Montana's Scoop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parking Who Was J 60P NAMES WARREN Gary Cooper

Metro, is still working on the same tator state that she was going to thing cute.” He takes me into the day,* had to dye her brown hair is his six- contract she signed when she was marry Lew Ayres when she gets her television room, and there yellow. Because, Director George wife. Seems to year-old daughter Jerilyn dining Mickey Rooney’s freedom from Ronald Reagan. She Seaton reasoned, "They wouldn't me she rates something new in alone, while at the same time she Hollywood: that’s because have a brunette daughter.” the way of remuneration. says quite interesting, watches a grueling boxing match on Back in Film is from Business, Draft May Take Nancy Guild, now recovered from she hasn’t yet had a date with Lew. the radio. Charles Grapewin retiring Hughes, making pictures when he finishes her session with Orson Welles in John Garfield is doing a Bing Gregory Peck gets Robyt Siod- Kay Thompson’s into two his present film, "Sand,” after 52 “Cagliostro,” goes pictures for his Franchot Tone. mak to direct him in "Great Sinner.” Minus Brilliance of Crosby pal, years in the business. And they Schary Williams Bros. —the Clifton Webb “Belvedere Goes That's a break for them both. He in a bit role in Fran- used to the movies were a By Jay Carmody to College,” and “Bastille” for Wal- appears Celeste Holm and Dan Dailey are say pre- carious ferocious whose last Hollywood Sheilah Graham ter Wanger. chot's picture, “Jigsaw.” both so their Coleen profession! Howard Hughes, the independent By blond, daughter North American Richard under (Released by sensation was production of the stupid, bad-taste "The Outlaw," has Burt Lancaster, thwarted in his Conte, suspension Nina Foch is the only star to beat Townsend, in "Chicken Every Sun- Newspaper Alliance.) at 20thtFox for refusing to work in come up with another that has the movie capital talking. -

Robertson Davies Fifth Business Fifth Business Definition: Those Roles Which, Being Neither Those of Hero Nor Heroine, Confidant

Robertson Davies Fifth Business Fifth Business Definition: Those roles which, being neither those of Hero nor Heroine, Confidante nor Villain, but which were nonetheless essential to bring about the Recognition or the denouement, were called the Fifth Business in drama and opera companies organized according to the old style; the player who acted these parts was often referred to as Fifth Business. —Tho. Overskou, Den Daaske Skueplads I. Mrs. Dempster 1 My lifelong involvement with Mrs. Dempster began at 8 o’clock p.m. on the 27th of December, 1908, at which time I was ten years and seven months old. I am able to date the occasion with complete certainty because that afternoon I had been sledding with my lifelong friend and enemy Percy Boyd Staunton, and we had quarrelled, because his fine new Christmas sled would not go as fast as my old one. Snow was never heavy in our part of the world, but this Christmas it had been plentiful enough almost to cover the tallest spears of dried grass in the fields; in such snow his sled with its tall runners and foolish steering apparatus was clumsy and apt to stick, whereas my low-slung old affair would almost have slid on grass without snow. The afternoon had been humiliating for him, and when Percy as humiliated he was vindictive. His parents were rich, his clothes were fine, and his mittens were of skin and came from a store in the city, whereas mine were knitted by my mother; it was manifestly wrong, therefore, that his splendid sled should not go faster than mine, and when such injustice showed itself Percy became cranky. -

Woman War Correspondent,” 1846-1945

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository CONDITIONS OF ACCEPTANCE: THE UNITED STATES MILITARY, THE PRESS, AND THE “WOMAN WAR CORRESPONDENT,” 1846-1945 Carolyn M. Edy A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication. Chapel Hill 2012 Approved by: Jean Folkerts W. Fitzhugh Brundage Jacquelyn Dowd Hall Frank E. Fee, Jr. Barbara Friedman ©2012 Carolyn Martindale Edy ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract CAROLYN M. EDY: Conditions of Acceptance: The United States Military, the Press, and the “Woman War Correspondent,” 1846-1945 (Under the direction of Jean Folkerts) This dissertation chronicles the history of American women who worked as war correspondents through the end of World War II, demonstrating the ways the military, the press, and women themselves constructed categories for war reporting that promoted and prevented women’s access to war: the “war correspondent,” who covered war-related news, and the “woman war correspondent,” who covered the woman’s angle of war. As the first study to examine these concepts, from their emergence in the press through their use in military directives, this dissertation relies upon a variety of sources to consider the roles and influences, not only of the women who worked as war correspondents but of the individuals and institutions surrounding their work. Nineteenth and early 20th century newspapers continually featured the woman war correspondent—often as the first or only of her kind, even as they wrote about more than sixty such women by 1914. -

