Highway Boondoggles 6 Big Projects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interstate 11 Update

Management Comm ittee Maricopa Association of Governments June 9, 2010 Interstate 11 Update © 2010, All Rights Reserved. 1 Bordering States COG/MPO DISCUSSIONS TiTourism and RRtiecreation . GEORGE:ST . GEORGE:ST Scottsdale of Utah? California California Las Las Navajjj o Nation relates Population: Population:Vegas Vegas Grand Canyon more to New Mexico TOURISM TOURISM 60 M60 M by 2050!by 2050! 1717 II --1717 2525 High-tech High -tech Bedroom Bedroom Extension? Extension? communitycommunity community community industry along II --2525 People People Businesses Businesses Eager/ Springerville Second homes provide shopping/ services to Western New ECONOMIC DE Tourists Tourists Mexico Mexico Commercial Vehicles agriculture agriculture V Mexico’s fastest ELOPMENT growing states are in the north (Sonora, Chihuahua, and Nuevo Leon) Leon) Keyyy CONNECTIONS to Guaymas, Hermosillo, Punta Colonet maquiladoras Proposed Interstate 11 Corridor © 2010, All Rights Reserved. 2 Arizona Arizona COG/MPO DISCUSSIONS .. Commercial Trucking .. Distribution throughout Southwest USA R e c r e a t i o n .. Elevation in Central Arizona (SR(SR--89/SR89/SR--69)69) Pearce Pearce Growth Growth .. USUS--95/SR95/SR--95 Corridor95 Corridor Ferry Ferry Limitations CANAMEX.. CANAMEX .. Natural Resources .. Copper in Safford Area InIn-- .. Emerging Industries rn rn EX?EX? migggration eeee .. Welton Oil Refinery MMMM Warehousing.. Warehousing WestWest CANACANA .. Sun Corridor Megaregion Population Prescott.. Prescott will double Copppper pp mining mining Phoenix.. Phoenix Tucson.. Tucson Agrarian Agrarian Industrial Industrial .. Recreation and Tourism Incoming Incoming Informal Truck Bypasses Commerce! Warehousing/Distribution Hub Proposed Interstate 11 Corridor © 2010, All Rights Reserved. 3 2006 Tonnage of TrailerTrailer--onon--FlatcarFlatcar and ContainerContainer--onon--FlatcarFlatcar Intermodal Moves Proposed Interstate 11 Corridor © 2010, All Rights Reserved. -

Patriot Hills of Dallas

Patriot Hills of Dallas Background: After years of planning and market research our team assembled over 200+ - acres of prime Dallas property that was comprised of 8 separate properties. There is no record of any construction every being built on any of the 200 acres other than a homestead cabin. Much of the property was part of a family ranch used for grazing which is now overgrown with cedar and other species of trees and native grasses. Location: View property in the Dallas metroplex is one of the most unique features unmatched in the entire Dallas Fort Worth area. Most of the property is on a high bluff 100 feet above the surrounding area overlooking the Dallas Baptist University and the skyline of Fort Worth 21+ miles to the west. Convenient access to the greater Fort Worth and Dallas area by Interstate 20 and Interstate 30 Via Spur 408 freeways, Interstate 35, freeway 74, and the property is currently served by DART bus stops which provide connections to other mass transit options. The property is located 2 miles north of freeway 20 on the Spur 408 freeway and W. Kiest Blvd within the Dallas city limits. The property fronts on the East side of the Spur 408 freeway from Kiest Blvd exit on the North and runs continuous to the South to Merrifield Rd exit. The City of Dallas has plans to extend this road straight east to connect to West Ledbetter Drive that will take you directly to the Dallas Executive Airport and connecting on east with Freeway 67, Interstate 35 and Interstate 45. -

