The Coming of the White Bearded Men: the Origin and Development of Thor Heyerdahl's Kon-Tiki Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

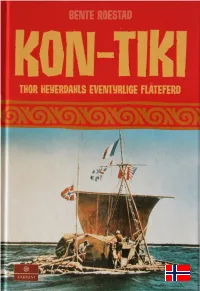

KON-TIKI Thor Heyerdahls Eventyrlige Flåteferd

beNTe rOesTad KON-TIKI ThOr heyerdahls eveNTyrlIge flåTeferd cappelen damm faktum 1 INNhOld 6 fOrOrd 8 OppdagereN ThOr 13 TIlbaKe TIl NaTureN 19 hIsTOrIeN Om TIKI 22 ThOr heyerdahls TeOrI 24 møTTe mOTsTaNd 26 fOrberedelseNe 34 KON-TIKI-flåTeN 42 uTe på haveT 45 haveT på NærT hOld © 2012 CAPPELEN DAMM AS 48 møTe med hvalhaIeN © 2002 N.W. DAMM & SØN AS ISBN 978-82-02-39325-0 52 maNN Over bOrd 2. utgave, 1. opplag 2012 Omslag- og bokdesign: Ingrid Skjæraasen 56 laNd I sIKTe! Trykk og innbinding: Livonia Print, Latvia 2012 Materialet i denne publikasjonen er omfattet av åndsverklovens bestemmelser. Uten særskilt avtale med Cappelen Damm AS er enhver eksemplarfremstilling og 61 måleT var Nådd tilgjengeliggjøring bare tillatt i den utstrekning det er hjemlet i lov eller tillatt gjennom avtale med Kopinor, interesseorgan for rettighetshavere til åndsverk. Utnyttelse i strid med lov eller avtale kan medføre erstatningsansvar 65 KON-TIKI-museeT og inndragning, og kan straffes med bøter eller fengsel. www.cappelendamm.no 68 OrdfOrKlarINger 3 INNhOld 6 fOrOrd 8 OppdagereN ThOr 13 TIlbaKe TIl NaTureN 19 hIsTOrIeN Om TIKI 22 ThOr heyerdahls TeOrI 24 møTTe mOTsTaNd 26 fOrberedelseNe 34 KON-TIKI-flåTeN 42 uTe på haveT 45 haveT på NærT hOld © 2012 CAPPELEN DAMM AS 48 møTe med hvalhaIeN © 2002 N.W. DAMM & SØN AS ISBN 978-82-02-39325-0 52 maNN Over bOrd 2. utgave, 1. opplag 2012 Omslag- og bokdesign: Ingrid Skjæraasen 56 laNd I sIKTe! Trykk og innbinding: Livonia Print, Latvia 2012 Materialet i denne publikasjonen er omfattet av åndsverklovens bestemmelser. Uten særskilt avtale med Cappelen Damm AS er enhver eksemplarfremstilling og 61 måleT var Nådd tilgjengeliggjøring bare tillatt i den utstrekning det er hjemlet i lov eller tillatt gjennom avtale med Kopinor, interesseorgan for rettighetshavere til åndsverk. -

Human Discovery and Settlement of the Remote Easter Island (SE Pacific)

quaternary Review Human Discovery and Settlement of the Remote Easter Island (SE Pacific) Valentí Rull Laboratory of Paleoecology, Institute of Earth Sciences Jaume Almera (ICTJA-CSIC), C. Solé i Sabarís s/n, 08028 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] Received: 19 March 2019; Accepted: 27 March 2019; Published: 2 April 2019 Abstract: The discovery and settlement of the tiny and remote Easter Island (Rapa Nui) has been a classical controversy for decades. Present-day aboriginal people and their culture are undoubtedly of Polynesian origin, but it has been debated whether Native Americans discovered the island before the Polynesian settlement. Until recently, the paradigm was that Easter Island was discovered and settled just once by Polynesians in their millennial-scale eastward migration across the Pacific. However, the evidence for cultivation and consumption of an American plant—the sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas)—on the island before the European contact (1722 CE), even prior to the Europe-America contact (1492 CE), revived controversy. This paper reviews the classical archaeological, ethnological and paleoecological literature on the subject and summarizes the information into four main hypotheses to explain the sweet potato enigma: the long-distance dispersal hypothesis, the back-and-forth hypothesis, the Heyerdahl hypothesis, and the newcomers hypothesis. These hypotheses are evaluated in light of the more recent evidence (last decade), including molecular DNA phylogeny and phylogeography of humans and associated plants and animals, physical anthropology (craniometry and dietary analysis), and new paleoecological findings. It is concluded that, with the available evidence, none of the former hypotheses may be rejected and, therefore, all possibilities remain open. -

