Remapping Songdo: a Genealogy of a Smart City in South Korea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reformation of Mass Transportation System in Seoul Metropolitan Area

Reformation of Mass Transportation System in Seoul Metropolitan Area 2013. 11. Presenter : Dr. Sang Keon Lee Co-author: Dr. Sang Min Lee(KOTI) General Information Seoul (Area=605㎢, 10mill. 23.5%) - Population of South Korea : 51.8 Million (‘13) Capital Region (Area=11,730㎢, 25mill. 49.4%)- Size of South Korea : 99,990.5 ㎢ - South Korean Capital : Seoul 2 Ⅰ. Major changes of recent decades in Korea Korea’s Pathways at a glance 1950s 1960s 1970s 1980s 1990s 2000s Economic Economic Heavy-Chem. Stabilization-Growth- Economic Crisis & Post-war recovery Development takeoff Industry drive Balancing-Deregulation Restructuring Development of Balanced Territorial Post-war Growth pole Regional growth Promotion Industrialization regional Development reconstruction development Limit on urban growth base development Post-war Construction of Highways & National strategic networks Environ. friendly Transport reconstruction industrial railways Urban subway / New technology 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 Population 20,189 24,989 31,435 37,407 43,390 45,985 48,580 (1,000 pop.) GDP - 1,154 1,994 3,358 6,895 11,347 16,372 ($) No. Cars - - 127 528 3,395 12,059 17,941 (1,000 cars) Length of 25,683 27,169 40,244 46,950 56,715 88,775 105,565 Road(km) 3 Population and Size - Seoul-Metropoliotan Area · Regions : Seoul, Incheon, Gyeonggi · Radius : Seoul City 11~16 km Metro Seoul 4872 km Population Size Density (million) (㎢) (per ㎢) Seoul 10.36 605.3 17,115 Incheon 2.66 1,002.1 2,654 Gyeonggi 11.11 10,183.3 1,091 Total 24.13 11,790.7 2,047 4 III. -

Universidad Peruana De Ciencias Aplicadas Facultad

Caracterización de los procesos de consumo de los K- Dramas y videos musicales de K-Pop, y su incidencia en la construcción de la identidad y formas de socialización en la comunidad Hallyu de Lima. Una aproximación desde los fenómenos de audiencia en K-Dramas Descendants of the Sun y Goblin: The Lonely and Great God, y los fenómenos de tendencia musical de los grupos BIG BANG y Bangtan Boys; Beyond The Scene a.k.a BTS Item Type info:eu-repo/semantics/bachelorThesis Authors Mosquera Anaya, Heidy Winie Publisher Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas (UPC) Rights info:eu-repo/semantics/openAccess; Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Download date 10/10/2021 11:56:20 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10757/648589 UNIVERSIDAD PERUANA DE CIENCIAS APLICADAS FACULTAD DE COMUNICACIONES PROGRAMA ACADÉMICO DE COMUNICACIÓN AUDIOVISUAL Y MEDIOS INTERACTIVOS Caracterización de los procesos de consumo de los K-Dramas y videos musicales de K-Pop, y su incidencia en la construcción de la identidad y formas de socialización en la comunidad Hallyu de Lima. Una aproximación desde los fenómenos de audiencia en K-Dramas Descendants of the Sun y Goblin: The Lonely and Great God, y los fenómenos de tendencia musical de los grupos BIG BANG y Bangtan Boys; Beyond The Scene a.k.a BTS. TESIS Para optar el título profesional de Licenciado en Comunicación Audiovisual y Medios Interactivos AUTOR(A) Mosquera Anaya, Heidy Winie (0000-0003-4569-9612) ASESOR(A) Calderón Chuquitaype, Gabriel Raúl (0000-0002-1596-8423) Lima, 01 de Junio de 2019 DEDICATORIA A mis padres Abraham y Luz quienes con su amor, paciencia y esfuerzo me han permitido llegar a cumplir hoy un sueño más. -

