The Scientists and Grunge: Influence and Globalised Flows

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson

The Interplay of Authority, Masculinity, and Signification in the “Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014, Holly Johnson ii Abstract This thesis will deconstruct the "grunge killed '80s metal” narrative, to reveal the idealization by certain critics and musicians of that which is deemed to be authentic, honest, and natural subculture. The central theme is an analysis of the conflicting masculinities of glam metal and grunge music, and how these gender roles are developed and reproduced. I will also demonstrate how, although the idealized authentic subculture is positioned in opposition to the mainstream, it does not in actuality exist outside of the system of commercialism. The problematic nature of this idealization will be examined with regard to the layers of complexity involved in popular rock music genre evolution, involving the inevitable progression from a subculture to the mainstream that occurred with both glam metal and grunge. I will illustrate the ways in which the process of signification functions within rock music to construct masculinities and within subcultures to negotiate authenticity. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my academic advisor Dr. William Echard for his continued patience with me during the thesis writing process and for his invaluable guidance. I also would like to send a big thank you to Dr. James Deaville, the head of Music and Culture program, who has given me much assistance along the way. -

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

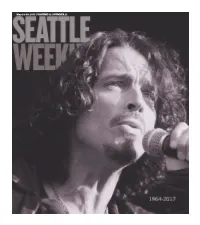

VOLUME 42 | NUMBER 21 Hen Chris Cornell Entered He Shrugged

May 24-30, 2017 | VOLUME 42 | NUMBER 21 hen Chris Cornell entered He shrugged. He spoke in short bursts of at a room, the air seemed to syllables. Soundgarden was split at the time, hum with his presence. All and he showed no interest in getting the eyes darted to him, then band back together. He showed little interest danced over his mop of in many of my questions. Until I noted he curls and lanky frame. He appeared to carry had a pattern of daring creative expression himself carelessly, but there was calculation outside of Soundgarden: Audioslave’s softer in his approach—the high, loose black side; bluesy solo eorts; the guitar-eschew- boots, tight jeans, and impeccable facial hair ing Scream with beatmaker Timbaland. his standard uniform. He was a rock star. At this, Cornell’s eyes sharpened. He He knew it. He knew you knew it. And that sprung forward and became fully engaged. didn’t make him any less likable. When he He got up and brought me an unsolicited left the stage—and, in my case, his Four bottled water, then paced a bit, talking all Seasons suite following a 2009 interview— the while. About needing to stay unpre- that hum leisurely faded, like dazzling dictable. About always trying new things. sunspots in the eyes. He told me that he wrote many songs “in at presence helped Cornell reach the character,” outside of himself. He said, “I’m pinnacle of popular music as front man for not trying to nd my musical identity, be- Soundgarden. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2019/20 Fadi Kheir Fadi LETTERS from the LEADERSHIP

ANNUAL REPORT 2019/20 Fadi Kheir Fadi LETTERS FROM THE LEADERSHIP The New York Philharmonic’s 2019–20 season certainly saw it all. We recall the remarkable performances ranging from Berlioz to Beethoven, with special pride in the launch of Project 19 — the single largest commissioning program ever created for women composers — honoring the ratification of the 19th Amendment. Together with Lincoln Center we unveiled specific plans for the renovation and re-opening of David Geffen Hall, which will have both great acoustics and also public spaces that can welcome the community. In March came the shock of a worldwide pandemic hurtling down the tracks at us, and on the 10th we played what was to be our final concert of the season. Like all New Yorkers, we tried to come to grips with the life-changing ramifications The Philharmonic responded quickly and in one week created NY Phil Plays On, a portal to hundreds of hours of past performances, to offer joy, pleasure, solace, and comfort in the only way we could. In August we launched NY Phil Bandwagon, bringing live music back to New York. Bandwagon presented 81 concerts from Chris Lee midtown to the far reaches of every one of the five boroughs. In the wake of the Erin Baiano horrific deaths of Black men and women, and the realization that we must all participate to change society, we began the hard work of self-evaluation to create a Philharmonic that is truly equitable, diverse, and inclusive. The severe financial challenge caused by cancelling fully a third of our 2019–20 concerts resulting in the loss of $10 million is obvious. -

Grunge Is Dead Is an Oral History in the Tradition of Please Kill Me, the Seminal History of Punk