Statement by Author

Maya Wetlands: Ecology and Pre-Hispanic Utilization of Wetlands in Northwestern Belize Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Baker, Jeffrey Lee Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 10:39:16 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/237812 MAYA WETLANDS ECOLOGY AND PRE-HISPANIC UTILIZATION OF WETLANDS IN NORTHWESTERN BELIZE by Jeffrey Lee Baker _______________________ Copyright © Jeffrey Lee Baker 2003 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of Anthropology In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College The University of Arizona 2 0 0 3 2 3 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This endeavor would not have been possible with the assistance and advice of a number of individuals. My committee members, Pat Culbert, John Olsen and Owen Davis, who took the time to read and comment on this work Vernon Scarborough and Tom Guderjan also commented on this dissertation and provided additional support during the work. Vernon Scarborough invited me to northwestern Belize to assist in his work examining water management practices at La Milpa. An offer that ultimately led to the current dissertation. Without Tom Guderjan’s offer to work at Blue Creek in 1996, it is unlikely that I would ever have completed my dissertation, and it is possible that I might no longer be in archaeology, a decision I would have deeply regretted. -

Alfred Kidder II in the Development of American Archaeology: a Biographical and Contextual View Karen L

Andean Past Volume 7 Article 14 2005 Alfred Kidder II in the Development of American Archaeology: A Biographical and Contextual View Karen L. Mohr Chavez deceased Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/andean_past Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Mohr Chavez, Karen L. (2005) "Alfred Kidder II in the Development of American Archaeology: A Biographical and Contextual View," Andean Past: Vol. 7 , Article 14. Available at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/andean_past/vol7/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Andean Past by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALFRED KIDDER II IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF AMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY: A BIOGRAPHICAL AND CONTEXTUAL VIEW KAREN L. MOHR CHÁVEZ late of Central Michigan University (died August 25, 2001) Dedicated with love to my parents, Clifford F. L. Mohr and Grace R. Mohr, and to my mother-in-law, Martha Farfán de Chávez, and to the memory of my father-in-law, Manuel Chávez Ballón. INTRODUCTORY NOTE BY SERGIO J. CHÁVEZ1 corroborate crucial information with Karen’s notes and Kidder’s archive. Karen’s initial motivation to write this biography stemmed from the fact that she was one of Alfred INTRODUCTION Kidder II’s closest students at the University of Pennsylvania. He served as her main M.A. thesis This article is a biography of archaeologist Alfred and Ph.D. dissertation advisor and provided all Kidder II (1911-1984; Figure 1), a prominent necessary assistance, support, and guidance. -

Volume 29, Issue 2

History of Anthropology Newsletter Volume 29 Issue 2 December 2002 Article 1 January 2002 Volume 29, Issue 2 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/han Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation (2002) "Volume 29, Issue 2," History of Anthropology Newsletter: Vol. 29 : Iss. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/han/vol29/iss2/1 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/han/vol29/iss2/1 For more information, please contact [email protected]. H istory of A' nthropology N ewsletter XXIX:2 2002 History of Anthropology Newsletter VOLUME XXIX, NUMBER 2 DECEMBER 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS CLIO'S FANCY: DOCUMENTS TO PIQUE THE IDSTORICAL IMAGINATION British Colonialists, Ibo Traders. and Idoma Democrats: A Marxist Anthropologist Enters "The Field" in Nigeria, 1950-51 ..•.•... 3 SOURCES FOR THE IDSTORY OF ANTHROPOLOGY .....•.....•..•.....12 RESEARCH IN PROGRESS ..•••.•.•..•...••.•.•...•..•....•....•..... 12 BI6LIOGRAPIDCA ARCANA L American Anthropologist Special Centennial Issue . • . 13 ll. Recent Dissertations .......................................... 13 IlL Recent Work by Subscribers .•••....•..........•..••......•.. 13 ill. Suggested by Our Readers .••..•••........••.•.• o ••••• o ••••••• 15 The Editorial Committee Robert Bieder Regna Darnell Indiana University University of Western Ontario Curtis Hinsley Dell Hymes Northern Arizona University University of Virginia George W. Stocking William Sturtevant University of Chicago Smithsonian Institution Subscription rates (Each volume contains two numbers: June and December) Individual subscribers (North America) $6.00 Student subscribers 4.00 Institutional subscribers 8.00 Subscribers outside North America 8.00 Checks for renewals, new subscriptions or back numbers should be made payable (in United States dollars only) to: History of Anthropology Newsletter (or to HAN). -