Logistics Response to the Industry 4.0: the Physical Internet

Open Eng. 2016; 6:511–517 Review Article Open Access Marinko Maslarić*, Svetlana Nikoličić, and Dejan Mirčetić Logistics Response to the Industry 4.0: the Physical Internet DOI 10.1515/eng-2016-0073 Received Jun 25, 2016; accepted Aug 01, 2016 1 Introduction Abstract: Today’s mankind and all human activities are Maybe the key word of this century is digitalization. Dig- constantly changing and evolving in response to changes italization is present in all spheres of human activities. in technology, social and economic environments and cli- When it comes to business activities then digitalization mate. Those changes drive a “new” way of manufacturing is a personification of the concept Industry 4.0. That is, industry. That novelty could be described as the organiza- words such as mechanization, electrification and informa- tion of production processes based on technology and de- tization are key words for the first three industrial revolu- vices autonomously communicating with each other along tions respectively, so is digitalization, which includes the the value chain. Decision-makers have to address this nov- use of integrated Cyber-Physical Systems, the key word for elty (usually named as Industry 4.0) and try to develop the fourth industrial revolution or the Industry 4.0. The appropriate information systems, physical facilities, and term Industry 4.0 refers to a further developmental stage different kind of technologies capable of meeting thefu- in the organization and management of the entire value ture needs of economy. As a consequence, there is a need chain process involved in manufacturing industry [1–3]. for new paradigms of the way freight is move, store, real- The Industry 4.0 assumes the formation of global networks ize, and supply through the world (logistics system). -

Short Circuit: a Counter-Logistics Reader

SHORT-CIRCUIT a counterlogistics reader CONTENTS Introduction v Zad, Commune, Metropolis 1 Anonymous Logistics, Counterlogistics, and the 18 Communist Prospect Jasper Bernes Communist Measures in 64 Notre-Dame-Des-Landes Max L’Hameunasse The Cybernetic Hypothesis: Part IV 70 Tiqqun Communist Measures 88 Leon de Mattis Disaster Communism 112 Out of the Woods The Anthropocene 136 1882 Woodbine Choke Points: Mapping an Anticap- 198 italist Counterlogistics in California Degenerate Communism Further Reading 245 INTRODUCTION These days everything is about speed, flexibility and initiative. Goods are delivered to us before we order them, and criminals arrested before committing crimes. Mecha- nisms of control mirror mechanisms of proft, both in the “productive” sphere of crafting citizen-consumer subjects, and the disciplinary sphere of surveillance, monitoring, and repression. Knowledge of systems, networks, location and movement become ever more important for both the state and capital, just as that knowledge becomes ever more seamlessly integrated and indistinguishable. Tere are a few diferent words for this tendency. One word is cybernetics: the study of systems and networks, the conversion of human relations into an ecology of data points that can be tweaked and controlled but remains self-stabilizing. Cybernetics comes from the Greek kubernèsis, “to pilot or steer,” as in to steer economy, society. We want to disrupt the piloting of this ship, to take what detritus is usable and leave the rest to sink in the rising oceans. Above all, cybernetics seeks to know everything. Just as the liberal subject arose arm-in-arm with the com- modity—exchangeable, formally equal—the contemporary subject is tracked with the same precision as contemporary goods. -

Inclusive Growth in Seoul

Inclusive Growth in Seoul Policy Highlights About the OECD About the OECD The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is a forum in which The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is a forum in which governments compare and exchange policy experiences, identify good practices in light of emerging governments compare and exchange policy experiences, identify good practices in light of emerging challenges, and promote decisions and recommendations to produce better policies for better lives. challenges, and promote decisions and recommendations to produce better policies for better lives. The OECD’s mission is to promote policies that improve economic and social well-being of people The OECD’s mission is to promote policies that improve economic and social well-being of people around the world. around the world. The OECD Champion Mayors initiative The OECD Champion Mayors initiative The OECD launched a global coalition of Champion Mayors for Inclusive Growth in March 2016, as part The OECD launched a global coalition of Champion Mayors for Inclusive Growth in March 2016, as part of the broader OECD Inclusive Growth initiative. The OECD approach to Inclusive Growth is multi- of the broader OECD Inclusive Growth initiative. The OECD approach to Inclusive Growth is multi- dimensional, going beyond income. Champion Mayors are a group of willing leaders who have dimensional, going beyond income. Champion Mayors are a group of willing leaders who have committed to tackling inequalities and promoting more inclusive economic growth in cities. For more committed to tackling inequalities and promoting more inclusive economic growth in cities. -