THE ORAL SEATTLE ROCK MUSIC HISTORY OF GREG PRATO WEAVING TOGETHER THE DEFINITIVE STORY OF THE SEATTLE MUSIC SCENE IN THE WORDS OF THE PEOPLE WHO WERE THERE, GRUNGE IS DEAD IS AN ORAL HISTORY IN THE TRADITION OF PLEASE KILL ME, THE SEMINAL HISTORY OF PUNK. WITH THE INSIGHT OF MORE THAN 130 OF GRUNGE’S BIGGEST NAMES, GREG PRATO PRESENTS THE ULTIMATE INSIDER’S GUIDE TO A SOUND THAT CHANGED MUSIC FOREVER. THE GRUNGE MOVEMENT MAY HAVE THRIVED FOR ONLY A FEW YEARS, BUT IT SPAWNED SOME OF THE GREATEST ROCK BANDS OF ALL TIME: PEARL JAM, NIRVANA, ALICE IN CHAINS, AND SOUNDGARDEN. GRUNGE IS DEAD FEATURES THE FIRST-EVER INTERVIEW IN WHICH PEARL JAM’S EDDIE VEDDER WAS WILLING TO DISCUSS THE GROUP’S HISTORY IN GREAT DETAIL; ALICE IN CHAINS’ BAND MEMBERS AND LAYNE STALEY’S MOM ON STALEY’S DRUG ADDICTION AND DEATH; INSIGHTS INTO THE RIOT GRRRL MOVEMENT AND OFT-OVERLOOKED BUT HIGHLY INFLUENTIAL SEATTLE BANDS LIKE MOTHER LOVE BONE, THE MELVINS, SCREAMING TREES, AND MUDHONEY; AND MUCH MORE. GRUNGE IS DEAD DIGS DEEP, STARTING IN THE EARLY ’60S, TO EXPLAIN THE CHAIN OF EVENTS THAT GAVE WAY TO THE MUSIC. THE END RESULT IS A BOOK THAT INCLUDES A WEALTH OF PREVIOUSLY UNTOLD STORIES AND FRESH INSIGHT FOR THE LONGTIME FAN, AS WELL AS THE ESSENTIALS AND HIGHLIGHTS FOR THE NEWCOMER — THE WHOLE UNCENSORED TRUTH — IN ONE COMPREHENSIVE VOLUME. GREG PRATO IS A LONG ISLAND, NEW YORK-BASED WRITER, WHO REGULARLY WRITES FOR ALL MUSIC GUIDE, BILLBOARD.COM, ROLLING STONE.COM, RECORD COLLECTOR MAGAZINE, AND CLASSIC ROCK MAGAZINE. -

![D841o [Free Download] Love Death: the Murder of Kurt Cobain Online](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4019/d841o-free-download-love-death-the-murder-of-kurt-cobain-online-144019.webp)

D841o [Free Download] Love Death: the Murder of Kurt Cobain Online

d841o [Free download] Love Death: The Murder of Kurt Cobain Online [d841o.ebook] Love Death: The Murder of Kurt Cobain Pdf Free Par Max Wallace, Ian Halperin ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook Détails sur le produit Rang parmi les ventes : #289088 dans eBooksPublié le: 2014-03-20Sorti le: 2014-03- 20Format: Ebook Kindle | File size: 26.Mb Par Max Wallace, Ian Halperin : Love Death: The Murder of Kurt Cobain before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Love Death: The Murder of Kurt Cobain: Commentaires clientsCommentaires clients les plus utiles0 internautes sur 0 ont trouvé ce commentaire utile. A couper le soufflePar TichatDu vrai journalisme investigatif. Bien écrit, très bien recherché, objectif, avec des révélations inattendues et hallucinantes.Se lit tel qu'un thriller à en oublier presque qu'il s'agit malheureusement de faits réels.0 internautes sur 0 ont trouvé ce commentaire utile. GREAT SELLER +++ FAST, CLEAN,PERFECT ... WHAT ELSE ?Par guichardGREAT SELLER +++ FAST, CLEAN,PERFECT ... WHAT ELSE ?GREAT SELLER +++ FAST, CLEAN,PERFECT ... WHAT ELSE ?GREAT SELLER +++ FAST, CLEAN,PERFECT ... WHAT ELSE ? Présentation de l'éditeurTHE EXPLOSIVE INVESTIGATION INTO THE DEATH OF KURT COBAIN. Friday, 8th April 1994. Kurt Cobain's body was discovered in a room above a garage in Seattle. For the attending authorities, it was an open-and-shut case of suicide. What no one knew was Cobain had been murdered. That April, Cobain went missing for several days, or so it seemed: in fact, some people knew where he was, and one of them was Courtney Love. -

