Survey Report Holds Valuable Information Relating to the Development of Marathon, and Monroe County Overall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tavernier House

FILM REVIEW Eat, drink and be merry Winterbottom’s 2005’s This British “Tristram Shandy: A Cock import is wit and Bull Story.” Coogan is probably writ large most recognizable in the KEY WEST U.S. from his role as ‘The Trip’, 107 minutes, Octavius in the two “Night Unrated, opens Friday, Aug. At The Museum” films. 26, Tropic Cinema, Key “The Trip” reunites the trio West in a very funny movie Beer masters compete about, well, basically about Two British guys go on nothing. While the movie a road trip through a pretty only lightly touches on the KEYS but purpose of the trip, the for bragging rights FILM rainy director wisely concentrates country- on the repartee between the economies. side, two main characters. The Brewfest touts “Recently, China has eat at In L’Attitudes end result is an enjoyable overtaken the U.S. as the several film. 140 beers for largest beer economy,” con- restau- “The Trip” started as a Sept. 1-5 event cluded economists Liesbeth rants, TV series in the UK and Colen and Johan Swinnen of talk and Winterbottom has woven L’Attitudes Staff the University of Leuven, talk some of those episodes into writing in the American some a 107-minute film. The Picture 12 dozen differ- trade industry’s magazine. more, do premise is that Coogan is ent beers on tap or chilled in Lest we allow China to impres- hired by a London newspa- bottles waiting to quench usurp our longstanding beer Craig Wanous sions of per to write about fine your thirst. -

Repurposing the East Coast Railway: Florida Keys Extension a Design Study in Sustainable Practices a Terminal Thesis Project by Jacqueline Bayliss

REPURPOSING THE EAST COAST RAILWAY: FLORIDA KEYS EXTENSION A DESIGN STUDY IN SUSTAINABLE PRACTICES A terminal thesis project by Jacqueline Bayliss College of Design Construction and Planning University of Florida Spring 2016 University of Florida Spring 2016 Terminal Thesis Project College of Design Construction & Planning Department of Landscape Architecture A special thanks to Marie Portela Joan Portela Michael Volk Robert Holmes Jen Day Shaw Kay Williams REPURPOSING THE EAST COAST RAILWAY: FLORIDA KEYS EXTENSION A DESIGN STUDY IN SUSTAINABLE PRACTICES A terminal thesis project by Jacqueline Bayliss College of Design Construction and Planning University of Florida Spring 2016 Table of Contents Project Abstract ................................. 6 Introduction ........................................ 7 Problem Statement ............................. 9 History of the East Coast Railway ...... 10 Research Methods .............................. 12 Site Selection ............................... 14 Site Inventory ............................... 16 Site Analysis.................................. 19 Case Study Projects ..................... 26 Limitations ................................... 28 Design Goals and Objectives .................... 29 Design Proposal ............................ 30 Design Conclusions ...................... 40 Appendices ......................................... 43 Works Cited ........................................ 48 Figure 1. The decommissioned East Coast Railroad, shown on the left, runs alongside the Overseas -

National Park Service Climate Change Action Plan 2012-2014 Letter from the Director

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Climate Change Response Program Climate Change Action Plan 2012–2014 Golden Gate National Recreation Area California, is one of many coastal parks experiencing rising sea level. NPS photo courtesy Will Elder. TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR .................................... 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................ 6 CONTEXT FOR ACTION ............................................ 8 National Directives ............................................. 9 A Servicewide Climate Change Response ...................... 9 1 The Role of the NPS in a Changing Climate ..................10 Flexible Planning ..............................................11 IDENTIFYING NEAR-TERM PRIORITIES ......................... 12 Criteria for Prioritization ......................................13 Eight Emphasis Areas for Action ...............................13 2 Table 1: NPS Commitments to High-Priority Actions ..........................................20 PREPARING FOR NEW CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES ........................................... 28 What to Expect in the Next Few Years ........................29 3 The Road Ahead ...............................................32 CONCLUSION ...................................................34 National Park Service Climate Change Action Plan 2012-2014 Letter from the Director lmost one hundred years ago – long before “the greenhouse effect” or “sea level rise” or even A“climate change” were common concepts – a -

