(Peshawar and Bannu), Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BANNU EDUCATION FACILITIES - KPK Lebgend College

70°30'0"E 70°40'0"E 70°50'0"E BANNU EDUCATION FACILITIES - KPK LeBgend College ! !> !> !> Town Ship, Bannu !> High School !>!> !>!> !> UNIVERSITY OF !> !B SCIENCE AND !> !> FR BANNU !>!>!> !> TECHNOLOGY, BANNU !> Higher Secondary !>!>!> !> !> !> !> !!> N. WAZIRASTAN !>!> !> ! !>!> !> KGN G G P S K O T K A U M A R !>!> !>!> !> ! B ! R !> ! !> d Masjid School S H A H (C H A S H M I) !>!> !>!> !> !> !> !> !> at Rd BB DISTRICT oTh !> Nizam KARAK K JAIL !> !> !>!> !> U !> !> Middle School !> !> !> !> T !> Baza!>r!> !> !> A ! ! Boza N !> !> D !> !>!> A Sa A Khel !> d !> !> G !> !>!>!> !> Model Primary School !> !> R G G P S K O TK A G U L !> !> r L !>!> !> aw !> A !> !> a !> A !> !> !> !>!> B !> R A U F K H A N P IR B A n !> !> GPS Z!>INDI K H E L D O M E L Sheri !> !> Primary School GGPS L !> !> GG!>PS R A KILLA !> !!> d SITTI !> !> G !> GPS LANDI L!>AN!DI !> Kula KILLA N !> !!> GMS DABAK KILLA KILLA !> !> !> !> A !>!> !>!!>!> ! GGPS ABADI GGPS ARAL GMPS !> !> !> !> T Technical Institute T SYED KHEL K GGPS WANDA HATI KHEL ! !!> !>!> GUL AHMED ! GPS ZARI !> SYED!> REHMAN U !>!> !> !> !>!> !> !> R GHAFAR !> !> !> !>!> ! !> !B !> !> R KAS KALA!> d GUL FAQEER GPS SHER !> KHUJARI !> !> !> !> R A !> !> !>!>!> !> GPS B GPS KURRM !> I !> !> !> !> R !> !> !> !> !> !> !> A !> !> !> V M !> !> !> !> al ALI BEZEN!B !> !!> !> University R E !> !> !> !> !> h !> JAM!>EER BIZEN KHEL U GARHI !> R GPS SOH!>BAT !> !> !>!>!> A M!> !>!> !> !>!>!>T !> !> !> !> KHEL !> H N !> !> !>a !> !> !>!> - !> !>!>!> !> !> S L !> m KHAN S!>U!>R!>ANI u !>!> !>!> !> !!> !> !> -

Afghan Refugees Camp Population in KP March, 2018

SOLUTION STRATEGY UNIT COMMISSIONERATE AFGHAN REFUGEES KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA, PESHAWAR March, 2018 CAMP WISE AFGHAN REFUGEES POLULATION IN KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA S/No Name of District Name of Admn Camp Cluster Camps Population FAM IND 1 Kababian 2,3 764 4194 Kababian Michani/Warsak 30 196 2 Badaber 2840 14438 3 Khazana Khazana / Wahid Gari 921 4434 4 Naguman 410 2437 5 Khurasan 376 2259 Mere Kachori, Zandai 541 3400 6 Peshawar Mera Kachori Baghbanan 2149 9770 7 Shamshatoo Gul Badin, Old/ Molvi Khalid 3631 18817 Sub-Total Peshawar 11662 59945 8 Utmanzai 535 3268 Munda - I-II 1007 5099 9 Munda Ekka Gund 363 1471 10 Hajizai 501 2880 Sub-total Charsadda 2406 12718 Charsadda Akora Khattak Akora new, Hawai, 4509 22606 11 Kheshki 210 1710 12 Khairabad Khairabad 1926 9239 13 Turkaman Turkaman/Jalozai 410 2820 Nowshera Sub-Total Nowshera 7055 36375 14 Lakhti Banda 294 2085 Kata Kani 1000 6007 15 Kata Kani Kotki 297 2054 Kahi-I-II 1020 7937 16 Kahi Doaba 46 1165 17 Darsamand I-II 1640 10916 Hangu 18 Thall Thall-I-II 1270 12035 Sub-Total Hangu 5567 42199 19 Gamkol Gamkol -I-II-III 4932 30713 Oblen 1338 8081 20 Oblen Jarma 375 1067 Ghulam Banda 1021 6208 21 Ghulam Banda Shin Dhand 236 1426 22 Chichana 611 3901 Sub-Total Kohat 8513 51396 23 Jalala Jalala 1,2,3 1496 8187 Baghicha 481 2743 24 Baghicha Kagan 249 1352 Mardan Sub-Total Mardan 2226 12282 25 Barakai 2013 12606 Barakai Fazal 810 2731 26 Gandaf 2823 18226 Swabi Sub-Total Swabi 5646 33563 27 Zangal Patai 696 4125 Sub-Total Malakand 696 4125 Malakand Kohat Koga 1680 7972 28 Buner Sub-Total Buner 1680 -

