Yom Hashoah Rabbi Michael Berenbaum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theresienstadt Concentration Camp from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Coordinates: 50°30′48″N 14°10′1″E

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Theresienstadt concentration camp From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Coordinates: 50°30′48″N 14°10′1″E "Theresienstadt" redirects here. For the town, see Terezín. Navigation Theresienstadt concentration camp, also referred to as Theresienstadt Ghetto,[1][2] Main page [3] was established by the SS during World War II in the fortress and garrison city of Contents Terezín (German name Theresienstadt), located in what is now the Czech Republic. Featured content During World War II it served as a Nazi concentration camp staffed by German Nazi Current events guards. Random article Tens of thousands of people died there, some killed outright and others dying from Donate to Wikipedia malnutrition and disease. More than 150,000 other persons (including tens of thousands of children) were held there for months or years, before being sent by rail Interaction transports to their deaths at Treblinka and Auschwitz extermination camps in occupied [4] Help Poland, as well as to smaller camps elsewhere. About Wikipedia Contents Community portal Recent changes 1 History The Small Fortress (2005) Contact Wikipedia 2 Main fortress 3 Command and control authority 4 Internal organization Toolbox 5 Industrial labor What links here 6 Western European Jews arrive at camp Related changes 7 Improvements made by inmates Upload file 8 Unequal treatment of prisoners Special pages 9 Final months at the camp in 1945 Permanent link 10 Postwar Location of the concentration camp in 11 Cultural activities and -

A Resource Guide to Literature, Poetry, Art, Music & Videos by Holocaust

Bearing Witness BEARING WITNESS A Resource Guide to Literature, Poetry, Art, Music, and Videos by Holocaust Victims and Survivors PHILIP ROSEN and NINA APFELBAUM Greenwood Press Westport, Connecticut ● London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rosen, Philip. Bearing witness : a resource guide to literature, poetry, art, music, and videos by Holocaust victims and survivors / Philip Rosen and Nina Apfelbaum. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index. ISBN 0–313–31076–9 (alk. paper) 1. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945)—Personal narratives—Bio-bibliography. 2. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945), in literature—Bio-bibliography. 3. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945), in art—Catalogs. 4. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945)—Songs and music—Bibliography—Catalogs. 5. Holocaust,Jewish (1939–1945)—Video catalogs. I. Apfelbaum, Nina. II. Title. Z6374.H6 R67 2002 [D804.3] 016.94053’18—dc21 00–069153 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright ᭧ 2002 by Philip Rosen and Nina Apfelbaum All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 00–069153 ISBN: 0–313–31076–9 First published in 2002 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America TM The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 Contents Preface vii Historical Background of the Holocaust xi 1 Memoirs, Diaries, and Fiction of the Holocaust 1 2 Poetry of the Holocaust 105 3 Art of the Holocaust 121 4 Music of the Holocaust 165 5 Videos of the Holocaust Experience 183 Index 197 Preface The writers, artists, and musicians whose works are profiled in this re- source guide were selected on the basis of a number of criteria. -

Germans As Victims Remembering the Past in Contemporary Germany 1St Edition Ebook

GERMANS AS VICTIMS REMEMBERING THE PAST IN CONTEMPORARY GERMANY 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Bill Niven | 9781403990433 | | | | | Germans as Victims Remembering the Past in Contemporary Germany 1st edition PDF Book Canadian soldiers display a Nazi flag removed from a building in Xanten, Germany as the Second World War was coming to an end in Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Retrieved 10 December Germans at Fort Bliss and all over the world remembered fallen soldiers and victims of war, tyranny, oppression and terrorism during the German National Day of Mourning, or Volkstrauertag. In , German news magazine Der Spiegel reported that German historian Miriam Gebhardt "believes that members of the US military raped as many as , German women by the time West Germany regained sovereignty in , with most of the assaults taking place in the months immediately following the US invasion of Nazi Germany. How had the shadow of Hitler been overcome? To remember those who were lost, here are some quotes about the Holocaust, from victims, survivors and observers of the horrors. Books by Bill Niven. He spent several years in concentration camps during the Holocaust. She basically said, 'I'm not here to give tips to the Japanese and others. Canada - Alberta , Manitoba , and Nova Scotia. Longden mentions that some rapes were carried out by soldiers either suffering from post traumatic stress or drunk, but that these were not considered as serious as the less common premeditated crimes. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, In Berlin, there are countless physical reminders such as words engraved in cobblestones that mark the arrests of Jews or where families lived before they were pushed out by the Third Reich. -

