BEJS- Final Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-Kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L

Western Washington University Western CEDAR A Collection of Open Access Books and Books and Monographs Monographs 2008 Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L. Curley Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks Part of the Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Curley, David L., "Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal" (2008). A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs. 5. https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Books and Monographs at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Table of Contents Acknowledgements. 1. A Historian’s Introduction to Reading Mangal-Kabya. 2. Kings and Commerce on an Agrarian Frontier: Kalketu’s Story in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 3. Marriage, Honor, Agency, and Trials by Ordeal: Women’s Gender Roles in Candimangal. 4. ‘Tribute Exchange’ and the Liminality of Foreign Merchants in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 5. ‘Voluntary’ Relationships and Royal Gifts of Pan in Mughal Bengal. 6. Maharaja Krsnacandra, Hinduism and Kingship in the Contact Zone of Bengal. 7. Lost Meanings and New Stories: Candimangal after British Dominance. Index. Acknowledgements This collection of essays was made possible by the wonderful, multidisciplinary education in history and literature which I received at the University of Chicago. It is a pleasure to thank my living teachers, Herman Sinaiko, Ronald B. -

Indian Anthropology

INDIAN ANTHROPOLOGY HISTORY OF ANTHROPOLOGY IN INDIA Dr. Abhik Ghosh Senior Lecturer, Department of Anthropology Panjab University, Chandigarh CONTENTS Introduction: The Growth of Indian Anthropology Arthur Llewellyn Basham Christoph Von-Fuhrer Haimendorf Verrier Elwin Rai Bahadur Sarat Chandra Roy Biraja Shankar Guha Dewan Bahadur L. K. Ananthakrishna Iyer Govind Sadashiv Ghurye Nirmal Kumar Bose Dhirendra Nath Majumdar Iravati Karve Hasmukh Dhirajlal Sankalia Dharani P. Sen Mysore Narasimhachar Srinivas Shyama Charan Dube Surajit Chandra Sinha Prabodh Kumar Bhowmick K. S. Mathur Lalita Prasad Vidyarthi Triloki Nath Madan Shiv Raj Kumar Chopra Andre Beteille Gopala Sarana Conclusions Suggested Readings SIGNIFICANT KEYWORDS: Ethnology, History of Indian Anthropology, Anthropological History, Colonial Beginnings INTRODUCTION: THE GROWTH OF INDIAN ANTHROPOLOGY Manu’s Dharmashastra (2nd-3rd century BC) comprehensively studied Indian society of that period, based more on the morals and norms of social and economic life. Kautilya’s Arthashastra (324-296 BC) was a treatise on politics, statecraft and economics but also described the functioning of Indian society in detail. Megasthenes was the Greek ambassador to the court of Chandragupta Maurya from 324 BC to 300 BC. He also wrote a book on the structure and customs of Indian society. Al Biruni’s accounts of India are famous. He was a 1 Persian scholar who visited India and wrote a book about it in 1030 AD. Al Biruni wrote of Indian social and cultural life, with sections on religion, sciences, customs and manners of the Hindus. In the 17th century Bernier came from France to India and wrote a book on the life and times of the Mughal emperors Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb, their life and times. -

