Territorial Governance in the Western Balkans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regional Case Study of Pazardzhik Province, Bulgaria

Regional Case Study of Pazardzhik Province, Bulgaria ESPON Seminar "Territorial Cohesion Post 2020: Integrated Territorial Development for Better Policies“ Sofia, Bulgaria, 30th of May 2018 General description of the Region - Located in the South-central part of Bulgaria - Total area of the region: 4,458 km2. - About 56% of the total area is covered by forests; 36% - agricultural lands - Population: 263,630 people - In terms of population: Pazardzhik municipality is the largest one with 110,320 citizens General description of the Region - 12 municipalities – until 2015 they were 11, but as of the 1st of Jan 2015 – a new municipality was established Total Male Female Pazardzhik Province 263630 129319 134311 Batak 5616 2791 2825 Belovo 8187 3997 4190 Bratsigovo 9037 4462 4575 Velingrad 34511 16630 17881 Lesichovo 5456 2698 2758 Pazardzhik 110302 54027 56275 Panagyurishte 23455 11566 11889 Peshtera 18338 8954 9384 Rakitovo 14706 7283 7423 Septemvri 24511 12231 12280 Strelcha 4691 2260 2431 Sarnitsa 4820 2420 2400 General description of the Region Population: negative trends 320000 310000 300000 290000 280000 Pazardzhik Province 270000 Population 260000 250000 240000 230000 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 There is a steady trend of reducing the population of the region in past 15 years. It has dropped down by 16% in last 15 years, with an average for the country – 12.2%. The main reason for that negative trend is the migration of young and medium aged people to West Europe, the U.S. and Sofia (capital and the largest city in Bulgaria). -

Good Practices in Target Libraries from Plovdiv District

Good Practices in Target Libraries from Plovdiv District 4 September 2011, Plovdiv, Ivan Vazov Public Library LIST OF MEETING PARTICIPANTS No. Name Organization/Institution Settlement 1. Ana Belcheva Municipal administration Rakovski Rakovski 2. Angelina Stavreva Ivan Vazov Public Library, Methodology Dept. Plovdiv 3. Ani Sirakova Library at Sts. Cyril and Methodius PC Parvomay 4. Anka Bekirova Library at Iskra Public Chitalishte Kaloyanovo 5. Apostol Stanev Library at Sokolov Public Chitalishte Panicheri 6. Valya Stoyanova Library at N.Y. Vaptsarov Public Chitalishte Stamboliyski 7. Vasilka Bahchevanska Library at Vasil Kolev Public Chitalishte Trilistnik 8. Vaska Mincheva Library at Probuda Public Chitalishte Krichim 9. Vaska Tonova Ivan Vazov Public Library, Children’s Dept. Plovdiv 10. Velizar Petrov Regional Information Center Plovdiv 11. Vera Endreva Library at Hristo Botev Public Chitalishte Zlatitrap 12. Vera Kirilova NAWV Plovdiv 13. Gergana Vulcheva Library at Ivan Vazov Public Chitalishte Iskra 14. Gyurgena Madzhirova Library at Lyuben Karavelov Public Chitalishte Kurtovo Konare 15. Daniela Kostova Municipal administration Asenovgrad Asenovgrad 16. Darina Markova Library at Hristo Botev Public Chitalishte Dabene 17. Dzhamal Kichukov “Zora” Library Laki 18. Dimitar Minev Ivan Vazov Public Library, Director Plovdiv 19. Dobrinka Batinkova Library at N.Y. Vaptsarov Public Chitalishte Kuklen 20. Donka Kumanova Library at Sts. Cyril and Methodius PC Shishmantsi 21. Elena Atanasova Library at Ivan Vazov Public Chitalishte Plovdiv 22. E lena Batinkova Library at Samorazvitie Public Chitalishte Brestnik 23. Elena Mechkova Library at N.Y. Vaptsarov Public Chitalishte Topolovo 24. Elena Raychinova Library at Ivan Vazov Public Chitalishte Sopot 25. Emilia Angelova Library at Sts. Cyril and Methodius PC Parvomay page 1 No. -

Eski Zağra (Stara Zagora)