Download YAM011

yetanothermagazine filmtvmusic aug2010 lima film festival 2010 highlights blockbuster season from around the world in this yam we review // aftershocks, inception, toy story 3, the ghost writer, taeyang, se7en, boa, shinee, bibi zhou, jing chang, the derek trucks band, time of eve and more // yam exclusive interview with songwriter diane warren film We keep working on that, but there’s toy story 3 pg4 the ghost writer pg5 so much territory to cover, and so You know the address: aftershocks pg6 very little of us. This is why we need [email protected] inception pg7 lima film festival// yam contributors. We know our highlights pg9 readers are primarily located in the amywong // cover// US, but I’m hoping to get people yam exclusive from other countries to review their p.s.: I actually spoke to Diane interview with diane warren pg12 local releases. The more the merrier, Warren. She's like the soundtrack music people. of our lives, to anyone of my the derek trucks band - roadsongs pg16 generation anyway. Check it out. se7en - digital bounce pg16 shinee - lucifer pg17 Yup, we’re grovelling for taeyang - solar pg17 contributors. I’m particularly eminem - recovery pg18 macy gray - the sellout pg18 interested in someone who is jing chang - the opposite me pg18 located in New York, since we’ve bibi zhou - i.fish.light.mirror pg18 nick chou - first album pg19 received a couple of screening boa - hurricane venus pg19 invites, but we got no one there. tv Interested? Hit me up. bad guy pg20 time of eve pg20 books uso. -

![[Joongang Ilbo – Home&] a University Campus? No, It's an International School to Debut in Incheon](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8581/joongang-ilbo-home-a-university-campus-no-its-an-international-school-to-debut-in-incheon-258581.webp)

[Joongang Ilbo – Home&] a University Campus? No, It's an International School to Debut in Incheon

[JoongAng Ilbo – home&] A university campus? No, it’s an international school to debut in Incheon Tip: How does an international school differ from a foreign school? Chadwick International, which will open this fall, is an international school. To be more precise, it is a foreign educational institution, which differs from a foreign school. Unlike an international school, which will debut for the first time in the nation, there are some 20 foreign schools in Seoul alone. As for admission, an international school can accept local students up to 30% of its quota while a foreign school can only admit locals who have lived overseas for over three years. Also, a local school corporation is eligible to set up a foreign school while an international school is only established by a foreign education school corporation. A reporter visited Chadwick International, with a couple of experts specializing school architecture. A prestigious foreign private institution has finally arrived in Korea. And that is Chadwick International in Songdo International City that has been established, in accordance with “The Special Laws on Establishment and Operations of Foreign Educational Institution.” Its annual tuition fees reach more than KRW 30 million, and its unique building structure and design seems to be a grand preview of what to be offered. “The school has been designed to facilitate our primary education goal through the state-of-art facility features and carefully- customized classrooms for kids,” R. Warmington, President and CEO of Chadwick International, said. Most prestigious private education institutions stress that education starts from the very stage, at which a school building is designed, not from the school curriculum. -

The Conference Exhibitions

THE CONFERENCE EXHIBITIONS Successful Voyages, Sustainable Planet THE CONFERENCE EXHIBITIONS World Festival for all The 19th IALA Conference comprises a series of Companion Programme Industrial Expo & Fair Heritage Exhibition A Meaningful Legacy for the Future activities that bring members of IALA together to share their experiences in improving navigation safety through knowledge and innovation. This Incheon has established itself as a major transportation hub in Industrial EXPO & FAIR at the Conference covers a wider range of The Conference will open an cultural heritage exhibition of northeast Asia with the world-renowned Incheon International themes and exhibits - R&D, AtoN services, AtoN products, AIS, lighthouses. The exhibition will be co-organised with IALA edition of the Conference will consist of the Airport and Incheon Port. The transport system in Incheon is Monitoring as well as Energy sources and Power supply. national members with the aim to raise awareness of the THE CONFERENCE following events. very convenient. Gangnam District in Seoul, which inspired the importance of lighthouse heritage conservation. Council & General Assembly It will provide an ideal platform for industry leaders to meet, singer Psy's world famous song "Gangnam Style", is an easy Heritage exhibition will be one of the most notable events, Social Events network and share knowledge and experience. Companion Programme distance away. showcasing a wide-ranging display items concerned with lighthouses from all over the world. The companion programme involves three courses to popular Council and General Assembly places in the city and its suburbs. There will be two sessions of the IALA Council. The last ordinary Experience Programmes HERITAGE EXHIBITIONS session for the period 2014-2018 will be held, and the formation Incheon Declaration to Industrial EXPO & FAIR of the new Council will take place after the elections. -