Curren T Anthropology

Forthcoming Current Anthropology Wenner-Gren Symposium Curren Supplementary Issues (in order of appearance) t Human Biology and the Origins of Homo. Susan Antón and Leslie C. Aiello, Anthropolog Current eds. e Anthropology of Potentiality: Exploring the Productivity of the Undened and Its Interplay with Notions of Humanness in New Medical Anthropology Practices. Karen-Sue Taussig and Klaus Hoeyer, eds. y THE WENNER-GREN SYMPOSIUM SERIES Previously Published Supplementary Issues April THE BIOLOGICAL ANTHROPOLOGY OF LIVING HUMAN Working Memory: Beyond Language and Symbolism. omas Wynn and 2 POPULATIONS: WORLD HISTORIES, NATIONAL STYLES, 01 Frederick L. Coolidge, eds. 2 AND INTERNATIONAL NETWORKS Engaged Anthropology: Diversity and Dilemmas. Setha M. Low and Sally GUEST EDITORS: SUSAN LINDEE AND RICARDO VENTURA SANTOS Engle Merry, eds. V The Biological Anthropology of Living Human Populations olum Corporate Lives: New Perspectives on the Social Life of the Corporate Form. Contexts and Trajectories of Physical Anthropology in Brazil Damani Partridge, Marina Welker, and Rebecca Hardin, eds. e Birth of Physical Anthropology in Late Imperial Portugal 5 Norwegian Physical Anthropology and a Nordic Master Race T. Douglas Price and Ofer 3 e Origins of Agriculture: New Data, New Ideas. The Ainu and the Search for the Origins of the Japanese Bar-Yosef, eds. Isolates and Crosses in Human Population Genetics Supplement Practicing Anthropology in the French Colonial Empire, 1880–1960 Physical Anthropology in the Colonial Laboratories of the United States Humanizing Evolution Human Population Biology in the Second Half of the Twentieth Century Internationalizing Physical Anthropology 5 Biological Anthropology at the Southern Tip of Africa The Origins of Anthropological Genetics Current Anthropology is sponsored by e Beyond the Cephalic Index Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Anthropology and Personal Genomics Research, a foundation endowed for scientific, Biohistorical Narratives of Racial Difference in the American Negro educational, and charitable purposes. -

Rongorongo and the Rock Art of Easter Island Shawn Mclaughlin

Rapa Nui Journal: Journal of the Easter Island Foundation Volume 18 Article 2 Issue 2 October 2004 Rongorongo and the Rock Art of Easter Island Shawn McLaughlin Follow this and additional works at: https://kahualike.manoa.hawaii.edu/rnj Part of the History of the Pacific slI ands Commons, and the Pacific slI ands Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation McLaughlin, Shawn (2004) "Rongorongo and the Rock Art of Easter Island," Rapa Nui Journal: Journal of the Easter Island Foundation: Vol. 18 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://kahualike.manoa.hawaii.edu/rnj/vol18/iss2/2 This Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Hawai`i Press at Kahualike. It has been accepted for inclusion in Rapa Nui Journal: Journal of the Easter Island Foundation by an authorized editor of Kahualike. For more information, please contact [email protected]. McLaughlin: Rongorongo and the Rock Art of Easter Island f\2-0M TH£ £DITO{l.~ th 1!J! THIS ISSUE IS MAKING its appearance as the VI Inter- memories of wonderful feasts with wonderful friends. The national Conference on Easter Island and the Pacific, held this tradition of umu feasting is an interesting social phenomena as year in Chile, is ending. We plan to have news about the well as a delicious meal. While many umu are small family meetings and the papers presented in our next issue. A great affairs, at times an umu is prepared to feed the entire island deal of planning and effort went into making the VI1h Interna population. -

