City Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phlltl'suphy, Robotics And'ftid . Dr

PASADENA, CALIFORNIA DECEMBER 9, 2002 Despite Invitation, Students Absent in Post.."Vectors Meeting nary meetings. the issue could wait no longer, oft By PHIL ~RN~T To students' deIi,ght,: Dr. BalJi- November 26th, Jo,u siqe~tepped ,' Stuae~ts \Von a majqr victort'last more ultimate!y tejected, V~etOl'S,. ~he ASCIT-mc standstill to. hand -::rifoi1fIiwilt5n Irrstitute'·Art-Corrimit-: Meanwhile, students-soughtto right select Ryan McDaniel '03 for the . z- ~"~ - ''"imn'7a6.Pl'etr'&'PeTlJna:-,:lip- "'past'wrongs- 'aQo.:this·time around. p'6~ition. There were sufficient ~Ast:I:r-,Ji'(f"mptiQn-,toIsea~-',in~r.t·a represen.tative'''ih''tfiemeet-' 'votes from the ASCIT BoD' in fa~ .... ' ", "trepJ¢se'n~Slti~e-?n ~~ d5~~' '~~gs 0ft~t?IAC alm.ed at select~ng vor of McDatliel to confirm his se- mittee',charged WIth selectmg a re- a replacement for Vectors. lection. piacement for Veciors. - ASGIT President Ted Jou '03 Last week, however, the Institute However, despite an explicit in- asked Pietro Perona, tht< temporary: Art Committee reconvened for the vitation, student leaders cited mis'- chair of the lAC, if he would con- first time since Baltimore's cancel D, Korta/The California Tech communication in their failure to sider the possibility of allowing a Humanities chairperson Jean Ensminger has rejected a second, last send a representative to last week's student to serve on the committee. Continued on Page 4, Column 1 ditch, Hail-Mary student petition to reinstate dismissed popular Rus first lAC meeting, raising concerns Dr. Perona, after debating Jou's sian literature and language professor George Cheron. -

Razorcake Issue #82 As A

RIP THIS PAGE OUT WHO WE ARE... Razorcake exists because of you. Whether you contributed If you wish to donate through the mail, any content that was printed in this issue, placed an ad, or are a reader: without your involvement, this magazine would not exist. We are a please rip this page out and send it to: community that defi es geographical boundaries or easy answers. Much Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. of what you will fi nd here is open to interpretation, and that’s how we PO Box 42129 like it. Los Angeles, CA 90042 In mainstream culture the bottom line is profi t. In DIY punk the NAME: bottom line is a personal decision. We operate in an economy of favors amongst ethical, life-long enthusiasts. And we’re fucking serious about it. Profi tless and proud. ADDRESS: Th ere’s nothing more laughable than the general public’s perception of punk. Endlessly misrepresented and misunderstood. Exploited and patronized. Let the squares worry about “fi tting in.” We know who we are. Within these pages you’ll fi nd unwavering beliefs rooted in a EMAIL: culture that values growth and exploration over tired predictability. Th ere is a rumbling dissonance reverberating within the inner DONATION walls of our collective skull. Th ank you for contributing to it. AMOUNT: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc., a California not-for-profit corporation, is registered as a charitable organization with the State of California’s COMPUTER STUFF: Secretary of State, and has been granted official tax exempt status (section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code) from the United razorcake.org/donate States IRS. -

Austinmusicawards2017.Pdf

Jo Carol Pierce, 1993 Paul Ray, Stevie Ray Vaughan, and PHOTOS BY MARTHA GRENON MARTHA BY PHOTOS Joe Ely, 1990 Daniel Johnston, Living in a Dream 1990 35 YEARS OF THE AUSTIN MUSIC AWARDS BY DOUG FREEMAN n retrospect, confrontation seemed almost a genre taking up the gauntlet after Nelson’s clashing,” admits Moser with a mixture of The Big Boys broil through trademark inevitable. Everyone saw it coming, but no outlaw country of the Seventies. Then Stevie pride and regret at the booking and subse- confrontational catharsis, Biscuit spitting one recalls exactly what set it off. Ray Vaughan called just prior to the date to quent melee. “What I remember of the night is beer onto the crowd during “Movies” and rip- I Blame the Big Boys, whose scathing punk ask if his band could play a surprise set. The that tensions started brewing from the outset ping open a bag of trash to sling around for a classed-up Austin Music Awards show booking, like the entire evening, transpired so between the staff of the Opera House, which the stage as the mosh pit gains momentum audience visited the genre’s desired effect on casually that Moser had almost forgotten until was largely made up of older hippies of a Willie during “TV.” the era. Blame the security at the Austin Stevie Ray and Jimmie Vaughan walked in Nelson persuasion who didn’t take very kindly About 10 minutes in, as the quartet sears into Opera House, bikers and ex-Navy SEALs from with Double Trouble and to the Big Boys, and the Big “Complete Control,” security charges from the Willie Nelson’s road crew, who typical of the proceeded to unleash a dev- ANY HISTORY OF Boys themselves, who were stage wings at the first stage divers. -

