Reconsidering State Formation and Indigenous Governance in Owo Kingdom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case Study of Owo LGA, Ondo State, Nigeria

The International Journal Of Engineering And Science (IJES) ||Volume||2 ||Issue|| 9 ||Pages|| 19-31||2013|| ISSN(e): 2319 – 1813 ISSN(p): 2319 – 1805 Geo-Information for Urban Waste Disposal and Management: The Case Study of Owo LGA, Ondo State, Nigeria *1Dr. Michael Ajide Oyinloye and 2Modebola-Fadimine Funmilayo Tokunbo Department of Urban and Regional Planning, School of Environmental Technology, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria --------------------------------------------------------ABSTRACT-------------------------------------------------- Management of waste is a global environmental issue that requires special attention for the maintenance of quality environment. It has been observed that amount, size, nature and complexity of waste generated by man are profoundly influenced by the level of urbanization and intensity of socio-economical development in a given settlement. The problem associated with its management ranges from waste generation, collection, transportation, treatment and disposal. The study involves a kind of multi-criteria evaluation method by using geographical information technology as a practical instrument to determine the most suitable sites of landfill location in Owo Local Government Area of Ondo state. Landsat Enhanced Thematic Mapper plus (ETM+) 2002 and updated 2012 were used to map the most suitable site for waste disposal in Owo LGA. The result indicates that sites were found within the study area. The most suitable sites in the study area are located at 200metre buffer to surface water and 100metre to major and minor roads. The selected areas have 2500metres buffer zone distance from urban areas (built up areas). The study purposes acceptable landfill sites for solid waste disposal in the study area. The results achieved in this study will help policy and decision makers to take appropriate decision in considering sanitary landfill sites. -

The Case of Ipele–Isua Highway

Daramola et al. Geo-Engineering (2018) 9:28 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40703-018-0096-9 TECHNICAL NOTE Open Access Premature failure of a major highway in southwestern Nigeria: the case of Ipele–Isua highway S. O. Daramola*, S. Malomo and Y. A. Asiwaju‑Bello *Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract Department of Applied Mineralogical, geochemical and geotechnical analyses were carried out to evaluate Geology, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria the contributions of geological and geotechnical properties of subgrade soils to the incidence of failure of the Ipele–Isua road, south-western Nigeria. Field observations showed that the road is in a very poor state of disrepair as major portions of the road alignment have failed. The road alignment is underlain in places by Quartz Schist, Banded Gneiss and Granite Gneiss. The results of the laboratory tests revealed that the natural moisture content ranges from 6.5 to 23.3%, liquid limit from 20.1 to 55.1%, plasticity index 5.2 to 22.2%. The grain size analysis showed that the amount of fnes ranges from 13 to 60.8%. Others are linear shrinkage between 2.9 and 11%, free swell between 16.67 and 41.94%, maximum dry density from 1520 to 1792.1 kg/m3 and CBR between− 2 and 17%. The specifc gravity ranges from 2.51 to 2.63. The major clay minerals present are kaolinite and dickite with dominance in 50% of the samples. Major oxides present are SiO2, Al2O3, Fe2O3, K2O. Na2O, MgO and CaO are generally less than 1%. Based on AASHTO classifcation, 19% of the samples are classifed as A-2-4, 33% classifed as A-2-6 while 44% classifed as A-7. -