Filmpädagogisches Begleitmaterial Für Unterricht Und

FILMPÄDAGOGISCHES BEGLEITMATERIAL FÜR UNTERRICHT UND AuSSERSCHULISCHE BILDUNGSARBEIT Liebe Filmfreunde und Filminteressierte, das vorliegende filmpädagogische Material möchte eine weitergehende Beschäftigung mit dem Film »Kon-Tiki« anregen und begleiten – idealerweise nach einem Besuch im Kino. Die Reihenfolge der inhaltlichen Abschnitte muss dabei nicht eingehalten werden; je nach eigenen Interessen und Kenntnisstand können sie auch übersprungen oder in anderer Rei- henfolge gelesen bzw. zur Bearbeitung herangezogen werden. Im Internet stehen ergänzend viele interessante Videoausschnitte mit Interviews und Hin- tergrundinformationen zum Filmdreh sowie als besondere Anregung für eine kreative Projektarbeit der Plan für den Bau eines Modellfloßes bereit – schauen Sie mal rein unter www.kontiki-derfilm.de/schulfloss. Filmspezifische Fachbegriffe, soweit nicht kurz im Text erläutert, können leicht in entspre- chenden Fachbüchern oder online recherchiert werden, entsprechende Hinweise finden sich am Ende des Materials. Und jetzt: Viel Spaß! 2 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Einführende Informationen 1 Credits 2 Inhalt 3 Figuren 4 Problemstellungen 5 Filmsprache 6 Exemplarische Sequenzanalyse Aufgaben und Unterrichtsvorschläge 7 Fragen und Diskussionsanreize 8 Arbeitsvorschläge (Kopiervorlage) 9 Übersicht: Weiterführende Unterrichtsvorschläge Ergänzende Materialien 10 Sequenzprotokoll 11 Kurzbiografie Thor Heyerdahl 12 Die reale Fahrt der Kon-Tiki im Kontext der Besiedlungstheorien 13 Interview mit Olav Heyerdahl 14 Produktionsnotizen 15 Literaturhinweise -

Testing Traditional Land Divisions on Rapa Nui

Martinsson-Wallin and Wallin: Studies in Global Archaeology no. 20 SPATIAL PERSPECTIVES ON CEREMONIAL COMPLEXES: TESTING TRADITIONAL LAND DIVISIONS ON RAPA NUI Helene Martinsson-Wallin and Paul Wallin Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Uppsala University, Campus Gotland, Sweden [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: The ceremonial sites of Rapa Nui, the ahu, are complex structures that incorporate and display a variety of distinctions and social relationships tied to different land areas that belonged to senior and junior groups. Such distinctions will be analysed via a Correspondence Analysis using selected ahu structures and connected variables. A detailed case study of two ahu in the La Perouse area will focus on the organisation of the variety of prehistoric material expressions connected to these. The aim is to show how habitus works in a local context at the individual organizational level. Through these studies we highlight the complex relationships involved in creating a milieu, in which actors of different groups carry out their practices when creating monuments and organising place. INTRODUCTION Rapa Nui, also known as Easter Island, is geographically the most isolated island in the world (Figure 1). Yet it was found and populated by Polynesian seafarers in prehistoric times (Martinsson-Wallin and Crockford 2002: 256). Prior to archaeological investigations there were several ideas, generally based on genealogies, about when and by whom the island was originally settled. Since there are several versions of genealogical accounts, and their chronological reliability is uncertain, these traditions are difficult to use when discussing temporal issues (Martinsson-Wallin 1994: 76). -

Fay-Cooper Cole, 1881-1961 Author(S): Fred Eggan Reviewed Work(S): Source: American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol

Fay-Cooper Cole, 1881-1961 Author(s): Fred Eggan Reviewed work(s): Source: American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 65, No. 3, Part 1 (Jun., 1963), pp. 641-648 Published by: Blackwell Publishing on behalf of the American Anthropological Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/667373 . Accessed: 08/12/2011 13:11 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Blackwell Publishing and American Anthropological Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Anthropologist. http://www.jstor.org FAY-COOPER COLE 1881-1961 W ITH THE DEATH of Fay-Cooper Cole in Santa Barbara September 3, 1961, the anthropological profession has lost another one of its major figures. He was not only a world authority on the peoples and cultures of Malaysia, and one of the founders of modern archeology, but also a great administrator and developer of men and institutions and a warm and friendly human being. During his long career, which spanned more than half a century, he was in addition one of our foremost interpreters of anthropology to the general public, an activity which he continued after his retirement from the chairmanship of the Department of Anthropology at the University of Chicago in 1947. -

