Signaling Aggression

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Man Meets Dog Konrad Lorenz 144 Pages Konrad Z

a How, why and when did man meet dog and cat? How much are they in fact guided by instinct, and what sort of intelligence have they? What is the nature of their affection or attachment to the human race? Professor Lorenz says that some dogs are descended from wolves and some from jackals, with strinkingly different results in canine personality. These differences he explains in a book full of entertaining stories and reflections. For, during the course of a career which has brought him world fame as a scientist and as the author of the best popular book on animal behaviour, King Solomon's Ring, the author has always kept and bred dogs and cats. His descriptions of dogs 'with a conscience', dogs that 'lie', and the fallacy of the 'false cat' are as amusing as his more thoughtful descriptions of facial expressions in dogs and cats and their different sorts of loyalty are fascinating. "...this gifted and vastly experiences naturalist writes with the rational sympathy of the true animal lover. He deals, in an entertaining, anectdotal way, with serious problems of canine behaviour." The Times Educational Supplement "...an admirable combination of wisdom and wit." Sunday Observer Konrad Lorenz Man Meets Dog Konrad Lorenz 144 Pages Konrad Z. Lorenz, born in 1903 in Vienna, studied Medicine and Biology. Rights Sold: UK/USA, France, In 1949, he founded the Institute for Comparative Behaviourism in China (simplified characters), Italy, Altenberg (Austria) and changed to the Max-Planck-Institute in 1951. Hungary, Romania, Korea, From 1961 to 1973, he was director of Max-Planck-Institute for Ethology Slovakia, Spain, Georgia, Russia, in Seewiesen near Starnberg. -

On the Aggression Diffusion Modeling and Minimization in Online Social

On the Aggression Diffusion Modeling and Minimization in Twitter MARINOS POIITIS, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece ATHENA VAKALI, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece NICOLAS KOURTELLIS, Telefonica Research, Spain Aggression in online social networks has been studied mostly from the perspective of machine learning which detects such behavior in a static context. However, the way aggression diffuses in the network has received little attention as it embeds modeling challenges. In fact, modeling how aggression propagates from one user to another, is an important research topic since it can enable effective aggression monitoring, especially in media platforms which up to now apply simplistic user blocking techniques. In this paper, we address aggression propagation modeling and minimization in Twitter, since it is a popular microblogging platform at which aggression had several onsets. We propose various methods building on two well-known diffusion models, Independent Cascade (퐼퐶) and Linear Threshold (!) ), to study the aggression evolution in the social network. We experimentally investigate how well each method can model aggression propagation using real Twitter data, while varying parameters, such as seed users selection, graph edge weighting, users’ activation timing, etc. It is found that the best performing strategies are the ones to select seed users with a degree-based approach, weigh user edges based on their social circles’ overlaps, and activate users according to their aggression levels. We further employ the best performing models to predict which ordinary real users could become aggressive (and vice versa) in the future, and achieve up to 퐴*퐶=0.89 in this prediction task. Finally, we investigate aggression minimization by launching competitive cascades to “inform” and “heal” aggressors. -

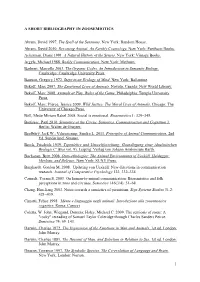

1 a SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY in ZOOSEMIOTICS Abram, David

A SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY IN ZOOSEMIOTICS Abram, David 1997. The Spell of the Sensuous. New York: Random House. Abram, David 2010. Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology. New York: Pantheon Books. Ackerman, Diane 1991. A Natural History of the Senses. New York: Vintage Books. Argyle, Michael 1988. Bodily Communication. New York: Methuen. Barbieri, Marcello 2003. The Organic Codes. An Introduction to Semantic Biology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Bateson, Gregory 1972. Steps to an Ecology of Mind. New York: Ballantine. Bekoff, Marc 2007. The Emotional Lives of Animals. Novato, Canada: New World Library. Bekoff, Marc 2008. Animals at Play. Rules of the Game. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Bekoff, Marc; Pierce, Jessica 2009. Wild Justice: The Moral Lives of Animals. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Böll, Mette Miriam Rakel 2008. Social is emotional. Biosemiotics 1: 329–345. Bouissac, Paul 2010. Semiotics at the Circus. Semiotics, Communication and Cognition 3. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. Bradbury, Jack W.; Vehrencamp, Sandra L. 2011. Principles of Animal Communication, 2nd Ed. Sunderland: Sinauer. Brock, Friedrich 1939. Typenlehre und Umweltforschung: Grundlegung einer idealistischen Biologie (= Bios vol. 9). Leipzig: Verlag von Johann Ambrosium Barth. Buchanan, Brett 2008. Onto-ethologies: The Animal Environments of Uexküll, Heidegger, Merleau, and Deleuze. New York: SUNY Press. Burghardt, Gordon M. 2008. Updating von Uexküll: New directions in communication research. Journal of Comparative Psychology 122, 332–334. Carmeli, Yoram S. 2003. On human-to-animal communication: Biosemiotics and folk perceptions in zoos and circuses. Semiotica 146(3/4): 51–68. Chang, Han-liang 2003. Notes towards a semiotics of parasitism. Sign Systems Studies 31.2: 421–439. -

Controlled Animals

Environment and Sustainable Resource Development Fish and Wildlife Policy Division Controlled Animals Wildlife Regulation, Schedule 5, Part 1-4: Controlled Animals Subject to the Wildlife Act, a person must not be in possession of a wildlife or controlled animal unless authorized by a permit to do so, the animal was lawfully acquired, was lawfully exported from a jurisdiction outside of Alberta and was lawfully imported into Alberta. NOTES: 1 Animals listed in this Schedule, as a general rule, are described in the left hand column by reference to common or descriptive names and in the right hand column by reference to scientific names. But, in the event of any conflict as to the kind of animals that are listed, a scientific name in the right hand column prevails over the corresponding common or descriptive name in the left hand column. 2 Also included in this Schedule is any animal that is the hybrid offspring resulting from the crossing, whether before or after the commencement of this Schedule, of 2 animals at least one of which is or was an animal of a kind that is a controlled animal by virtue of this Schedule. 3 This Schedule excludes all wildlife animals, and therefore if a wildlife animal would, but for this Note, be included in this Schedule, it is hereby excluded from being a controlled animal. Part 1 Mammals (Class Mammalia) 1. AMERICAN OPOSSUMS (Family Didelphidae) Virginia Opossum Didelphis virginiana 2. SHREWS (Family Soricidae) Long-tailed Shrews Genus Sorex Arboreal Brown-toothed Shrew Episoriculus macrurus North American Least Shrew Cryptotis parva Old World Water Shrews Genus Neomys Ussuri White-toothed Shrew Crocidura lasiura Greater White-toothed Shrew Crocidura russula Siberian Shrew Crocidura sibirica Piebald Shrew Diplomesodon pulchellum 3. -

The Ethological Approach to Aggression1

Psychological Medicine, 1980,10, 607-609 Printed in Great Britain EDITORIAL The ethological approach to aggression1 There are several ways in which ethology, the biological study of behaviour, can contribute to our understanding of aggression. First of all, by studying animals we can get some idea of what aggression is and how it relates to other, similar patterns of behaviour. We can also begin to grasp the reasons why natural selection has led to the widespread appearance of apparently destructive behaviour. To come to grips with this question requires the study of animals in their natural environment, for this is the environment to which they are adapted and only in it can the survival value of their behaviour be appreciated. By contrast, a final contribution of ethology, that of understanding the causal mechanisms underlying aggression, usually comes from work in the laboratory, for such research requires carefully controlled experiments. Ethology has shed light on all these topics, perhaps parti- cularly in the 15 years since Konrad Lorenz, one of the founding fathers of the discipline, discussed the subject in his book On Aggression. Lorenz's views were widely publicized and had great popular appeal: the fact that few ethologists agreed with what he said may explain why so many have since devoted time to studying aggression. The result, as I shall argue here, is that ethologists now have a much better insight into what aggression is, how it is caused and what functions it serves, and it is an insight sharply at odds with the ideas put forward by Lorenz. -