Razorcake Issue

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 #19 www.razorcake.com ight around the time we were wrapping up this issue, Todd hours on the subject and brought in visual aids: rare and and I went to West Hollywood to see the Swedish band impossible-to-find records that only I and four other people have RRRandy play. We stood around outside the club, waiting for or ancient punk zines that have moved with me through a dozen the show to start. While we were doing this, two young women apartments. Instead, I just mumbled, “It’s pretty important. I do a came up to us and asked if they could interview us for a project. punk magazine with him.” And I pointed my thumb at Todd. They looked to be about high-school age, and I guess it was for a About an hour and a half later, Randy took the stage. They class project, so we said, “Sure, we’ll do it.” launched into “Dirty Tricks,” ripped right through it, and started I don’t think they had any idea what Razorcake is, or that “Addicts of Communication” without a pause for breath. It was Todd and I are two of the founders of it. unreal. They were so tight, so perfectly in time with each other that They interviewed me first and asked me some basic their songs sounded as immaculate as the recordings. On top of questions: who’s your favorite band? How many shows do you go that, thought, they were going nuts. Jumping around, dancing like to a month? That kind of thing. -

Lado a Capítulo 1

Licenciatura en Comunicación y Cultura Compañías Discográficas Independientes: Las indies como propuesta alternativa de industria cultural en la Ciudad de México Trabajo recepcional que para obtener el título de Licenciado en Comunicación y Cultura Presenta Edgar Hugo Navarro Corona Directora de trabajo recepcional Mtra. Graciela Martínez Matías México D.F. Agosto 2010 SISTEMA BIBLIOTECARIO DE INFORMACIÓN Y DOCUMENTACIÓN UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE LA CIUDAD DE MÉXICO COORDINACIÓN ACADÉMICA RESTRICCIONES DE USO PARA LAS TESIS DIGITALES DERECHOS RESERVADOS© La presente obra y cada uno de sus elementos está protegido por la Ley Federal del Derecho de Autor; por la Ley de la Universidad Autónoma de la Ciudad de México, así como lo dispuesto por el Estatuto General Orgánico de la Universidad Autónoma de la Ciudad de México; del mismo modo por lo establecido en el Acuerdo por el cual se aprueba la Norma mediante la que se Modifican, Adicionan y Derogan Diversas Disposiciones del Estatuto Orgánico de la Universidad de la Ciudad de México, aprobado por el Consejo de Gobierno el 29 de enero de 2002, con el objeto de definir las atribuciones de las diferentes unidades que forman la estructura de la Universidad Autónoma de la Ciudad de México como organismo público autónomo y lo establecido en el Reglamento de Titulación de la Universidad Autónoma de la Ciudad de México. Por lo que el uso de su contenido, así como cada una de las partes que lo integran y que están bajo la tutela de la Ley Federal de Derecho de Autor, obliga a quien haga uso de la presente obra a considerar que solo lo realizará si es para fines educativos, académicos, de investigación o informativos y se compromete a citar esta fuente, así como a su autor ó autores. -

Complete Band and Panel Listings Inside!