Transportation

visionHagerstown 2035 5 | Transportation Transportation Introduction An adequate vehicular circulation system is vital for Hagerstown to remain a desirable place to live, work, and visit. Road projects that add highway capacity and new road links will be necessary to meet the Comprehensive Plan’s goals for growth management, economic development, and the downtown. This chapter addresses the City of Hagerstown’s existing transportation system and establishes priorities for improvements to roads, transit, and pedestrian and bicycle facilities over the next 20 years. Goals 1. The city’s transportation network, including roads, transit, and bicycle and pedestrian facilities, will meet the mobility needs of its residents, businesses, and visitors of all ages, abilities, and socioeconomic backgrounds. 2. Transportation projects will support the City’s growth management goals. 3. Long-distance traffic will use major highways to travel around Hagerstown rather than through the city. Issues Addressed by this Element 1. Hagerstown’s transportation network needs to be enhanced to maintain safe and efficient flow of people and goods in and around the city. 2. Hagerstown’s network of major roads is generally complete, with many missing or partially complete segments in the Medium-Range Growth Area. 3. Without upgrades, the existing road network will not be sufficient to accommodate future traffic in and around Hagerstown. 4. Hagerstown’s transportation network needs more alternatives to the automobile, including transit and bicycle facilities and pedestrian opportunities. Existing Transportation Network Known as “Hub City,” Hagerstown has long served as a transportation center, first as a waypoint on the National Road—America’s first Dual Highway (US Route 40) federally funded highway—and later as a railway node. -

Highway Boondoggles 6 Big Projects

HIGHWAY BOONDOGGLES 6 Big Projects. Bigger Price Tags. Limited Benefits. HIGHWAY BOONDOGGLES 6 Big Projects. Bigger Price Tags. Limited Benefits. WRITTEN BY: GIDEON WEISSMAN AND BRYN HUXLEY-REICHER FRONTIER GROUP MATTHEW CASALE AND JOHN STOUT U.S. PIRG EDUCATION FUND DECEMBER 2020 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors wish to thank Kevin Brubaker of Environmental Law & Policy Center, Clint Richmond of Massachusetts Sierra Club, Chris DeScherer and Sarah Stokes of Southern En- vironmental Law Center, Wendy Landman of WalkBoston, Jenna Stevens of Environment Florida, Ben Hellerstein of Environment Massachusetts, Abe Scarr of Illinois PIRG and Bay Scoggin of TexPIRG for their review of drafts of this document, as well as their insights and suggestions. Thanks also to Frontier Group interns Christiane Paulhus and Hannah Scholl, and Susan Rakov, Tony Dutzik, David Lippeatt and Adrian Pforzheimer of Frontier Group for editorial support. The authors bear responsibility for any factual errors. Policy recommendations are those of NCPIRG Education Fund. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders or those who provided review. Project maps included in this report should be considered approximations based on publicly avail- able information and not used for planning purposes. 2020 NCPIRG Education Fund. Some Rights Reserved. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 3.0 Unported License. To view the terms of this license, visit creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0. With public debate around important issues often dominated by special interests pursu- ing their own narrow agendas, NCPIRG Education Fund offers an independent voice that works on behalf of the public interest. -