Akeredolu Journey to Redemption

GGIANTIANT STRIDES AKEREDOLU JOURNEY TO REDEMPTION Abridged Version(First Steps and Giant Strides) 1 2 3 4 5 Abridged/Revised Version (First Steps and Giant Strides) GIANT STRIDES JOURNEY TO REDEMPTION Governor Oluwarotimi Odunayo Akeredolu(Aketi), SAN NGUHER ZAKI 6 7 contents INTRODUCTION 10 FOREWORD 12 JOB CREATION THROUGH AGRICULTURE, 14 ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND INDUSTRIALISATION. MASSIVE INFRASTRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT 66 AND MAINTENANACE. PROMOTION OF FUNCTIONAL EDUCATION 98 AND TECHNOLOGICAL GROWTH. PROVISION OF ACCESSIBLE AND QUALITATIVE 128 HEALTH CARE AND SOCIAL SERVICE DELIVERY. RURAL DEVELOPMENT AND 160 COMMUNITY EXTENSION SERVICES. SECURITY, LAW AND ORDER. 176 ARABINRIN IN ACTION . 202 ALLIANCES AND ENGAGEMENTS. 244 8 9 This book therefore enacts itself as speak with a certain force, clarity and an institutional memory which stores power which provide answers to the and unveils – in a rhythmic, cyclical questions: When is leadership? What Introduction and unending motion, Akeredolu’s should leadership do, now? And when he being of courage and This volume is an edited collection of experience ranging from anxiety, moral tapestry in Ondo State. is the nowness of now? No air, no character at the epicentre of the vivid pictures selected from frustration, disappointments, poverty, Why a book written in pictures? It is pretence and no colour. of heroism is the defining tonnes of photographic captures gloom and statism all of which for ease of reference and colour to The intrinsic value of the evidences characteristic of true and representations -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE SECTION A: PERSONAL DATA FULL NAME: ADEKIYA, ARUNA OLASEKAN DATE OF BIRTH: 15TH MAY, 1967 TOWN OWO LOCAL GOVT. AREA OWO STATE OF ORIGIN ONDO STATE NATIONALITY NIGERIAN MARITAL STATUS: MARRIED RELIGION CHRISTIANITY NUMBER OF CHILDREN: 3 CHILDREN CONTACT ADDRESS DEPT. OF CROP& SOILSCIENCES, LANDMARK UNIVERSITY, OMUARAN, KWARA STATE RESIDENTIAL ADDRESS: 11, ADEGBAYE STREET, OWO. ONDO STATE TELEPHONE NUMBER 08034813715 E-MAILADDRESS [email protected] CURRENT EMPLOYER LANDMARK UNIVERSITY, OMUARAN, KWARA STATE CURRENT POSITION LECTURER 1 CURRENT SALARY N205,367.00 Monthly Gross SECTION B: EDUCATIONAL HISTORY INSTITUTIONS ATTENDED WITH DATES: . ST. MARTINS PRIMARY SCHOOL, OWO 1973- 1979 . AHMADIYYA GRAMMAR SCHOOL, OWO 1979-1984 . IPELE COMMUNITY HIGH SCHOOL, IPELE-OWO 1984-1985 . FEDERAL UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY, AKURE 1989-1995 . FEDERAL UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY, AKURE 1998-2000 . FEDERAL UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY, AKURE 2008-2014 ACADEMIC QUALIFICATION OBTAINED WITH DATE: WASC 1985 B. AGRIC. TECH. (CROP PRODUCTION) 1995 M. AGRIC. TECH. (SOIL MANAGEMENT) 2000 Ph. D (SOIL MANAGEMENT) 2014 TECHING EXPERIENCE (a) Academic Rank Held: Ph. D (b) Academic Position Held: Lecturer 1 COURSE TAUGHT: SOS 513 Soil fertility & Plant Nutrition SOS 521 Soil Survey & Land Use Planning SOS 523 Principles of Soil Water Conservation and Management FPT431 Irrigation Soil and Water Conservation FPT 433 Soil Survey, Land Use and Agro Climatology SOS511 Soil Physics SOS311 Introductory Pedology and Soil Physics PUBLICATION AND JOURNALS Adekiya, A.O. and Agbede, T.M. (2016). Effect of methods and times of poultry manure application on soil and leaf nutrient concentrations, growth and fruit yield of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill). Journal of The Saudi Society of Agricultural Science. -