Yom Hazikaron

Yom Hazikaron : Degrees of Separation www.makomisrael.o rg 0 1 www.makomisrael.org Yom HaZikaron (Israel Remembrance Day): Degrees of Separation This lesson focuses on the challenge of marking Yom HaZikaron (Israel Remembrance Day) for North American Jewry. We explore the notion of commemorating in the wider American context, and expand on this to discuss Israel’s Remembrance Day, and what it means to commemorate from a distance. Goals : • The students will grasp the challenge of commemorating the fallen from a geographical and psychological distance. • The students will be challenged to assess the role of a mourner from afar • The students will explore the meaning of being connected to Jews they have never met • The students will explore various ways of moving beyond the obstacle of distance, allowing North American Jewry to connect to Remembrance Day • The students will be challenged to draw closer and connect to the fallen soldiers in Israel, despite the distance • The students will be given the opportunity to design their own program to mark Israel Remembrance Day Outline : Part 1 : Trigger exercise In the first part, students will participate in drama exercise to introduce the theme of the lesson. Part 2 : Discussion A. September 11 th The students will explore the idea of commemorating from afar by learning about the September 11 th memorial in California, and discussing how they think the tragedy should be marked by those who were not affected personally by it. B. Yom HaZikaron (Israel Remembrance Day) The students will apply their 9/11 discussion to marking Israel’s Remembrance Day and be challenged to think about how they should commemorate the day. -

Humanity in Doubt

HUMANITY IN DOUBT REFLECTIONS AND ESSAYS Philip Weiss HUMANITY IN DOUBT HUMANITY IN DOUBT: REFLECTIONS AND ESSAYS Collection copyright © 2007 by Philip Weiss All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information and retrieval system know known or to be invented, without the permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in review. National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Weiss, Philip Humanity in DoubtlPhilip Weiss. Includes index. ISBN 978-0-9784713-0-9 1. 2. I. Title. Printed and bound in Canada First Edition To the vibrant Jewish community ofDrohobycz, Poland, that was, but is no more To my loved parents Solomon David and Cilia Weiss To my beloved wife Gertrude Weiss To my precious daughters Francie Winograd, Shelley Weiss and Beverly Schwartz To my dearest brother, Leo Weiss, and sister, Erna Kimmel, my soulmates and witnesses to the world gone mad To my most cherished gran children, Abby, Jill, and Richard Winograd; Evan and Erin Laroque, Michael and Lainie Schwartz, With Hope for a Peacefol and Tolerant Future CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................... 11 ACKNOWLEDGMENT ............................................ , ............. 13 I. PERSONAL ODYSSEY My SPIRITUAL JoURNEY ................................. '" ................ 17 INTERVIEW ..................................................................... 51 II. EVIL TAKES ROOT THE VANISHED WORLD: THE GLORY AND DESTRUCTION OF POLISH JEWRy ..........................................................................71 THE VANISHED WORLD PART II: POLES AND JEWS, THEN AND Now .. 85 THE TRAVAILS, TRIUMPHS AND TRAGEDY OF GERMAN JEWRY ....... 99 THE CONDEMNED MASTERS OF THE GHETTOS ... '" ................... 125 POETRY OUT OF THE AsHES SMOKE ....................................................................... -

