The Maternal Gaze in the Gothic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12 Retina Gabriele K

299 12 Retina Gabriele K. Lang and Gerhard K. Lang 12.1 Basic Knowledge The retina is the innermost of three successive layers of the globe. It comprises two parts: ❖ A photoreceptive part (pars optica retinae), comprising the first nine of the 10 layers listed below. ❖ A nonreceptive part (pars caeca retinae) forming the epithelium of the cil- iary body and iris. The pars optica retinae merges with the pars ceca retinae at the ora serrata. Embryology: The retina develops from a diverticulum of the forebrain (proen- cephalon). Optic vesicles develop which then invaginate to form a double- walled bowl, the optic cup. The outer wall becomes the pigment epithelium, and the inner wall later differentiates into the nine layers of the retina. The retina remains linked to the forebrain throughout life through a structure known as the retinohypothalamic tract. Thickness of the retina (Fig. 12.1) Layers of the retina: Moving inward along the path of incident light, the individual layers of the retina are as follows (Fig. 12.2): 1. Inner limiting membrane (glial cell fibers separating the retina from the vitreous body). 2. Layer of optic nerve fibers (axons of the third neuron). 3. Layer of ganglion cells (cell nuclei of the multipolar ganglion cells of the third neuron; “data acquisition system”). 4. Inner plexiform layer (synapses between the axons of the second neuron and dendrites of the third neuron). 5. Inner nuclear layer (cell nuclei of the bipolar nerve cells of the second neuron, horizontal cells, and amacrine cells). 6. Outer plexiform layer (synapses between the axons of the first neuron and dendrites of the second neuron). -

The World Beautiful in Books TO

THE WORLD BEAUTIFUL IN BOOKS BY LILIAN WHITING Author of " The World Beautiful," in three volumes, First, Second, " " and Third Series ; After Her Death," From Dreamland Sent," " Kate Field, a Record," " Study of Elizabeth Barrett Browning," etc. If the crowns of the world were laid at my feet in exchange for my love of reading, 1 would spurn them all. — F^nblon BOSTON LITTLE, BROWN, AND COMPANY ^901 PL Copyright, 1901, By Little, Brown, and Company. All rights reserved. I\17^ I S ^ November, 1901 UNIVERSITY PRESS JOHN WILSON AND SON • CAMBRIDGE, U. S. A. Lilian SMIjttins'fii glMoriiB The World Beautiful. First Series The World Beautiful. Second Series The World Beautiful. Third Series After her Death. The Story of a Summer From Dreamland Sent, and Other Poems A Studv of Elizabeth Barrett Browning The Spiritual Significance Kate Field: a Record The World Beautiful in Books TO One whose eye may fall upon these pages; whose presence in tlie world of thought and achievement enriches life ; whose genius and greatness of spirit inspire my every day with renewed energy and faith, — this quest for " The World Beautiful" in literature is inscribed by LILIAN WHITING. " The consecration and the poeVs dream" CONTENTS. BOOK I. p,,. As Food for Life 13 BOOK II. Opening Golden Doors 79 BOOK III. The Rose of Morning 137 BOOK IV. The Chariot of the Soul 227 BOOK V. The Witness of the Dawn 289 INDEX 395 ; TO THE READER. " Great the Master And sweet the Magic Moving to melody- Floated the Gleam." |0 the writer whose work has been en- riched by selection and quotation from " the best that is known and thought in* the world," it is a special pleasure to return the grateful acknowledgments due to the publishers of the choice literature over whose Elysian fields he has ranged. -

Localisation of Visual Hallucinations

BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL 16 JULY 1977 147 of hypothermia; the duration of cardiac arrest; and the disturbances of sleep or consciousness.4 Hallucinations may be promptness and correctness of treatment. Peterson's pessi- evoked by sensory deprivation, but other factors are usually mistic report from California,8 in which all 15 near-drowned present; thus the "black-patch" delirium that may follow children who had fits, fixed dilated pupils, flaccidity, and loss cataract extraction in the elderly probably results from sensory Br Med J: first published as 10.1136/bmj.2.6080.147 on 16 July 1977. Downloaded from of pain sensation suffered severe anoxic encephalopathy, deprivation and mild senile brain changes and is more frequent may be explained by the high water temperatures there. In when hearing is also impaired.5 warm water the protective effect of hypothermia against brain Hallucinations may be due to focal lesions. Past experiences, damage would be missing. In contrast was the case described the quality of eidetic imagery, and psychodynamic "actors in Trondheim, Norway,9 in which a 5-year-old fell through influence the content of organic hallucinosis,6 and it would be ice in fresh water with an outside temperature of 10° below unwise to lean too heavily on the occurrence and nature of zero centigrade. He was in the water for 22 minutes and was hallucinosis in localising intracranial lesions. Visual hallucina- brought out apparently dead, with widely dilated pupils and tions are a relatively infrequent accompaniment oflesions ofthe bluish white skin. He was warmed up (the method was not calcarine cortex (Brodmann's area 17), which has few thalamo- described) and-despite the risks noted above-was given cortical connections; yet they may occur as a false-localising external cardiac massage without suffering ventricular symptom of frontal or subtentorial lesions. -

