Studia Hercynia 2018-1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regional Case Study of Pazardzhik Province, Bulgaria

Regional Case Study of Pazardzhik Province, Bulgaria ESPON Seminar "Territorial Cohesion Post 2020: Integrated Territorial Development for Better Policies“ Sofia, Bulgaria, 30th of May 2018 General description of the Region - Located in the South-central part of Bulgaria - Total area of the region: 4,458 km2. - About 56% of the total area is covered by forests; 36% - agricultural lands - Population: 263,630 people - In terms of population: Pazardzhik municipality is the largest one with 110,320 citizens General description of the Region - 12 municipalities – until 2015 they were 11, but as of the 1st of Jan 2015 – a new municipality was established Total Male Female Pazardzhik Province 263630 129319 134311 Batak 5616 2791 2825 Belovo 8187 3997 4190 Bratsigovo 9037 4462 4575 Velingrad 34511 16630 17881 Lesichovo 5456 2698 2758 Pazardzhik 110302 54027 56275 Panagyurishte 23455 11566 11889 Peshtera 18338 8954 9384 Rakitovo 14706 7283 7423 Septemvri 24511 12231 12280 Strelcha 4691 2260 2431 Sarnitsa 4820 2420 2400 General description of the Region Population: negative trends 320000 310000 300000 290000 280000 Pazardzhik Province 270000 Population 260000 250000 240000 230000 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 There is a steady trend of reducing the population of the region in past 15 years. It has dropped down by 16% in last 15 years, with an average for the country – 12.2%. The main reason for that negative trend is the migration of young and medium aged people to West Europe, the U.S. and Sofia (capital and the largest city in Bulgaria). -

Annex REPORT for 2019 UNDER the “HEALTH CARE” PRIORITY of the NATIONAL ROMA INTEGRATION STRATEGY of the REPUBLIC of BULGAR

Annex REPORT FOR 2019 UNDER THE “HEALTH CARE” PRIORITY of the NATIONAL ROMA INTEGRATION STRATEGY OF THE REPUBLIC OF BULGARIA 2012 - 2020 Operational objective: A national monitoring progress report has been prepared for implementation of Measure 1.1.2. “Performing obstetric and gynaecological examinations with mobile offices in settlements with compact Roma population”. During the period 01.07—20.11.2019, a total of 2,261 prophylactic medical examinations were carried out with the four mobile gynaecological offices to uninsured persons of Roma origin and to persons with difficult access to medical facilities, as 951 women were diagnosed with diseases. The implementation of the activity for each Regional Health Inspectorate is in accordance with an order of the Minister of Health to carry out not less than 500 examinations with each mobile gynaecological office. Financial resources of BGN 12,500 were allocated for each mobile unit, totalling BGN 50,000 for the four units. During the reporting period, the mobile gynecological offices were divided into four areas: Varna (the city of Varna, the village of Kamenar, the town of Ignatievo, the village of Staro Oryahovo, the village of Sindel, the village of Dubravino, the town of Provadia, the town of Devnya, the town of Suvorovo, the village of Chernevo, the town of Valchi Dol); Silistra (Tutrakan Municipality– the town of Tutrakan, the village of Tsar Samuel, the village of Nova Cherna, the village of Staro Selo, the village of Belitsa, the village of Preslavtsi, the village of Tarnovtsi, -