T.C. FİLİBE BAŞKONSOLOSLUĞU TİCARET ATAŞELİĞİ ESKİ ZAĞRA (STARA ZAGORA) EYLÜL 2016 T.C. FİLİBE BAŞKONSOLOSLUĞU TİCARET ATAŞELİĞİ İÇİNDEKİLER SAYFA NO: 1. GİRİŞ .................................................................................................................................................... 2 2. ESKİ ZAĞRA (STARA ZAGORA) HAKKINDA GENEL BİLGİLER ....................................... 3 2.1. Bölgenin Ülke Genelindeki Yeri ve Önemi .................................................................................... 3 2.2. Coğrafi Bilgiler ve Su Kaynakları ................................................................................................... 4 2.3. Nüfus .................................................................................................................................................. 7 2.4. Eğitim ................................................................................................................................................ 8 2.5. Eski Zağra’nın İlçeleri .............................................................................................................. 10 2.5.1. Eski Zağra (Stara Zagora) Merkez İlçe .......................................................................... 10 2.5.2. Kazanlık Belediyesi ........................................................................................................... 13 2.5.3. Radnevo ve Gılıbovo İlçeleri ............................................................................................. 18 2.5.4. Çirpan İlçesi ...................................................................................................................... -

Do Public Fund Windfalls Increase Corruption? Evidence from a Natural Disaster Elena Nikolovaa Nikolay Marinovb 68131 Mannheim A5-6, Germany October 5, 2016

Do Public Fund Windfalls Increase Corruption? Evidence from a Natural Disaster Elena Nikolovaa Nikolay Marinovb 68131 Mannheim A5-6, Germany October 5, 2016 Abstract We show that unexpected financial windfalls increase corruption in local govern- ment. Our analysis uses a new data set on flood-related transfers, and the associated spending infringements, which the Bulgarian central government distributed to mu- nicipalities following torrential rains in 2004 and 2005. Using information from the publicly available audit reports we are able to build a unique objective index of cor- ruption. We exploit the quasi-random nature of the rainfall shock (conditional on controls for ground flood risk) to isolate exogenous variation in the amount of funds received by each municipality. Our results imply that a 10 % increase in the per capita amount of disbursed funds leads to a 9.8% increase in corruption. We also present suggestive evidence that more corrupt mayors anticipated punishment by voters and dropped out of the next election race. Our results highlight the governance pitfalls of non-tax transfers, such as disaster relief or assistance from international organizations, even in moderately strong democracies. Keywords: corruption, natural disasters, governance JEL codes: D73, H71, P26 aResearch Fellow, Central European Labour Studies Institute, Slovakia and associated researcher, IOS Regensburg, Germany. Email: [email protected]. We would like to thank Erik Bergl¨of,Rikhil Bhav- nani, Simeon Djankov, Sergei Guriev, Stephan Litschig, Ivan Penkov, Grigore Pop-Eleches, Sandra Sequeira and conference participants at the 2015 Annual Meeting of the European Public Choice Society, Groningen, the 2015 American Political Science Association, San Francisco and seminar participants at Brunel, King's College workshop on corruption, and LSE for useful comments, and Erik Bergl¨ofand Stefka Slavova for help with obtaining Bulgarian rainfall data. -

Annex REPORT for 2019 UNDER the “HEALTH CARE” PRIORITY of the NATIONAL ROMA INTEGRATION STRATEGY of the REPUBLIC of BULGAR

Annex REPORT FOR 2019 UNDER THE “HEALTH CARE” PRIORITY of the NATIONAL ROMA INTEGRATION STRATEGY OF THE REPUBLIC OF BULGARIA 2012 - 2020 Operational objective: A national monitoring progress report has been prepared for implementation of Measure 1.1.2. “Performing obstetric and gynaecological examinations with mobile offices in settlements with compact Roma population”. During the period 01.07—20.11.2019, a total of 2,261 prophylactic medical examinations were carried out with the four mobile gynaecological offices to uninsured persons of Roma origin and to persons with difficult access to medical facilities, as 951 women were diagnosed with diseases. The implementation of the activity for each Regional Health Inspectorate is in accordance with an order of the Minister of Health to carry out not less than 500 examinations with each mobile gynaecological office. Financial resources of BGN 12,500 were allocated for each mobile unit, totalling BGN 50,000 for the four units. During the reporting period, the mobile gynecological offices were divided into four areas: Varna (the city of Varna, the village of Kamenar, the town of Ignatievo, the village of Staro Oryahovo, the village of Sindel, the village of Dubravino, the town of Provadia, the town of Devnya, the town of Suvorovo, the village of Chernevo, the town of Valchi Dol); Silistra (Tutrakan Municipality– the town of Tutrakan, the village of Tsar Samuel, the village of Nova Cherna, the village of Staro Selo, the village of Belitsa, the village of Preslavtsi, the village of Tarnovtsi, -

