A Scientific Autobiography: S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tōhoku Rick Jardine

INFERENCE / Vol. 1, No. 3 Tōhoku Rick Jardine he publication of Alexander Grothendieck’s learning led to great advances: the axiomatic description paper, “Sur quelques points d’algèbre homo- of homology theory, the theory of adjoint functors, and, of logique” (Some Aspects of Homological Algebra), course, the concepts introduced in Tōhoku.5 Tin the 1957 number of the Tōhoku Mathematical Journal, This great paper has elicited much by way of commen- was a turning point in homological algebra, algebraic tary, but Grothendieck’s motivations in writing it remain topology and algebraic geometry.1 The paper introduced obscure. In a letter to Serre, he wrote that he was making a ideas that are now fundamental; its language has with- systematic review of his thoughts on homological algebra.6 stood the test of time. It is still widely read today for the He did not say why, but the context suggests that he was clarity of its ideas and proofs. Mathematicians refer to it thinking about sheaf cohomology. He may have been think- simply as the Tōhoku paper. ing as he did, because he could. This is how many research One word is almost always enough—Tōhoku. projects in mathematics begin. The radical change in Gro- Grothendieck’s doctoral thesis was, by way of contrast, thendieck’s interests was best explained by Colin McLarty, on functional analysis.2 The thesis contained important who suggested that in 1953 or so, Serre inveigled Gro- results on the tensor products of topological vector spaces, thendieck into working on the Weil conjectures.7 The Weil and introduced mathematicians to the theory of nuclear conjectures were certainly well known within the Paris spaces. -

Department of Physics and Astronomy 1

Department of Physics and Astronomy 1 PHSX 216 and PHSX 236, provide a calculus-based foundation in Department of Physics physics for students in physical science, engineering, and mathematics. PHSX 313 and the laboratory course, PHSX 316, provide an introduction and Astronomy to modern physics for majors in physics and some engineering and physical science programs. Why study physics and astronomy? Students in biological sciences, health sciences, physical sciences, mathematics, engineering, and prospective elementary and secondary Our goal is to understand the physical universe. The questions teachers should see appropriate sections of this catalog and major addressed by our department’s research and education missions range advisors for guidance about required physics course work. Chemistry from the applied, such as an improved understanding of the materials that majors should note that PHSX 211 and PHSX 212 are prerequisites to can be used for solar cell energy production, to foundational questions advanced work in chemistry. about the nature of mass and space and how the Universe was formed and subsequently evolved, and how astrophysical phenomena affected For programs in engineering physics (http://catalog.ku.edu/engineering/ the Earth and its evolution. We study the properties of systems ranging engineering-physics/), see the School of Engineering section of the online in size from smaller than an atom to larger than a galaxy on timescales catalog. ranging from billionths of a second to the age of the universe. Our courses and laboratory/research experiences help students hone their Graduate Programs problem solving and analytical skills and thereby become broadly trained critical thinkers. While about half of our majors move on to graduate The department offers two primary graduate programs: (i) an M.S. -

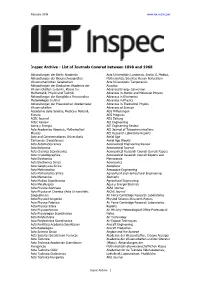

Inspec Archive - List of Journals Covered Between 1898 and 1968

February 2006 www.iee.org/inspec Inspec Archive - List of Journals Covered between 1898 and 1968 Abhandlungen der Berlin Akademie Acta Universitatis Lundensis. Sectio II. Medica, Abhandlungen der Braunschweigischen Mathematica, Scientiae Rerum Naturalium Wissenschaftlichen Gesellschaft Acta Universitatis Tamperensis Abhandlungen der Deutschen Akademie der Acustica Wissenschaften zu Berlin, Klasse fur Advanced Energy Conversion Mathematik, Physik und Technik Advances in Atomic and Molecular Physics Abhandlungen der Konigliches Preussisches Advances in Electronics Meteorologies Institut Advances in Physics Abhandlungen der Preussischen Akademieder Advances in Theoretical Physics Wissenschaften Advances of Science Accademia delle Scienze, Medico e Naturali, AEG Mitteilungen Ferrara AEG Progress ACEC Journal AEG Zeitung ACEC Review AEI Engineering Acero y Energia AEI Engineering Review Acta Academiae Aboensis, Mathematical AEI Journal of Telecommunications Physics AEI Research Laboratory Reports Acta and Commentationes Universitatis Aerial Age Tartuensis (Dorpatensis) Aerial Age Weekly Acta Automatica Sinica Aeronautical Engineering Review Acta Bolyaiana Aeronautical Journal Acta Chemica Scandinavica Aeronautical Research Council Current Papers Acta Crystallographica Aeronautical Research Council Reports and Acta Electronica Memoranda Acta Electronica Sinica Aeronautics Acta Geophysica Sinica Aeroplane Acta Mathematica Aerospace Engineering Acta Mathematica Sinica Agricultural and Horticultural Engineering Acta Mechanica Abstracts Acta Medica -