"Hello, Dolly!" at Auditorium Theatre, Jan. 27

AUDITORIUM THEATRE ROCHESTER JANUARY 27 BROAD'lMAY TO FEBRUARY 1 THEATRE LEAGUE 1969 YVONNE DECARLO m HELLO, gOLL~I llng1na1ly D1rected and ChoreogrJphPd by GOWER CHDIPIOII Th1s Pr oductiOn D1rected by LUCIA VICTOR ~tenens FEATURING OUR SATURDAY NITE SPECIAL Prime Rib of Beef Au Jus Baked Potato with Sour Cream & Chives Vegetable - Salad - Coffee $3.95 . ALSO MANY OTHER DELICIOUS ITEMS Stop in for dinner before the show or after the show for a late evening anack SERVING 7 DAYS & NITES FROM 11 A.M. till 2 A.M. 1501 UNIVERSITY AVE . EXTENSION PLENTY OF FlEE PAIICING For Reservations Call: 271-9635 or 271-9494 PARTY AND BANQUET ACCOMMODATIONS Consult Us For Your Banquets And Part i es . • • we w i ll be glad to hove you . Wm. Fisher, Budd Filippo & Ken Gaston proudly present YVONNE DE CARLO in The New York Critics Circle & Tony Award Winn1ng Mus1cal "HELLO, DOLLVI 11 Book IJy Music & Lyrics by MICHAEL STEW ART JERRY HERMAN Based on the originc~l play by Thornton Wilder also starring DON DE LEO with Kathleen Devine George Cavey Rick Grimaldi Suzanne Simon David Gary Althea Rose Edie Pool Norman Fredericks Settings Designed by Lighting Consultant Costumes by Oliver Smith Gerald Richland freddy Wittop Dance & Incidental Music Orchestration by Arrangements by Musical Dirt!cliun by Phillip J. Lang Peter Howard Gil Bowers [)ances Staged for this Production hy Jack Craig Original Choreography & Direction by GOWER CHAMPION This Production Staged by Lucia Victor PHIL'S PANTRYS J A Y ' S "REAL DELICATESSENS" Fresh Sliced Cold Meats D I N E R Home Made Salads & Baked Beans lWO LOCAnONS 2612 W. -

![1942-01-09 [P 10]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8873/1942-01-09-p-10-148873.webp)

1942-01-09 [P 10]

Radio DA IS OFFICERS OUT OUR WAY By J. B. Williams OUR BOARDING HOUSE .. with . Major HooPie Today’s Programs i-*" ^ ' r kuow whut yo’re im stiffVs N/well ,x don't M WE WANT TO TIP YEAH, WHEN ¥THANKS— A- LAUGH IU’ AT / DLL ADMIT Y TIME, COWBOSSI BLAME THE YOu'<^f IET PROMOTIONS TIMERS! JULIET—THERE'S H, HE'S BROKE ¥ ALWAYS BEEN AN V WMFD 1400 KC X LOOK LIKE A HOG I SPENT TWO OLD OFF, ^ Wilmington HERDER MONTHS IM IITHIMKI’D A WILD ANIMAL IN THE M HE SETS EASY TARGET Dance. AM’I’M A-GOIM’ ) </( TOR Mjf FRIDAY, JAN. 9 3:30—Let’s AW SOOWER 3:55—Transradio News. T’STAY THETAWAY, TILL /TH1 BRUSH / j HOUSE/—IF JAKE HITS A BEAR <6?TOUCH/— MUST BE A Majors Martin, Kendall Ad- TWO CAYS LOOK LIKE ^ jjp 7:30—Family Altar, Rev. J. A. Sulli- 4:00—Club Matinee. COWBOYS SPEWD MORE \ / YOU FOR A SILLY STREAKT van. 4:15—Monitor Views the News. TIME IU TH’ BRESH IW TOWU— / A REAL- LOAN,PRETENdXtRAPFOR }| w-fH 5V. Lee. vanced To Rank Of \ 7:45—Red, White and Blue Network. 4:30—Piano Ramblings—H. TRYIN)’ TO BE COWBOVS NIOVJ IE YOU SECTIOM HAWD YOU'RE HARD OF HEAR- MEN, INHERITED FROM News 4:45—Club Matinee—A. P. News. | j J[ 8:00—European Roundup. THAW IN) CABARETS I SIT OUE O' THAW A AND START TALKING ) WOMEN fA 8:10— News from our 5:00—Adventure Stories. Lieutenant-Colonel |NG GRANDPA,WHO jHWq Capital. -