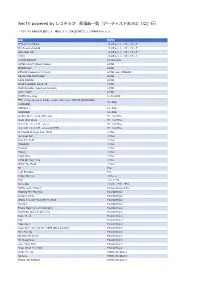

Rectv Powered by レコチョク 配信曲 覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」 )

RecTV powered by レコチョク 配信曲⼀覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」⾏) ※2021/7/19時点の配信曲です。時期によっては配信が終了している場合があります。 曲名 歌手名 アワイロサクラチル バイオレント イズ サバンナ It's Power of LOVE バイオレント イズ サバンナ OH LOVE YOU バイオレント イズ サバンナ つなぐ バイオレント イズ サバンナ I'M DIFFERENT HI SUHYUN AFTER LIGHT [Music Video] HYDE INTERPLAY HYDE ZIPANG (Japanese Version) HYDE feat. YOSHIKI BELIEVING IN MYSELF HYDE FAKE DIVINE HYDE WHO'S GONNA SAVE US HYDE MAD QUALIA [Japanese Version] HYDE LET IT OUT HYDE 数え切れないKiss Hi-Fi CAMP 雲の上 feat. Keyco & Meika, Izpon, Take from KOKYO [ACOUSTIC HIFANA VERSION] CONNECT HIFANA WAMONO HIFANA A Little More For A Little You ザ・ハイヴス Walk Idiot Walk ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン(ライヴ) ザ・ハイヴス If I Could Change Your Mind ハイム Summer Girl ハイム Now I'm In It ハイム Hallelujah ハイム Forever ハイム Falling ハイム Right Now ハイム Little Of Your Love ハイム Want You Back ハイム BJ Pile Lost Paradise Pile I Was Wrong バイレン 100 ハウィーD Shine On ハウス・オブ・ラヴ Battle [Lyric Video] House Gospel Choir Waiting For The Sun Powderfinger Already Gone Powderfinger (Baby I've Got You) On My Mind Powderfinger Sunsets Powderfinger These Days [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Stumblin' [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Take Me In Powderfinger Tail Powderfinger Passenger Powderfinger Passenger [Live At The 1999 ARIA Awards] Powderfinger Pick You Up Powderfinger My Kind Of Scene Powderfinger My Happiness Powderfinger Love Your Way Powderfinger Reap What You Sow Powderfinger Wake We Up HOWL BE QUIET fantasia HOWL BE QUIET MONSTER WORLD HOWL BE QUIET 「いくらだと思う?」って聞かれると緊張する(ハタリズム) バカリズムと アステリズム HaKU 1秒間で君を連れ去りたい HaKU everything but the love HaKU the day HaKU think about you HaKU dye it white HaKU masquerade HaKU red or blue HaKU What's with him HaKU Ice cream BACK-ON a day dreaming.. -

Choosing the Right Location Page 1 of 4 Choosing the Right Location

Choosing The Right Location Page 1 of 4 Choosing The Right Location Geography The Korean Peninsula lies in the north-eastern part of the Asian continent. It is bordered to the north by Russia and China, to the east by the East Sea and Japan, and to the west by the Yellow Sea. In addition to the mainland, South Korea comprises around 3,200 islands. At 99,313 sq km, the country is slightly larger than Austria. It has one of the highest population densities in the world, after Bangladesh and Taiwan, with more than 50% of its population living in the country’s six largest cities. Korea has a history spanning 5,000 years and you will find evidence of its rich and varied heritage in the many temples, palaces and city gates. These sit alongside contemporary architecture that reflects the growing economic importance of South Korea as an industrialised nation. In 1948, Korea divided into North Korea and South Korea. North Korea was allied to the, then, USSR and South Korea to the USA. The divide between the two countries at Panmunjom is one of the world’s most heavily fortified frontiers. Copyright © 2013 IMA Ltd. All Rights Reserved. Generated from http://www.southkorea.doingbusinessguide.co.uk/the-guide/choosing-the-right- location/ Tuesday, September 28, 2021 Choosing The Right Location Page 2 of 4 Surrounded on three sides by the ocean, it is easy to see how South Korea became a world leader in shipbuilding. Climate South Korea has a temperate climate, with four distinct seasons. Spring, from late March to May, is warm, while summer, from June to early September is hot and humid. -