1 I. ANNEXES 1 Annex 6. Map and List of Rural Municipalities in Bulgaria

I. ANNEXES 1 Annex 6. Map and list of rural municipalities in Bulgaria (according to statistical definition). 1 List of rural municipalities in Bulgaria District District District District District District /Municipality /Municipality /Municipality /Municipality /Municipality /Municipality Blagoevgrad Vidin Lovech Plovdiv Smolyan Targovishte Bansko Belogradchik Apriltsi Brezovo Banite Antonovo Belitsa Boynitsa Letnitsa Kaloyanovo Borino Omurtag Gotse Delchev Bregovo Lukovit Karlovo Devin Opaka Garmen Gramada Teteven Krichim Dospat Popovo Kresna Dimovo Troyan Kuklen Zlatograd Haskovo Petrich Kula Ugarchin Laki Madan Ivaylovgrad Razlog Makresh Yablanitsa Maritsa Nedelino Lyubimets Sandanski Novo Selo Montana Perushtitsa Rudozem Madzharovo Satovcha Ruzhintsi Berkovitsa Parvomay Chepelare Mineralni bani Simitli Chuprene Boychinovtsi Rakovski Sofia - district Svilengrad Strumyani Vratsa Brusartsi Rodopi Anton Simeonovgrad Hadzhidimovo Borovan Varshets Sadovo Bozhurishte Stambolovo Yakoruda Byala Slatina Valchedram Sopot Botevgrad Topolovgrad Burgas Knezha Georgi Damyanovo Stamboliyski Godech Harmanli Aitos Kozloduy Lom Saedinenie Gorna Malina Shumen Kameno Krivodol Medkovets Hisarya Dolna banya Veliki Preslav Karnobat Mezdra Chiprovtsi Razgrad Dragoman Venets Malko Tarnovo Mizia Yakimovo Zavet Elin Pelin Varbitsa Nesebar Oryahovo Pazardzhik Isperih Etropole Kaolinovo Pomorie Roman Batak Kubrat Zlatitsa Kaspichan Primorsko Hayredin Belovo Loznitsa Ihtiman Nikola Kozlevo Ruen Gabrovo Bratsigovo Samuil Koprivshtitsa Novi Pazar Sozopol Dryanovo -

Download a Plovdiv Guide

Map Sightseeing Culture Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Shopping Hotels Plovdiv №01, Autumn 2017 Contents Arriving & Getting Around 3 Plovdiv Basics 5 ESSENTIAL CITY GUIDES History 6 Feature 7 National Revival Architecture GET THE IN YOUR POCKET APP What’s on 8 In Your Pocket City Essentials is available for Android and iOS from Google Play Store and the App Store. Restaurants 10 Featuring more than 45 cities across Europe, In Your Pocket City Essentials is an invaluable resource telling Cafes 14 you about our favourite places, carefully picked by our local editors. All venues are mapped and work offline Nightlife 16 to help you avoid roaming charges while you enjoy the best our cities have to offer. Download In Your Pocket Sightseeing 18 City Essentials now. Shopping 25 Directory 27 Leisure 28 Hotels 30 Map 32 facebook.com/PlovdivInYourPocket 2017 1 Foreword Bulgaria’s second largest city is home to the country’s most impressive man-made sight: the incredibly well preserved Ancient Тheatre sitting in the saddle between two of the 6 (originally 7) hills the city is famed for and providing a breath- taking view of the city and the Rhodope mountain range. Plovdiv boasts plentiful Roman ruins and an enchanting Old Publisher Town of cobbled streets and timber-framed 19th century Inside & out Ltd. painted houses with overhanging oriel windows. There is no better place for a relaxing, meandering day of sightseeing. Plovdiv is considered one of the oldest cities in Europe, its Published in printed mini guide format once per year. history going back to a Neolithic settlement dated at roughly Print run 10,000 copies 6000 B.C. -

