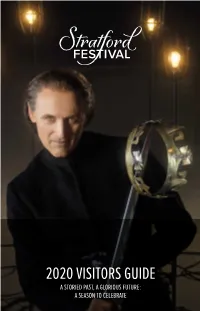

2020 Visitors Guide a Storied Past, a Glorious Future: a Season to Celebrate the Elixir of Power

2020 VISITORS GUIDE A STORIED PAST, A GLORIOUS FUTURE: A SEASON TO CELEBRATE THE ELIXIR OF POWER Irresistible – that’s the only way to describe the variety, quality and excitement that make up the Stratford Festival’s 2020 season. First, there is our stunning new Tom Patterson Theatre, with ravishingly beautiful public spaces and gardens. Its halls, bars and café will be filled throughout the season with music, comedy nights, panel discussions and outstanding speakers to make our Festival even more festive. In the wake of an election in Canada, and in anticipation of one in the U.S., our season explores the theme of Power. Recent years have seen a growing acceptance of the naked use of power. Brute force is in vogue on the world stage, from international trade to immigration and the arms race – and, closer to home, in elections, in the workplace and even in social media engagements. Through comedy, tragedy, song, dance and farce, the plays and musicals of our 2020 season explore the dynamics of power in society, politics, art, gender and family life. In our new Tom Patterson Theatre, we present the two plays that launched the Stratford adventure in 1953: All’s Well That Ends Well and Richard III. The new venue is also home to a new musical, Here’s What It Takes; a new movement-based creation, Frankenstein Revived; and a series of improvisational performances – each one unique and unrepeatable – called An Undiscovered Shakespeare. But the fun isn’t all confined to one theatre. Our historic Festival Theatre showcases two of Shakespeare’s greatest plays, Much Ado About Nothing and Hamlet, as well as Molière’s brilliant satire The Miser and the first major new production in decades of the mischievous musical Chicago. -

Macbeth in World Cinema: Selected Film and Tv Adaptations

International Journal of English and Literature (IJEL) ISSN 2249-6912 Vol. 3, Issue 1, Mar 2013, 179-188 © TJPRC Pvt. Ltd. MACBETH IN WORLD CINEMA: SELECTED FILM AND TV ADAPTATIONS RITU MOHAN 1 & MAHESH KUMAR ARORA 2 1Ph.D. Scholar, Department of Management and Humanities, Sant Longowal Institute of Engineering and Technology, Longowal, Punjab, India 2Associate Professor, Department of Management and Humanities, Sant Longowal Institute of Engineering and Technology, Longowal, Punjab, India ABSTRACT In the rich history of Shakespearean translation/transcreation/appropriation in world, Macbeth occupies an important place. Macbeth has found a long and productive life on Celluloid. The themes of this Bard’s play work in almost any genre, in any decade of any generation, and will continue to find their home on stage, in film, literature, and beyond. Macbeth can well be said to be one of Shakespeare’s most performed play and has enchanted theatre personalities and film makers. Much like other Shakespearean works, it holds within itself the most valuable quality of timelessness and volatility because of which the play can be reproduced in any regional background and also in any period of time. More than the localization of plot and character, it is in the cinematic visualization of Shakespeare’s imagery that a creative coalescence of the Shakespearean, along with the ‘local’ occurs. The present paper seeks to offer some notable (it is too difficult to document and discuss all) adaptations of Macbeth . The focus would be to provide introductory information- name of the film, country, language, year of release, the director, star-cast and the critical reception of the adaptation among audiences. -

2019 Fall Catalogue

PLAYWRIGHTS CANADA PRESS fall 2019 ORDERING AND DISTRIBUTION IN CANADA SALES Canadian Manda Group 664 Annette Street, Toronto, ON M6S 2C8 t: 416.516.0911 | f: 416.516.0917 | e: [email protected] | w: www.mandagroup.com customer service & orders Ryan Muscat, Account Manager, Ontario & Manitoba t: 1.855.626.3222 | f: 1.888.563.8327 | e: [email protected] t: 416.516.0911 x243 Chris Hickey, Sales Manager Iolanda Millar, Account Manager, British Columbia, t: 416.516.0911 x229 Yukon & Northern Territories :: t: 604.662.3511 x246 Tim Gain, National Account Manager, Library Market Nikki Turner, Account Manager, Trade & Library t: 416.516.0911 x231 Market :: t: 416.516.0911 x225 Dave Nadalin, Account Manager, Ontario Anthony Iantorno, National Account Manager, Online t: 416.516.0911 x400 Retailers :: t: 416.516.0911 x242 Jean Cichon, Account Manager, Alberta, Saskatchewan Joanne Adams, National Account Manager, & Manitoba :: t: 403.202.0922 x245 Mass Market :: t: 416.516.0911 x224 Kristina Koski, Account Manager, Special Markets Jacques Filippi, Account Manager, Quebec & Atlantic t: 416.516.0911 x234 Provinces :: t: 1.855.626.3222 x244 David Farag, National Account Coordinator Kate Condon-Moriarty, Account Manager, British t: 416.516.0911 x248 Columbia :: t: 604.662.3511 x247 Emily Patry, Marketing & Communications Manager Caitrin Pilkington, Account Manager, t: 416.516.0911 x230 Special Markets :: t: 416.516.0911 x228 Ellen Warwick, National Account Manager, Special Markets :: t: 416.516.0911 x240 DISTRIBUTION University of Toronto Press Inc. 5201 Dufferin Street, Toronto, ON M3H 5T8 t: 1.800.565.9523 or 416.667.7791 | f: 1.800.221.9985 or 416.667.7832 | e: [email protected] To order by EDI: Through Pubnet: SAN 115 1134 All orders from individuals must be prepaid.