Yoruba Culture of Nigeria: Creating Space for an Endangered Specie

ISSN 1712-8358[Print] Cross-Cultural Communication ISSN 1923-6700[Online] Vol. 9, No. 4, 2013, pp. 23-29 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/j.ccc.1923670020130904.2598 www.cscanada.org Yoruba Culture of Nigeria: Creating Space for an Endangered Specie Adepeju Oti[a],*; Oyebola Ayeni[b] [a]Ph.D, Née Aderogba. Lead City University, Ibadan, Nigeria. [b] INTRODUCTION Ph.D. Lead City University, Ibadan, Nigeria. *Corresponding author. Culture refers to the cumulative deposit of knowledge, experience, beliefs, values, attitudes, meanings, Received 16 March 2013; accepted 11 July 2013 hierarchies, religion, notions of time, roles, spatial relations, concepts of the universe, and material objects Abstract and possessions acquired by a group of people in the The history of colonisation dates back to the 19th course of generations through individual and group Century. Africa and indeed Nigeria could not exercise striving (Hofstede, 1997). It is a collective programming her sovereignty during this period. In fact, the experience of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group of colonisation was a bitter sweet experience for the or category of people from another. The position that continent of Africa and indeed Nigeria, this is because the ideas, meanings, beliefs and values people learn as the same colonialist and explorers who exploited the members of society determines human nature. People are African and Nigerian economy; using it to develop theirs, what they learn, therefore, culture ultimately determine the quality in a person or society that arises from a were the same people who brought western education, concern for what is regarded as excellent in arts, letters, modern health care, writing and recently technology. -

2021 Budget Speech Delivered by the Governor of Ondo

2021 BUDGET SPEECH DELIVERED BY THE GOVERNOR OF ONDO STATE, ARAKUNRIN OLUWAROTIMI ODUNAYO AKEREDOLU (SAN) TO THE ONDO STATE HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY ON FRIDAY 27TH NOVEMBER, 2020 PROTOCOL It is with great delight that I stand before you today to present the fiscal estimate for 2021, which will be the fourth in the series of budgets I have been privileged to deliver to the people of Ondo State. I, therefore, give thanks to the Almighty God for his extravagant grace over my life. I also wish to reiterate my deep and heartfelt appreciation to the good people of this State, for keeping faith with us as demonstrated through the massive support we enjoyed throughout the electioneering campaigns and, particularly, during the gubernatorial election of 10th October, 2020. The confidence reposed in this administration means so much to me and will not be taken for granted. 2. It is worthy of note to eulogise and commend the level of patriotism, doggedness and maturity displayed by our people before, during and after the election. It is on record that the election was widely adjudged to be free and fair. The neutrality of Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) in the entire process has further raised the hope and belief of our people in our democracy. Without mincing words our people deserve to be celebrated for this feat and for the enlightenment in choosing continuityover sentiments. 3. Similarly, I wish to express my appreciation to this honourable House for the support you have given to this administration in the last three and half years. -

Hci Healthcare

HCI HEALTHCARE NATIONAL HOSPITAL NETWORK HEAD OFFICE: 296,HERBERT MACUALAY WAY,SABO, YABA, LAGOS Tel 01-4489820, 07030009099 Abuja Office: N01 Nairobi Street, Off Aminu Kano Crescent, Wuse 2, Abuja. Tel: 08052099066, 08052099071 Zonal Offices:Bauchi, Enugu, Kano, Port-Harcourt. Enquiries: 07034039098. Call Centre: 01-4489820. Fax: 01-4489821 E-mail:[email protected], Website: www.healthcare-ng.com STATE LGA TOWN/CITY HOSPITAL NAME ADDRESS PLAN TYPE Aba South Aba New Era Hospital Ltd 213/215 Azikiwe road, P.O.Box 2390, Aba All Plans Osisioma Living Word Hospital 5/7 Umuocham Street, Off Aba- Owerri Road, Aba All Plans Aba South Mendel Hospital 20, Tenant Road, Aba All Plans Obingwa Alpha Inland Hospital 36, Glass Industry Road, Aba All Plans Aba South St. Anthony's Hospital 62/80 Etche Road, Aba All Plans Aba North Zikora Medical Center Ogbor Hill Aba,Abia. All Plans ABIA Aba North Life Care Clinics Ltd 8, Eziukwu Road, P.O.Box 4742, Aba All Plans Umuahia South Umuahia Madonna Catholic Hospital Aba road, Umuahia All Plans Umuahia South Ngozi Hospital 9, Warri Street, All Plans Umuahia North Healing Cross Hospital Km 2, Bende Road, Umuahia All Plans Umuahia North OBIOMA HOSPITAL & MATERNIITY 21 School Rd,Umuahia All Plans Block 3, Amuzukwu Road, Amuzukwu Layout, (Near 85 Umuahia North Hammer Smith Medical Centre Uwalaka), Umuahai All Plans AMAC Abuja FCT Amana Medical Centre No 5.Ilorin Street, Off Ogbomosho Street, Area 8,Garki Titanium Ultra, Deluxe and Royal Plans AMAC Bio Royal Hospital 190, Okene/Jebba Close, Area 2, Garki All Plans No. -