1 I. ANNEXES 1 Annex 6. Map and List of Rural Municipalities in Bulgaria

I. ANNEXES 1 Annex 6. Map and list of rural municipalities in Bulgaria (according to statistical definition). 1 List of rural municipalities in Bulgaria District District District District District District /Municipality /Municipality /Municipality /Municipality /Municipality /Municipality Blagoevgrad Vidin Lovech Plovdiv Smolyan Targovishte Bansko Belogradchik Apriltsi Brezovo Banite Antonovo Belitsa Boynitsa Letnitsa Kaloyanovo Borino Omurtag Gotse Delchev Bregovo Lukovit Karlovo Devin Opaka Garmen Gramada Teteven Krichim Dospat Popovo Kresna Dimovo Troyan Kuklen Zlatograd Haskovo Petrich Kula Ugarchin Laki Madan Ivaylovgrad Razlog Makresh Yablanitsa Maritsa Nedelino Lyubimets Sandanski Novo Selo Montana Perushtitsa Rudozem Madzharovo Satovcha Ruzhintsi Berkovitsa Parvomay Chepelare Mineralni bani Simitli Chuprene Boychinovtsi Rakovski Sofia - district Svilengrad Strumyani Vratsa Brusartsi Rodopi Anton Simeonovgrad Hadzhidimovo Borovan Varshets Sadovo Bozhurishte Stambolovo Yakoruda Byala Slatina Valchedram Sopot Botevgrad Topolovgrad Burgas Knezha Georgi Damyanovo Stamboliyski Godech Harmanli Aitos Kozloduy Lom Saedinenie Gorna Malina Shumen Kameno Krivodol Medkovets Hisarya Dolna banya Veliki Preslav Karnobat Mezdra Chiprovtsi Razgrad Dragoman Venets Malko Tarnovo Mizia Yakimovo Zavet Elin Pelin Varbitsa Nesebar Oryahovo Pazardzhik Isperih Etropole Kaolinovo Pomorie Roman Batak Kubrat Zlatitsa Kaspichan Primorsko Hayredin Belovo Loznitsa Ihtiman Nikola Kozlevo Ruen Gabrovo Bratsigovo Samuil Koprivshtitsa Novi Pazar Sozopol Dryanovo -

Appendix 1 D Municipalities and Mountainous

National Agriculture and Rural Development Plan 2000-2006 APPENDIX 1 D MUNICIPALITIES AND MOUNTAINOUS SETTLEMENTS WITH POTENTIAL FOR RURAL TOURISM DEVELOPMENT DISTRICT MUNICIPALITIES MOUNTAINOUS SETTLEMENTS Municipality Settlements* Izgrev, Belo pole, Bistrica, , Buchino, Bylgarchevo, Gabrovo, Gorno Bansko(1), Belitza, Gotze Delchev, Garmen, Kresna, Hyrsovo, Debochica, Delvino, Drenkovo, Dybrava, Elenovo, Klisura, BLAGOEVGRAD Petrich(1), Razlog, Sandanski(1), Satovcha, Simitly, Blagoevgrad Leshko, Lisiia, Marulevo, Moshtanec, Obel, Padesh, Rilci, Selishte, Strumiani, Hadjidimovo, Jacoruda. Logodaj, Cerovo Sungurlare, Sredets, Malko Tarnovo, Tzarevo (4), BOURGAS Primorsko(1), Sozopol(1), Pomorie(1), Nesebar(1), Aitos, Kamenovo, Karnobat, Ruen. Aksakovo, Avren, Biala, Dolni Chiflik, Dalgopol, VARNA Valchi Dol, Beloslav, Suvorovo, Provadia, Vetrino. Belchevci, Boichovci, Voneshta voda, Vyglevci, Goranovci, Doinovci, VELIKO Elena, Zlataritsa, Liaskovets, Pavlikeni, Polski Veliko Dolni Damianovci, Ivanovci, Iovchevci, Kladni dial, Klyshka reka, Lagerite, TARNOVO Trambesh, Strajitsa, Suhindol. Tarnovo Mishemorkov han, Nikiup, Piramidata, Prodanovci, Radkovci, Raikovci, Samsiite, Seimenite, Semkovci, Terziite, Todorovci, Ceperanite, Conkovci Belogradchik, Kula, Chuprene, Boinitsa, Bregovo, VIDIN Gramada, Dimovo, Makresh, Novo Selo, Rujintsi. Mezdra, Krivodol, Borovan, Biala Slatina, Oriahovo, VRATZA Vratza Zgorigrad, Liutadjik, Pavolche, Chelopek Roman, Hairedin. Angelov, Balanite, Bankovci, Bekriite, Bogdanchovci, Bojencite, Boinovci, Boicheta, -