Bannu DRC Rapid Needs Assessment II November 2014

Rapid Needs Assessment II Summary of Findings - November 2014 Displaced Populations of North Waziristan Agency in District Bannu Union Councils: Koti Sadat, Fatma Khel, Bazar Ahmad Khan, Ghoriwala, Amandi, Kausar Fateh Khel, Bharat, Nar Jaffer & Khaujari Monitoring & Evaluation Unit, Danish Refugee Council, Pakistan 0 | 14 For further details please contact: [email protected] ; [email protected] DRC| DANISH REFUGEE COUNCIL Acronyms CoRe Community Restoration cluster DRC Danish Refugee Council FATA Federally Administered Tribal Areas FDMA FATA Disaster Management Authority GoP Government of Pakistan IVAP IDP Vulnerability Assessment & Profiling KII Key Informant Interviews KP Khyber Pakhtunkhwa MIRA Multi-sector Initial Rapid Assessment NADRA National Database & Registration Authority NWA North Waziristan Agency PDMA Provincial Disaster Management Authority PKR Pakistan Rupee RRS Return and Rehabilitation Strategy TDPs Temporarily Dislocated Persons UC Union Council UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees UNICEF United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund UNOCHA United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Monitoring & Evaluation Unit, Danish Refugee Council, Pakistan 1|14 For further details please contact: [email protected] ; [email protected] DRC| DANISH REFUGEE COUNCIL Introduction The present report provides a snapshot of some of the most pressing needs as of the 24th of November 2014 among the Temporarily Dislocated Persons1 (TDPs) from North Waziristan Agency (NWA) in nine union councils (UCs) of District Bannu: Koti Sadat, Fatma Khel, Bazar Ahmad Khan, Ghoriwala, Amandi, Kausar Fateh Khel, Bharat, Nar Jaffar & Khaujari. This report is based on the second2 Bannu rapid needs assessment conducted by Danish Refugee Council (DRC) in late November 2014, which focused specifically on needs within winterization, shelter and livelihoods – both in place of displacement and origin. -

Usg Humanitarian Assistance to Pakistan in Areas

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO CONFLICT-AFFECTED POPULATIONS IN PAKISTAN IN FY 2009 AND TO DATE IN FY 2010 Faizabad KEY TAJIKISTAN USAID/OFDA USAID/Pakistan USDA USAID/FFP State/PRM DoD Amu darya AAgriculture and Food Security S Livelihood Recovery PAKISTAN Assistance to Conflict-Affected y Local Food Purchase Populations ELogistics Economic Recovery ChitralChitral Kunar Nutrition Cand Market Systems F Protection r Education G ve Gilgit V ri l Risk Reduction a r Emergency Relief Supplies it a h Shelter and Settlements C e Food For Progress I Title II Food Assistance Shunji gol DHealth Gilgit Humanitarian Coordination JWater, Sanitation, and Hygiene B and Information Management 12/04/09 Indus FAFA N A NWFPNWFP Chilas NWFP AND FATA SEE INSET UpperUpper DirDir SwatSwat U.N. Agencies, E KohistanKohistan Mahmud-e B y Da Raqi NGOs AGCJI F Asadabad Charikar WFP Saidu KUNARKUNAR LowerLower ShanglaShangla BatagramBatagram GoP, NGOs, BajaurBajaur AgencyAgency DirDir Mingora l y VIJaKunar tro Con ImplementingMehtarlam Partners of ne CS A MalakandMalakand PaPa Li Î! MohmandMohmand Kabul Daggar MansehraMansehra UNHCR, ICRC Jalalabad AgencyAgency BunerBuner Ghalanai MardanMardan INDIA GoP e Cha Muzaffarabad Tithwal rsa Mardan dd GoP a a PeshawarPeshawar SwabiSwabi AbbottabadAbbottabad y enc Peshawar Ag Jamrud NowsheraNowshera HaripurHaripur AJKAJK Parachinar ber Khy Attock Punch Sadda OrakzaiOrakzai TribalTribal AreaArea Î! Adj.Adj. PeshawarPeshawar KurrumKurrum AgencyAgency Islamabad Gardez TribalTribal AreaArea AgencyAgency Kohat Adj.Adj. KohatKohat Rawalpindi HanguHangu Kotli AFGHANISTAN KohatKohat ISLAMABADISLAMABAD Thal Mangla reservoir TribalTribal AreaArea AdjacentAdjacent KarakKarak FATAFATA BannuBannu us Bannu Ind " WFP Humanitarian Hub NorthNorth WWaziristanaziristan BannuBannu SOURCE: WFP, 11/30/09 Bhimbar AgencyAgency SwatSwat" TribalTribal AreaArea " Adj.Adj. -

Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan

February 2002 Vol. 14, No. 2(G) AFGHANISTAN, IRAN, AND PAKISTAN CLOSED DOOR POLICY: Afghan Refugees in Pakistan and Iran “The bombing was so strong and we were so afraid to leave our homes. We were just like little birds in a cage, with all this noise and destruction going on all around us.” Testimony to Human Rights Watch I. MAP OF REFUGEE A ND IDP CAMPS DISCUSSED IN THE REPORT .................................................................................... 3 II. SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 III. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 IV. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ............................................................................................................................ 6 To the Government of Iran:....................................................................................................................................................................... 6 To the Government of Pakistan:............................................................................................................................................................... 7 To UNHCR :............................................................................................................................................................................................... -

List of Province-Wise Quarantine Facilities Sr Locations

LIST OF PROVINCE-WISE QUARANTINE FACILITIES SR LOCATIONS BEDS Islamabad 1. Hajji Camp 300 2. Pak-China Friendship Centre 50 Total 350 Balochistan 1. Turkish Colony, District Jaffarabad 50 2. Midwifery School, District Naseerabad 50 3. DHQ Hospital Kachi 50 4. Boys Highschool Gandawah, District Jhal Magsi 50 5. Boys Highschool Digri, District Sohbatpur 50 6. Sheikh Khalif Bin Zayed Hospital, District Quetta 56 7. Gynae & General Private Hospital, District Quetta 24 8. Customs House Taftan 17 9. Taftan Quarantine 4,950 10. PCSIR Laboratory Compound 600 Total 5,897 Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 1. Landi Kotal, District Khyber 102 2. Darazinda, District Dera Ismail Khan 200 3. Peshawar 500 4. Gomal Medical College, District Dera Ismail Khan 200 5. RHC Dassu, District Kohistan 2 6. RHC Shetyal, District Kohistan 2 7. GHSS Boys, District Mohmand 20 8. GHS Ekkaghund, District Mohmand 30 9. Hostel Bahai Daag AC Complex, District Mohmand 20 10. DHQ Hospital Nursing Hostel, District Bajaur 30 11. Type D Hospital Nawagai, District Bajaur 30 12. Type D Hospital Larkhalozo, District Bajaur 60 13. Post Graduate College, District Bajaur 50 14. Degree College Nawagai, District Bajaur 50 15. Degree College Barkhalozo, District Bajaur 50 16. Bachelor Hostel Daag Qilla, District Bajaur 20 17. BHU Dehrakai, District Bajaur 10 18. RHC Arang, District Bajaur 10 19. GHS Khar No-2, District Bajaur 20 20. Govt. Degree College Wari, District Dir Upper 55 21. Govt. Degree College, District Dir Upper 35 22. Govt. Technical College, District Nowshera 50 23. Govt. Post Graduate College, District Nowshera 100 24. GHSS Khairabad, District Nowshera 20 25. -

Audit Report on the Accounts of Local Governments District Bannu Audit

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF LOCAL GOVERNMENTS DISTRICT BANNU AUDIT YEAR 2018-19 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviation…………………………………………..…………………..………i Preface ................................................................................................................. ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................. iii SUMMARY TABLES & CHARTS ................................................................... vii I: Audit Work Statistics ...................................................................................... vii II: Audit observations Classified by Categories .................................................. vii III: Outcome Statistics ...................................................................................... viii IV: Table of Irregularities pointed out ................................................................. ix V: Cost Benefit Ratio .......................................................................................... ix CHAPTER-1 ....................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Local Governments Bannu ............................................................................. 1 1.1.1 Introduction .......................................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Comments on Budget and Accounts (Variance Analysis) .................... 5 1.1.3 Comments on the status of compliance with DAC / TAC Directives ..... 7 1.2 DISTRICT -