Refugee Policies from 1933 Until Today: Challenges and Responsibilities

Refugee Policies from 1933 until Today: Challenges and Responsibilities ihra_4_fahnen.indd 1 12.02.2018 15:59:41 IHRA series, vol. 4 ihra_4_fahnen.indd 2 12.02.2018 15:59:41 International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (Ed.) Refugee Policies from 1933 until Today: Challenges and Responsibilities Edited by Steven T. Katz and Juliane Wetzel ihra_4_fahnen.indd 3 12.02.2018 15:59:42 With warm thanks to Toby Axelrod for her thorough and thoughtful proofreading of this publication, to the Ambassador Liviu-Petru Zăpirțan and sta of the Romanian Embassy to the Holy See—particularly Adina Lowin—without whom the conference would not have been possible, and to Katya Andrusz, Communications Coordinator at the Director’s Oce of the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. ISBN: 978-3-86331-392-0 © 2018 Metropol Verlag + IHRA Ansbacher Straße 70 10777 Berlin www.metropol-verlag.de Alle Rechte vorbehalten Druck: buchdruckerei.de, Berlin ihra_4_fahnen.indd 4 12.02.2018 15:59:42 Content Declaration of the Stockholm International Forum on the Holocaust ........................................... 9 About the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) .................................................... 11 Preface .................................................... 13 Steven T. Katz, Advisor to the IHRA (2010–2017) Foreword The International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, the Holy See and the International Conference on Refugee Policies ... 23 omas Michael Baier/Veerle Vanden Daelen Opening Remarks ......................................... 31 Mihnea Constantinescu, IHRA Chair 2016 Opening Remarks ......................................... 35 Paul R. Gallagher Keynote Refugee Policies: Challenges and Responsibilities ........... 41 Silvano M. Tomasi FROM THE 1930s TO 1945 Wolf Kaiser Introduction ............................................... 49 Susanne Heim The Attitude of the US and Europe to the Jewish Refugees from Nazi Germany ....................................... -

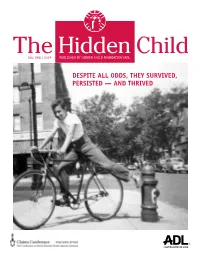

Despite All Odds, They Survived, Persisted — and Thrived Despite All Odds, They Survived, Persisted — and Thrived

The Hidden® Child VOL. XXVII 2019 PUBLISHED BY HIDDEN CHILD FOUNDATION /ADL DESPITE ALL ODDS, THEY SURVIVED, PERSISTED — AND THRIVED DESPITE ALL ODDS, THEY SURVIVED, PERSISTED — AND THRIVED FROM HUNTED ESCAPEE TO FEARFUL REFUGEE: POLAND, 1935-1946 Anna Rabkin hen the mass slaughter of Jews ended, the remnants’ sole desire was to go 3 back to ‘normalcy.’ Children yearned for the return of their parents and their previous family life. For most child survivors, this wasn’t to be. As WEva Fogelman says, “Liberation was not an exhilarating moment. To learn that one is all alone in the world is to move from one nightmarish world to another.” A MISCHLING’S STORY Anna Rabkin writes, “After years of living with fear and deprivation, what did I imagine Maren Friedman peace would bring? Foremost, I hoped it would mean the end of hunger and a return to 9 school. Although I clutched at the hope that our parents would return, the fatalistic per- son I had become knew deep down it was improbable.” Maren Friedman, a mischling who lived openly with her sister and Jewish mother in wartime Germany states, “My father, who had been captured by the Russians and been a prisoner of war in Siberia, MY LIFE returned to Kiel in 1949. I had yearned for his return and had the fantasy that now that Rivka Pardes Bimbaum the war was over and he was home, all would be well. That was not the way it turned out.” Rebecca Birnbaum had both her parents by war’s end. She was able to return to 12 school one month after the liberation of Brussels, and to this day, she considers herself among the luckiest of all hidden children. -

