Political Prisoners and the Irish Language: a North-South Comparison1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

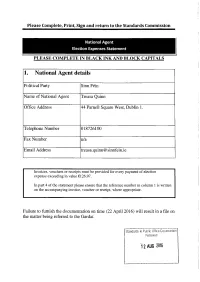

Sinn-Fein-NA-EES.Pdf

Candidate Name Constituency Amount Assigned Total Expenditure on the candidate by the national agent € € 1. Micheal MacDonncha Dublin Bay North 5000 2.Denise Mitchell Dublin Bay North 5000 3.Chris Andrews Dublin Bay South 5000 450.33 4.Mary Lou McDonald Dublin Central 4000 5.Louise O’Reilly Dublin Fingal 8000 2449.33 6. Eoin O’Broin Dublin Mid West 3000 7. Dessie Ellis Dublin North West 3000 8.Cathleen Carney Boud Dublin North West 5000 9.Sorcha Nic Cormaic Dublin Rathdown 5000 10.Aengus Ó Snodaigh Dublin South 3000 Central 11.Màire Devine Dublin South 3000 Central 12. Sean Crowe Dublin South West 3000 13.Sarah Holland Dublin South West 5000 14.Paul Donnelly Dublin West 3000 69.50 15.Shane O’Brien Dun Laoghaire 5000 73.30 16.Caoimhghìn Ó Caoláin Cavan Monaghan 3000 129.45 17.Kathryn Reilly Cavan Monaghan 3000 192.20 18.Pearse Doherty Donegal 3000 19.Pádraig MacLochlainn Donegal 3000 20.Garry Doherty Donegal 3000 21.Annemarie Roche Galway East 5000 22.Trevor O’Clochartaigh Galway West 5000 73.30 23.Réada Cronin Kildare North 5000 24.Patricia Ryan Kildare South 5000 13.75 25.Brian Stanley Laois 3000 255.55 26.Paul Hogan Longford 5000 Westmeath 27.Gerry Adams Louth 3000 28.Imelda Munster Louth 10000 29.Rose Conway Walsh Mayo 10000 560.57 30.Darren O’Rourke Meath East 6000 31.Peadar Tòibìn Meath West 3000 247.57 32.Carol Nolan Offaly 4000 33.Claire Kerrane Roscommon Galway 5000 34.Martin Kenny Sligo Leitrim 3000 193.36 35.Chris MacManus Sligo Leitrim 5000 36.Kathleen Funchion Carlow Kilkenny 5000 37.Noeleen Moran Clare 5000 794.51 38.Pat Buckley Cork East 6000 202.75 39.Jonathan O’Brien Cork North Central 3000 109.95 40.Thomas Gould Cork North Central 5000 109.95 41.Nigel Dennehy Cork North West 5000 42.Donnchadh Cork South Central 3000 O’Laoghaire 43.Rachel McCarthy Cork south West 5000 101.64 44.Martin Ferris Kerry County 3000 188.62 45.Maurice Quinlivan Limerick City 3000 46.Seamus Browne Limerick City 5000 187.11 47.Seamus Morris Tipperary 6000 1428.49 48.David Cullinane Waterford 3000 565.94 49.Johnny Mythen Wexford 10000 50.John Brady Wicklow 5000 . -

The Counter-Aesthetics of Republican Prison Writing

Notes Chapter One Introduction: Taoibh Amuigh agus Faoi Ghlas: The Counter-aesthetics of Republican Prison Writing 1. Gerry Adams, “The Fire,” Cage Eleven (Dingle: Brandon, 1990) 37. 2. Ibid., 46. 3. Pat Magee, Gangsters or Guerillas? (Belfast: Beyond the Pale, 2001) v. 4. David Pierce, ed., Introduction, Irish Writing in the Twentieth Century: A Reader (Cork: Cork University Press, 2000) xl. 5. Ibid. 6. Shiela Roberts, “South African Prison Literature,” Ariel 16.2 (Apr. 1985): 61. 7. Michel Foucault, “Power and Strategies,” Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977, ed. Colin Gordon (New York: Pantheon, 1980) 141–2. 8. In “The Eye of Power,” for instance, Foucault argues, “The tendency of Bentham’s thought [in designing prisons such as the famed Panopticon] is archaic in the importance it gives to the gaze.” In Power/ Knowledge 160. 9. Breyten Breytenbach, The True Confessions of an Albino Terrorist (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1983) 147. 10. Ioan Davies, Writers in Prison (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1990) 4. 11. Ibid. 12. William Wordsworth, “Preface to Lyrical Ballads,” The Norton Anthology of English Literature vol. 2A, 7th edition, ed. M. H. Abrams et al. (New York: W. W. Norton, 2000) 250. 13. Gerry Adams, “Inside Story,” Republican News 16 Aug. 1975: 6. 14. Gerry Adams, “Cage Eleven,” Cage Eleven (Dingle: Brandon, 1990) 20. 15. Wordsworth, “Preface” 249. 16. Ibid., 250. 17. Ibid. 18. Terry Eagleton, The Ideology of the Aesthetic (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1990) 27. 19. W. B. Yeats, Essays and Introductions (New York: Macmillan, 1961) 521–2. 20. Bobby Sands, One Day in My Life (Dublin and Cork: Mercier, 1983) 98. -