LARGE HOSPITALS in BULGARIA *The Abbreviations UMBAL

LARGE HOSPITALS IN BULGARIA *The abbreviations UMBAL/ УМБАЛ and MBAL/ МБАЛ in Bulgarian stand for “(University) Multi- profiled hospital for active medical treatment”, and usually signify the largest municipal or state hospital in the city/ region. UMBALSM/ УМБАЛСМ includes also an emergency ward. **The abbreviation DKC/ ДКЦ in Bulgarian stands for “Center for diagnostics and consultations” CITY HOSPITAL CONTACTS State Emergency Medical Tel.: +359 73 886 954 BLAGOEVGRAD Service – 24/7 21, Bratya Miladinovi Str. https://www.csmp-bl.com/ Tel.: +359 73 8292329 60, Slavyanska Str. MBAL Blagoevgrad http://mbalblagoevgrad.com/ Tel.: +359 73 882 020 Puls Private Hospital 62, Slavyanska Str. http://bolnicapuls.com Tel.: *7070 UMBAL Burgas 9, Zornitsa Str. BURGAS http://mbalburgas.com/ Emergency: +359 890 122 150 Meden Rudnik area, Zone A MBAL Burgasmed https://hospitalburgasmed.bg/ Emergency: +359 56 845 083 13, Vazrazhdane Str. Location: N 42 29' 40,54" St. Sofia Medical Center E 27 28' 24,40" http://www.saintsofia.com/ Tel.:+359 391 64024 29, Hristo Botev Blvd. DIMITROVGRAD MBAL Sveta Ekaterina https://www.mbalstekaterina.eu/ Tel.: +359 58 600 723 24, Panayot Hitov Str. DOBRICH MBAL Dobrich http://www.mbal-dobrich.com/ Tel.: +359 66 800 243 MBAL Dr. Tota Venkova 1, Doctor Iliev-Detskia street GABROVO Gabrovo https://www.mbalgabrovo.com/ Tel.: +359 41862373; +359 889522041 GALABOVO MBAL Galabovo 10, Aleko Konstantinov Str. Tel.: +359 66 876 424 Apogei Angelov&Co Medical 1, Ivaylo street Center Tel.: +359 751 95 114 54, Stara Planina Str. GOTSE DELCHEV MBAL Ivan Skenderov http://mbal-gocedelchev.com/ Tel.: +359 38 606 700 49, Saedinenie Blvd. -

Identity, Nationalism, and Cultural Heritage Under Siege Balkan Studies Library

Identity, Nationalism, and Cultural Heritage under Siege Balkan Studies Library Editor-in-Chief Zoran Milutinović (University College London) Editorial Board Gordon N. Bardos (Columbia University) Alex Drace-Francis (University of Amsterdam) Jasna Dragović-Soso (Goldsmiths, University of London) Christian Voss, (Humboldt University, Berlin) Advisory Board Marie-Janine Calic (University of Munich) Lenard J. Cohen (Simon Fraser University Radmila Gorup (Columbia University) Robert M. Hayden (University of Pittsburgh) Robert Hodel (Hamburg University) Anna Krasteva (New Bulgarian University) Galin Tihanov (Queen Mary, University of London) Maria Todorova (University of Illinois) Andrew Wachtel (Northwestern University) VOLUME 14 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/bsl Identity, Nationalism, and Cultural Heritage under Siege Five Narratives of Pomak Heritage—From Forced Renaming to Weddings By Fatme Myuhtar-May LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Pomak bride in traditional attire. Ribnovo, Rhodope Mountains, Bulgaria. Photo courtesy Kimile Ulanova of Ribnovo. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Myuhtar-May, Fatme. Cultural heritage under siege : five narratives of Pomak heritage : from forced renaming to weddings / by Fatme Myuhtar-May. pages cm. — (Balkan studies library, ISSN 1877-6272 ; volume 14) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-27207-1 (hardback : acid-free paper) — ISBN 978-90-04-27208-8 (e-book) 1. Pomaks—Bulgaria—Social conditions. 2. Pomaks—Bulgaria—Social life and customs. 3. Pomaks— Bulgaria—Case studies. 4. Pomaks—Bulgaria—Biography. 5. Culture conflict—Bulgaria. 6. Culture conflict—Rhodope Mountains Region. 7. Bulgaria—Ethnic relations. 8. Rhodope Mountains Region— Ethnic relations. I. Title. DR64.2.P66M98 2014 305.6’970499—dc23 2014006975 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual ‘Brill’ typeface. -