THE STROKES FOUR TET NEW MUSIC REPORT ESSENTIAL October 15, 2001 www.cmj.com DILATED PEOPLES LE TIGRE CMJ MUSIC MARATHON ’01 OFFICIALGUIDE FEATURING PERFORMANCES BY: Bis•Clem Snide•Clinic•Firewater•Girls Against Boys•Jonathan Richman•Karl Denson•Karsh Kale•L.A. Symphony•Laura Cantrell•Mink Lungs• Murder City Devils•Peaches•Rustic Overtones•X-ecutioners and hundreds more! GUEST SPEAKER: Billy Martin (Medeski Martin And Wood) COMPLETE D PANEL PANELISTS INCLUDE: BAND AN Lee Ranaldo/Sonic Youth•Gigi•DJ EvilDee/Beatminerz• GS INSIDE! DJ Zeph•Rebecca Rankin/VH-1•Scott Hardkiss/God Within LISTIN ININ STORESSTORES TUESDAY,TUESDAY, SEPTEMBERSEPTEMBER 4.4. SYSTEM OF A DOWN AND SLIPKNOT CO-HEADLINING “THE PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE TOUR” BEGINNING SEPTEMBER 14, 2001 SEE WEBSITE FOR DETAILS CONTACT: STEVE THEO COLUMBIA RECORDS 212-833-7329 [email protected] PRODUCED BY RICK RUBIN AND DARON MALAKIAN CO-PRODUCED BY SERJ TANKIAN MANAGEMENT: VELVET HAMMER MANAGEMENT, DAVID BENVENISTE "COLUMBIA" AND W REG. U.S. PAT. & TM. OFF. MARCA REGISTRADA./Ꭿ 2001 SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT INC./ Ꭿ 2001 THE AMERICAN RECORDING COMPANY, LLC. WWW.SYSTEMOFADOWN.COM 10/15/2001 Issue 735 • Vol 69 • No 5 CMJ MUSIC MARATHON 2001 39 Festival Guide Thousands of music professionals, artists and fans converge on New York City every year for CMJ Music Marathon to celebrate today's music and chart its future. In addition to keynote speaker Billy Martin and an exhibition area with a live performance stage, the event features dozens of panels covering topics affecting all corners of the music industry. Here’s our complete guide to all the convention’s featured events, including College Day, listings of panels by 24 topic, day and nighttime performances, guest speakers, exhibitors, Filmfest screenings, hotel and subway maps, venue listings, band descriptions — everything you need to make the most of your time in the Big Apple. -

Pure Psychic Chance Radio: 2016 Jim Leftwich

Pure Psychic Chance Radio: 2016 Jim Leftwich Table of Contents Pure Psychic Chance Radio: Essays 2016 1. Permission slips: Thinking and breathing among John Crouse's UNFORBIDDENS 2. ACTs (improvised moderate militiamen: "Makeshift merger provost!") 3. Applied Experimental Sdvigology / Theoretical and Historical Sdvigology 4. HOW DO YOU THINK IT FEELS: On The Memorial Edition of Frank O’Hara’s In Memory of My Feelings 5. mirror lungeyser: On Cy Twombly, Poems to the Sea XIX 6. My Own Crude Rituals 7. A Preliminary Historiography of an Imagined Ongoing: 1830, 1896, 1962, 2028... 8. In The Recombinative Syntax Zone. Two Bennett poems partially erased by Lucien Suel. In the Recombinative Grammar Zone. 9. Three In The Morning: Reading 2 Poems By Bay Kelley from LAFT 35 10. The Glue Is On The Sausage: Reading A Poem by Crag Hill in LAFT 32 11. My Wrong Notes: On Joe Maneri, Microtones, Asemic Writing, The Iskra, and The Unnecessary Neurosis of Influence 12. Noisic Elements: Micro-tours, The Stool Sample Ensemble, Speaking Zaum To Power 13. TOTAL ASSAULT ON THE CULTURE: The Fuck You APO-33, Fantasy Politics, Mis-hearing the MC5... 14. DIRTY VISPO: Da Vinci To Pollock To d.a.levy 15. WHERE DO THEY LEARN THIS STUFF? An email exchange with John Crouse 16. FURTHER SUBVERSION SEEMS IN ORDER: Reading Poems by Basinski, Ackerman and Surllama in LAFT 33 17. A Collage by Tom Cassidy, Sent With The MinneDaDa 1984 Mail Art Show Doc, Postmarked Minneapolis MN 07 Sep '16 18. DIRTY VISPO II (Henri Michaux, Christian Dotremont, derek beaulieu, Scott MacLeod, Joel Lipman on d.a.levy, Lori Emerson on the history of the term "dirty concrete poetry", Albert Ayler, Jungian mandalas) 19. -