Bac Rpt for February 2021.Xlsx

FKAA BACTERIA MONTHLY REPORT PWSID# 4134357 Month: February 2021 H.R.S. LAB # E56717 & E55757 MMO‐MUG/ Cl2 pH RETEST MMO‐MUG/ 100ML DATE 100ML Cl2 pH SERVICE AREA # 1 S.I. LAB Date Sampled: 2/2/2021 125 Las Salinas Condo‐3930 S. Roosevelt Blvd. A 3.2 9.03 126 Key West by the Seas Condo‐2601 S. Roosevelt Blvd. A 3.0 9.01 127 Advanced Discount Auto Parts‐1835 Flagler Ave. A 2.7 9.00 128 1800 Atlantic Condo‐1800 Atlantic Blvd. A 2.9 9.02 129 807 Washington St. (#101) A 2.7 9.00 130 The Reach Resort‐1435 Simonton St. A 3.2 9.01 131 Dewey House‐504 South St. A 3.2 9.01 132 Almond Tree Inn‐512 Truman Ave. A 2.6 9.00 133 Harbor Place Condo‐107 Front St. A 3.7 9.04 134 Court House‐302 Fleming St. A 3.4 9.09 135 Old Town Trolley Barn‐126 Simonton St. A 2.7 9.00 136 Land's End Village‐ #2 William St. A 2.8 9.00 137 U.S. Navy Peary Court Housing‐White/Southard St. A 3.0 9.00 138 Dion's Quick Mart‐1000 White St. A 2.9 9.20 139 Bayview Park‐1400 Truman Ave. A 2.5 9.21 140 Mellow Ventures‐1601 N. Roosevelt Blvd. A 3.1 9.22 141 VFW Post 3911‐2200 N.Roosevelt Blvd. A 3.1 9.25 143 US Navy Sigsbee Park Car Wash‐Felton Rd. A 2.8 9.25 144 Conch Scoops‐3214 N. -

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Dry Tortugas National Park

LONG-RANGE INTERPRETIVE PLAN Dry Tortugas National Park 2003 Cover Photograph: Aerial view of Fort Jefferson on Garden Key (fore- ground) and Bush Key (background). COMPREHENSIVE INTERPRETIVE PLAN Dry Tortugas National Park 2003 LONG-RANGE INTERPRETIVE PLAN Dry Tortugas National Park 2003 Prepared by: Department of Interpretive Planning Harpers Ferry Design Center and the Interpretive Staff of Dry Tortugas National Park and Everglades National Park INTRODUCTION About 70 miles west of Key West, Florida, lies a string of seven islands called the Dry Tortugas. These sand and coral reef islands, or keys, along with 100 square miles of shallow waters and shoals that surround them, make up Dry Tortugas National Park. Here, clear views of water and sky extend to the horizon, broken only by an occasional island. Below and above the horizon line are natural and historical treasures that continue to beckon and amaze those visitors who venture here. Warm, clear, shallow, and well-lit waters around these tropical islands provide ideal conditions for coral reefs. Tiny, primitive animals called polyps live in colonies under these waters and form skeletons from cal- cium carbonate which, over centuries, create coral reefs. These reef ecosystems support a wealth of marine life such as sea anemones, sea fans, lobsters, and many other animal and plant species. Throughout these fragile habitats, colorful fishes swim, feed, court, and thrive. Sea turtles−−once so numerous they inspired Spanish explorer Ponce de León to name these islands “Las Tortugas” in 1513−−still live in these waters. Loggerhead and Green sea turtles crawl onto sand beaches here to lay hundreds of eggs. -

USGS 7.5-Minute Image Map for Crawl Key, Florida

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR CRAWL KEY QUADRANGLE U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY FLORIDA-MONROE CO. 7.5-MINUTE SERIES 81°00' 57'30" 55' 80°52'30" 5 000m 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 24°45' 01 E 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 690 000 FEET 11 12 24°45' Grassy Key 27 000m 37 N 5 27 BANANA BLVD 37 Florida Crawl Key Bay Long Point Key 35 150 000 FEET «¬5 T65S R33E ¤£1 Little Crawl Key Valhalla 5 34 MARATHON 2736 Fat Deer 2736 Fat Deer Key Key Deer Key T66S R33ER M D LU CO P C3O 2735 2735 O C E O R N O ATLANTIC M OCEAN East 2734 Turtle Shoal 2734 2733 2733 Imagery................................................NAIP, January 2010 Roads..............................................©2006-2010 Tele Atlas Names...............................................................GNIS, 2010 42'30" 42'30" Hydrography.................National Hydrography Dataset, 2010 Contours............................National Elevation Dataset, 2010 Hawk Channel 2732 2732 West Turtle Shoal FLORIDA Coffins Patch 2731 2731 2730 2730 2729 2729 CO E ATLANTIC RO ON OCEAN M 40' 40' 2727 2727 2726 2726 2725 2725 110 000 FEET 2724 2724000mN 24°37'30" 24°37'30" 501 660 000 FEET 502 5 5 5 5 507 5 5 5 511 512000mE 81°00' 03 04 57'30" 05 06 08 55' 09 10 80°52'30" ^ Produced by the United States Geological Survey SCALE 1:24 000 ROAD CLASSIFICATION 7 North American Datum of 1983 (NAD83) 3 FLORIDA Expressway Local Connector 3 World Geodetic System of 1984 (WGS84). -