“Éire Go Brách” the Development of Irish Republican Nationalism in the 20Th Into the 21St Centuries

“Éire go Brách” The Development of Irish Republican Nationalism in the 20th into the 21st Centuries Alexandra Watson Honors Thesis Dr. Giacomo Gambino Department of Political Science Spring 2020 Watson 2 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Literature Review: Irish Nationalism -- What is it ? 5 A Brief History 18 ‘The Irish Question’ and Early Roots of Irish Republicanism 20 Irish Republicanism and the War for Independence 25 The Anglo Irish Treaty of 1921, Pro-Treaty Republicanism vs. Anti-Treaty Republicanism, and Civil War 27 Early Statehood 32 ‘The Troubles’ and the Good Friday Agreement 36 Why is ‘the North’ Different? 36 ‘The Troubles’ 38 The Good Friday Agreement 40 Contemporary Irish Politics: Irish Nationalism Now? 45 Explaining the Current Political System 45 Competing nationalisms Since the Good Friday Agreement and the Possibility of Unification 46 2020 General Election 47 Conclusions 51 Appendix 54 Acknowledgements 57 Bibliography 58 Watson 3 Introduction In June of 2016, the people of the United Kingdom democratically elected to leave the European Union. The UK’s decision to divorce from the European Union has brought significant uncertainty for the country both in domestic and foreign policy and has spurred a national identity crisis across the United Kingdom. The Brexit negotiations themselves, and the consequences of them, put tremendous pressure on already strained international relationships between the UK and other European countries, most notably their geographic neighbour: the Republic of Ireland. The Anglo-Irish relationship is characterized by centuries of mutual antagonism and the development of Irish national consciousness, which ultimately resulted in the establishment of an autonomous Irish free state in 1922. -

Identity, Authority and Myth-Making: Politically-Motivated Prisoners and the Use of Music During the Northern Irish Conflict, 1962 - 2000

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online Identity, authority and myth-making: Politically-motivated prisoners and the use of music during the Northern Irish conflict, 1962 - 2000 Claire Alexandra Green Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 I, Claire Alexandra Green, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: 29/04/19 Details of collaboration and publications: ‘It’s All Over: Romantic Relationships, Endurance and Loyalty in the Songs of Northern Irish Politically-Motivated Prisoners’, Estudios Irlandeses, 14, 70-82. 2 Abstract. In this study I examine the use of music by and in relation to politically-motivated prisoners in Northern Ireland, from the mid-1960s until 2000. -

Drumcree 4 Standoff: Nationalists Will

UIMH 135 JULY — IUIL 1998 50p (USA $1) Drumcree 4 standoff: Nationalists will AS we went to press the Drumcree standoff was climbdown by the British in its fifth day and the Orange Order and loyalists government. were steadily increasing their campaign of The co-ordinated and intimidation and pressure against the nationalist synchronised attack on ten Catholic churches on the night residents in Portadown and throughout the Six of July 1-2 shows that there is Counties. a guiding hand behind the For the fourth year the brought to a standstill in four loyalist protests. Mo Mowlam British government looks set to days and the Major government is fooling nobody when she acts back down in the face of Orange caved in. the innocent and seeks threats as the Tories did in 1995, The ease with which "evidence" of any loyalist death 1996 and Tony Blair and Mo Orangemen are allowed travel squad involvement. Mowlam did (even quicker) in into Drurncree from all over the Six Counties shows the The role of the 1997. constitutional nationalist complicity of the British army Once again the parties sitting in Stormont is consequences of British and RUC in the standoff. worth examining. The SDLP capitulation to Orange thuggery Similarly the Orangemen sought to convince the will have to be paid by the can man roadblocks, intimidate Garvaghy residents to allow a nationalist communities. They motorists and prevent 'token' march through their will be beaten up by British nationalists going to work or to area. This was the 1995 Crown Forces outside their the shops without interference "compromise" which resulted own homes if they protest from British policemen for in Ian Paisley and David against the forcing of Orange several hours. -