FINAL DISTRIBUTION.Xlsx

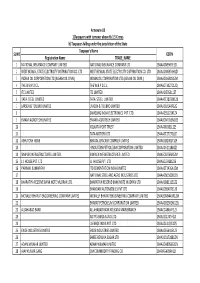

Annexure-1B 1)Taxpayers with turnover above Rs 1.5 Crores b) Taxpayers falling under the jurisdiction of the State Taxpayer's Name SL NO GSTIN Registration Name TRADE_NAME 1 NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LIMITED NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LTD 19AAACN9967E1Z0 2 WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD 19AAACW6953H1ZX 3 INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) 19AAACI1681G1ZM 4 THE W.B.P.D.C.L. THE W.B.P.D.C.L. 19AABCT3027C1ZQ 5 ITC LIMITED ITC LIMITED 19AAACI5950L1Z7 6 TATA STEEL LIMITED TATA STEEL LIMITED 19AAACT2803M1Z8 7 LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED 19AAACL0140P1ZG 8 SAMSUNG INDIA ELECTRONICS PVT. LTD. 19AAACS5123K1ZA 9 EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED 19AABCN7953M1ZS 10 KOLKATA PORT TRUST 19AAAJK0361L1Z3 11 TATA MOTORS LTD 19AAACT2727Q1ZT 12 ASHUTOSH BOSE BENGAL CRACKER COMPLEX LIMITED 19AAGCB2001F1Z9 13 HINDUSTAN PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED. 19AAACH1118B1Z9 14 SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. 19AAECS0765R1ZM 15 J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD 19AABCJ5928J2Z6 16 PARIMAL KUMAR RAY ITD CEMENTATION INDIA LIMITED 19AAACT1426A1ZW 17 NATIONAL STEEL AND AGRO INDUSTRIES LTD 19AAACN1500B1Z9 18 BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. 19AAACB8111E1Z2 19 BHANDARI AUTOMOBILES PVT LTD 19AABCB5407E1Z0 20 MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED 19AABCM9443R1ZM 21 BHARAT PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED 19AAACB2902M1ZQ 22 ALLAHABAD BANK ALLAHABAD BANK KOLKATA MAIN BRANCH 19AACCA8464F1ZJ 23 ADITYA BIRLA NUVO LTD. 19AAACI1747H1ZL 24 LAFARGE INDIA PVT. LTD. 19AAACL4159L1Z5 25 EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED 19AAACE6641E1ZS 26 SHREE RENUKA SUGAR LTD. 19AADCS1728B1ZN 27 ADANI WILMAR LIMITED ADANI WILMAR LIMITED 19AABCA8056G1ZM 28 AJAY KUMAR GARG OM COMMODITY TRADING CO. -

The High Court at Calcutta 150 Years : an Overview

1 2 The High Court at Calcutta 150 Years : An Overview 3 Published by : The Indian Law Institute (West Bengal State Unit) iliwbsu.in Printed by : Ashutosh Lithographic Co. 13, Chidam Mudi Lane Kolkata 700 006 ebook published by : Indic House Pvt. Ltd. 1B, Raja Kalikrishna Lane Kolkata 700 005 www.indichouse.com Special Thanks are due to the Hon'ble Justice Indira Banerjee, Treasurer, Indian Law Institute (WBSU); Mr. Dipak Deb, Barrister-at-Law & Sr. Advocate, Director, ILI (WBSU); Capt. Pallav Banerjee, Advocate, Secretary, ILI (WBSU); and Mr. Pradip Kumar Ghosh, Advocate, without whose supportive and stimulating guidance the ebook would not have been possible. Indira Banerjee J. Dipak Deb Pallav Banerjee Pradip Kumar Ghosh 4 The High Court at Calcutta 150 Years: An Overview तदॆततत- क्षत्रस्थ क्षत्रैयद क्षत्र यद्धर्म: ।`& 1B: । 1Bद्धर्म:1Bत्पटैनास्ति।`抜֘टै`抜֘$100 नास्ति ।`抜֘$100000000स्ति`抜֘$1000000000000स्थक्षत्रैयदत । तस्थ क्षत्रै यदर्म:।`& 1Bण । ᄡC:\Users\सत धर्म:" ।`&ﲧ1Bशैसतेधर्मेण।h अय अभलीयान् भलीयौसमाशयनास्ति।`抜֘$100000000 भलीयान् भलीयौसमाशयसर्म: ।`& य राज्ञाज्ञा एवम एवर्म: ।`& 1B ।। Law is the King of Kings, far more powerful and rigid than they; nothing can be mightier than Law, by whose aid, as by that of the highest monarch, even the weak may prevail over the strong. Brihadaranyakopanishad 1-4.14 5 Copyright © 2012 All rights reserved by the individual authors of the works. All rights in the compilation with the Members of the Editorial Board. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the copyright holders. -