Pictures Afraid You Have Your Dalys Mixed Up

What's New SUSAN HAYWARD from Coast to Coast exciting (Continued from page 10) really sisters. Their ages are: Christine, 25, Dorothy, 23, and Phyllis, 22.... Miss A. Y., Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Johnny Des- mond is on a two -month leave of absence new from the Breakfast Club program, so he can make personal appearances. He is due back on the show October 23.... Miss J. F., San Antonio, Texas: Yes, John Daly is married, and has been for many years. I'm pictures afraid you have your Dalys mixed up. In- JEFF HUNTER cidentally, John recently signed a long- term contract with the American Broad- casting Company as a vice -president in of charge of news. He will continue to be Off-Guard Candids Your the emcee on What's My Line? however. To all of the readers who wrote about Frank Dane, who played Knap Drewer on Favorite Movie Stars the Hawkins Falls show: Frank is no longer on the program because the part of Drewer is no longer in the script. Knap chartered All the selective skill of our ace a private plane to fly from London to the * Isle of Man, in the story, and was killed cameramen went into the making when the plane crashed into the Irish of these startling, 4 x 5, quality DORIS DAY Sea. glossy prints. What ever Happened To . ? John Beal, the movie actor, who used to appear on the Freedom Rings TV show? Since leaving this show, John hasn't been * New poses and names are con- on any regular program, but has been stantly added. -

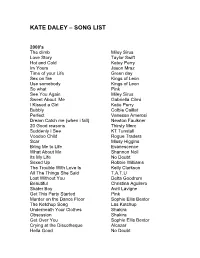

Kate Daley – Song List

KATE DALEY – SONG LIST 2000's The climb Miley Sirus Love Story Taylor Swift Hot and Cold Katey Perry Im Yours Jason Mraz Time of your Life Green day Sex on fire Kings of Leon Use somebody Kings of Leon So what Pink See You Again Miley Sirus Sweet About Me Gabriella Cilmi I Kissed a Girl Katie Perry Bubbly Colbie Caillat Perfect Vanessa Amerosi Dream Catch me (when i fall) Newton Faulkner 20 Good reasons Thirsty Merc Suddenly I See KT Tunstall Voodoo Child Rogue Traders Scar Missy Higgins Bring Me to Life Evanescence What About Me Shannon Noll Its My Life No Doubt Sexed Up Robbie Williams The Trouble With Love Is Kelly Clarkson All The Things She Said T.A.T.U Lost Without You Delta Goodrem Beautiful Christina Aguilero Skater Boy Avril Lavigne Get This Party Started Pink Murder on the Dance Floor Sophie Ellis Bextor The Ketchup Song Las Ketchup Underneath Your Clothes Shakira Obsession Shakira Get Over You Sophie Ellis Bextor Crying at the Discotheque Alcazar Hella Good No Doubt Lets Get Loud Jennifer Lopez Don’t Stop Moving S Club 7 Cant Get you Out of My Head Kylie Minogue I’m Like a Bird Nelly Fertado Absolutely Everybody Vanessa Amorosi Fallin’ Alicia Keys I Need Somebody Bardot Lady marmalade Moulin Rouge Drops of Jupiter Train Out of Reach Gabrielle (Bridgett Jones Dairy) Hit em up in Style Blu Cantrell Breathless The Corrs Buses and trains Bachelor Girl Shine Vanessa Amorosi What took you so long Emma B Overload Sugarbabes Cant Fight the Moonlight Leeann Rhymes (Coyote Ugly) Sunshine on a Rainy Day Christine Anu On a Night Like This -