A Century of Mathematics in America, Peter Duren Et Ai., (Eds.), Vol

Garrett Birkhoff has had a lifelong connection with Harvard mathematics. He was an infant when his father, the famous mathematician G. D. Birkhoff, joined the Harvard faculty. He has had a long academic career at Harvard: A.B. in 1932, Society of Fellows in 1933-1936, and a faculty appointmentfrom 1936 until his retirement in 1981. His research has ranged widely through alge bra, lattice theory, hydrodynamics, differential equations, scientific computing, and history of mathematics. Among his many publications are books on lattice theory and hydrodynamics, and the pioneering textbook A Survey of Modern Algebra, written jointly with S. Mac Lane. He has served as president ofSIAM and is a member of the National Academy of Sciences. Mathematics at Harvard, 1836-1944 GARRETT BIRKHOFF O. OUTLINE As my contribution to the history of mathematics in America, I decided to write a connected account of mathematical activity at Harvard from 1836 (Harvard's bicentennial) to the present day. During that time, many mathe maticians at Harvard have tried to respond constructively to the challenges and opportunities confronting them in a rapidly changing world. This essay reviews what might be called the indigenous period, lasting through World War II, during which most members of the Harvard mathe matical faculty had also studied there. Indeed, as will be explained in §§ 1-3 below, mathematical activity at Harvard was dominated by Benjamin Peirce and his students in the first half of this period. Then, from 1890 until around 1920, while our country was becoming a great power economically, basic mathematical research of high quality, mostly in traditional areas of analysis and theoretical celestial mechanics, was carried on by several faculty members. -

The Emergence of Gravitational Wave Science: 100 Years of Development of Mathematical Theory, Detectors, Numerical Algorithms, and Data Analysis Tools

BULLETIN (New Series) OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Volume 53, Number 4, October 2016, Pages 513–554 http://dx.doi.org/10.1090/bull/1544 Article electronically published on August 2, 2016 THE EMERGENCE OF GRAVITATIONAL WAVE SCIENCE: 100 YEARS OF DEVELOPMENT OF MATHEMATICAL THEORY, DETECTORS, NUMERICAL ALGORITHMS, AND DATA ANALYSIS TOOLS MICHAEL HOLST, OLIVIER SARBACH, MANUEL TIGLIO, AND MICHELE VALLISNERI In memory of Sergio Dain Abstract. On September 14, 2015, the newly upgraded Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO) recorded a loud gravitational-wave (GW) signal, emitted a billion light-years away by a coalescing binary of two stellar-mass black holes. The detection was announced in February 2016, in time for the hundredth anniversary of Einstein’s prediction of GWs within the theory of general relativity (GR). The signal represents the first direct detec- tion of GWs, the first observation of a black-hole binary, and the first test of GR in its strong-field, high-velocity, nonlinear regime. In the remainder of its first observing run, LIGO observed two more signals from black-hole bina- ries, one moderately loud, another at the boundary of statistical significance. The detections mark the end of a decades-long quest and the beginning of GW astronomy: finally, we are able to probe the unseen, electromagnetically dark Universe by listening to it. In this article, we present a short historical overview of GW science: this young discipline combines GR, arguably the crowning achievement of classical physics, with record-setting, ultra-low-noise laser interferometry, and with some of the most powerful developments in the theory of differential geometry, partial differential equations, high-performance computation, numerical analysis, signal processing, statistical inference, and data science. -