Camora 1.Pdf

The Function of the Rhetoric of Maternity in the Representation of Female Sexuality, Religion, Nationality, and Race in Early Modern English Literature and Culture by Cecilia Morales A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Schoenfeldt, Chair Dr. Neeraja Aravamudan, Edward Ginsberg Center, University of Michigan Professor Peggy McCracken Professor Catherine Sanok Professor Valerie Traub Cecilia Morales [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-7428-3777 © Cecilia Morales 2020 Acknowledgements Throughout my doctoral studies, I have been fortunate to have the love and support of countless individuals, to whom I owe a great deal of gratitude. I’d like to begin by thanking my committee members. Cathy and Peggy taught me valuable lessons not only about my work but about being a thoughtful and compassionate scholar and teacher. Valerie’s reminders to always be as generous as possible when discussing the work of other scholars has kept me sane and stable in this competitive world of academia. Mike helped me, a displaced Texan, to feel at home in Michigan from our first meeting, during which we chatted about both Shakespearean scholarship and Tex Mex. Finally, the most recent addition to my committee is Neeraja Aravamudan, who I consider my most active mentor and supporter. One of the best decisions I made during graduate school was accepting an internship at the Edward Ginsberg Center, where Neeraja became my supervisor. Neeraja and the other Ginsberg staff remind me it’s possible to take my work very seriously without taking myself too seriously. -

University of Birmingham Oscar Wilde, Photography, and Cultures Of

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Portal University of Birmingham Oscar Wilde, photography, and cultures of spiritualism Dobson, Eleanor License: None: All rights reserved Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Dobson, E 2020, 'Oscar Wilde, photography, and cultures of spiritualism: ''The most magical of mirrors''', English Literature in Transition 1880-1920, vol. 63, no. 2, pp. 139-161. Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Checked for eligibility 12/02/2019 Published in English Literature in Transition 1880-1920 http://www.eltpress.org/index.html General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. -

At the Mercy of Tiberius a Novel

AT THE MERCY OF TIBERIUS A NOVEL By AUGUSTA JANE EVANS AT THE MERCY OF TIBERIUS CHAPTER I. "You are obstinate and ungrateful. You would rather see me suffer and die, than bend your stubborn pride in the effort to obtain relief for me. You will not try to save me." The thin, hysterically unsteady voice ended in a sob, and the frail wasted form of the speaker leaned forward, as if the issue of life or death hung upon an answer. The tower clock of a neighboring church began to strike the hour of noon, and not until the echo of the last stroke had died away, was there a reply to the appeal. "Mother, try to be just to me. My pride is for you, not for myself. I shrink from seeing my mother crawl to the feet of a man, who has disowned and spurned her; I cannot consent that she should humbly beg for rights, so unnaturally withheld. Every instinct of my nature revolts from the step you require of me, and I feel as if you held a hot iron in your hand, waiting to brand me." "Your proud sensitiveness runs in a strange groove, and it seems you would prefer to see me a pauper in a Hospital, rather than go to your grandfather and ask for help. Beryl, time presses, and if I die for want of aid, you will be responsible; when it is too late, you will reproach yourself. If I only knew where and how to reach my dear boy, I should not importune you. -