Papéis Normativos E Práticas Sociais

Agnes Ayres (1898-194): Rodolfo Valentino e Agnes Ayres em “The Sheik” (1921) The Donovan Affair (1929) The Affairs of Anatol (1921) The Rubaiyat of a Scotch Highball Broken Hearted (1929) Cappy Ricks (1921) (1918) Bye, Bye, Buddy (1929) Too Much Speed (1921) Their Godson (1918) Into the Night (1928) The Love Special (1921) Sweets of the Sour (1918) The Lady of Victories (1928) Forbidden Fruit (1921) Coals for the Fire (1918) Eve's Love Letters (1927) The Furnace (1920) Their Anniversary Feast (1918) The Son of the Sheik (1926) Held by the Enemy (1920) A Four Cornered Triangle (1918) Morals for Men (1925) Go and Get It (1920) Seeking an Oversoul (1918) The Awful Truth (1925) The Inner Voice (1920) A Little Ouija Work (1918) Her Market Value (1925) A Modern Salome (1920) The Purple Dress (1918) Tomorrow's Love (1925) The Ghost of a Chance (1919) His Wife's Hero (1917) Worldly Goods (1924) Sacred Silence (1919) His Wife Got All the Credit (1917) The Story Without a Name (1924) The Gamblers (1919) He Had to Camouflage (1917) Detained (1924) In Honor's Web (1919) Paging Page Two (1917) The Guilty One (1924) The Buried Treasure (1919) A Family Flivver (1917) Bluff (1924) The Guardian of the Accolade (1919) The Renaissance at Charleroi (1917) When a Girl Loves (1924) A Stitch in Time (1919) The Bottom of the Well (1917) Don't Call It Love (1923) Shocks of Doom (1919) The Furnished Room (1917) The Ten Commandments (1923) The Girl Problem (1919) The Defeat of the City (1917) The Marriage Maker (1923) Transients in Arcadia (1918) Richard the Brazen (1917) Racing Hearts (1923) A Bird of Bagdad (1918) The Dazzling Miss Davison (1917) The Heart Raider (1923) Springtime à la Carte (1918) The Mirror (1917) A Daughter of Luxury (1922) Mammon and the Archer (1918) Hedda Gabler (1917) Clarence (1922) One Thousand Dollars (1918) The Debt (1917) Borderland (1922) The Girl and the Graft (1918) Mrs. -

MUSIC LIST Email: Info@Partytimetow Nsville.Com.Au

Party Time Page: 1 of 73 Issue: 1 Date: Dec 2019 JUKEBOX Phone: 07 4728 5500 COMPLETE MUSIC LIST Email: info@partytimetow nsville.com.au 1 THING by Amerie {Karaoke} 100 PERCENT PURE LOVE by Crystal Waters 1000 STARS by Natalie Bassingthwaighte {Karaoke} 11 MINUTES by Yungblud - Halsey 1979 by Good Charlotte {Karaoke} 1999 by Prince {Karaoke} 19TH NERVIOUS BREAKDOWN by The Rolling Stones 2 4 6 8 MOTORWAY by The Tom Robinson Band 2 TIMES by Ann Lee 20 GOOD REASONS by Thirsty Merc {Karaoke} 21 - GUNS by Greenday {Karaoke} 21 QUESTIONS by 50 Cent 22 by Lilly Allen {Karaoke} 24K MAGIC by Bruno Mars 3 by Britney Spears {Karaoke} 3 WORDS by Cheryl Cole {Karaoke} 3AM by Matchbox 20 {Karaoke} 4 EVER by The Veronicas {Karaoke} 4 IN THE MORNING by Gwen Stefani {Karaoke} 4 MINUTES by Madonna And Justin 40 MILES OF ROAD by Duane Eddy 409 by The Beach Boys 48 CRASH by Suzi Quatro 5 6 7 8 by Steps {Karaoke} 500 MILES by The Proclaimers {Karaoke} 60 MILES AN HOURS by New Order 65 ROSES by Wolverines 7 DAYS by Craig David {Karaoke} 7 MINUTES by Dean Lewis {Karaoke} 7 RINGS by Ariana Grande {Karaoke} 7 THINGS by Miley Cyrus {Karaoke} 7 YEARS by Lukas Graham {Karaoke} 8 MILE by Eminem 867-5309 JENNY by Tommy Tutone {Karaoke} 99 LUFTBALLOONS by Nena 9PM ( TILL I COME ) by A T B A B C by Jackson 5 A B C BOOGIE by Bill Haley And The Comets A BEAT FOR YOU by Pseudo Echo A BETTER WOMAN by Beccy Cole A BIG HUNK O'LOVE by Elvis A BUSHMAN CAN'T SURVIVE by Tania Kernaghan A DAY IN THE LIFE by The Beatles A FOOL SUCH AS I by Elvis A GOOD MAN by Emerson Drive A HANDFUL -