In Search of Nationalist Trends in Indian Anthropology: Opening a New Discourse

OCCASIONAL PAPER 62 In search of nationalist trends in Indian anthropology: opening a new discourse Abhijit Guha September 2018 INSTITUTE OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES KOLKATA DD 27/D, Sector I, Salt Lake, Kolkata 700 064 Phone : +91 33 2321-3120/21 Fax : +91 33 2321-3119 E-mail : [email protected], Website: www.idsk.edu.in In search of nationalist trends in Indian anthropology: opening a new discourse Abhijit Guha1 Abstract There is little research on the history of anthropology in India. The works which have been done though contained a lot of useful data on the history of anthropology during the colonial and post- colonial periods have now become dated and they also did not venture into a search for the growth of nationalist anthropological writings by the Indian anthropologists in the pre and post independence periods. The conceptual framework of the discourse developed in this paper is derived from a critical reading of the anthropological texts produced by Indian anthropologists. This reading of the history of Indian anthropology is based on two sources. One source is the reading of the original texts by pioneering anthropologists who were committed to various tasks of nation building and the other is the reading of literature by anthropologists who regarded Indian anthropology simply as a continuation of the western tradition. There also existed a view that an Indian form of anthropology could be discerned in many ancient Indian texts and scriptures before the advent of a colonial anthropology introduced by the European scholars, administrators and missionaries in the Indian subcontinent. The readings from these texts are juxtaposed to write a new and critical history of Indian anthropology, which I have designated as the ‘new discourse’ in the title of this occasional paper. -

Caste, Society and Politics of North Bengal, 1869-1977

Caste, Society and Politics of North Bengal, 1869-1977 Thesis Submitted to the University of North Bengal, Darjeeling, West Bengal, for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Papiya Dutta Assistant Professor Syamsundar College Shyamsundar, Burdwan Supervisor Professor Ananda Gopal Ghosh Department of History University of North Bengal Raja Rammohanpur, Darjeeling West Bengal: 734013 University of North Bengal 2011 31 JAN 2013 R 9 54· 14 J) 91 9c_, ·~ Acknowledgement In the present work I have tried to analyze the nature of caste society of North Bengal and its distinctiveness from other parts of Bengal nay India. It also seeks to examine the changing process of caste solidarity and caste politics of the region concerned. I have also tried to find out the root of the problem of the region from historical point of view. I have been fortunate enough to get professor Ananda Gopal Ghosh as my supervisor who despite his busy schedule in academic and socio-cultural assignments and responsibilities have provided ·his invaluable and persistent guidance and directed me over the last five years by providing adequate source materials. I express my sincere gratitude for his active supervision and constant encouragement, advice throughout the course of my research work. In this work I have accumulated debts of many people and institutions and I am grateful to all of them. I am grateful to the learned scholars, academicians and authors whose work I have extremely consulted during the course of my study. This work could not have been possible without the co-operation of a large number of people from various fields. -

Annual Report 1979

INDIAN COUNCil OF SOCIAl SCIENCE RESEARCH ANNUAL REPORT 1979 .. 80 I. Programmes IIPA HOSTEL BUILDING, INDRAPRASTHA ESTATE RING ROAD, NEW DELHI-110002 Publication No. 122 1981 Non-Priced Printed at Rakesh Press, A-7 Naraina Industrial Area Phase II New Delhi-110028 on behalf of the Indian Council of Social Science Research, New Delhi. CONTENTS General 1 Research Promotion 2 Documentation 15 Publications 19 Data Archives 22 International Collaboration 24 Research Institutes 30 ICSSR Regional Centres 31 Other Programmes 43 Advisory Role 48 APPENDICES Members of the Council 50 Research Projects Sanctioned 53 Fellowships 62 Completed Research 71 List of Journals Indexed 78 Publication Grants Sanctioned 79 Social Scientists Given Financial Assistance to Attend Conferences/Seminars 80 Research Institutes 82 ANNUAL REPORT 1979-80 I General 1.01 This is the Eleventh Annual Report of the Indian Council of Social Science Research (ICSSR) pertaining to the year Aprill979 to March 1980. Composition of the ICSSR 1.02 The ICSSR, which is an autonomous organization established by the Government of India in 1969, is composed of 26 members : a Chairman, 18 social scientists, six represen tatives of the Government (all nominated by the Government) and a Member-Secretary (appointed by the ICSSR with the approval of the Government). 1. 03 During the year under review, the term of the following members came to an end : (1) Professor Y. K. Alagh, (2) Professor Abad Ahmed, (3) Professor A. K. Singh, (4) Professor V.P. Dutt, {5) Professor C. Parvathamma, and (6) Professor Iqbal Narain. · 1.04 The Government of India renominated Professor Iqbal Narain for a second term and nominated the folLowing new members to the vacancies : (1) Dr. -