Verfolgen Und Aufklären. Die Erste Generation Der Holocaustforschung

Verfolgen und Aufklären. Die erste Generation der Holocaustforschung Crimes Uncovered. The First Generation of Holocaust Researchers Hans-Christian Jasch Stephan Lehnstaedt (Hrsg./ Editors) Verfolgen und Aufklären. Die erste Generation der Holocaustforschung Crimes Uncovered. The First Generation of Holocaust Researchers Verfolgen und Aufklären. Die erste Generation der Holocaustforschung Crimes Uncovered. The First Generation of Holocaust Researchers Hans-Christian Jasch Stephan Lehnstaedt (Hrsg./ Editors) Gedenk- und Bildungsstätte ISBN: 978-3-86331-467-5 Haus der Wannsee-Konferenz © 2019 Metropol Verlag Ansbacher Str. 70 · D–10777 Berlin www.metropol-verlag.de Alle Rechte vorbehalten Druck: buchdruckerei.de, Berlin Inhalt / Content Seite / Page Hans-Christian Jasch, Stephan Lehnstaedt Emanuel Ringelblum von / by Romina Wiegemann 152 Die erste Generation der Holocaustforschung – Verfolgung, Aufklärung Jacob Robinson von / by Romina Wiegemann 156 und Erinnerung des Völkermords an den europäischen Juden Massimo Adolfo Vitale von / by Nicole Calian 160 The First Generation of Holocaust Research – Persecution, Elucidation Alfred Wiener von / by Barbara Warnock 164 and Remembrance of the Genocide of the European Jews 6 Simon Wiesenthal von / by Romina Wiegemann 168 Joseph Wulf von / by Till Stumpf 172 Stephan Lehnstaedt Vergessene Forscherinnen / Forgotten Female Researchers 176 Galizien vor dem Holocaust. Minderheitenpolitik und ethnische von / by Nora Huberty Gewalt am Beispiel einer historischen Region Ostmitteleuropas Galicia Before the -

Hebcal Diaspora 3987

January 3987 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Rosh Chodesh Sh'vat 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Tu BiShvat Provided by Hebcal.com with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License February 3987 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Rosh Chodesh Adar I Rosh Chodesh Adar I 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Purim Katan Provided by Hebcal.com with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License March 3987 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Rosh Chodesh Adar II Rosh Chodesh Adar II 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Erev Purim 29 30 31 Purim Shushan Purim Provided by Hebcal.com with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License April 3987 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Rosh Chodesh Nisan 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Yom HaAliyah 26 27 28 29 30 Erev Pesach Pesach I Pesach II Pesach III (CH''M) Provided by Hebcal.com with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License May 3987 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 Pesach IV (CH''M) Pesach V (CH''M) 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Pesach VI (CH''M) Pesach VII Pesach VIII 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Yom HaShoah Rosh Chodesh Iyyar Rosh Chodesh Iyyar 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Yom HaZikaron Yom HaAtzma'ut 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Pesach Sheni 31 Lag BaOmer Provided by Hebcal.com with a Creative Commons Attribution -

Yom Hazikaron and Yom Ha'atzmaut – Israel's

YOM HAZIKARON AND YOM HA’ATZMAUT – ISRAEL’S MEMORIAL AND INDEPENDENCE DAYS ABOUT THE DAYS Yom HaZikaron , the day preceding Israel’s Independence Day, was declared by the Israeli Knesset to be Memorial Day for those who lost their lives in the struggles that led to the establishment of the State of Israel and for all military personnel who were killed as members of Israel’s armed forces. Joining these two days together conveys a simple message: Jews all around the world owe the independence and the very existence of the Jewish state to those who sacrificed their lives for it. Yom HaZikaron is different in character and mood from our American Memorial Day. In Israel, for 24 hours, all places of public entertainment are closed. The siren wails twice for two minutes throughout the country, first at 8:00 am to usher in the day, and again at 11:00 am before the public recitation of prayers in the military cemeteries. At the sound of the siren, all traffic and daily activities cease; the entire nation is still. Families are gathered in cemeteries and radio stations broadcast programs devoted to the lives of fallen soldiers. The list grows longer every year as Israel continues to labor for its very survival. Flags in Israel are flown at half mast, and the Yizkor (remembrance) prayer for Israel’s fallen soldiers is recited. May God remember His sons and daughters who exposed themselves to mortal danger in those days of struggle prior to the establishment of the State of Israel and (may He remember) the soldiers of the Israeli Defense Forces who fell in the wars of Israel. -