Vnesheconombank Group Sustainability Report

Vnesheconombank Group Sustainability Report Vnesheconombank Group Sustainability Report 2013 VNESHECONOMBANK / Vnesheconombank Group Sustainability Report 2013 Contents About the Report ..............................................................................................................................................................................................4 Chairman’s Statement .................................................................................................................................................................................6 Vnesheconombank Group: Key Highlights ........................................................................................................................ 10 Highlights 2013 ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 12 Vnesheconombank’s History ............................................................................................................................................................ 14 1. Vnesh econom bank’s Strategy ................................................................................................................................................. 16 1.1. Priority Business Lines ................................................................................................................................................................ 18 1.2. Strategy Implementation. Sustainability Objectives -

Modern First Ladies: Their Documentary Legacy. INSTITUTION National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 412 562 CS 216 046 AUTHOR Smith, Nancy Kegan, Comp.; Ryan, Mary C., Comp. TITLE Modern First Ladies: Their Documentary Legacy. INSTITUTION National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC. ISBN ISBN-0-911333-73-8 PUB DATE 1989-00-00 NOTE 189p.; Foreword by Don W. Wilson (Archivist of the United States). Introduction and Afterword by Lewis L. Gould. Published for the National Archives Trust Fund Board. PUB TYPE Collected Works General (020) -- Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Archives; *Authors; *Females; Modern History; Presidents of the United States; Primary Sources; Resource Materials; Social History; *United States History IDENTIFIERS *First Ladies (United States); *Personal Writing; Public Records; Social Power; Twentieth Century; Womens History ABSTRACT This collection of essays about the Presidential wives of the 20th century through Nancy Reagan. An exploration of the records of first ladies will elicit diverse insights about the historical impact of these women in their times. Interpretive theories that explain modern first ladies are still tentative and exploratory. The contention in the essays, however, is that whatever direction historical writing on presidential wives may follow, there is little question that the future role of first ladies is more likely to expand than to recede to the days of relatively silent and passive helpmates. Following a foreword and an introduction, essays in the collection and their authors are, as follows: "Meeting a New Century: The Papers of Four Twentieth-Century First Ladies" (Mary M. Wolf skill); "Not One to Stay at Home: The Papers of Lou Henry Hoover" (Dale C. -

Boxoffice Barometer (March 6, 1961)

MARCH 6, 1961 IN TWO SECTIONS SECTION TWO Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents William Wyler’s production of “BEN-HUR” starring CHARLTON HESTON • JACK HAWKINS • Haya Harareet • Stephen Boyd • Hugh Griffith • Martha Scott • with Cathy O’Donnell • Sam Jaffe • Screen Play by Karl Tunberg • Music by Miklos Rozsa • Produced by Sam Zimbalist. M-G-M . EVEN GREATER IN Continuing its success story with current and coming attractions like these! ...and this is only the beginning! "GO NAKED IN THE WORLD” c ( 'KSX'i "THE Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents GINA LOLLOBRIGIDA • ANTHONY FRANCIOSA • ERNEST BORGNINE in An Areola Production “GO SPINSTER” • • — Metrocolor) NAKED IN THE WORLD” with Luana Patten Will Kuluva Philip Ober ( CinemaScope John Kellogg • Nancy R. Pollock • Tracey Roberts • Screen Play by Ranald Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer pre- MacDougall • Based on the Book by Tom T. Chamales • Directed by sents SHIRLEY MacLAINE Ranald MacDougall • Produced by Aaron Rosenberg. LAURENCE HARVEY JACK HAWKINS in A Julian Blaustein Production “SPINSTER" with Nobu McCarthy • Screen Play by Ben Maddow • Based on the Novel by Sylvia Ashton- Warner • Directed by Charles Walters. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents David O. Selznick's Production of Margaret Mitchell’s Story of the Old South "GONE WITH THE WIND” starring CLARK GABLE • VIVIEN LEIGH • LESLIE HOWARD • OLIVIA deHAVILLAND • A Selznick International Picture • Screen Play by Sidney Howard • Music by Max Steiner Directed by Victor Fleming Technicolor ’) "GORGO ( Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents “GORGO” star- ring Bill Travers • William Sylvester • Vincent "THE SECRET PARTNER” Winter • Bruce Seton • Joseph O'Conor • Martin Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents STEWART GRANGER Benson • Barry Keegan • Dervis Ward • Christopher HAYA HARAREET in “THE SECRET PARTNER” with Rhodes • Screen Play by John Loring and Daniel Bernard Lee • Screen Play by David Pursall and Jack Seddon Hyatt • Directed by Eugene Lourie • Executive Directed by Basil Dearden • Produced by Michael Relph.