The Forest Revenue System and Government Expenditure on Forestry in Nigeria

$ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ The forest revenue system and government expenditure on forestry in Nigeria A paper prepared for the FAO work-programme component on financing sustainable forest management Working paper: FSFM/WP/02 EUROPEAN COMMISSION DG VIII DEVELOPMENT THE FOREST REVENUE SYSTEM AND GOVERNMENT EXPENDITURE ON FORESTRY IN NIGERIA Federal Department of Forestry Federal Ministry of Environment Abuja, Nigeria Forestry Policy and Planning Division, Rome Regional Office for Africa, Accra April 2001 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Director, Information Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Viale -

National Assembly 1955 2013 Appropriation Total Recurrent Total Capital Total Allocation

FEDERAL GOVERNMENT OF NIGERIA 2013 BUDGET SUMMARY MINISTRY OF WORKS TOTAL OVERHEAD CODE TOTAL RECURRENT TOTAL PERSONNEL COST MDA COST =N= =N= =N= #VALUE! 0234001001 FEDERAL MINISTRY OF WORKS 5,126,324,844 4,545,265,692 344,575,711 4200689980.70 COUNCIL FOR THE REGULATION OF 0234005001 ENGINEERING IN NIGERIA (COREN) 189,686,219 168,396,390 18,085,726 -150,310,664 0234004001 FEDERAL ROAD MAINTENANCE AGENCY 25,219,058,866 1,495,663,078 18,344,937,586 16,849,274,508 0234003001 FEDERAL SCHOOL OF SURVEY, OYO 723,053,332 659,150,299 51,361,283 -607,789,016 OFFICE OF THE SURVEYOR-GENERAL OF THE 0234002001 FEDERATION 914,179,978 774,476,572 124,967,326 -649,509,246 0234006001 SURVEY COUNCIL OF NIGERIA 82,012,761 53,065,364 27,937,715 -25,127,649 REGIONAL CENTRE FOR TRAINING IN 0234007001 AEROSPACE SURVEY - 0 0 0 TOTAL 32,254,316,000 7,696,017,395 18,911,865,347 11,215,847,952 NATIONAL ASSEMBLY 1955 2013 APPROPRIATION TOTAL RECURRENT TOTAL CAPITAL TOTAL ALLOCATION =N= =N= =N= 4,889,841,403 141,487,997,912 146,377,839,315 186,482,116 200,000,000 386,482,116 19,840,600,664 21,663,871,961 41,504,472,625 710,511,582 236,000,000 946,511,582 899,443,898 3,975,930,127 4,875,374,025 81,003,079 310,000,000 391,003,079 0 300,000,000 300,000,000 26,607,882,742 168,173,800,000 194,781,682,742 NATIONAL ASSEMBLY 1956 2013 APPROPRIATION FEDERAL GOVERNMENT OF NIGERIA 2013 BUDGET 2013 BUDGET PROPOSAL ACCOUNT ACCOUNT NAME =N= CODE 0234001001 FEDERAL MINISTRY OF WORKS 02101 PERSONNEL COST ######### 21010101 CONSOLIDATED SALARY ####### 21020201 NHIS ####### 21020202 -

Comparison of Strength of Sandcrete Blocks Produce with Fine Aggregate from Different Sources