Lobby Loyde: the G.O.D.Father of Australian Rock

Lobby Loyde: the G.O.D.father of Australian rock Paul Oldham Supervisor: Dr Vicki Crowley A thesis submitted to The University of South Australia Bachelor of Arts (Honours) School of Communication, International Studies and Languages Division of Education, Arts, and Social Science Contents Lobby Loyde: the G.O.D.father of Australian rock ................................................. i Contents ................................................................................................................................... ii Table of Figures ................................................................................................................... iv Abstract .................................................................................................................................. ivi Statement of Authorship ............................................................................................... viiiii Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................. ix Chapter One: Overture ....................................................................................................... 1 Introduction: Lobby Loyde 1941 - 2007 ....................................................................... 2 It is written: The dominant narrative of Australian rock formation...................... 4 Oz Rock, Billy Thorpe and AC/DC ............................................................................... 7 Private eye: Looking for Lobby Loyde ......................................................................... -

Complete Band and Panel Listings Inside!

THE STROKES FOUR TET NEW MUSIC REPORT ESSENTIAL October 15, 2001 www.cmj.com DILATED PEOPLES LE TIGRE CMJ MUSIC MARATHON ’01 OFFICIALGUIDE FEATURING PERFORMANCES BY: Bis•Clem Snide•Clinic•Firewater•Girls Against Boys•Jonathan Richman•Karl Denson•Karsh Kale•L.A. Symphony•Laura Cantrell•Mink Lungs• Murder City Devils•Peaches•Rustic Overtones•X-ecutioners and hundreds more! GUEST SPEAKER: Billy Martin (Medeski Martin And Wood) COMPLETE D PANEL PANELISTS INCLUDE: BAND AN Lee Ranaldo/Sonic Youth•Gigi•DJ EvilDee/Beatminerz• GS INSIDE! DJ Zeph•Rebecca Rankin/VH-1•Scott Hardkiss/God Within LISTIN ININ STORESSTORES TUESDAY,TUESDAY, SEPTEMBERSEPTEMBER 4.4. SYSTEM OF A DOWN AND SLIPKNOT CO-HEADLINING “THE PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE TOUR” BEGINNING SEPTEMBER 14, 2001 SEE WEBSITE FOR DETAILS CONTACT: STEVE THEO COLUMBIA RECORDS 212-833-7329 [email protected] PRODUCED BY RICK RUBIN AND DARON MALAKIAN CO-PRODUCED BY SERJ TANKIAN MANAGEMENT: VELVET HAMMER MANAGEMENT, DAVID BENVENISTE "COLUMBIA" AND W REG. U.S. PAT. & TM. OFF. MARCA REGISTRADA./Ꭿ 2001 SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT INC./ Ꭿ 2001 THE AMERICAN RECORDING COMPANY, LLC. WWW.SYSTEMOFADOWN.COM 10/15/2001 Issue 735 • Vol 69 • No 5 CMJ MUSIC MARATHON 2001 39 Festival Guide Thousands of music professionals, artists and fans converge on New York City every year for CMJ Music Marathon to celebrate today's music and chart its future. In addition to keynote speaker Billy Martin and an exhibition area with a live performance stage, the event features dozens of panels covering topics affecting all corners of the music industry. Here’s our complete guide to all the convention’s featured events, including College Day, listings of panels by 24 topic, day and nighttime performances, guest speakers, exhibitors, Filmfest screenings, hotel and subway maps, venue listings, band descriptions — everything you need to make the most of your time in the Big Apple. -