Reconstruction of Fire History in the National Key Deer Refuge, Monroe County, Florida, U.S.A.: the Palmetto Pond Macroscopic Charcoal Record

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2012 Reconstruction of Fire History in the National Key Deer Refuge, Monroe County, Florida, U.S.A.: The Palmetto Pond Macroscopic Charcoal Record Desiree Lynn Kocis [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Physical and Environmental Geography Commons Recommended Citation Kocis, Desiree Lynn, "Reconstruction of Fire History in the National Key Deer Refuge, Monroe County, Florida, U.S.A.: The Palmetto Pond Macroscopic Charcoal Record. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2012. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1175 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Desiree Lynn Kocis entitled "Reconstruction of Fire History in the National Key Deer Refuge, Monroe County, Florida, U.S.A.: The Palmetto Pond Macroscopic Charcoal Record." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Geography. Sally P. Horn, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Liem Tran, Henri Grissino-Mayer Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Reconstruction of Fire History in the National Key Deer Refuge, Monroe County, Florida, U.S.A: The Palmetto Pond Macroscopic Charcoal Record A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Desiree Lynn Kocis May 2012 Copyright © 2012 by Desiree Kocis All rights reserved. -

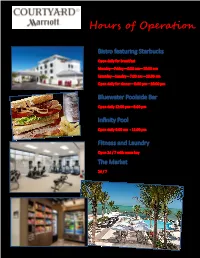

Hours of Operation

Hours of Operation Bistro featuring Starbucks Open daily for breakfast Monday—Friday—6:30 am—10:30 am Saturday—Sunday—7:00 am—10:30 am Open daily for dinner—5:00 pm—10:00 pm Bluewater Poolside Bar Open daily 12:00 pm—8:00 pm Infinity Pool Open daily 6:00 am - 11:00 pm Fitness and Laundry Open 24 / 7 with room key The Market 24 / 7 Airports Marathon Jet Center About 5 minutes away 3.5 Miles Www.marathonjetcenter.com Getting Marathon General Aviation About 6 minutes away Around in the 6 Miles Www.marathonga.com Florida Keys Miami International Airport About 2 hours and 15 minutes away 115 Miles Www.miami-airport.com Fort Lauderdale Airport About 2 hours and 45 minutes away 140 Miles Www.fortlauderdaleinternationalairport.com ******************** Complimentary Shuttle Service Contact the front desk for assistance Taxi and Shuttle Dave’s Island Taxi—305.289.8656 Keys Shuttle—305.289.9997 ******************** Car Rental Enterprise — 305.289.7630 Avis — 305.743.5428 Budget — 305.743.3998 ********************* Marathon Chamber of Commerce 12222 Overseas Highway, Marathon, Florida 33050 305-743-5417 Don’t Miss It in the Florida Keys Key Largo Marathon John Pennekamp State Park Turtle Hospital 102601 Overseas Highway 2396 Overseas Highway 305. 451. 6300 305. 743. 2552 African Queen and Glass Boat Dolphin Research Center U.S. 1 and Mile Marker 100 58901 Overseas Highway 305. 451. 4655 305. 289. 1121 Florida Keys Aquarium Encounters Islamorada 11710 Overseas Highway 305. 407. 3262 Theatre of the Sea 84721 Oversea Highway Sombrero Beach 305.664.2431 Mile Marker 50 305. -

Coast Guard, DHS § 100.701

Coast Guard, DHS § 100.701 TABLE TO § 100.501—ALL COORDINATES LISTED IN THE TABLE TO § 100.501 REFERENCE DATUM NAD 1983—Continued No. Date Event Sponsor Location 68 .. June 25 and 26, Thunder on the Kent Narrows All waters of Prospect Bay enclosed by the following points: 2011. Narrows. Racing Asso- Latitude 38°57′52.0″ N., longitude 076°14′48.0″ W., to lati- ciation. tude 38°58′02.0″ N., longitude 076°15′05.0″ W., to latitude 38°57′38.0″ N., longitude 076°15′29.0″ W., to latitude 38°57′28.0″ N., longitude 076°15′23.0″ W., to latitude 38°57′52.0″ N., longitude 076°14′48.0″ W. [USCG–2007–0147, 73 FR 26009, May 8, 2008, as forbid and control the movement of all amended by USCG–2009–0430, 74 FR 30223, vessels in the regulated area(s). When June 25, 2009; 75 FR 750, Jan. 6, 2010; USCG– hailed or signaled by an official patrol 2011–0368, 76 FR 26605, May 9, 2011] vessel, a vessel in these areas shall im- EFFECTIVE DATE NOTE: By USCG–2010–1094, mediately comply with the directions at 76 FR 13886, Mar. 15, 2011, the Table to given. Failure to do so may result in § 100.501 was amended by suspending lines No. expulsion from the area, citation for 13, No. 19, No. 21 and No. 23, and adding a new failure to comply, or both. heading and entries 65, 66, 67, and 68, effec- tive Apr. 1, 2011 through Sept. 1, 2011. -