BU16D00400-1-No R/Wall & 1-No P/Wall at UC Bharat 875,000

DISTRICT Project Description BE 2018-19 Final Budget Releases Expenditure BANNU BU16D00400-1-No R/Wall & 1-No P/Wall at UC Bharat 875,000 875,000 875,000 875,000 BANNU BU16D00401-Const. of R/Wall & P/Band at UC Kakki-I 875,000 875,000 875,000 875,000 BANNU BU16D00402-Const. of R/Wall & P/Band at UC ShamshiKhel 134,000 134,000 134,000 134,000 BANNU BU16D00403-Const. of R/Wall & P/Band at UC Mandew 875,000 875,000 875,000 875,000 BANNU BU16D00404-Const. of R/Wall & P/Band at UC KhanderKhan khel 875,000 875,000 875,000 875,000 BANNU BU16D00405-Const. of R/Wall & P/Band at UC SlemaSikander Khel 875,000 875,000 875,000 875,000 BANNU BU16D00406-Const. of R/Wall & P/Band at UC Nurar 825,000 825,000 825,000 825,000 BANNU BU16D00407-Const. of R/Wall & P/Band at UC ShamshiKhel 184,000 184,000 184,000 184,000 BANNU BU16D00408-Const. of R/Wall & P/Band at UC JhanduKhel 825,000 825,000 825,000 825,000 BANNU BU16D00409-Const. of R/Wall & P/Band/Pond at UCDomel 865,000 865,000 865,000 865,000 BANNU BU16D00410-Const. of R/Wall & P/Band at UC MamaKhel 875,000 875,000 875,000 875,000 BANNU BU16D00411-Const. of R/Wall & P/Band/Pond at UCAsperka Waziran 875,000 875,000 875,000 875,000 BANNU BU16D00412-Const. of R/Wall & P/Band UC ZerakiPirba Khel 595,000 595,000 595,000 595,000 BANNU BU16D00413-Const. -

75190 Caswaname 13/06/02 16:20 Side 270

75190 Caswaname 13/06/02 16:20 Side 270 South-West Asia Major Developments For the first months of 2001, Afghanistan continued to experience the devastating effects of drought, human rights abuses, and continued conflict between the Taliban and Northern Alliance. Prior to September, attempts by the United Nations and donor governments to bring the warring Afghan factions to the negotiating table had failed. Despite this, some 21,000 refugees returned from Pakistan with UNHCR assistance. They were mostly Pashtuns who said they were going back to Afghanistan because they could no longer afford to live in Pakistan, where employment opportunities were becoming increasingly rare, and because they feared being deported. At the same time, more than 140,000 Afghans returned spontaneously from the Islamic Republic of Iran, without seeking assis- tance from UNHCR. Others, however, continued to flee to neighbouring countries in search of assistance. The Islamic Afghanistan Republic of Iran and Pakistan, meanwhile, adopted Islamic Republic of Iran a closed border policy and deported Afghans who Pakistan did not have the required travel documents. 75190 Caswaname 13/06/02 16:20 Side 271 South-West Asia South-West In the spring, in an apparent bid to deter Afghans ble cases to enter the country, authorising UNHCR from entering Pakistan, the Government of to establish a pre-registration camp near the border Pakistan stopped transferring newly arrived at Chaman, and to move new arrivals to new camps Afghans from a makeshift camp at Jalozai, where conditions were very bad, to more suitable Persons of Concern to UNHCR locations. Following an intervention by the UN Secretary General, a visit by the High Commis- Mln. -

Jalozai Camp Nowshera District- Photograph by Syed Haider Ali

Floods in Pakistan Pakistan Health Cluster Bulletin No 6 5 August, 2010 Out -patient consultation in a static clinic operating in Nowshera district-Photo by Syed Haider Ali-WHO-EHA Highlights: Around 1.6 million people have been affected overnight in Punjab. A multi cluster rapid assessment mission (MCRAM) has commenced on 5 August. Infrastructure damage is hampering access to public health facilities in multiple locations in Khyber Paktunkhwa. The flood waters continue to destroy South of Punjab while heavy rains crippled lives in upper Sindh. One alert of acute watery diarrhea was reported from Chendangari village of FR Peshawar area where 70 patients have been reported so far though unconfirmed sources WHO, Government and Health Cluster partners are continuing the health response and struggling to reach communities and individuals in areas which are inaccessible. Situation Overview and Current Scope of Disaster Exact figures of deaths are still not clear but at least over 1,500 people have lost their lives with over a thousand injured. Initial findings of a WFP assessment suggest that some 250,000 families or 1.8 million people would be in need of assistance in KPK alone. These figures may rise as more areas are becoming accessible. The number of flood affectees in Punjab province is reported to be nearly 1.4 million people. According to UNOCHA some 4 million people have been affected due to country wide floods in Pakistan. Currently the flood wave of Indus River is in Muzaffargarh district (Southern Punjab) and after devastating Kot Addu town, it has entered Kot Mithon. -