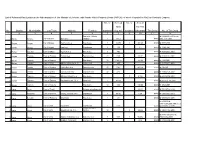

List of Released Real Estates in the Administration of the Ministry Of

List of Released Real Estates in the Administration of the Ministry of Defence, with Private Public Property Deeds (PPPDs), of which Property the MoD is Allowed to Dispose No. of Built-up No. of Area of Area the Plot No. District Municipality City/Town Address Function Buildings (sq. m.) Facilities (decares) Title Deed No. of Title Deed 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Part of the Military № 874/02.05.1997 for the 1 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Slaveykov Hospital 1 545,4 PPPD whole real estate 2 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Kapcheto Area Storehouse 6 623,73 3 29,143 PPPD № 3577/2005 3 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Sarafovo Storehouse 6 439 5,4 PPPD № 2796/2002 4 Burgas Nesebar Town of Obzor Top-Ach Area Storehouse 5 496 PPPD № 4684/26.02.2009 5 Burgas Pomorie Town of Pomorie Honyat Area Barracks area 24 9397 49,97 PPPD № 4636/12.12.2008 6 Burgas Pomorie Town of Pomorie Storehouse 18 1146,75 74,162 PPPD № 1892/2001 7 Burgas Sozopol Town of Atiya Military station, by Bl. 11 Military club 1 240 PPPD № 3778/22.11.2005 8 Burgas Sredets Town of Sredets Velikin Bair Area Barracks area 17 7912 40,124 PPPD № 3761/05 9 Burgas Sredets Town of Debelt Domuz Dere Area Barracks area 32 5785 PPPD № 4490/24.04.2008 10 Burgas Tsarevo Town of Ahtopol Mitrinkovi Kashli Area Storehouse 1 0,184 PPPD № 4469/09.04.2008 11 Burgas Tsarevo Town of Tsarevo Han Asparuh Str., Bl. -

Priority Public Investments for Wastewater Treatment and Landfill of Waste

Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Develonment Europe and Central Asia Region 32051 BULGARIA Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL SEQUENCING STRATEGIES FOR EU ACCESSION PriorityPublic Investments for Wastewater Treatment and Landfill of Waste *t~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Public Disclosure Authorized IC- - ; s - o Fk - L - -. Public Disclosure Authorized The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized May 2004 - "Wo BULGARIA ENVIRONMENTAL SEQUENCING STRATEGIES FOR EU ACCESSION Priority Public Investments for Wastewater Treatment and Landfill of Waste May 2004 Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Development Europe and Central Asia Region Report No. 27770 - BUL Thefindings, interpretationsand conclusions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. Coverphoto is kindly provided by the external communication office of the World Bank County Office in Bulgaria. The report is printed on 30% post consumer recycledpaper. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ..................................................................... i Abbreviations and Acronyms ..................................................................... ii Summary ..................................................................... iiM Introduction.iii Wastewater.iv InstitutionalIssues .xvi Recommendations........... xvii Introduction ...................................................................... 1 Part I: The Strategic Settings for -

Modernization of the Pazardzhik

PROJECT Modernization of the Pazardzhik - Stamboliyski railway section part of the Trans-European railway Completion of construction works on the Project "Modernization of the Pazardzhik - Stamboliyski railway section part of the Trans-European railway network" Funding: National (Bulgaria) Duration: Nov 2013 - Jun 2017 Status: Complete Background & policy context: "Modernization of the Pazardzhik - Stamboliyski railway section from the end of Railway Switch № 5 (km 119+624) on Track № 1 and from the end of Railway Switch № 1 (km 119+692) on Track № 2 at the eastern throat of Pazardzhik Station, to the end of Railway Switch № 3 (km 138+755) on Track № 1 and to the beginning of Railway Switch № 1 (km 138+810) on Track № 2 at the western throat of the Stamboliyski Station, inclusive of both Ognyanovo and Stamboliyski Stations" This is a I (first) category construction according to Art. 137, para. 1, item 1, letters "a" and "b" of the Spatial Planning Act (SPA), and Art. 2, para. 1, item 3 of Regulation № 1 on the nomenclature of the type of constructions, 2003. Location: National Railway network of the Republic of Bulgaria - Septemvri - Plovdiv - Pazardzhik - Stamboliyski railway section, Pazardzhik District, on the territory of Pazardzhik Municipality, and Plovdiv District, on the territory of Stamboliyski Municipality. Completed under Building Permit № RS- 67/20.11.2013, issued by the Ministry of Regional Development and Public Works (MoRDPW) Objectives: Modernisation of the main electrified double railway line designed for a design speed of 160 km/h, and overhead line designed for 200 km/h. (with a tolerance of +10% on these values), subject to the relevant national and European technical regulations, incl. -