Heritage-Statement

Document Information Cover Sheet ASITE DOCUMENT REFERENCE: WSP-EV-SW-RP-0088 DOCUMENT TITLE: Environmental Statement Chapter 6 ‘Cultural Heritage’: Final version submitted for planning REVISION: F01 PUBLISHED BY: Jessamy Funnell – WSP on behalf of PMT PUBLISHED DATE: 03/10/2011 OUTLINE DESCRIPTION/COMMENTS ON CONTENT: Uploaded by WSP on behalf of PMT. Environmental Statement Chapter 6 ‘Cultural Heritage’ ES Chapter: Final version, submitted to BHCC on 23rd September as part of the planning application. This document supersedes: PMT-EV-SW-RP-0001 Chapter 6 ES - Cultural Heritage WSP-EV-SW-RP-0073 ES Chapter 6: Cultural Heritage - Appendices Chapter 6 BSUH September 2011 6 Cultural Heritage 6.A INTRODUCTION 6.1 This chapter assesses the impact of the Proposed Development on heritage assets within the Site itself together with five Conservation Areas (CA) nearby to the Site. 6.2 The assessment presented in this chapter is based on the Proposed Development as described in Chapter 3 of this ES, and shown in Figures 3.10 to 3.17. 6.3 This chapter (and its associated figures and appendices) is not intended to be read as a standalone assessment and reference should be made to the Front End of this ES (Chapters 1 – 4), as well as Chapter 21 ‘Cumulative Effects’. 6.B LEGISLATION, POLICY AND GUIDANCE Legislative Framework 6.4 This section provides a summary of the main planning policies on which the assessment of the likely effects of the Proposed Development on cultural heritage has been made, paying particular attention to policies on design, conservation, landscape and the historic environment. -

Some Ads Are Hard to Swallow

< » g m jK S D A Y , SEPTEMBER 2, U k f w n f Daily Net ProH Run PAOI TWENTY J m thaWoak EMa« I 4l D. ■. lEnwing Iffralii Aarato 94,1944 on. Of th* **▼««*>*• FALL Bcandta Lodge, Order of two ■uooGMttt ISfOOO gr«nu 13,806 Vasa, will meet Umight at 8 to MAHRC to Get a_ VtofinMflV. Gosm coNcniT r a< the AMH About Town Orange Hall. Kuiper-Raesler in mnowiwr T- -» — . a , Batorday, B ^ 4, 7iB9 | «< rirnnlatlae 10-Year Renewal night, ths board will zoespL * SAI^AITON ARMY Manehattar^A City of VlUage Cborm Mr. «tid Mn. Frank Oallaa at Chapman Court. Order of quitclaim dead YOUTH CBNTIIR IM K Ukn St ara calebnlttnr Amaranth, will meet totnorrow Mias Ann Ratolar of Man' Of Bunce Lease haven Coro, to a plot ^ l ^ J M l Main Btroa* t)Mlr aotti waddinff annlveraany at -7:45 p.m. at the Masonic to Olaatoiuwry on wnlcn.roa V O L. LX X X IV , N O . 28B (EIOHTEBN PAQES) MANCHESTER, CONN., FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER S, 19M (OlMattM AArarifatog ee Page !•) PRICE SEVEN CHOU todanr. 1 % n have two chidran, oheater became the bride of J. town now oparataa a water 11m Keyatoaa ()nafto*| Templt. There will be a social The board of direotoro at lU TIm Ktog*a ■eTnatoa lOaa BUaaMth QaUaa, a mualc time after the meeting. Mrs. Randall Kulper of Wyckoff, N.J. taaebar to N«w York'City, and Neale MBler and a committee Saturday, Aug. 21 at the Wyck Tuesday night meeting wHl vote and OaiY Brant Joai^ OkHaa, a aUidmt at a 10-year renewal, 4t |1 per Donation |1 —. -

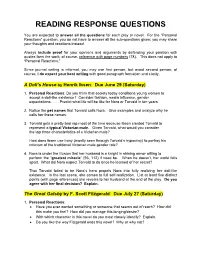

Reading Response Questions

READING RESPONSE QUESTIONS You are expected to answer all the questions for each play or novel. For the “Personal Reactions” question, you do not have to answer all the sub-questions given; you may share your thoughts and reactions instead. Always include proof for your opinions and arguments by defending your position with quotes form the work; of course, reference with page numbers (78). This does not apply to “Personal Reactions.” Since journal writing is informal, you may use first person, but avoid second person; of course, I do expect your best writing with good paragraph formation and clarity. A Doll’s House by Henrik IBsen: Due June 29 (Saturday) 1. Personal Reactions: Do you think that society today conditions young women to accept a doll-like existence? Consider fashion, media influence, gender expectations . Predict what life will be like for Nora or Torvald in ten years. 2. Notice the pet names that Torvald calls Nora. Give examples and analyze why he calls her these names. 3. Torvald gets a pretty bad rap most of the time because Ibsen created Torvald to represent a typical Victorian male. Given Torvald, what would you consider the top three characteristics of a Victorian male? How does Ibsen use irony (mostly seen through Torvald’s hypocrisy) to portray his criticism of the traditional Victorian male gender role? 4. Nora is under the illusion that her husband is a knight in shining armor willing to perform the “greatest miracle” (93, 112) if need be. When he doesn’t, her world falls apart. What did Nora expect Torvald to do once he learned of her secret? That Torvald failed to be Nora’s hero propels Nora into fully realizing her doll-like existence. -