Fanatika017.Pdf

Cuarta época, otoño 2015, Nº 17 Stray cats • Los Gatos Carl & the Rythm Allstars Elvis Presley • James Dean Speedway Radio • Wild Record’s • Hasil Adkins • Grease • Hairspray Director Keshava Quintanar Cano Comité editorial José Roberto Cruz Núñez Daniel Cruz Vázquez Rita Lilia García Cerezo Reyna Rodríguez Roque Rodolfo Sánchez Rovirosa Fernando Velázquez Gallo Ana Laura Yáñez Piñón Nancy Benavides Martínez [email protected] Arte y diseño Isaac H. Hernández Hernández (IzaacH3) [email protected] Comunity manager Andrés García S. Corrección de estilo Édgar Mena L. Fanátika en facebook /Fanátika Consulta nuestras versiones electrónicas en www.issuu.com/fanatika Fanátika, la Revista Musical del CCH, proyecto INFOCAB PB402513, es una publicación de divulgación cultural y no persigue fines de lucro, los derechos de textos e imágenes aquí contenidos son propiedad de sus respectivos autores. Fanátika, cuarta época, número 17 tiene un tiraje de 1000 ejemplares. Se imprimió en marzo de 2015, en Gráficas Mateos, Tajín 184, Col. Narvarte, México D.F. tels: 5519-6392 y 5530-0791, [email protected] 2 El Rockabilly en la pantalla grande 6 Rita G. Cerezo La versión inadaptada de un clásico 12 Édgar Mena Hasil Adkins 16 Leonel Pérez Mosqueda Stray Cats 26 Keshava Quintanar Cano Wild Records, rock mexicano invade Estados Unidos 30 Samuel Nava Carl & the Rythm Allstars 34 Samuel Nava Rockabilly, pasión y estilo 40 Nancy Benavides Speedway Radio, Rockabilly para el mundo 44 Andrés García Serafín Escencia esencial de la poesía 50 Eduardo Daniel Hidalgo Olea En nuestro próximo número: Música en Inglés envía tus colaboraciones a [email protected] 3 Directorio UNAM Dr. -

OBSERVER Vol

OBSERVER Vol. 8 No. 5 November 17, 1997 Page 1 SUNY President Bowen Facing Possible Firing Controversial women’s conference raises the hackles of conservatives; trustees will decide issue tomorrow Nate Schwartz A Dangerous Across Intersection scene of three collisions Abigail Rosenberg Page 3 Ottaway: Powerful Words Can Shake Up the World Article 19 of Human Rights Declaration focus of walk Nate Schwartz Failings of Kline Food Redressed by Reps Menu plans and quality control need work, Food Committee says Andy Varyu Page 4 Behold Y’alls: Variety of Lectures, Films, Theatre Await the Savvy Student Calendar of Events summarizes the good, the bad, and the ugly with astounding perspicuity and wit “Best Kept Secret” “Outed” by Expert on Contraception Report from Planned Parenthood Kyra Carr Page 5 “Total Theatre” at Bard: Pelleas and Melisanda an Integrated Arts Triumph Modern melding of drama, dance, and music renders tragedy fluid, hypnotic Eric Fraser The Zine Scene More Noted from the “Underground” Elissa Nelson and Lauren Martin Page 7 Album Review The Usual Atmospheric Stuff? Electronica Joel Hunt Page 8 Movie Review: Boogie Nights: Thirteen Inches of Family Values Abigail Rosenberg Cartoon Page 9 Jesus Christ Superstar: Do You Think You’re What They Say You Are? First Bard Musical in 20+ years plays to capacity audiences and standing ovations Caitlin Jaynes Page 10 Horoscope The Effects of the Moon Nicole DiSalvo Restaurant Review The Stabl-izing Force of Foster’s Stephanie Schneider Page 11 Education in South Africa Stifled by Agenda -

