Olmsted's Police

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 New York No Numbers

NEW YORK, NEW YORK A list celebrating the city that – until last month – never sleeps. These 50 selections reflect the city’s important contributions to history, art, music, literature, cuisine, engineering, transportation, architecture, and leisure. This is an enhanced PDF catalog. If you click on an image or the highlighted headline of any entry, you will be linked to our website where you will find images. We are happy to provide more images or information upon request. In chronological order 1. HARDIE, James. The Description of the City of New York. New York: Samuel Marks, 1827. 8vo. 360 pages. Hand-colored engraved folding map. Contemporary sheep, gilt decorated on spine. Provenance: contemporary ownership inscription on front free endpaper. Binding worn, occasional pale spotting. Large folding map has a small tear at the attachment else very clean and bright. $325 FIRST EDITION. Church 1336; Howes H-184. Sabin 30319. RIVERRUN BOOKS & MANUSCRIPTS NEW YORK HYDRATED 2. RENWICK, James. Report on the Water Power at Kingsbridge near the City of New-York, Belonging to New- York Hydraulic Manufacturing and Bridge Company. New-York: Samuel Marks, 1827. 8vo. 12 pages. Three folding lithographed maps, printed by Imbert. Sewn in original printed wrappers, untrimmed; blue cloth portfolio. Provenance: contemporary signature on front wrapper of D. P. Campbell at 51 Broadway. Wear to wrappers, some light foxing, maps clean and bright. $1,200 FIRST EDITION of this scarce pamphlet on the development of the New York water supply. Renwick was Professor of Natural and Experimental Philosophy and Chemistry at Columbia College, and writes at the request of the directors of the New York Hydraulic Manufacturing and Bridge Company who asked him to examine their property at Kingsbridge. -

Parks, People, and Property Values: the Changing Role of Green Spaces in Antebellum Manhattan

Portland State University PDXScholar History Faculty Publications and Presentations History 4-2017 Parks, People, and Property Values: The Changing Role of Green Spaces in Antebellum Manhattan Catherine McNeur Portland State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/hist_fac Part of the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details McNeur, Catherine, "Parks, People, and Property Values: The Changing Role of Green Spaces in Antebellum Manhattan" (2017). History Faculty Publications and Presentations. 34. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/hist_fac/34 This Post-Print is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Catherine McNeur Parks, People, and Property Values The Changing Role of Green Spaces in Antebellum Manhattan Abstract: The role that parks played in Manhattan changed dramatically during the antebellum period. Originally dismissed as unnecessary on an island embraced by rivers, parks became a tool for real estate development and gentrification in the 1830s. By the 1850s, politicians, journalists, and landscape architects believed Central Park could be a social salve for a city with rising crime rates, increasingly visible poverty, and deepening class divisions. While many factors (public health, the psychological need for parks, and property values) would remain the same, the changing social conversation showed how ideas of public space were transforming, in rhetoric if not reality. When Andrew Jackson Downing penned his famous essays between 1848 and 1851 calling for New York City to build a great public park to rival those in Europe, there was growing support among New Yorkers for a truly public green space. -

Female Sportswriters of the Roaring Twenties

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Communications THEY ARE WOMEN, HEAR THEM ROAR: FEMALE SPORTSWRITERS OF THE ROARING TWENTIES A Thesis in Mass Communications by David Kaszuba © 2003 David Kaszuba Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2003 The thesis of David Kaszuba was reviewed and approved* by the following: Ford Risley Associate Professor of Communications Thesis Adviser Chair of Committee Patrick R. Parsons Associate Professor of Communications Russell Frank Assistant Professor of Communications Adam W. Rome Associate Professor of History John S. Nichols Professor of Communications Associate Dean for Graduate Studies in Mass Communications *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ABSTRACT Contrary to the impression conveyed by many scholars and members of the popular press, women’s participation in the field of sports journalism is not a new or relatively recent phenomenon. Rather, the widespread emergence of female sports reporters can be traced to the 1920s, when gender-based notions about employment and physicality changed substantially. Those changes, together with a growing leisure class that demanded expanded newspaper coverage of athletic heroes, allowed as many as thirty-five female journalists to make inroads as sports reporters at major metropolitan newspapers during the 1920s. Among these reporters were the New York Herald Tribune’s Margaret Goss, one of several newspaperwomen whose writing focused on female athletes; the Minneapolis Tribune’s Lorena Hickok, whose coverage of a male sports team distinguished her from virtually all of her female sports writing peers; and the New York Telegram’s Jane Dixon, whose reports on boxing and other sports from a so-called “woman’s angle” were representative of the way most women cracked the male-dominated field of sports journalism. -