1 TRIBE and STATE in WAZIRISTAN 1849-1883 Hugh Beattie Thesis

1 TRIBE AND STATE IN WAZIRISTAN 1849-1883 Hugh Beattie Thesis presented for PhD degree at the University of London School of Oriental and African Studies 1997 ProQuest Number: 10673067 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673067 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 ABSTRACT The thesis begins by describing the socio-political and economic organisation of the tribes of Waziristan in the mid-nineteenth century, as well as aspects of their culture, attention being drawn to their egalitarian ethos and the importance of tarburwali, rivalry between patrilateral parallel cousins. It goes on to examine relations between the tribes and the British authorities in the first thirty years after the annexation of the Punjab. Along the south Waziristan border, Mahsud raiding was increasingly regarded as a problem, and the ways in which the British tried to deal with this are explored; in the 1870s indirect subsidies, and the imposition of ‘tribal responsibility’ are seen to have improved the position, but divisions within the tribe and the tensions created by the Second Anglo- Afghan War led to a tribal army burning Tank in 1879. -

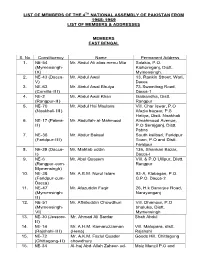

List of Members of the 4Th National Assembly of Pakistan from 1965- 1969 List of Members & Addresses

LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE 4TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF PAKISTAN FROM 1965- 1969 LIST OF MEMBERS & ADDRESSES MEMBERS EAST BENGAL S. No Constituency Name Permanent Address 1. NE-54 Mr. Abdul Ali alias menu Mia Solakia, P.O. (Mymensingh- Kishoreganj, Distt. IX) Mymensingh. 2. NE-43 (Dacca- Mr. Abdul Awal 13, Rankin Street, Wari, V) Dacca 3. NE-63 Mr. Abdul Awal Bhuiya 73-Swamibag Road, (Comilla-III) Dacca-1 4. NE-2 Mr. Abdul Awal Khan Gaibandha, Distt. (Rangpur-II) Rangpur 5. NE-70 Mr. Abdul Hai Maulana Vill. Char Iswar, P.O (Noakhali-III) Afazia bazaar, P.S Hatiya, Distt. Noakhali 6. NE-17 (Pabna- Mr. Abdullah-al-Mahmood Almahmood Avenue, II) P.O Serajganj, Distt. Pabna 7. NE-36 Mr. Abdur Bakaul South kalibari, Faridpur (Faridpur-III) Town, P.O and Distt. Faridpur 8. NE-39 (Dacca- Mr. Mahtab uddin 136, Shankari Bazar, I) Dacca-I 9. NE-6 Mr. Abul Quasem Vill. & P.O Ullipur, Distt. (Rangpur-cum- Rangpur Mymensingh) 10. NE-38 Mr. A.B.M. Nurul Islam 93-A, Klabagan, P.O. (Faridpur-cum- G.P.O. Dacca-2 Dacca) 11. NE-47 Mr. Afazuddin Faqir 26, H.k Banerjee Road, (Mymensingh- Narayanganj II) 12. NE-51 Mr. Aftabuddin Chowdhuri Vill. Dhamsur, P.O (Mymensingh- bhaluka, Distt. VI) Mymensingh 13. NE-30 (Jessore- Mr. Ahmad Ali Sardar Shah Abdul II) 14. NE-14 Mr. A.H.M. Kamaruzzaman Vill. Malopara, distt. (Rajshahi-III) (Hena) Rajshahi 15. NE-72 Mr. A.K.M. Fazlul Quader Goods Hill, Chittagong (Chittagong-II) chowdhury 16. NE-34 Al-haj Abd-Allah Zaheer-ud- Moiz Manzil P.O and (Faridpur-I) Deen (Lal Mian).