Fenomén K-Pop a Jeho Sociokulturní Kontexty Phenomenon K-Pop and Its

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI PEDAGOGICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra hudební výchovy Fenomén k-pop a jeho sociokulturní kontexty Phenomenon k-pop and its socio-cultural contexts Diplomová práce Autorka práce: Bc. Eliška Hlubinková Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Filip Krejčí, Ph.D. Olomouc 2020 Poděkování Upřímně děkuji vedoucímu práce Mgr. Filipu Krejčímu, Ph.D., za jeho odborné vedení při vypracovávání této diplomové práce. Dále si cením pomoci studentů Katedry asijských studií univerzity Palackého a členů české k-pop komunity, kteří mi pomohli se zpracováním tohoto tématu. Děkuji jim za jejich profesionální přístup, rady a celkovou pomoc s tímto tématem. Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně s použitím uvedené literatury a dalších informačních zdrojů. V Olomouci dne Podpis Anotace Práce se zabývá hudebním žánrem k-pop, historií jeho vzniku, umělci, jejich rozvojem, a celkovým vlivem žánru na společnost. Snaží se přiblížit tento styl, který obsahuje řadu hudebních, tanečních a kulturních směrů, široké veřejnosti. Mimo samotnou podobu a historii k-popu se práce věnuje i temným stránkám tohoto fenoménu. V závislosti na dostupnosti literárních a internetových zdrojů zpracovává historii žánru od jeho vzniku až do roku 2020, spolu s tvorbou a úspěchy jihokorejských umělců. Součástí práce je i zpracování dvou dotazníků. Jeden zpracovává názor české veřejnosti na k-pop, druhý byl mířený na českou k-pop komunitu a její myšlenky ohledně tohoto žánru. Abstract This master´s thesis is describing music genre k-pop, its history, artists and their own evolution, and impact of the genre on society. It is also trying to introduce this genre, full of diverse music, dance and culture movements, to the public. -

Stardigio Program

スターデジオ チャンネル:408 J-POPピックアップアーティスト 放送日:2021/06/28~2021/07/04 「番組案内 (8時間サイクル)」 開始時間:4:00〜/12:00〜/20:00〜 楽曲タイトル 演奏者名 ■DOBERMAN INFINITY 特集 INFINITY DOBERMAN INFINITY SAY YEAH!! DOBERMAN INFINITY Heartbeat DOBERMAN INFINITY x ELLY (三代目 J Soul Brothers from EXILE TRIBE) JUMP AROUND ∞ DOBERMAN INFINITY いつか DOBERMAN INFINITY GA GA SUMMER DOBERMAN INFINITY D.Island DOBERMAN INFINITY feat. m-flo あの日のキミと今の僕に DOBERMAN INFINITY SUPER BALL DOBERMAN INFINITY YOU & I DOBERMAN INFINITY We are the one DOBERMAN INFINITY 6 -Six- DOBERMAN INFINITY konomama DOBERMAN INFINITY Who the KING? DOBERMAN INFINITY ■FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE 特集 OVER DRIVE FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE Flying Fish FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE Believe in Love FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE Dear Destiny FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE Every moment FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE ターミナル FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE Time Camera FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE FANTASTIC 9 FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE Hey, darlin' FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE Winding Road ~未来へ~ FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE High Fever FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE STOP FOR NOTHING FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE Play Back FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE M.V.P. FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE ■THE RAMPAGE from EXILE TRIBE 特集(1) FIND A WAY THE RAMPAGE from EXILE TRIBE Lightning THE RAMPAGE from EXILE TRIBE ELEVATION THE RAMPAGE from EXILE TRIBE GO ON THE RAMPAGE THE RAMPAGE from EXILE TRIBE FRONTIERS THE RAMPAGE from EXILE TRIBE Knocking Knocking THE RAMPAGE from EXILE TRIBE Dirty Disco THE RAMPAGE from EXILE TRIBE Shangri-La THE RAMPAGE from EXILE TRIBE 100degrees