90000 SF Warehouse Building with 80000 SF Available

90,000 SF warehouse building with 80,000 SF available for lease. Existing tenant in remaining 10,000 SF. Property is located in the Valmont Industrial Park, 1.5 miles from Route I-81 & 10 miles from Route I-80. LATITUDE: 40.971340 LONGITUDE: -76.018204 90,000 SF+/- Building PIN: T7S7001025-63 7+/- Acres Public Utilities Block/Brick Exterior Flat Roof Concrete and Tile Floors 20 ft. Ceilings 480v, 600 amp Electric 6 Dock High Doors 1 Ground Level Drive-In Door 2 Tailgate Doors 40’ x 50’ Column Spacing Fluorescent Lighting Wet Sprinkler System Paved Parking for 46 Vehicles Zoned M-2 (Manufacturing) 2019 Taxes - $32,413 Al Guari, Vice President-Brokerage [email protected] Office: 570.823.1100 * Cell: 570.499.2889 1-800-894-8040 RPD Solutions www.rpdsolutions.com RPD Analyzer Detail Report with GIS Tax Map Luzerne County, PA Owner: 150 JAYCEE DRIVE ASSOCIATES LP PIN: T7S7001025-63 Owner2: Map: T7S7 Address: PO BOX 160 Township: WEST HAZLETON BOROUGH 63 ST PETERS PA 19470 Dev Desc: Prop Addr: 150 JAYCEE DR School Dist: Hazelton Area Gen Desc: 1 S COMM BLDG Land Use: Other Furniture and Fixtures-Manufacturing (2590) Deed Date: 04/10/2008 Land Asmt: $200,000 Section: Acreage: 7.0 Deed Book: 3008 Bldg Asmt: $1,350,000 Block: 001 Layout: Deed Page: 81400 Total Asmt: $1,550,000 Lot: 025 Zoning: Sale Date: 04/10/2008 School Tax: Year Built: Prop Class: Taxable Sale Price: $2,500,000 Twp Tax: Sq Ft: Structure: Type: Building Total Tax: $32,413 Stories: Style: Control #: 63-2-571-D11-7 Water: Loan Date 1: Ward Desc: 02 Sewer: Amount 1: Owner Class: Utility: Loan Type 1: Living Units: Heat Type: Rate Type 1: Condition: Heat Fuel: Int Rate 1: Road: Air Cond: Holder 1: Frontage: Depth: Total Rms: Tax Rate: Garage: Bedrooms: Tax Ratio: Attic: Full Baths: Other 1: Basement: Half Baths: Fireplaces: Kitchens: Other 2: Pool: Family Rms: Note: Image NOT a Complete Tax Map .. -

FHWA AMRP FY 2020 Enacted.Pdf

United States Department of Transportation FY 2020 Annual Modal Research Plans Federal Highway Administration May 1, 2019 Nicole Nason Administrator Contents Executive Summary.............................................................................................................................................. 2 Chapter 1: Introduction/Agency‐Wide Research Approach ................................................................ 8 Chapter 2. High Priority Project Descriptions ........................................................................................ 16 Chapter 3 ‐ FY 2020 Program Descriptions ............................................................................................. 34 Chapter 4 – FY 2021 Program Descriptions .......................................................................................... 250 FHWA FY2020‐FY2021 AMRP– March 2019 Page 1 Executive Summary The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) addresses current issues and emerging challenges, creates efficiencies in the highway and transportation sector, and provides information to support policy decisions through its Research and Technology (R&T) programs. FHWA conducts advanced and applied research; coordinates and collaborates with other research organizations, both nationally and internationally, to leverage knowledge; and develops and delivers solutions to address highway transportation needs. FHWA is uniquely positioned to identify and address highway issues of national significance and build effective partnerships that leverage and -

Proposed Project – I-35 Improvements

I‐35 ROADWAY Proposed Project – I‐35 Improvements Existing Facility The majority of existing I‐35 between the Williamson/Bell County Line and Hillsboro is four lanes, with six‐lane sections in Waco, Temple, and the southern part of Bell County. Project Purpose The purpose of the proposed project is to increase capacity and improve mobility on I‐35. Project Proposed by Corridor Segment 2 Committee The I‐35 Corridor Segment 2 Committee is considering improvements to I‐35, which would involve widening I‐35 to eight lanes from Hillsboro to the Williamso n/Bell County Line for a distance of approximately 93 miles. Conceptual Project Cost Estimate According to the TxDOT Waco District Improvement Plan, the cost for expanding I‐35 to six lanes through this area is estimated at approximately $1.5 billion. The six‐lane expansion of I‐35 is currently underway. The estimated cost for expanding I‐35 from six to eight lanes is between $2.25 billion and $3.25 billion, including design and construction. This cost, in 2010 dollars, does not include the purchase of right of way. The estimated project costs could increase due to right of way purchases and potential impacts to properties. I‐35 Corridor Segment 2 Committee www.MY35.org September 2010 I‐35 ROADWAY Proposed Project – I‐35E from I‐20 to Hillsboro Existing Facility The existing I‐35E facility is four lanes from Hillsboro to approximately ten miles south of I‐20, where it transitions to six and then eight lanes. Project Purpose The purpose of the proposed project is to increase capacity and improve overall mobility on I‐35E. -