Appendix 1 D Municipalities and Mountainous

National Agriculture and Rural Development Plan 2000-2006 APPENDIX 1 D MUNICIPALITIES AND MOUNTAINOUS SETTLEMENTS WITH POTENTIAL FOR RURAL TOURISM DEVELOPMENT DISTRICT MUNICIPALITIES MOUNTAINOUS SETTLEMENTS Municipality Settlements* Izgrev, Belo pole, Bistrica, , Buchino, Bylgarchevo, Gabrovo, Gorno Bansko(1), Belitza, Gotze Delchev, Garmen, Kresna, Hyrsovo, Debochica, Delvino, Drenkovo, Dybrava, Elenovo, Klisura, BLAGOEVGRAD Petrich(1), Razlog, Sandanski(1), Satovcha, Simitly, Blagoevgrad Leshko, Lisiia, Marulevo, Moshtanec, Obel, Padesh, Rilci, Selishte, Strumiani, Hadjidimovo, Jacoruda. Logodaj, Cerovo Sungurlare, Sredets, Malko Tarnovo, Tzarevo (4), BOURGAS Primorsko(1), Sozopol(1), Pomorie(1), Nesebar(1), Aitos, Kamenovo, Karnobat, Ruen. Aksakovo, Avren, Biala, Dolni Chiflik, Dalgopol, VARNA Valchi Dol, Beloslav, Suvorovo, Provadia, Vetrino. Belchevci, Boichovci, Voneshta voda, Vyglevci, Goranovci, Doinovci, VELIKO Elena, Zlataritsa, Liaskovets, Pavlikeni, Polski Veliko Dolni Damianovci, Ivanovci, Iovchevci, Kladni dial, Klyshka reka, Lagerite, TARNOVO Trambesh, Strajitsa, Suhindol. Tarnovo Mishemorkov han, Nikiup, Piramidata, Prodanovci, Radkovci, Raikovci, Samsiite, Seimenite, Semkovci, Terziite, Todorovci, Ceperanite, Conkovci Belogradchik, Kula, Chuprene, Boinitsa, Bregovo, VIDIN Gramada, Dimovo, Makresh, Novo Selo, Rujintsi. Mezdra, Krivodol, Borovan, Biala Slatina, Oriahovo, VRATZA Vratza Zgorigrad, Liutadjik, Pavolche, Chelopek Roman, Hairedin. Angelov, Balanite, Bankovci, Bekriite, Bogdanchovci, Bojencite, Boinovci, Boicheta, -

List of Released Real Estates in the Administration of the Ministry Of

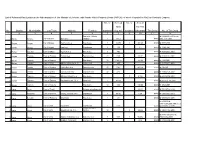

List of Released Real Estates in the Administration of the Ministry of Defence, with Private Public Property Deeds (PPPDs), of which Property the MoD is Allowed to Dispose No. of Built-up No. of Area of Area the Plot No. District Municipality City/Town Address Function Buildings (sq. m.) Facilities (decares) Title Deed No. of Title Deed 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Part of the Military № 874/02.05.1997 for the 1 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Slaveykov Hospital 1 545,4 PPPD whole real estate 2 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Kapcheto Area Storehouse 6 623,73 3 29,143 PPPD № 3577/2005 3 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Sarafovo Storehouse 6 439 5,4 PPPD № 2796/2002 4 Burgas Nesebar Town of Obzor Top-Ach Area Storehouse 5 496 PPPD № 4684/26.02.2009 5 Burgas Pomorie Town of Pomorie Honyat Area Barracks area 24 9397 49,97 PPPD № 4636/12.12.2008 6 Burgas Pomorie Town of Pomorie Storehouse 18 1146,75 74,162 PPPD № 1892/2001 7 Burgas Sozopol Town of Atiya Military station, by Bl. 11 Military club 1 240 PPPD № 3778/22.11.2005 8 Burgas Sredets Town of Sredets Velikin Bair Area Barracks area 17 7912 40,124 PPPD № 3761/05 9 Burgas Sredets Town of Debelt Domuz Dere Area Barracks area 32 5785 PPPD № 4490/24.04.2008 10 Burgas Tsarevo Town of Ahtopol Mitrinkovi Kashli Area Storehouse 1 0,184 PPPD № 4469/09.04.2008 11 Burgas Tsarevo Town of Tsarevo Han Asparuh Str., Bl. -

Priority Public Investments for Wastewater Treatment and Landfill of Waste

Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Develonment Europe and Central Asia Region 32051 BULGARIA Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL SEQUENCING STRATEGIES FOR EU ACCESSION PriorityPublic Investments for Wastewater Treatment and Landfill of Waste *t~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Public Disclosure Authorized IC- - ; s - o Fk - L - -. Public Disclosure Authorized The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized May 2004 - "Wo BULGARIA ENVIRONMENTAL SEQUENCING STRATEGIES FOR EU ACCESSION Priority Public Investments for Wastewater Treatment and Landfill of Waste May 2004 Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Development Europe and Central Asia Region Report No. 27770 - BUL Thefindings, interpretationsand conclusions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. Coverphoto is kindly provided by the external communication office of the World Bank County Office in Bulgaria. The report is printed on 30% post consumer recycledpaper. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ..................................................................... i Abbreviations and Acronyms ..................................................................... ii Summary ..................................................................... iiM Introduction.iii Wastewater.iv InstitutionalIssues .xvi Recommendations........... xvii Introduction ...................................................................... 1 Part I: The Strategic Settings for