Contents from the Desk of the Vice Chancellor

Contents From The Desk of The Vice Chancellor..............................................................................................................4 Maulana Abul Kalam Azad University of Technology, West Bengal....................................................................5 An Introduction..............................................................................................................................................5 Vision of The University..................................................................................................................................6 Mission of The University...............................................................................................................................6 Special Features..............................................................................................................................................6 ....................................................................................................................................................................6 JEMAT..........................................................................................................................................................7 PGET............................................................................................................................................................7 University Campuses......................................................................................................................................7 -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 1980-81 ■’i no-i -th GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND CULTURE (Department of Education and Department of Culture) NEW DELHI r y / ' i S ^ 3^ 1 - '> °6 ( CONTENTS DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Chapters Pages INTRODUCTORY (vii) 1. S c h o o l E d u c a t io n 1 2. H ig h e r E d u c a t io n a n d R e s e a r c h 14 3. T e c h n ic a l E d u c a t io n 3 0 4. S cholarships 36 5. Book Promotion and Copyright 39 6. Youth Services 43 7. P h y s ic a l E d u c a t io n a n d S p o r t s 4 6 8. L a n g u a g e s 53 9. I n d ia n N a t io n a l C o m m issio n f o r C o o p e r a t io n w it h U n e sc o 63 10. A d u l t E d u c a t io n 66 11. Education in the Union Territories 70 12. A c t iv it ie s in C o m m o n a n d C l e a r in g H o u se F u n c t io n s 76 DEPARTMENT OF CULTURE INTRODUCTORY (xv) 1. -

I Evolution of Indian Culture and Civilization

Unit-I Evolution of Indian culture and civilization Chapter 1- Palaeolithic culture Lower Palaeolithic culture Middle Palaeolithic culture Upper Palaeolithic culture Chapter 2- Mesolithic cultures Chapter 3-Neolithic culture Chapter 4- Chalcolithic cultures Chapter 5- Megalithic culture Chapter 6- Indus valley civilization Origins of Indus valley civilization Geography, environment and chronology of Indian valley civilization Urban planning in Indus valley civilization Trade and commerce in Indus valley civilization Religion of Indus people Theories regarding the decline of Indus valley civilization Chapter 7- Life of early Vedic people Chapter 8-Life of later Vedic people Chapter 9- Contribution of tribal cultures to Vedic culture Unit – II Paleo-anthropological evidences from India Chapter 1- Narmada basin and Siwaliks Chapter 2- Ramapithecus, Sivapithecus and Narmada man Chapter 3- Ethnoarchaeology Unit – III Impact of Buddhism, Jainism, islam and Christianity on India Chapter 1- Impact of Buddhism on Hindu culture Chapter 2- Impact of Jainism on Hindu culture Chapter 3- Impact of Islam on Indian culture Chapter 4- Impact of Christianity on Indian culture Unit - IV Population, biogenetic and linguistic characters of the people of India Chapter 1 Population of India Chapter 2 Growth of population in India Chapter 3 Effects of over population in India Chapter 4 Measures for controlling the rapid growth of population in India Chapter 5 Family planning in India Chapter 6 Guha’s classification of races in India Chapter 7 Negrito -

32 Cultural Diversity, Religious Syncretism and People of India

Bangladesh e-Journal of Sociology. Volume 3. Number 2, July 2006. 32 Cultural Diversity, Religious Syncretism and People of India: An Anthropological Interpretation N.K.Das ••• Abstract Ethnic origins, religions, and languages are the major sources of cultural diversity. India is a country incredible for its diversity; biological and cultural. However, the process of synthesis and integration has been extensively at work in most parts of India. Indeed ethnic identities and even the culture traits of Indian people have never been frozen in time or in space, they have been in state of flux. Though each group or community has a distinctive identity and ethos of its own, it does not exist in a social vacuum. Rather, it forms part of an extended and dynamic network. The sharing of space, regional ethos and cultural traits cut across ethnic and sectarian differences and bind the people together. Thus, we witness a firm balancing between cultural diversity and syncretism pervading the foundation of Indian civilization. Indeed by extension, such cultural phenomena are observable, to lesser or greater degree, in the entire sub continental – civilizational arena. The preexisting sub continental - civilizational continuum historically includes and encompasses ethnic diversity and admixture, linguistic heterogeneity as well as fusion, as well as synthesis in customs, behavioural patterns, beliefs and rituals. In the present era of growing cultural condensation, syncretism-synthesis is fast emerging as a prevailing event. This paper explores, by discussing ethnographic examples from different parts of India and beyond, the multi- dimensional and many layered contexts of reciprocally shared cultural realms and inter-religious and synthesized cultural formations, including common religious observances.