National Academy of Sciences July 1, 1979 Officers

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES JULY 1, 1979 OFFICERS Term expires President-PHILIP HANDLER June 30, 1981 Vice-President-SAUNDERS MAC LANE June 30, 1981 Home Secretary-BRYCE CRAWFORD,JR. June 30, 1983 Foreign Secretary-THOMAS F. MALONE June 30, 1982 Treasurer-E. R. PIORE June 30, 1980 Executive Officer Comptroller Robert M. White David Williams COUNCIL Abelson, Philip H. (1981) Markert,C. L. (1980) Berg, Paul (1982) Nierenberg,William A. (1982) Berliner, Robert W. (1981) Piore, E. R. (1980) Bing, R. H. (1980) Ranney, H. M. (1980) Crawford,Bryce, Jr. (1983) Simon, Herbert A. (1981) Friedman, Herbert (1982) Solow, R. M. (1980) Handler, Philip (1981) Thomas, Lewis (1982) Mac Lane, Saunders (1981) Townes, Charles H. (1981) Malone, Thomas F. (1982) Downloaded by guest on September 30, 2021 SECTIONS The Academyis divided into the followingSections, to which membersare assigned at their own choice: (11) Mathematics (31) Engineering (12) Astronomy (32) Applied Biology (13) Physics (33) Applied Physical and (14) Chemistry Mathematical Sciences (15) Geology (41) Medical Genetics Hema- (16) Geophysics tology, and Oncology (21) Biochemistry (42) Medical Physiology, En- (22) Cellularand Develop- docrinology,and Me- mental Biology tabolism (23) Physiological and Phar- (43) Medical Microbiology macologicalSciences and Immunology (24) Neurobiology (51) Anthropology (25) Botany (52) Psychology (26) Genetics (53) Social and Political Sci- (27) Population Biology, Evo- ences lution, and Ecology (54) Economic Sciences In the alphabetical list of members,the numbersin parentheses, followingyear of election, indicate the respective Class and Section of the member. CLASSES The members of Sections are grouped in the following Classes: I. Physical and Mathematical Sciences (Sections 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16). -

Generalizations of the Kerr-Newman Solution

Generalizations of the Kerr-Newman solution Contents 1 Topics 1035 1.1 ICRANetParticipants. 1035 1.2 Ongoingcollaborations. 1035 1.3 Students ............................... 1035 2 Brief description 1037 3 Introduction 1039 4 Thegeneralstaticvacuumsolution 1041 4.1 Line element and field equations . 1041 4.2 Staticsolution ............................ 1043 5 Stationary generalization 1045 5.1 Ernst representation . 1045 5.2 Representation as a nonlinear sigma model . 1046 5.3 Representation as a generalized harmonic map . 1048 5.4 Dimensional extension . 1052 5.5 Thegeneralsolution . 1055 6 Tidal indicators in the spacetime of a rotating deformed mass 1059 6.1 Introduction ............................. 1059 6.2 The gravitational field of a rotating deformed mass . 1060 6.2.1 Limitingcases. 1062 6.3 Circularorbitsonthesymmetryplane . 1064 6.4 Tidalindicators ........................... 1065 6.4.1 Super-energy density and super-Poynting vector . 1067 6.4.2 Discussion.......................... 1068 6.4.3 Limit of slow rotation and small deformation . 1069 6.5 Multipole moments, tidal Love numbers and Post-Newtonian theory................................. 1076 6.6 Concludingremarks . 1077 7 Neutrino oscillations in the field of a rotating deformed mass 1081 7.1 Introduction ............................. 1081 7.2 Stationary axisymmetric spacetimes and neutrino oscillation . 1082 7.2.1 Geodesics .......................... 1083 1033 Contents 7.2.2 Neutrinooscillations . 1084 7.3 Neutrino oscillations in the Hartle-Thorne metric . 1085 7.4 Concludingremarks . 1088 8 Gravitational field of compact objects in general relativity 1091 8.1 Introduction ............................. 1091 8.2 The Hartle-Thorne metrics . 1094 8.2.1 The interior solution . 1094 8.2.2 The Exterior Solution . 1096 8.3 The Fock’s approach . 1097 8.3.1 The interior solution . -