Republic of Bulgaria Ministry of Energy 1/73 Fifth

REPUBLIC OF BULGARIA MINISTRY OF ENERGY FIFTH NATIONAL REPORT ON BULGARIA’S PROGRESS IN THE PROMOTION AND USE OF ENERGY FROM RENEWABLE SOURCES Drafted in accordance with Article 22(1) of Directive 2009/28/EC on the promotion of the use of energy from renewable sources on the basis of the model for Member State progress reports set out in Directive 2009/28/EC December 2019 1/73 REPUBLIC OF BULGARIA MINISTRY OF ENERGY TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS USED ..................................................................................................................................4 UNITS OF MEASUREMENT ............................................................................................................................5 1. Shares (sectoral and overall) and actual consumption of energy from renewable sources in the last 2 years (2017 and 2018) (Article 22(1) of Directive 2009/28/EC) ........................................................................6 2. Measures taken in the last 2 years (2017 and 2018) and/or planned at national level to promote the growth of energy from renewable sources, taking into account the indicative trajectory for achieving the national RES targets as outlined in your National Renewable Energy Action Plan. (Article 22(1)(a) of Directive 2009/28/EC) ......................................................................................................................................................... 11 2.a Please describe the support schemes and other measures currently in place that are applied to promote energy from renewable sources and report on any developments in the measures used with respect to those set out in your National Renewable Energy Action Plan (Article 22(1)(b) of Directive 2009/28/EC) ..................... 18 2.b Please describe the measures in ensuring the transmission and distribution of electricity produced from renewable energy sources and in improving the regulatory framework for bearing and sharing of costs related to grid connections and grid reinforcements (for accepting greater loads). -

Territorial Governance in the Western Balkans

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Repository ISTITUZIONALE Annual review of TERRITORIAL GOVERNANCE IN THE WESTERN BALKANS Original Annual review of TERRITORIAL GOVERNANCE IN THE WESTERN BALKANS / Cotella, G.. - In: ANNUAL REVIEW OF TERRITORIAL GOVERNANCE IN THE WESTERN BALKANS. - ISSN 2707-9384. - STAMPA. - 2/2020(2020), pp. 1- 174. Availability: This version is available at: 11583/2858718 since: 2020-12-22T19:12:09Z Publisher: Co-PLAN, Institute for Habitat Development and POLIS Press. Published DOI: Terms of use: openAccess This article is made available under terms and conditions as specified in the corresponding bibliographic description in the repository Publisher copyright (Article begins on next page) 08 October 2021 Annual review of TERRITORIAL GOVERNANCE IN THE WESTERN BALKANS JOURNAL OF THE WESTERN BALKANS NETWORK ON TERRITORIAL GOVERNANCE (TG-WeB) Governance in The eects of COVID-19 on Tourism in the Age Western Balkans Governance and Development of Uncertainty Municipal Finances in Water and Energy Learning from the the Context of COVID-19 for Resilience CENTROPE Initiative ISSUE 2 2020 Annual Review of TERRITORIAL GOVERNANCE IN THE WESTERN BALKANS JOURNAL OF THE WESTERN BALKAN NETWORK ON TERRITORIAL GOVERNANCE (TG-WeB) Annual Review of Territorial Governance in the Western Balkans Journal of Western Balkan Network on Territorial Governance (TG-WeB) Issue 2 December 2020 Print ISSN 2617-7684 Online ISSN 2707-9384 Editor-in-Chief Dr. Rudina Toto Editorial Manager Dr. Ledio Allkja Editorial Board Prof. Dr. Besnik Aliaj Dr. Dritan Shutina Dr. Sotir Dhamo Dr. Peter Nientied Dr. Marjan Nikolov Prof. Dr. Sherif Lushaj Prof. Dr. Giancarlo Cotella Dr. Dragisa Mijacic Language Editor Dr. Maren Larsen Design Klesta Galanxhi Aida Ciro Scope: Annual Review of Territorial Governance in the Western Balkans is a periodical publication with select policy briefs on matters related to territorial governance, sketching the present situation, the Europeanisation process, the policy and the research and development agenda for the near future. -