Mexico Chiapas 15Th April to 27Th April 2021 (13 Days)

Mexico Chiapas 15th April to 27th April 2021 (13 days) Horned Guan by Adam Riley Chiapas is the southernmost state of Mexico, located on the border of Guatemala. Our 13 day tour of Chiapas takes in the very best of the areas birding sites such as San Cristobal de las Casas, Comitan, the Sumidero Canyon, Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Tapachula and Volcan Tacana. A myriad of beautiful and sought after species includes the amazing Giant Wren, localized Nava’s Wren, dainty Pink-headed Warbler, Rufous-collared Thrush, Garnet-throated and Amethyst-throated Hummingbird, Rufous-browed Wren, Blue-and-white Mockingbird, Bearded Screech Owl, Slender Sheartail, Belted Flycatcher, Red-breasted Chat, Bar-winged Oriole, Lesser Ground Cuckoo, Lesser Roadrunner, Cabanis’s Wren, Mayan Antthrush, Orange-breasted and Rose-bellied Bunting, West Mexican Chachalaca, Citreoline Trogon, Yellow-eyed Junco, Unspotted Saw-whet Owl and Long- tailed Sabrewing. Without doubt, the tour highlight is liable to be the incredible Horned Guan. While searching for this incomparable species, we can expect to come across a host of other highlights such as Emerald-chinned, Wine-throated and Azure-crowned Hummingbird, Cabanis’s Tanager and at night the haunting Fulvous Owl! RBL Mexico – Chiapas Itinerary 2 THE TOUR AT A GLANCE… THE ITINERARY Day 1 Arrival in Tuxtla Gutierrez, transfer to San Cristobal del las Casas Day 2 San Cristobal to Comitan Day 3 Comitan to Tuxtla Gutierrez Days 4, 5 & 6 Sumidero Canyon and Eastern Sierra tropical forests Day 7 Arriaga to Mapastepec via the Isthmus of Tehuantepec Day 8 Mapastepec to Tapachula Day 9 Benito Juarez el Plan to Chiquihuites Day 10 Chiquihuites to Volcan Tacana high camp & Horned Guan Day 11 Volcan Tacana high camp to Union Juarez Day 12 Union Juarez to Tapachula Day 13 Final departures from Tapachula TOUR MAP… RBL Mexico – Chiapas Itinerary 3 THE TOUR IN DETAIL… Day 1: Arrival in Tuxtla Gutierrez, transfer to San Cristobal del las Casas. -

Highlights of the Museum of Zoology Highlights on the Blue Route

Highlights of the Museum of Zoology Highlights on the Blue Route Ray-finned Fishes 1 The ray-finned fishes are the most diverse group of backboned animals alive today. From the air-breathing Polypterus with its bony scales to the inflated porcupine fish covered in spines; fish that hear by picking up sounds with the swim bladder and transferring them to the ear along a series of bones to the electrosense of mormyrids; the long fins of flying fish helping them to glide above the ocean surface to the amazing camouflage of the leafy seadragon… the range of adaptations seen in these animals is extraordinary. The origin of limbs 2 The work of Prof Jenny Clack (1947-2020) and her team here at the Museum has revolutionised our understanding of the origin of limbs in vertebrates. Her work on the Devonian tetrapods Acanthostega and Ichthyostega showed that they had eight fingers and seven toes respectively on their paddle-like limbs. These animals also had functional gills and other features that suggest that they were aquatic. More recent work on early Carboniferous sites is shedding light on early vertebrate life on land. LeatherbackTurtle, Dermochelys coriacea 3 Leatherbacks are the largest living turtles. They have a wide geographical range, but their numbers are falling. Eggs are laid on tropical beaches, and hatchlings must fend for themselves against many perils. Only around one in a thousand leatherback hatchlings reach adulthood. With such a low survival rate, the harvesting of turtle eggs has had a devastating impact on leatherback populations. Nile Crocodile, Crocodylus niloticus 4 This skeleton was collected by Dr Hugh Cott (1900- 1987). -