Vector and Tensor Analysis, 1950, Harry Lass, 0177610514, 9780177610516, Mcgraw- Hill, 1950

Vector and tensor analysis, 1950, Harry Lass, 0177610514, 9780177610516, McGraw- Hill, 1950 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1CHWNWq http://www.powells.com/s?kw=Vector+and+tensor+analysis DOWNLOAD http://goo.gl/RBcy2 https://itunes.apple.com/us/book/Vector-and-tensor-analysis/id439454683 http://bit.ly/1lGfW8S Vector & Tensor Analysis , U.Chatterjee & N.Chatterjee, , , . Tensor Calculus A Concise Course, Barry Spain, 2003, Mathematics, 125 pages. A compact exposition of the theory of tensors, this text also illustrates the power of the tensor technique by its applications to differential geometry, elasticity, and. The Art of Modeling Dynamic Systems Forecasting for Chaos, Randomness and Determinism, Foster Morrison, Mar 7, 2012, Mathematics, 416 pages. This text illustrates the roles of statistical methods, coordinate transformations, and mathematical analysis in mapping complex, unpredictable dynamical systems. It describes. Partial differential equations in physics , Arnold Sommerfeld, Jan 1, 1949, Mathematics, 334 pages. Partial differential equations in physics. Tensor Calculus , John Lighton Synge, Alfred Schild, 1978, Mathematics, 324 pages. "This book is an excellent classroom text, since it is clearly written, contains numerous problems and exercises, and at the end of each chapter has a summary of the. Vector and tensor analysis , Harry Lass, 1950, Mathematics, 347 pages. Abstract Algebra and Solution by Radicals , John Edward Maxfield, Margaret W. Maxfield, 1971, Mathematics, 209 pages. Easily accessible undergraduate-level text covers groups, polynomials, Galois theory, radicals, much more. Features many examples, illustrations and commentaries as well as 13. Underwater Missile Propulsion A Selection of Authoritative Technical and Descriptive Papers, Leonard Greiner, 1968, Fleet ballistic missile weapons systems, 502 pages. -

Appendix E Nobel Prizes in Nuclear Science

Nuclear Science—A Guide to the Nuclear Science Wall Chart ©2018 Contemporary Physics Education Project (CPEP) Appendix E Nobel Prizes in Nuclear Science Many Nobel Prizes have been awarded for nuclear research and instrumentation. The field has spun off: particle physics, nuclear astrophysics, nuclear power reactors, nuclear medicine, and nuclear weapons. Understanding how the nucleus works and applying that knowledge to technology has been one of the most significant accomplishments of twentieth century scientific research. Each prize was awarded for physics unless otherwise noted. Name(s) Discovery Year Henri Becquerel, Pierre Discovered spontaneous radioactivity 1903 Curie, and Marie Curie Ernest Rutherford Work on the disintegration of the elements and 1908 chemistry of radioactive elements (chem) Marie Curie Discovery of radium and polonium 1911 (chem) Frederick Soddy Work on chemistry of radioactive substances 1921 including the origin and nature of radioactive (chem) isotopes Francis Aston Discovery of isotopes in many non-radioactive 1922 elements, also enunciated the whole-number rule of (chem) atomic masses Charles Wilson Development of the cloud chamber for detecting 1927 charged particles Harold Urey Discovery of heavy hydrogen (deuterium) 1934 (chem) Frederic Joliot and Synthesis of several new radioactive elements 1935 Irene Joliot-Curie (chem) James Chadwick Discovery of the neutron 1935 Carl David Anderson Discovery of the positron 1936 Enrico Fermi New radioactive elements produced by neutron 1938 irradiation Ernest Lawrence -