Fort Worth Arlington

RealReal EstateEstate MarketMarket OverviewOverview FortFort Worth-ArlingtonWorth-Arlington Jennifer S. Cowley Assistant Research Scientist Texas A&M University July 2001 © 2001, Real Estate Center. All rights reserved. RealReal EstateEstate MarketMarket OverviewOverview FortFort Worth-ArlingtonWorth-Arlington Contents 2 Population 6 Employment 9 Job Market 10 Major Industries 11 Business Climate 13 Education 14 Transportation and Infrastructure Issues 15 Public Facilities 16 Urban Growth Patterns Map 1. Growth Areas 17 Housing 20 Multifamily 22 Manufactured Housing Seniors Housing 23 Retail Market 24 Map 2. Retail Building Permits 26 Office Market 28 Map 3. Office and Industrial Building Permits 29 Industrial Market 31 Conclusion RealReal EstateEstate MarketMarket OverviewOverview FortFort Worth-ArlingtonWorth-Arlington Jennifer S. Cowley Assistant Research Scientist Haslet Southlake Keller Grapevine Interstate 35W Azle Colleyville N Richland Hills Loop 820 Hurst-Euless-Bedford Lake Worth Interstate 30 White Settlement Fort Worth Arlington Interstate 20 Benbrook Area Cities Counties Arlington Haltom City Hood Bedford Hurst Johnson Benbrook Keller Parker Burleson Mansfield Tarrant Cleburne North Richland Hills Land Area of Fort Worth- Colleyville Saginaw Euless Southlake Arlington MSA Forest Hill Watauga 2,945 square miles Fort Worth Weatherford Grapevine White Settlement Population Density (2000) 578 people per square mile he Fort Worth-Arlington Metro- cane Harbor and The Ballpark at square-foot rodeo arena, and to the politan Statistical -

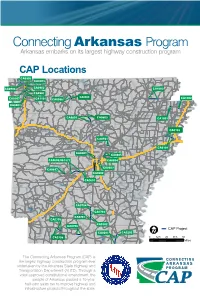

Arkansas Embarks on Its Largest Highway Construction Program

Connecting Arkansas Program Arkansas embarks on its largest highway construction program CAP Locations CA0905 CA0903 CA0904 CA0902 CA1003 CA0901 CA0909 CA1002 CA0907 CA1101 CA0906 CA0401 CA0801 CA0803 CA1001 CA0103 CA0501 CA0101 CA0603 CA0605 CA0606/061377 CA0604 CA0602 CA0607 CA0608 CA0601 CA0704 CA0703 CA0701 CA0705 CA0702 CA0706 CAP Project CA0201 CA0202 CA0708 0 12.5 25 37.5 50 Miles The Connecting Arkansas Program (CAP) is the largest highway construction program ever undertaken by the Arkansas State Highway and Transportation Department (AHTD). Through a voter-approved constitutional amendment, the people of Arkansas passed a 10-year, half-cent sales tax to improve highway and infrastructure projects throughout the state. Job Job Name Route County Improvements CA0101 County Road 375 – Highway 147 Highway 64 Crittenden Widening CA0103 Cross County Line - County Road 375 Highway 64 Crittenden Widening CA0201 Louisiana State Line – Highway 82 Highway 425 Ashley Widening CA0202 Highway 425 – Hamburg Highway 82 Ashley Widening CA0401 Highway 71B – Highway 412 Interstate 49 Washington Widening CA0501 Turner Road – County Road 5 Highway 64 White Widening CA0601 Highway 70 – Sevier Street Interstate 30 Saline Widening CA0602 Interstate 530 – Highway 67 Interstates 30/40 Pulaski Widening and Reconstruction CA0603 Highway 365 – Interstate 430 Interstate 40 Pulaski Widening CA0604 Main Street – Vandenberg Boulevard Highway 67 Pulaski Widening CA0605 Vandenberg Boulevard – Highway 5 Highway 67 Pulaski/Lonoke Widening CA0606 Hot Springs – Highway -