Animal Conflict "1,

ANIMAL CONFLICT "1, ...... '", .. r.", . r ",~ Illustrated by Leslie M. Downie Department of Zoology, University of Glasgow ANIMAL CONFLICT Felicity A. Huntingford and Angela K. Turner Department of Zoology, University of Glasgow .-~ ' ..... '. .->, I , f . ~ :"fI London New York CHAPMAN AND HALL Chapman and Hall Animal Behaviour Series SERIES EDITORS D.M. Broom Colleen Macleod Professor of Animal Welfare, University of Cambridge, UK P.W. Colgan Professor of Biology, Queen's University, Canada Detailed studies of behaviour are important in many areas of physiology, psychology, zoology and agriculture. Each volume in this series will provide a concise and readable account of a topic of fundamental importance and current interest in animal behaviour, at a level appropriate for senior under graduates and research workers. Many facets of the study ofanimal behaviour will be explored and the topics included will reflect the broad scope of the subject. The major areas to be covered will range from behavioural ecology and sociobiology to general behavioural mechanisms and physiological psychology. Each volume will provide a rigorous and balanced view of the subject although authors will be given the freedom to develop material in their own way. To Tim) Joan and Jessica) with thanks) and to all the children who provided inspiration First published in 1987 by Chapmatl and Hall Ltd 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Published in the USA by Chapman atld Hall 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 © 1987 Felicity A. Huntingford and Angela K. Turner Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1987 ISBN -13: 978-94-010-9008-7 This title is available in both hardbound and paperback editions. -

Spatial Ecology of the Oregon Gartersnake, Thamnophis Atratus Hydrophilus, in a Free-Flowing Stream Environment

Copeia 2010, No. 1, 75–85 Spatial Ecology of the Oregon Gartersnake, Thamnophis atratus hydrophilus, in a Free-Flowing Stream Environment Hartwell H. Welsh, Jr.1, Clara A. Wheeler1, and Amy J. Lind2 Spatial patterns of animals have important implications for population dynamics and can reveal other key aspects of a species’ ecology. Movements and the resulting spatial arrangements have fitness and genetic consequences for both individuals and populations. We studied the spatial and dispersal patterns of the Oregon Gartersnake, Thamnophis atratus hydrophilus, using capture–recapture techniques. Snakes showed aggregated dispersion. Frequency distributions of movement distances were leptokurtic; the degree of kurtosis was highest for juvenile males and lowest for adult females. Males were more frequently recaptured at locations different from their initial capture sites, regardless of age class. Dispersal of neonates was not biased, whereas juvenile and adult dispersal were male-biased, indicating that the mechanisms that motivate individual movements differed by both age class and sex. Males were recaptured within shorter time intervals than females, and juveniles were recaptured within shorter time intervals than adults. We attribute differences in capture intervals to higher detectability of males and juveniles, a likely consequence of their greater mobility. The aggregated dispersion appears to be the result of multi-scale habitat selection, and is consistent with the prey choices and related foraging strategies exhibited by the different age classes. Inbreeding avoidance in juveniles and mate-searching behavior in adults may explain the observed male-biased dispersal patterns. ULTIPLE interacting factors may affect the resources such as food, basking sites, hibernacula or mates movements and resulting spatial patterns of (Gregory et al., 1987). -

Geographic Variation in Rock Wren (Salpinctes Obsoletus) Song Complexity

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Dissertations Student Research 8-2018 Geographic Variation in Rock Wren (Salpinctes Obsoletus) Song Complexity Nadje Amal Najar Follow this and additional works at: https://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Najar, Nadje Amal, "Geographic Variation in Rock Wren (Salpinctes Obsoletus) Song Complexity" (2018). Dissertations. 514. https://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations/514 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © 2018 NADJE AMAL NAJAR ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School GEOGRAPHIC VARIATION IN ROCK WREN (SALPINCTES OBSOLETUS) SONG COMPLEXITY A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Nadje Amal Najar College of Natural and Health Sciences School of Biological Sciences Biological Education August 2018 This Dissertation by: Nadje Amal Najar Entitled: Geographic variation in rock wren (Salpinctes obsoletus) song complexity has been approved as meeting the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Natural and Health Sciences in the School of Biological Sciences, Program of Biological Education. Accepted by the Doctoral Committee -