2020 2021 Judaic Calendar

JUDAIC CALENDAR 5781-5782 2020-2021 “Hello All, My name is Levi Sherman. I live at Reena. I go to day program at Reena. I love Reena. I meet my friends at Reena. I do exercise at Reena. I do colouring.” Levi has been part of the Reena Family for many years. Levi continues to put a smile on everyone’s face …. Dear Reena Staff and Families, It is with great pleasure that we present this year’s Judaic calendar. Inside the pages of the calendar, you can view the many activities enjoyed and celebrated at Reena. All are led by our dedicated staff and volunteers. Naturally, you’ll be able to review details of the coming holidays, important occasions and details that will allow you to observe the Jew- ish holidays. Every calendar, including this one, has a cyclical nature. Holidays and events come and go every year, and this may instill a sense of predictability and calm. During the recent pandemic, Reena staff worked tirelessly to instill a sense of peace for our individuals and to maintain predictable schedules. I hope you will find the calendar useful for yourself , your team, family and beyond. Wishing you all a very successful and healthy year ahead. Bryan Keshen, CEO September 2020 - 5780/5781 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 12 Elul 13 Elul 14 Elul 15 Elul 16 Elul Ki Savo 7:29pm 8:30pm 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 17 Elul 18 Elul 19 Elul 20 Elul 21 Elul 22 Elul 23 Elul Nitzavim-Vayeilech Leil Selichos 7:16pm 8:18pm LABOUR DAY 13 14 15 16 17 18 5781 19 24 Elul 25 Elul 26 Elul 27 Elul 28 Elul 29 Elul 1 Tishrei EREV ROSH HASHANAH ROSH HASHANAH l 7:03pm 8:01pm 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 2 Tishrei 3 Tishrei 4 Tishrei 5 Tishrei 6 Tishrei 7 Tishrei 8 Tishrei ROSH HASHANAH ll FAST OF GEDALIAH Ha’Azinu TASHLICH Fast ends 7:51pm Shabbat Shuvah 7:52pm 8:03pm 6:50pm 27 28 29 30 9 Tishrei 10 Tishrei 11 Tishrei 12 Tishrei EREV YOM KIPPUR YOM KIPPUR YIZKOR WORLD ALZHEIMER’S MONTH September 21: WORLD ALZHEIMER’S DAY 6:47pm 7:48pm ELUL/TISHREI - SEPTEMBER October The sounds of the Shofar were heard throughout Reena during the month of Elul. -

About the Yom's

- Mourning, Joy and Hope!” and Joy Mourning, - “Not just History; Living Memory Living History; just “Not 5, 4, and 28 and 4, 5, Iyar 27, Nissan April 23, May, 1, 2, and 24 24 and 2, 1, May, 23, April Collective Responses to Recent Jewish History Jewish Recent to Responses Collective Yom Yerushaliem) Yom Yom HaAtzmaut, and HaAtzmaut, Yom HaZikaron, Yom HaShoah, (Yom The Yom’s The All about All Fun Facts The flag of Israel was selected in 1948, only 5 months after the state was established. The flag includes two blue stripes on white background with a blue Shield of David (6 pointed star) in the center. The chosen colors blue & white symbolize trust and honesty. On the afternoon of Jerusalem’s liberation, June 7, 1967, Israeli Defense Minister Moshe Dayan made the following statement from the Western Wall: We have united Jerusalem, the divided capital of Israel. We have returned to the holiest of our holy places, never to part from it again. To our Arab neighbors we extend, also at this hour — and with added emphasis at this hour — our hand in peace. And to our Christian and Muslim fellow citizens, we solemnly promise full religious freedom and rights. We did not come to Jerusalem for the sake of other peoples’ holy places, and not to interfere with the adherents of other faiths, but in order to safeguard its entirety, and to live there together with others, in unity. As long as deep within the heart a Jewish soul stirs, and forward to the ends of the East an eye looks out towards Zion, our hope is not yet lost.