National Park Service Mission 66 Era Resources B

NPS Form 10-900-b (Rev. 01/2009) 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form Is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructil'.r!§ ~ ~ tloDpl lj~~r Bulletin How to Complete the Mulliple Property Doc11mentatlon Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the req lBtEa\oJcttti~ll/~ a@i~8CPace, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items X New Submission Amended Submission AUG 1 4 2015 ---- ----- Nat Register of Historie Places A. Name of Multiple Property Listing NatioAal Park Service National Park Service Mission 66 Era Resources B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Pre-Mission 66 era, 1945-1955; Mission 66 program, 1956-1966; Parkscape USA program, 1967-1972, National Park Service, nation-wide C. Form Prepared by name/title Ethan Carr (Historical Landscape Architect); Elaine Jackson-Retondo, Ph.D., (Historian, Architectural); Len Warner (Historian). The Collaborative Inc.'s 2012-2013 team comprised Rodd L. Wheaton (Architectural Historian and Supportive Research), Editor and Contributing Author; John D. Feinberg, Editor and Contributing Author; and Carly M. Piccarello, Editor. organization the Collaborative, inc. date March 2015 street & number ---------------------2080 Pearl Street telephone 303-442-3601 city or town _B_o_ul_d_er___________ __________st_a_te __ C_O _____ zi~p_c_o_d_e_8_0_30_2 __ _ e-mail [email protected] organization National Park Service Intermountain Regional Office date August 2015 street & number 1100 Old Santa Fe Trail telephone 505-988-6847 city or town Santa Fe state NM zip code 87505 e-mail sam [email protected] D. -

Appendix C - Monroe County

2016 Supplemental Summary Statewide Regional Evacuation Study APPENDIX C - MONROE COUNTY This document contains summaries (updated in 2016) of the following chapters of the 2010 Volume 1-11 Technical Data Report: Chapter 1: Regional Demographics Chapter 2: Regional Hazards Analysis Chapter 4: Regional Vulnerability and Population Analysis Funding provided by the Florida Work completed by the Division of Emergency Management South Florida Regional Council STATEWIDE REGIONAL EVACUATION STUDY – SOUTH FLORIDA APPENDIX C – MONROE COUNTY This page intentionally left blank. STATEWIDE REGIONAL EVACUATION STUDY – SOUTH FLORIDA APPENDIX C – MONROE COUNTY TABLE OF CONTENTS APPENDIX C – MONROE COUNTY Page A. Introduction ................................................................................................... 1 B. Small Area Data ............................................................................................. 1 C. Demographic Trends ...................................................................................... 4 D. Census Maps .................................................................................................. 9 E. Hazard Maps .................................................................................................15 F. Critical Facilities Vulnerability Analysis .............................................................23 List of Tables Table 1 Small Area Data ............................................................................................. 1 Table 2 Health Care Facilities Vulnerability -

Sea Level Rise and Inundation Projections for Everglades, Biscayne and Dry Tortugas National Park Infrastructure

Sea Level Rise and Inundation Projections for Everglades, Biscayne and Dry Tortugas National Park Infrastructure November 21, 2016 South Florida Natural Resources Center Everglades National Park Technical Report SFNRC 2016:11-21 Cover picture shows the Flamingo visitor center on Florida Bay. Sea Level Rise and Inundation Projections for Everglades, Biscayne and Dry Tortugas National Park Infrastructure November 21, 2016 Technical Report SFNRC 2016:11-21 South Florida Natural Resources Center Everglades National Park Homestead, Florida National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Sea Level Rise and Inundation Projections i Sea Level Rise and Inundation Projections for Everglades, Biscayne and Dry Tortugas National Park Infrastructure November 21, 2016 Technical Report SFNRC 2016:11-21 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY It is unequivocal that climate is warming, and since the 1950s many of the observed changes are unprecedented over decades to millennia. The atmosphere and ocean have warmed, snow and ice have diminished, sea level has risen, and concentrations of greenhouse gases have increased. One of the most robust indicators of a warming climate is rising sea level driven by thermal expansion of ocean water and addition of land-based ice-melt to the ocean, however, sea level rise is not evenly distributed around the globe and the response of a coastline is highly dependent on local natural and human settings. This is particularly evident at the southern end of the Florida peninsula where low elevations and exceedingly flat topography provide an ideal setting for encroachment of the sea. Here, we illustrate projected impacts of sea level rise to infrastructure in Everglades, Biscayne and Dry Tortugas National Parks at four time horizons: 2025, 2050, 2075 and 2100, and under two sea level rise scenarios, a low projection and a high projection.