Phylogenetic Relationships of Terrestrial Australo-Papuan Elapid Snakes (Subfamily Hydrophiinae) Based on Cytochrome B and 16S Rrna Sequences J

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Vol. 10, No. 1, August, pp. 67–81, 1998 ARTICLE NO. FY970471 Phylogenetic Relationships of Terrestrial Australo-Papuan Elapid Snakes (Subfamily Hydrophiinae) Based on Cytochrome b and 16S rRNA Sequences J. Scott Keogh,*,†,1 Richard Shine,* and Steve Donnellan† *School of Biological Sciences A08, University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales 2006, Australia; and †Evolutionary Biology Unit, South Australian Museum, North Terrace, Adelaide, South Australia 5000, Australia Received April 24, 1997; revised September 4, 1997 quence data support many of the conclusions reached Phylogenetic relationships among the venomous Aus- by earlier studies using other types of data, but addi- tralo-Papuan elapid snake radiation remain poorly tional information will be needed before the phylog- resolved, despite the application of diverse data sets. eny of the Australian elapids can be fully resolved. To examine phylogenetic relationships among this 1998 Academic Press enigmatic group, portions of the cytochrome b and 16S Key Words: mitochondrial DNA; cytochrome b; 16S rRNA mitochondrial DNA genes were sequenced from rRNA; reptile; snake; elapid; sea snake; Australia; New 19 of the 20 terrestrial Australian genera and 6 of the 7 Guinea; Pacific; Asia; biogeography. terrestrial Melanesian genera, plus a sea krait (Lati- cauda) and a true sea snake (Hydrelaps). These data clarify several significant issues in elapid phylogeny. First, Melanesian elapids form sister groups to Austra- INTRODUCTION lian species, indicating that the ancestors of the Austra- lian radiation came via Asia, rather than representing The diverse, cosmopolitan, and medically important a relict Gondwanan radiation. Second, the two major elapid snakes are a monophyletic clade of approxi- groups of sea snakes (sea kraits and true sea snakes) mately 300 species and 61 genera (Golay et al., 1993) represent independent invasions of the marine envi- primarily defined by their unique venom delivery sys- ronment. -

21 Sep 2018 Lists of Victims and Hosts of the Parasitic

version: 21 Sep 2018 Lists of victims and hosts of the parasitic cowbirds (Molothrus). Peter E. Lowther, Field Museum Brood parasitism is an awkward term to describe an interaction between two species in which, as in predator-prey relationships, one species gains at the expense of the other. Brood parasites "prey" upon parental care. Victimized species usually have reduced breeding success, partly because of the additional cost of caring for alien eggs and young, and partly because of the behavior of brood parasites (both adults and young) which may directly and adversely affect the survival of the victim's own eggs or young. About 1% of all bird species, among 7 families, are brood parasites. The 5 species of brood parasitic “cowbirds” are currently all treated as members of the genus Molothrus. Host selection is an active process. Not all species co-occurring with brood parasites are equally likely to be selected nor are they of equal quality as hosts. Rather, to varying degrees, brood parasites are specialized for certain categories of hosts. Brood parasites may rely on a single host species to rear their young or may distribute their eggs among many species, seemingly without regard to any characteristics of potential hosts. Lists of species are not the best means to describe interactions between a brood parasitic species and its hosts. Such lists do not necessarily reflect the taxonomy used by the brood parasites themselves nor do they accurately reflect the complex interactions within bird communities (see Ortega 1998: 183-184). Host lists do, however, offer some insight into the process of host selection and do emphasize the wide variety of features than can impact on host selection.