These Are the Future Leaders of Ulster If the St Andrews Agreement Is Endorsed

The Burning Bush—Online article archive These are the future leaders of Ulster if the St Andrews Agreement is endorsed “The Burning Bush” has only two more issues to go after this current edition, before its witness concludes. It has sought to warn its readers of the wickedness and com- promise taking place within “church and state”, since its first edition back in March 1970. The issues facing Christians were comparatively plain and simple back then, or so it seems now on reflection. Today, however, the confusion that we sought to combat McGuinness (far right) in IRA uniform at the funeral of fellow within the ranks of the ecumenical churches and organi- IRA man and close friend Colm sations, seems to have spread to the ranks of those who, Keenan in 1972 over the years, have been engaged in opposing the reli- gious and political sell-out. The reaction to the St Andrews Agreement has shown that to be so. It is an agreement, when stripped of all its legal jargon and political frills, that will place an unrepentant murderer in co-leadership of Northern Ireland. How unthinkable such a notion was back in 1970! Today we are told, it is both thinkable and exceeding wise! In an effort to refocus the minds and hearts of Christians we publish some well- established facts about those whom the St Andrews Agreement would have us choose and submit to and make masters of our destiny and that of our children. By the blessing of God, may a consideration of these facts awaken the slumbering soul of Ulster Protestantism. -

The 1916 Easter Rising Transformed Ireland. the Proclamation of the Irish Republic Set the Agenda for Decades to Come and Led Di

The 1916 Easter Rising transformed Ireland. The Proclamation of the Irish Republic set the agenda for decades to come and led directly to the establishment of an Chéad Dáil Éireann. The execution of 16 leaders, the internment without trial of hundreds of nationalists and British military rule ensured that the people turned to Sinn Féin. In 1917 republican by-election victories, the death on hunger strike of Thomas Ashe and the adoption of the Republic as the objective of a reorganised Sinn Féin changed the course of Irish history. 1916-1917 Pádraig Pearse Ruins of the GPO 1916 James Connolly Detainees are marched to prison after Easter Rising, Thomas Ashe lying in state in Mater Hospital, Dublin, Roger Casement on trial in London over 1800 were rounded up September 1917 Liberty Hall, May 1917, first anniversary of Connolly’s Crowds welcome republican prisoners home from Tipperary IRA Flying Column execution England 1917 Released prisoners welcomed in Dublin 1918 Funeral of Thomas Ashe, September 1917 The British government attempted to impose Conscription on Ireland in 1918. They were met with a united national campaign, culminating in a General Strike and the signing of the anti-Conscription pledge by hundreds of thousands of people. In the General Election of December 1918 Sinn Féin 1918 triumphed, winning 73 of the 105 seats in Ireland. The Anti-Conscription Pledge drawn up at the The Sinn Féin General Election Manifesto which was censored by Taking the Anti-Conscription Pledge on 21 April 1919 Mansion House conference on April 18 1919 the British government when it appeared in the newspapers Campaigning in the General Election, December 1918 Constance Markievicz TD and First Dáil Minister for Labour, the first woman elected in Ireland Sinn Féin postcard 1917 Sinn Féin by-election posters for East Cavan (1918) and Kilkenny City (1917) Count Plunkett, key figure in the building of Sinn Féin 1917/1918 Joseph McGuinness, political prisoner, TD for South Longford The First Dáil Éireann assembled in the Mansion House, Dublin, on 21 January 1919. -

Thatcher, Northern Ireland and Anglo-Irish Relations, 1979-1990

From ‘as British as Finchley’ to ‘no selfish strategic interest’: Thatcher, Northern Ireland and Anglo-Irish Relations, 1979-1990 Fiona Diane McKelvey, BA (Hons), MRes Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences of Ulster University A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Ulster University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2018 I confirm that the word count of this thesis is less than 100,000 words excluding the title page, contents, acknowledgements, summary or abstract, abbreviations, footnotes, diagrams, maps, illustrations, tables, appendices, and references or bibliography Contents Acknowledgements i Abstract ii Abbreviations iii List of Tables v Introduction An Unrequited Love Affair? Unionism and Conservatism, 1885-1979 1 Research Questions, Contribution to Knowledge, Research Methods, Methodology and Structure of Thesis 1 Playing the Orange Card: Westminster and the Home Rule Crises, 1885-1921 10 The Realm of ‘old unhappy far-off things and battles long ago’: Ulster Unionists at Westminster after 1921 18 ‘For God's sake bring me a large Scotch. What a bloody awful country’: 1950-1974 22 Thatcher on the Road to Number Ten, 1975-1979 26 Conclusion 28 Chapter 1 Jack Lynch, Charles J. Haughey and Margaret Thatcher, 1979-1981 31 'Rise and Follow Charlie': Haughey's Journey from the Backbenches to the Taoiseach's Office 34 The Atkins Talks 40 Haughey’s Search for the ‘glittering prize’ 45 The Haughey-Thatcher Meetings 49 Conclusion 65 Chapter 2 Crisis in Ireland: The Hunger Strikes, 1980-1981 -