Nigerian Journal of Technology (NIJOTECH) Vol. 39, No. 2, April 2020, pp. 332 – 337 Copyright© Faculty of Engineering, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Print ISSN: 0331-8443, Electronic ISSN: 2467-8821 www.nijotech.com http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/njt.v39i2.2 COMPARISON OF STRENGTH OF SANDCRETE BLOCKS PRODUCE WITH FINE AGGREGATE FROM DIFFERENT SOURCES Bldr. A. O. Alejo * DEPARTMENT OF BUILDING TECHNOLOGY, RUFUS GIWA POLYTECHNIC, OWO, ONDO STATE, NIGERIA E-mail address: [email protected] ABSTRACT Sandcrete blocks comprise of water, natural sand cement. Sandcrete blocks are the building units used in the construction of wall and partitions. Diverse sizes of sandcrete blocks are used to construct free standing walls and building structure with load and non – load bearing units. This research work investigate and compared strength of sandcrete blocks produced with fine aggregate from different source in Owo local government area. The targeted areas within Owo local government are Emure, Ipele and Shagari. Sieve analysis was conducted on the samples and the result revealed that all the samples are good for sandcrete block production. Thirty six sandcrete cubes samples were mould. The mix proportion 1:6 was used. Batching by volume was adopted. Curing was done by full immersion of sandcrete and compressive strength test was carried out on each specimen at 7, 14. 21 and 28 days respectively. The percentage of fine aggregate used in this research was 100% for all samples. The results revealed that sandcrete blocks produced with fine aggregate from Ipele, Shagari and Emure gives compressive strength of 4,15N/MM2, 3.56N/MM2 and 5.48N/MM2 at 28 days respectively. -

A Study of NTA Akure Bejide, Oluwatoyin Abiola, Olaleye, Franklyn Akinola & Adekoya, Adeola Ojo

The International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Invention 6(12): 5746-5758, 2019 DOI: 10.18535/ijsshi/v6i12.02 ISSN: 2349-2031 © 2019, THEIJSSHI Case Study The Influence of Television Advertising in the Promotion of Yoruba Attires in Ondo State: a Study of NTA Akure Bejide, Oluwatoyin Abiola, Olaleye, Franklyn Akinola & Adekoya, Adeola Ojo Abstract: This paper is based on the influence of television advertising in the promotion of yoruba attires in Ondo State, “a study of NTA Akure”. The research work review related literature and was anchored on persuasive media and cultural conservative theories. It also employed survey design and questionnaire was administered to respondents of the selected three local government areas in Ondo State, but out of the 400 copies of questionnaire administered, 370 was duely attested and recovered for data analysis. The findings revealed that, NTA Akure advertising positively influenced the promotion of Yoruba attires in Ondo State. The study also revealed that, the level of the level of cognizance giving to the promotion of traditional attires especially Aso-Oke by NTA Akure is low. The study concludes that, television advertising has positively influenced the promotion of traditional attires in Yoruba society through assessment of NTA Akure viewers. This research work recommends that, NTA Akure should give much more cognizance to the promotion of the traditional attires through advertisement programme. It also recommends that the Ministry of Art and Culture in Ondo State should see NTA Akure as a medium through which cultural heritage especially traditional attires can be promoted. Key Words: Television Advertising, Advertising, Promotion, Yoruba Attires, Aso-Oke Introduction This does not happen through magic. -

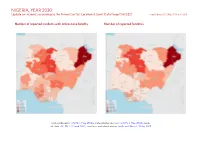

NIGERIA, YEAR 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021

NIGERIA, YEAR 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, 6 May 2018a; administrative divisions: GADM, 6 May 2018b; incid- ent data: ACLED, 12 March 2021; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 NIGERIA, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Violence against civilians 1045 605 2280 Conflict incidents by category 2 Protests 858 16 40 Development of conflict incidents from 2012 to 2020 2 Battles 844 627 3336 Riots 297 112 204 Methodology 3 Explosions / Remote 220 188 1900 Conflict incidents per province 4 violence Strategic developments 80 0 0 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 3344 1548 7760 Disclaimer 9 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). Development of conflict incidents from 2012 to 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). 2 NIGERIA, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known.