The New-York Historical Society Library Department of Prints, Photographs, and Architectural Collections

Guide to the Geographic File ca 1800-present (Bulk 1850-1950) PR20 The New-York Historical Society 170 Central Park West New York, NY 10024 Descriptive Summary Title: Geographic File Dates: ca 1800-present (bulk 1850-1950) Abstract: The Geographic File includes prints, photographs, and newspaper clippings of street views and buildings in the five boroughs (Series III and IV), arranged by location or by type of structure. Series I and II contain foreign views and United States views outside of New York City. Quantity: 135 linear feet (160 boxes; 124 drawers of flat files) Call Phrase: PR 20 Note: This is a PDF version of a legacy finding aid that has not been updated recently and is provided “as is.” It is key-word searchable and can be used to identify and request materials through our online request system (AEON). PR 000 2 The New-York Historical Society Library Department of Prints, Photographs, and Architectural Collections PR 020 GEOGRAPHIC FILE Series I. Foreign Views Series II. American Views Series III. New York City Views (Manhattan) Series IV. New York City Views (Other Boroughs) Processed by Committee Current as of May 25, 2006 PR 020 3 Provenance Material is a combination of gifts and purchases. Individual dates or information can be found on the verso of most items. Access The collection is open to qualified researchers. Portions of the collection that have been photocopied or microfilmed will be brought to the researcher in that format; microfilm can be made available through Interlibrary Loan. Photocopying Photocopying will be undertaken by staff only, and is limited to twenty exposures of stable, unbound material per day. -

The Times Square Zipper and Newspaper Signs in an Age Of

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive All Faculty Publications 2018-02-01 News in Lights: The imesT Square Zipper and Newspaper Signs in an Age of Technological Enthusiasm Dale L. Cressman PhD Brigham Young University - Provo, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Original Publication Citation Dale L. Cressman, "News in Lights: The imeT s Square Zipper and Newspaper Signs in an Age of Technological Enthusiasm," Journalism History 43:4 (Winter 2018), 198-208 BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Cressman, Dale L. PhD, "News in Lights: The imeT s Square Zipper and Newspaper Signs in an Age of Technological Enthusiasm" (2018). All Faculty Publications. 2074. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/2074 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. DALE L. CRESSMAN News in Lights The Times Square Zipper and Newspaper Signs in an Age of Technological Enthusiasm During the latter half of the nineteenth century, when the telegraph had produced an appetite for breaking news, New York City newspaper publishers used signs on their buildings to report headlines and promote their newspapers. Originally, chalkboards were used to post headlines. But, fierce competition led to the use of new technologies, such as magic lantern projections. These and, later, electrically lighted signs, would evoke amazement. In 1928, during an age of invention, the New York Times installed an electric “moving letter” sign on its building in Times Square. -