Una Voce JOURNAL of the PAPUA NEW GUINEA ASSOCIATION of AUSTRALIA INC (Formerly the Retired Officers Association of Papua New Guinea Inc)

ISSN 1442-6161, PPA 224987/00025 2005, No 2 - June Una Voce JOURNAL OF THE PAPUA NEW GUINEA ASSOCIATION OF AUSTRALIA INC (formerly the Retired Officers Association of Papua New Guinea Inc) Patrons: His Excellency Major General Michael Jeffery AC CVO MC (Retd) Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia Mrs Roma Bates; Mr Fred Kaad OBE In This Issue CHRISTMAS LUNCHEON – IN 100 WORDS OR LESS 3 This year’s Christmas Luncheon will WALK INTO PARADISE 4 be on Sunday 4 December at the NEWS FROM THE NORTHERN TERRITORY 5 Mandarin Club Sydney. We will have NEWS FROM SOUTH AUSTRALIA 6 a special theme to celebrate 30 years since PNG Independence. Look in the PNG......IN THE NEWS 7 September issue of Una Voce for Rick Nehmy reports 9 details...you will need to book early! More About Tsunami And Earthquakes 11 DONATION OF TIMBER TO MANAM ISLANDERS 14 * * * MADANG HONOURS WAR DEAD 14 VISIT TO THE MOUNTAINS EDUCATIONAL LEADERSHIP 15 The annual spring visit to the Blue MARITIME COLLEGE ACQUIRES STOREHOUSES Mountains will be on Thursday 13 15 October, 2005. Last year we were again KIAPHAT OF PORONPOSOM 16 welcomed at the spacious home of COX AND THE WENZELS 19 George and Edna Oakes at Woodford for THE SOUTH PACIFIC GAMES 20 another warm and friendly gathering. WANPELA MO BLADI ROT NA PINIS OLGERA 22 Fortunately Edna and George will be our Agricultural Development in PNG 24 hosts again this year. Full details in KOKODA TRACK AUTHORITY 26 September issue. REUNIONS 27 * * * Help Wanted 28 CPI: The CPI for our superannuation PNGAA COLLECTION - FRYER LIBRARY 29 rose 1.4% for the six months to March BOOK NEWS AND REVIEWS 30 2005 and will be paid at the end of The Lost Garrison of Rabaul 32 June. -

Download the 2019 Abstract Book

2019 History of Science Society ABSTRACT BOOK UTRECHT, THE NETHERLANDS | 23-27 JULY 2019 History of Science Society | Abstract Book | Utrecht 2019 1 "A Place for Human Inquiry": Leibniz and Christian Wolff against Lomonosov’s Mineral Science the attacks of French philosophes in Anna Graber the wake of the Great Lisbon Program in the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine, University of Earthquake of 1755. This paper Minnesota concludes by situating Lomonosov While polymath and first Russian in a ‘mining Enlightenment’ that member of the St. Petersburg engrossed major thinkers, Academy of Sciences Mikhail bureaucrats, and mining Lomonosov’s research interests practitioners in Central and Northern were famously broad, he began and Europe as well as Russia. ended his career as a mineral Aspects of Scientific Practice/Organization | scientist. After initial study and Global or Multilocational | 18th century work in mining science and "Atomic Spaghetti": Nuclear mineralogy, he dropped the subject, Energy and Agriculture in Italy, returning to it only 15 years later 1950s-1970s with a radically new approach. This Francesco Cassata paper asks why Lomonosov went University of Genoa (Italy) back to the subject and why his The presentation will focus on the approach to the mineral realm mutagenesis program in agriculture changed. It argues that he returned implemented by the Italian Atomic to the subject in answer to the needs Energy Commission (CNRN- of the Russian court for native CNEN), starting from 1956, through mining experts, but also, and more the establishment of a specific significantly, because from 1757 to technological and experimental his death in 1765 Lomonosov found system: the so-called “gamma field”, in mineral science an opportunity to a piece of agricultural land with a engage in some of the major debates radioisotope of Cobalt-60 at the of the Enlightenment.