Charles Peterson …And Everett True Is 481

Dwarves Photos: Charles Peterson …and Everett True is 481. 19 years on from his first Seattle jolly on the Sub Pop account, Plan B’s publisher-at-large jets back to the Pacific Northwest to meet some old friends, exorcise some ghosts and find out what happened after grunge left town. How did we get here? Where are we going? And did the Postal Service really sell that many records? Words: Everett True Transcripts: Natalie Walker “Heavy metal is objectionable. I don’t even know comedy genius, the funniest man I’ve encountered like, ‘I have no idea what you’re doing’. But he where that [comparison] comes from. People will in the Puget Sound8. He cracks me up. No one found trusted the four of us enough to let us go into the say that Motörhead is a metal band and I totally me attractive until I changed my name. The name studio for a weekend and record with Jack. It was disagree, and I disagree that AC/DC is a metal band. slides into meaninglessness. What is the Everett True essentially a demo that became our first single.” To me, those are rock bands. There’s a lot of Chuck brand in 2008? What does Sub Pop stand for, more Berry in Motörhead. It’s really loud and distorted and than 20 years after its inception? Could Sub Pop It’s in the focus. The first time I encountered Sub amplified but it’s there – especially in the earlier have existed without Everett True? Could Everett Pop, I had 24 hours to write up my first cover feature stuff. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Harper, A. (2016). "Backwoods": Rural Distance and Authenticity in Twentieth- Century American Independent Folk and Rock Discourse. Samples : Notizen, Projekte und Kurzbeiträge zur Popularmusikforschung(14), This is the published version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/15578/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Online-Publikationen der Gesellschaft für Popularmusikforschung / German Society for Popular Music Studies e. V. Hg. v. Ralf von Appen, André Doehring u. Thomas Phleps www.g f pm- samples.de/Samples1 4 / harper.pdf Jahrgang 14 (2015) – Version vom 5.10.2015 »BACKWOODS«: RURAL DISTANCE AND AUTHENTICITY IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AMERICAN INDEPENDENT FOLK AND ROCK DISCOURSE Adam Harper My recently completed PhD research (Harper 2014) has been an effort to trace a genealogy of an aesthetic within popular music discourse often known as »lo-fi.« This term, suggesting the opposite of hi-fi or high fidelity, became widely used in the late 1980s and early 1990s to describe a move- ment within indie (or alternative) popular music that was celebrated for its being recorded outside of the commercial studio system, typically at home on less than optimal or top-of-the-range equipment. -

The History of Rock Music: 1976-1989

The History of Rock Music: 1976-1989 New Wave, Punk-rock, Hardcore History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page (Copyright © 2009 Piero Scaruffi) The Golden Age of Heavy Metal (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") The pioneers 1976-78 TM, ®, Copyright © 2005 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. Heavy-metal in the 1970s was Blue Oyster Cult, Aerosmith, Kiss, AC/DC, Journey, Boston, Rush, and it was the most theatrical and brutal of rock genres. It was not easy to reconcile this genre with the anti-heroic ethos of the punk era. It could have seemed almost impossible to revive that genre, that was slowly dying, in an era that valued the exact opposite of machoism, and that was producing a louder and noisier genre, hardcore. Instead, heavy metal began its renaissance in the same years of the new wave, capitalizing on the same phenomenon of independent labels. Credit goes largely to a British contingent of bands, that realized how they could launch a "new wave of British heavy metal" during the new wave of rock music. Motorhead (1), formed by ex-Hawkwind bassist Ian "Lemmy" Kilminster, were the natural bridge between heavy metal, Stooges/MC5 and punk-rock. They played demonic, relentless rock'n'roll at supersonic speed: Iron Horse (1977), Metropolis (1979), Bomber (1979), Jailbait (1980), Iron Fist (1982), etc. -

Allison Wolfe Interviewed by John Davis Los Angeles, California June 15, 2017 0:00:00 to 0:38:33

Allison Wolfe Interviewed by John Davis Los Angeles, California June 15, 2017 0:00:00 to 0:38:33 ________________________________________________________________________ 0:00:00 Davis: Today is June 15th, 2017. My name is John Davis. I’m the performing arts metadata archivist at the University of Maryland, speaking to Allison Wolfe. Wolfe: Are you sure it’s the 15th? Davis: Isn’t it? Yes, confirmed. Wolfe: What!? Davis: June 15th… Wolfe: OK. Davis: 2017. Wolfe: Here I am… Davis: Your plans for the rest of the day might have changed. Wolfe: [laugh] Davis: I’m doing research on fanzines, particularly D.C. fanzines. When I think of you and your connection to fanzines, I think of Girl Germs, which as far as I understand, you worked on before you moved to D.C. Is that correct? Wolfe: Yeah. I think the way I started doing fanzines was when I was living in Oregon—in Eugene, Oregon—that’s where I went to undergrad, at least for the first two years. So I went off there like 1989-’90. And I was there also the year ’90-’91. Something like that. For two years. And I met Molly Neuman in the dorms. She was my neighbor. And we later formed the band Bratmobile. But before we really had a band going, we actually started doing a fanzine. And even though I think we named the band Bratmobile as one of our earliest things, it just was a band in theory for a long time first. But we wanted to start being expressive about our opinions and having more of a voice for girls in music, or women in music, for ourselves, but also just for things that we were into.