Existence Is Justifled by Post-Revolutionary

8 44-* THE N1EW- YORK HERALD, 3MONDAY, FEBRUARY 20, 1922. f J. MEW YORK HERALD ternal index number stood at 3,467, He is supreme master of this veterans. This State alone sends at The Government on war Way. :ert for PUBLISHED BY THB SUN-HERALD the highest record, while the of the Government and theredepartmentIs least eight. The with Spain is Opera Stars in Cone Caruso Fund Daily Calendar CORPORATION. 280 BROADWAY; value of the mark below halfexternalno one in authority to question the represented by Senator Wadswoktii, Unbusinesslike Methods Used In the WORTH 10,000. THE TELEPHONE, a cent was equal to an index number truthfulness of his statements. who served with Battery A of the Choice of a Postmaster. Elaborate Program Given at the Metropolitan in Aid WEATHER. Directors and A. of 4,600. Thus three marks The reason for the of Pennsylvania Field Artillery, In the To Thi New officers: l-'rank Munsey, paper suppression York Herald: It has of Foundation. For Eastern President; Ervln Wardman, Vice-President;! have the same the it Is iB found Porto Rico been my privilege for several to Memorial New York.Clearing to-" Wn\. T. Dowart, Treasurer; R. H. purchasing power Cheka, asserted, campaign; by years Jay, colder ; fair be a visitor by to-night to-morrow Secretary. TltherIngton,within Germany as four paper marks in Moscow's desire to clean house Abdolpu L. Kline ofRepresentative winter in Miami and a and colder; fierce south to west wln<a. By W. J. HKNOGRitON. SI me. Gulli-Curcl. Sir. sang "O happening here has attracted myrecent Gigll For New T>» MAIL SUBSCRIPTION RATES. -

The Great Polar Controversy: D R Cook, Mt. Mckinley, And

THE GREAT POLAR CONTROVERSY: DR COOK, MT. MCKINLEY, AND THE QUEST FOR THE POLES Michael Sfraga College of Rural Alaska P.O. Box 756500 University of Alaska Fairbanks Fairbanks, Alaska 99775 Dennis Stephens Rasmuson Library P. 0. Box 756800 University of Alaska Fairbanks Fairbanks, Alaska 99775 ABSTRACT: In September 1906, Dr. Frederick A. Cook announced to a receptive public that he and Ed Barrill had successfully climbed Mt. McKinley by a "new route from the North." It was a time of keen interest in exploration, particularly of the Arctic and Antarctic regions. While Cook's was initially hailed as the first ascent of North America's highest mountain, his report came under increasing scrutiny as details came to light (or failed to come to light, as the case may be.) The controversy surrounding Cook's Mt. McKinley climb assumed increasing importance in the context of his claim to have been the first to reach the North Pole in April, 1908. The Doctor's claim was disputed by Robert E. Peary, who announced that he himself was first to the Pole in April, 1909, and that Cook "should not be taken too seriously." The chain of events that followed affected the course of exploration at both poles. This paper will examine the bases for Cook's claim to have been first on McKinley and first at the North Pole; the sequence of events that has led to general scepticism about Cook's claims; and the figures in Arctic and Antarctic exploration who were caught up in a dispute that continues to the current day. -

Central Park As a Model for Social Control: Urban Parks, Social Class and Leisure Behavior in Nineteenth-Century America

Journal of Leisure Research Copyright 1999 1999, Vol. 31, No. 4, pp. 420-477 National Recreation and Park Association Central Park as a Model for Social Control: Urban Parks, Social Class and Leisure Behavior in Nineteenth-Century America Dorceta E. Taylor University of Michigan School of Natural Resources and Environment Throughout the nineteenth century, the leading landscape architects and park advocates believed that parks were important instruments of enlightenment and social control. Consequendy, they praised and promoted parks for their health- giving characteristics and character-molding capabilities. Landscape architects used these arguments to convince city governments to invest in elaborate urban parks. Many of these parks became spaces of social and political contestation. As die middle and working class mingled in these spaces, conflicts arose over appropriate park use and behavior. The escalating tensions between the middle and working class led to working class activism for increased access to park space and for greater latitude in defining working class leisure behavior. These struggles laid die foundation for the recreation movement. They were also piv- otal in the emergence of urban, multiple-use parks designed for both active and passive recreation. KEYWORDS: Urban parks, social control, inequality, leisure, recreation, social class, landscape architects, Olmsted, Central Park, environment. Introduction A Social Constructionist Perspective Historical accounts of American parks tend to ignore the constructionist perspective in analyses of urban parks. In addition, few historical analyses view urban parks as contested spaces, do systematic examination of class relations in the parks, or recognize the use of parks as tools of social control. This paper addresses this oversight. -