Issue 195.Pmd

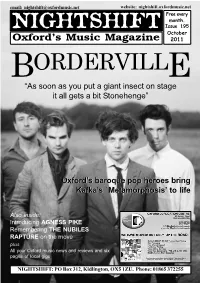

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 195 October Oxford’s Music Magazine 2011 BORDERVILLE “As soon as you put a giant insect on stage it all gets a bit Stonehenge” Oxford’sOxford’s baroquebaroque poppop heroesheroes bringbring Kafka’sKafka’s `Metamorphosis’`Metamorphosis’ toto lifelife Also inside: Introducing AGNESS PIKE Remembering THE NUBILES RAPTURE on the move plus All your Oxford music news and reviews and six pages of local gigs NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Truck Store is set to bow out with a weekend of live music on the 1st and 2nd October. Check with the shop for details. THE SUMMER FAYRE FREE FESTIVAL due to be held in South Park at the beginning of September was cancelled two days beforehand TRUCK STORE on Cowley Road after the organisers were faced with is set to close this month and will a severe weather warning for the be relocating to Gloucester Green weekend. Although the bad weather as a Rapture store. The shop, didn’t materialise, Gecko Events, which opened back in February as based in Milton Keynes, took the a partnership between Rapture in decision to cancel the festival rather Witney and the Truck organisation, than face potentially crippling will open in the corner unit at losses. With the festival a free Gloucester Green previously event the promoters were relying on bar and food revenue to cover occupied by Massive Records and KARMA TO BURN will headline this year’s Audioscope mini-festival. -

Allison Wolfe Interviewed by John Davis Los Angeles, California June 15, 2017 0:00:00 to 0:38:33

Allison Wolfe Interviewed by John Davis Los Angeles, California June 15, 2017 0:00:00 to 0:38:33 ________________________________________________________________________ 0:00:00 Davis: Today is June 15th, 2017. My name is John Davis. I’m the performing arts metadata archivist at the University of Maryland, speaking to Allison Wolfe. Wolfe: Are you sure it’s the 15th? Davis: Isn’t it? Yes, confirmed. Wolfe: What!? Davis: June 15th… Wolfe: OK. Davis: 2017. Wolfe: Here I am… Davis: Your plans for the rest of the day might have changed. Wolfe: [laugh] Davis: I’m doing research on fanzines, particularly D.C. fanzines. When I think of you and your connection to fanzines, I think of Girl Germs, which as far as I understand, you worked on before you moved to D.C. Is that correct? Wolfe: Yeah. I think the way I started doing fanzines was when I was living in Oregon—in Eugene, Oregon—that’s where I went to undergrad, at least for the first two years. So I went off there like 1989-’90. And I was there also the year ’90-’91. Something like that. For two years. And I met Molly Neuman in the dorms. She was my neighbor. And we later formed the band Bratmobile. But before we really had a band going, we actually started doing a fanzine. And even though I think we named the band Bratmobile as one of our earliest things, it just was a band in theory for a long time first. But we wanted to start being expressive about our opinions and having more of a voice for girls in music, or women in music, for ourselves, but also just for things that we were into. -

FINAL SALUTE Each Year We Note the Passing of Influential Creators, Performers, and Institutions

FINAL SALUTE Each year we note the passing of influential creators, performers, and institutions. These passings occurred between SoonerCon 28 and the original date for SoonerCon 29. American actress and singer Peggy Lipton passed away May 11, 2019. Her best-known acting role was as undercover cop Julie Barnes on The Mod Squad, 1968-1973. She won a new generation of fans when she ran the Double R Diner as Norma Jennings, in Twin Peaks. Doris Day was a big-band singer, TV and film actress, and talk-show host. She won several awards for comedy and popularity. She was also an activist for animal welfare, lending her star power to several organizations bearing her name. She died May 13, 2019. Domestic cat Tardar Sauce was better known as the meme she unwittingly founded: Grumpy Cat. Dwarfism contributed to her scowling face, which graced ads for Friskies and General Mills Honey Nut Cheerios. The frowning feline cashed in her lives on May 14, 2019. The career of the inspired Tim Conway began in 1962 and lasted through TV, movies, voice-overs, and video games. Among his noted appearances were the goofy Dorf; four years on McHale ‘s Navy; eleven years on The Carol Burnett Show; several solo TV shows; and as Barnacle Boy, 1999-2012, on SpongeBob SquarePants. Conway took his final bow on May 14, 2019. Born in China, I.M. Pei moved to America in 1935 and in 1948 became a professional architect. He designed the John F. Kennedy Library, which took until 1979 to complete. In 1962 he was selected by OKC’s Urban Renewal Authority to redesign our downtown.