Mathematical Genealogy of the Wellesley College Department Of

Nilos Kabasilas Mathematical Genealogy of the Wellesley College Department of Mathematics Elissaeus Judaeus Demetrios Kydones The Mathematics Genealogy Project is a service of North Dakota State University and the American Mathematical Society. http://www.genealogy.math.ndsu.nodak.edu/ Georgios Plethon Gemistos Manuel Chrysoloras 1380, 1393 Basilios Bessarion 1436 Mystras Johannes Argyropoulos Guarino da Verona 1444 Università di Padova 1408 Cristoforo Landino Marsilio Ficino Vittorino da Feltre 1462 Università di Firenze 1416 Università di Padova Angelo Poliziano Theodoros Gazes Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo 1477 Università di Firenze 1433 Constantinople / Università di Mantova Università di Mantova Leo Outers Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Demetrios Chalcocondyles Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Thomas à Kempis Rudolf Agricola Alessandro Sermoneta Gaetano da Thiene Heinrich von Langenstein 1485 Université Catholique de Louvain 1493 Università di Firenze 1452 Mystras / Accademia Romana 1478 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1363, 1375 Université de Paris Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro François Dubois Jean Tagault Janus Lascaris Matthaeus Adrianus Pelope Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Jan Standonck Alexander Hegius Pietro Roccabonella Nicoletto Vernia Johannes von Gmunden 1504, 1515 Université Catholique de Louvain 1499, 1508 Università di Padova 1516 Université de Paris 1472 Università di Padova 1477, 1481 Universität Basel / Université de Poitiers 1474, 1490 Collège Sainte-Barbe -

An Interpretation of Milne Cosmology

An Interpretation of Milne Cosmology Alasdair Macleod University of the Highlands and Islands Lews Castle College Stornoway Isle of Lewis HS2 0XR UK [email protected] Abstract The cosmological concordance model is consistent with all available observational data, including the apparent distance and redshift relationship for distant supernovae, but it is curious how the Milne cosmological model is able to make predictions that are similar to this preferred General Relativistic model. Milne’s cosmological model is based solely on Special Relativity and presumes a completely incompatible redshift mechanism; how then can the predictions be even remotely close to observational data? The puzzle is usually resolved by subsuming the Milne Cosmological model into General Relativistic cosmology as the special case of an empty Universe. This explanation may have to be reassessed with the finding that spacetime is approximately flat because of inflation, whereupon the projection of cosmological events onto the observer’s Minkowski spacetime must always be kinematically consistent with Special Relativity, although the specific dynamics of the underlying General Relativistic model can give rise to virtual forces in order to maintain consistency between the observation and model frames. I. INTRODUCTION argument is that a clear distinction must be made between models, which purport to explain structure and causes (the Edwin Hubble’s discovery in the 1920’s that light from extra- ‘Why?’), and observational frames which simply impart galactic nebulae is redshifted in linear proportion to apparent consistency and causality on observation (the ‘How?’). distance was quickly associated with General Relativity (GR), and explained by the model of a closed finite Universe curved However, it can also be argued this approach does not actually under its own gravity and expanding at a rate constrained by the explain the similarity in the predictive power of Milne enclosed mass. -

Resolving Hubble Tension with the Milne Model 3

Resolving Hubble tension with the Milne model* Ram Gopal Vishwakarma Unidad Acade´mica de Matema´ticas Universidad Auto´noma de Zacatecas, Zacatecas C. P. 98068, ZAC, Mexico [email protected] Abstract The recent measurements of the Hubble constant based on the standard ΛCDM cos- mology reveal an underlying disagreement between the early-Universe estimates and the late-time measurements. Moreover, as these measurements improve, the discrepancy not only persists but becomes even more significant and harder to ignore. The present situ- ation places the standard cosmology in jeopardy and provides a tantalizing hint that the problem results from some new physics beyond the ΛCDM model. It is shown that a non-conventional theory - the Milne model - which introduces a different evolution dynamics for the Universe, alleviates the Hubble tension significantly. Moreover, the model also averts some long-standing problems of the standard cosmology, for instance, the problems related with the cosmological constant, the horizon, the flat- ness, the Big Bang singularity, the age of the Universe and the non-conservation of energy. Keywords: Milne model; ΛCDM model; Hubble tension; SNe Ia observations; CMB observations. arXiv:2011.12146v1 [physics.gen-ph] 20 Nov 2020 1 Introduction The Hubble constant H0 is one of the most important parameters in cosmology which mea- sures the present rate of expansion of the Universe, and thereby estimates its size and age. This is done by assuming a cosmological model. However, the two values of H0 predicted by the standard ΛCDM model, one inferred from the measurements of the early Universe and the other from the late-time local measurements, seem to be in sever tension.