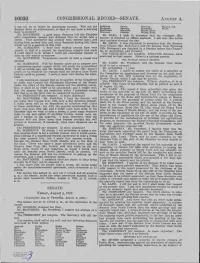

Congressional Record-Sen Ate. August 4

110932 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SEN ATE. AUGUST 4, I can not do so unless by unanimous consent. Will not the Robinson Smoot Sterling Watson, Ind. Sheppard Spencer Trammell Willis Senator move an adjournment, so that we can have a morning Shortridge Stanfield Walsh, Mass. hour to-morrow? J Simmons Stanley Walsh, Mont. M.r. McCUMBER. A good many Senators left the Chamber Mr. DIAL. I wish to announce that my colleague [Mr. after unanimous consent was obtained that. we would take a SMITH] is detained on official business. I ask that this notice recess. That agreement has already been entered into; and may continue through the day. having been entered into, and many Senators having left, there Mr. LADD. I was requested to announce that the Senator would not be a quorum at this time. from Illinois [Mr. McKINLEY] and the Senator from Wyoming 1\ir. HARRISON. I have been staying around here very [Mr. KENDRICK] are detained in a hearing before the Commit closely, so that if a request for unanimous c?nsent was made tee on Agriculture and Forestry. I could object to it~ unless I could get unarumous consent to The PRESIDENT pro tempore. Fifty-ei;ht Senators have take up this matter to-morrow. answered to their names. There is a quorum present. Mr. l\IcCUMBER. Unanimous consent to t.a.ke a recess was granted. THE MUSCLE SHOALS PROJECT. Mr. HARRISON. Will the Senator allow me to propose now l\Ir. LADD. Mr. President, will the Senator from Idaho a unanimous-consent request which will settle the proposition? yield to me a moment? I did so awhile ago., and the Senator from Utah [Mr. -

Villas on the Hudson: an Architectural and Biographical Examination

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Lehman College 1993 Villas on the Hudson: An Architectural and Biographical Examination Janet Butler Munch Lehman College, CUNY How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/le_pubs/229 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] AM E RICAN P U BLISHER S ' CIR CU LAR ======~~~~~====~==== nono L 1860. IN PRESS BY BOSTON TRADE SALE WI LL Cmnl[XCC WEDNESDAY MORNING, D. APPLETON &: COMPANY, ACGCST 1, 1800. r. I' r U l ~. m . W rn A T ,' .. n.ead k Co. ~:~ r-);. 'r ~':7:·: . ~~ ro ~ :~~,L ~~ ~ ~' ~" '\· ~ I . , •. \\" •• & (' 0 C ~ I 5 "" " 0. D.," rr "- Co. TI:I,.N "'1.I.,lr .. lr~ J,. I," \\' ,,~ ~ J ... "., ~L u""~, .... ":0. Coillo. '" IIr o: ~", 1,IIII ·, oI. II L•. ,r . TnE EBOXY IDO L. A :NOl' ti, wriUen by .. Lady of Sew r esiDed. C I• • k. -, "011". ~ Ior n •• d '" ""0 (; 1\ 1 ' ''I 'r ~1I C~ • • lr. :! ,' , . , f lO 4: <.: " II "" .. 1I "r 1:1' " 4: ~ 1 '''U '' '' O '''''C J H l ' l'i" h,oll oi Co LIFE OF 'IHLLI.U! T. PORTER, Ili te EJ itor of .. POtl er', Spirit of the ,., W OuJ" 11 1• .,, 10 . "1 ,\.1 .... Ap Jll r ~ . , .. .. ('D. J\ ~ "' . u. 4: Ti... eo . ~ J C.. G oI. l'. Mr , n . m. or II I' .. ,~, ,, n .. lI.alb" • •• J uhn t::Kch rJ' lry ( bll,i ... -