Greater OKLAHOMA CITY at a Glance

Greater OKLAHOMA CITY at a glance 123 Park Avenue | Oklahoma City, OK 73102 | 405.297.8900 | www.greateroklahomacity.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Location ................................................4 Economy .............................................14 Tax Rates .............................................24 Climate ..................................................7 Education ...........................................17 Utilities ................................................25 Population............................................8 Income ................................................21 Incentives ...........................................26 Transportation ..................................10 Labor Analysis ...................................22 Available Services ............................30 Housing ...............................................13 Commercial Real Estate .................23 Ranked No. 1 for Best Large Cities to Start a Business. -WalletHub 2 GREATER OKLAHOMA CITY: One of the fastest-growing cities is integral to our success. Our in America and among the top ten low costs, diverse economy and places for fastest median wage business-friendly environment growth, job creation and to start a have kept the economic doldrums business. A top two small business at bay, and provided value, ranking. One of the most popular stability and profitability to our places for millennials and one of companies – and now we’re the top 10 cities for young adults. poised to do even more. The list of reasons you should Let us introduce -

Transportation Asset Management Plan AC000225

2028 Puerto Rico Transportation Asset Management Plan AC000225 Final Revised October 8, 2019 Prepared by CMA Team for the Puerto Rico Highway and Transportation Authority 2028 PR Transportation Asset Management Plan Final Revised October 8, 2019 CMA Team is composed of: CMA Architects & Engineers LLC Team Page ii 2028 PR Transportation Asset Management Plan Final Revised October 8, 2019 Index Index ................................................................................................................................ i List of Figures ...............................................................................................................iv List of Tables ................................................................................................................vi Acronyms ........................................................................................................................ x Preface ............................................................................................................................xi Required Asset Management Processes .................................................................... xii Mandatory Condition Targets ..................................................................................... xiv Review of Processes, Investments, and Conditions ................................................... xiv The Start of a New Era ................................................................................................xv Organization of This Plan .......................................................................................... -

Chapter 1 North

Interstate 73 FEIS: I-95 to North Carolina The feasibility study recognized that there had been some improvements to roads in the project study area; however, the improved roads were predicted to have capacity problems along some segments by the year 2025, based on traffic modeling. Future traffic projections indicated that I-73 would divert traffic from existing roadways, which would improve capacity and reduce traffic congestion.10 North Carolina completed a feasibility study in 2005 that evaluated alternatives for the proposed I 74 in Columbus and Brunswick Counties, North Carolina, located in the southeastern portion of the state. The study was an initial step in the planning and design and described the project, costs, and identified potential problems that required consideration. The Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users (SAFETEA-LU) was passed by Congress and signed into law on August 10, 2005. SAFETEA-LU acknowledges the prior purpose for, and designation of, I-73 as a High Priority Corridor, along with designating it as a project of “national and regional significance” (23 U.S.C. §101(2005)). In addition, SAFETEA-LU provides earmarks for the I-73 project in South Carolina. At the state level, Concurrent Resolution H 3320 passed by the South Carolina General Assembly in 2003 states “that the members of the General Assembly express their collective belief and desire that the Department of Transportation should consider its next interstate project as one that provides the Pee Dee Region with access to the interstate system.”11 Both Congress and the South Carolina General Assembly have appropriated money to SCDOT to study the potential corridor for the proposed I-73.