Modernity and Tradition: European and National in Bulgaria

MODERNITY AND TRADITION: EUROPEAN AND NATIONAL IN BULGARIA Marko Hajdinjak, Maya Kosseva, Antonina Zhelyazkova IMIR MODERNITY AND TRADITION: EUROPEAN AND NATIONAL IN BULGARIA Marko Hajdinjak, Maya Kosseva, Antonina Zhelyazkova Project IME: Identities and Modernities in Europe: European and National Identity Construction Programmes, Politics, Culture, History and Religion International Center for Minority Studies and Intercultural Relations Sofia, 2012 This book is an outcome of the international research project IME – Identities and Modernities in Europe: European and National Identity Construction Programmes, Politics, Culture, History and Religion (2009-2012). IME was coordinated by Dr. Atsuko Ichijo from the Kingston University, UK. It involved Universities and research institutes from Bulgaria, Croatia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Turkey, and the United Kingdom. The project was funded by the Seventh Framework Program of the European Commission (FP7 2007-2013) Theme: SSH-2007-5.2.1 – Histories and Identities: articulating national and European identities Funding scheme: Collaborative projects (small or medium scale focused research projects) Grant agreement no.: 215949 For more information about project IME, visit: http://fass.kingston.ac.uk/research/helen-bamber/ime © Marko Hajdinjak, author, 2012 © Maya Kosseva, author, 2012 © Antonina Zhelyazkova, author, 2012 © International Center for Minority Studies and Intercultural Relations, 2012 ISBN: 978-954-8872-70-6 CONTENTS Introduction, Marko Hajdinjak .......................7 Catching Up with the Uncatchable: European Dilemmas and Identity Construction on Bulgarian Path to Modernity, Maya Kosseva, Antonina Zhelyazkova, Marko Hajdinjak ..........13 Identity Construction through Education, State Promotion and Diaspora Policies in Bulgaria, Antonina Zhelyazkova, Maya Kosseva, Marko Hajdinjak ..........65 Living Next Door to “Europe”: Bulgarian Education between Tradition and Modernity, and between the European and National, Maya Kosseva, Marko Hajdinjak .................... -

Abdera, 75, 93, 127, 218, 242, 274 Abydos, 91, 94, 102, 106, 108

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-03053-4 - Athens, Thrace, and the Shaping of Athenian Leadership Matthew A. Sears Index More information INDEX Abdera, 75, 93, 127, 218, 242, 274 Agora (at Athens), 81, 239 Abydos, 91, 94, 102, 106, 108, 122, 125, Agyrrhius, 121 164, 281 Ajax, 61 Acharnae, 267, 269 Alcibiades, 22, 31, 42, 76, 82, 85, 137, 138, Acharnians (play of Aristophanes), 161, 163 12, 17, 146, 200, 213, 250, 261, fall out of favor at Athens, 96–97 262, 309 his campaigns in Thrace during the Acoris (Egyptian king), 38, 39, 129 Peloponnesian War, 94–97, 106–9, Acropolis of Athens, 54 163, 276 Adeimantus, 108, 150 his capture of Selymbria, 22, 23 adventurers, adventurism, 60, 110, 136, 297 his estates in Thrace, 96–97 Aeacus, 61 his horsemanship, 228 Aegina, 61 his many changes in character, 141 Aegospotami, battle of, 34, 35, 36, 90, 91, his many changes of allegiance, 90 96, 116, 125, 131, 138, 276 his relationship with Thrasybulus, Aenus, 87, 260, 261, 274, 275 91–92 Aeschines, 18, 19, 267, 272, 304 his speech in favor of the Sicilian Aeschylus, 16, 17, 154, 257 Expedition, 226 Aetolia, the Aetolians, 260 his ties to Thrace and other Against Aristocrates (work of Thracophiles, 103–4, 106–9, Demosthenes), 47, 134, 216, 291 155 Against Neaera (work of his usefulness to Athens, 91 pseudo-Demosthenes), 165 and Persia, 37 Agamemnon, 119, 214 as potential tyrant, 5, 176 Agesilaus, 38, 116, 117, 171 and Sparta, 140 in Egypt, 38, 40 Alcmeonids, the, 53, 57 and Xenophon, 110, 117 Alexander I of Macedon, 72 agō. -

Interstate Alliances of the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: a Socio-Cultural Perspective

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 Interstate Alliances of the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: A Socio-Cultural Perspective Nicholas D. Cross The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1479 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INTERSTATE ALLIANCES IN THE FOURTH-CENTURY BCE GREEK WORLD: A SOCIO-CULTURAL PERSPECTIVE by Nicholas D. Cross A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 Nicholas D. Cross All Rights Reserved ii Interstate Alliances in the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: A Socio-Cultural Perspective by Nicholas D. Cross This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________ __________________________________________ Date Jennifer Roberts Chair of Examining Committee ______________ __________________________________________ Date Helena Rosenblatt Executive Officer Supervisory Committee Joel Allen Liv Yarrow THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Interstate Alliances of the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: A Socio-Cultural Perspective by Nicholas D. Cross Adviser: Professor Jennifer Roberts This dissertation offers a reassessment of interstate alliances (συµµαχία) in the fourth-century BCE Greek world from a socio-cultural perspective.