Department of Parks

Shdting oil the Lakc, Central I'ai-k DEPARTMENT OF PARKS ANNUAL REPORT M. B. GI<OIVN PRIXTING h BINDING CO., 49-57 PARKPIACE, NET\- SORK. DEPARTMENT OF PARKS City of New York PARK BOARD, 1910 CHARLES B. STOVER, President Commissioner for the Boroughs of Manhattan and Richmond THOMAS J. HIGGINS Coinmissioner for the Borough of the Bronx MICHAEL J. KENNEDY Comrnissioncr for the Boroughs of Brooklyn and Queen\ CLINTON H. SMITH, Secretary SAMUEL PARSONS, Landscape Architect PARK BOARD The personnel of the Park Board underwent a change at the beginning of the year, two new Commissioners being appointed by the newly eleded Mayor, the Hon. William J. Gaynor. The new appointments were Charles B. Stover, for the Boroughs of Manhattan and Richmond, and Thomas J. Higgins, for the Borough of The Bronx. Michael J Kennedy, Commissioner for Brooklyn and Queens, was reappointed. In appointing the new members of the Board his Honor expressed the desire that the public be given the fullest measure of enjoyment in the parks, and that they should be maintained with that idea in mind; and also that all considerations of politics, race or creed be eliminated from the government and regulation of the work- ing force. The Board has endeavored to administer the parks from these stand- points during the year. The expenditures for the account of the Board during the year amounted to $27,900, all for salaries of the Commissioners, Secretary and other officers. Report of the Department of Parks Boroughs of Manhattan and Richmond FOR THE YEAR 1910 CHARLESB. STOVER,Con~missioner. -

INFLUENCE of the PARIS HERALD on the LOST GENERATION of WRITERS. the University of Oklahoma, Ph.D

I This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 66—14,260 WOOD Jr., Thomas Wesley, 1920- INFLUENCE OF THE PARIS HERALD ON THE LOST GENERATION OF WRITERS. The University of Oklahoma, Ph.D., 1966 History, modern University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan 0 THOMAS WESLEY WOOD JR. 1967 All Rights Reserved THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE INFLUENCE OF THE PARIS HERALD ON THE LOST GENERATION OF WRITERS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY THOMAS W^' WOOD JR. Norman, Oklahoma 1966 INFLUENCE OF THE PARIS HERALD ON THE LOST GENERATION OF WRITERS APPROVED BY d . DISSERTATION COMMITTEE TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE ..................................................... iv Chapter I. A TRIPLE LEGEND FUSES (Paris, the Herald,.and the Lost Generation) ................................. 1 II. THE HERALD ' S FACTUAL IMAGE ................ 46 III. THE MAJOR LITERARY WORKS O F .HERALD STAFF MEMBERS.......................................... 91 IV. JOURNALISTIC TRAINING AND INFLUENCE OF THE HERALD ON ITS STAFF............................ 122 V. NEWSMAN-LITERATI ASSOCIATIONS....................153 VI. CONCLUSIONS; THE ADJUSTED VIEW. .'.......... 208 BIBLIOGRAPHY................................................238 APPENDICES.............................. 252 111 PREFACE Legend attaching to the Paris Herald presents that publication as a light hearted newspaper which offers a sti mulating haven to destitute and dissolute American writers in France. Like most legends, this one contains some truth. The Herald 's alluring image first attracted me in 19^9 , upon reading Frank Luther Mott’s monumental work on the history of American journalism.^ Exposure to other books in creased my curiosity and I resolved to measure, if possible, the truth of the image for the period 191?-to 1939» The press of circumstances, however, thwarted the project until the summer of 1964.