Babylonian-Assyrian Birth-Omens and Their by Morris Jastrow 1

Babylonian-Assyrian Birth-Omens and Their by Morris Jastrow 1 Babylonian-Assyrian Birth-Omens and Their by Morris Jastrow The Project Gutenberg EBook of Babylonian-Assyrian Birth-Omens and Their Cultural Significance, by Morris Jastrow This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Babylonian-Assyrian Birth-Omens and Their Cultural Significance Author: Morris Jastrow Babylonian-Assyrian Birth-Omens and Their by Morris Jastrow 2 Release Date: April 9, 2011 [EBook #35791] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BABYLONIAN-ASSYRIAN BIRTH-OMENS *** Produced by Bryan Ness and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive.) Babylonian-Assyrian Birth-Omens And Their Cultural Significance by Morris Jastrow, jr. Ph. D. (Leipzig) Professor of Semitic Languages in the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia) Giessen 1914 Verlag von Alfred Toepelmann (vormals J. Ricker) =Religionsgeschichtliche Versuche und Vorarbeiten= begruendet von Albrecht Dieterich und Richard Wuensch herausgegeben von Richard Wuensch und Ludwig Deubner in Muenster i. W. in Koenigsberg i. Pr. XIV. Band. 5. Heft To SIR WILLIAM OSLER Regius Professor of Medicine Oxford University Babylonian-Assyrian Birth-Omens and Their -

Le Studio Hammer, Laboratoire De L'horreur Moderne

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 12 | 2016 Mapping gender. Old images ; new figures Conference Report: Le studio Hammer, laboratoire de l’horreur moderne Paris, (France), June 12-14, 2016 Conference organized by Mélanie Boissonneau, Gilles Menegaldo and Anne-Marie Paquet-Deyris David Roche Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/8195 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.8195 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference David Roche, “Conference Report: Le studio Hammer, laboratoire de l’horreur moderne ”, Miranda [Online], 12 | 2016, Online since 29 February 2016, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/miranda/8195 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.8195 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Conference Report: Le studio Hammer, laboratoire de l’horreur moderne 1 Conference Report: Le studio Hammer, laboratoire de l’horreur moderne Paris, (France), June 12-14, 2016 Conference organized by Mélanie Boissonneau, Gilles Menegaldo and Anne-Marie Paquet-Deyris David Roche 1 This exciting conference1 was the first entirely devoted to the British exploitation film studio in France. Though the studio had existed since the mid-1940s (after a few productions in the mid-1930s), it gained notoriety in the mid-1950s with a series of readaptations of classic -

Country Update

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS MARCH 1, 2021 | PAGE 1 OF 18 INSIDE BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] What’s Up With Strait Talk With Songwriter Dean Dillon Bryan’s ‘Down’ >page 4 As He Awaits His Hall Of Fame Induction Academy Of Country Life-changing moments are not always obvious at the time minutes,” says Dillon. “I was in shock. My life is racing through Music Awards they occur. my mind, you know? And finally, I said something stupid, like, Raise Diversity So it’s easy to understand how songwriter Dean Dillon (“Ten- ‘Well, I’ve given my life to country music.’ She goes, ‘Well, we >page 10 nessee Whiskey,” “The Chair”) missed the 40th anniversary know you have, and we’re just proud to tell you that you’re going of a turning point in his career in February. He and songwriter to be inducted next fall.’ ” Frank Dycus (“I Don’t Need Your Rockin’ Chair,” “Marina Del The pandemic screwed up those plans. Dillon couldn’t even Rey”) were sitting on the front porch at Dycus’ share his good fortune until August — “I was tired FGL, Lambert, Clark home/office on Music Row when producer Blake of keeping that a secret,” he says — and he’s still Get Musical Help Mevis (Keith Whitley, Vern Gosdin) pulled over waiting, likely until this fall, to enter the hall >page 11 at the curb and asked if they had any material. along with Marty Stuart and Hank Williams Jr. He was about to record a new kid and needed Joining with Bocephus is apropos: Dillon used some songs.