The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather

Finding a Voice: The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather Macdougall A Thesis in the PhD Humanities Program Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada August 2012 © Heather Macdougall, 2012 ABSTRACT Finding a Voice: The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather Macdougall, Ph.D. Concordia University, 2012 This dissertation investigates the history of film production in the minority language of Irish Gaelic. The objective is to determine what this history reveals about the changing roles of both the national language and national cinema in Ireland. The study of Irish- language film provides an illustrative and significant example of the participation of a minority perspective within a small national cinema. It is also illustrates the potential role of cinema in language maintenance and revitalization. Research is focused on policies and practices of filmmaking, with additional consideration given to film distribution, exhibition, and reception. Furthermore, films are analysed based on the strategies used by filmmakers to integrate the traditional Irish language with the modern medium of film, as well as their motivations for doing so. Research methods included archival work, textual analysis, personal interviews, and review of scholarly, popular, and trade publications. Case studies are offered on three movements in Irish-language film. First, the Irish- language organization Gael Linn produced documentaries in the 1950s and 1960s that promoted a strongly nationalist version of Irish history while also exacerbating the view of Irish as a “private discourse” of nationalism. Second, independent filmmaker Bob Quinn operated in the Irish-speaking area of Connemara in the 1970s; his fiction films from that era situated the regional affiliations of the language within the national context. -

Handbook of Second Level Educational Research: Breaking the S.E.A.L

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Handbook of second level educational research: Breaking the S.E.A.L. Student engagement with archives for learning Author(s) Flynn, Paul; Houlihan, Barry Publication Date 2017-07 Publication Flynn, Paul, & Houlihan, Barry. (2017). Handbook of second Information level educational research: Breaking the S.E.A.L. Student engagement with archives for learning. Galway: NUI Galway. Publisher NUI Galway Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/6687 Downloaded 2021-09-24T14:02:50Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Handbook of Second Level Educational Research Breaking the S.E.A.L. Student Engagement with Archives for Learning, NUI Galway, 2017 Editors: Paul Flynn and Barry Houlihan ISBN: 978-1-908358-56-1 Table of Contents Foreword 7 Introduction 9 Moneenageisha Community College 10 Alanna O’Reilly Deborah Sampson Gannett and Her Role in the Continental Army During the American Revolutionary War. 11 Mitchelle Dupe The Death of Emmett Till and its Effect on American Civil Rights Movement. 11 Andreea Duma Joan Parlea: His Role in the Germany Army Between 1941-1943. 11 Paddy Hogan An Irishmans' Role in The Suez Crisis. 11 Presentation College Headford 12 Michael McLoughlin Trench Warfare in World War 1 13 Ezra Heraty The Gallant Heroics of Pigeons during the Great War 14 Sophie Smith The White Rose Movement 15 Maggie Larson The Hollywood Blacklist: Influences on Film Content 1933-50 16 Diarmaid Conway Michael Cusack – Gaelic Games Pioneer 18 Ciara Varley Emily Hobhouse in the Anglo-Boer War 19 Andrew Egan !3 The Hunger Striking in Irish Republicanism 21 Joey Maguire Michael Cusack 23 Coláiste Mhuire, Ballygar 24 Mártin Quinn The Iranian Hostage Crisis: How the Canadian Embassy Workers Helped to Rescue the Six Escaped Hostages. -

Publications

Publications National Newspapers Evening Echo Irish Examiner Sunday Business Post Evening Herald Irish Field Sunday Independent Farmers Journal Irish Independent Sunday World Irish Daily Star Irish Times Regional Newspapers Anglo Celt Galway City Tribune Nenagh Guardian Athlone Topic Gorey Echo New Ross Echo Ballyfermot Echo Gorey Guardian New Ross Standard Bray People Inish Times Offaly Express Carlow Nationalist Inishowen Independent Offaly Independent Carlow People Kerryman Offaly Topic Clare Champion Kerry’s Eye Roscommon Herald Clondalkin Echo Kildare Nationalist Sligo Champion Connacht Tribune Kildare Post Sligo Weekender Connaught Telegraph Kilkenny People South Tipp Today Corkman Laois Nationalist Southern Star Donegal Democrat Leinster Express Tallaght Echo Donegal News Leinster Leader The Argus Donegal on Sunday Leitrim Observer The Avondhu Donegal People’s Press Letterkenny Post The Carrigdhoun Donegal Post Liffey Champion The Nationalist Drogheda Independent Limerick Chronnicle Tipperary Star Dublin Gazette - City Limerick Leader Tuam Herald Dublin Gazette - North Longford Leader Tullamore Tribune Dublin Gazette - South Lucan Echo Waterford News & Star Dublin Gazette - West Lucan Echo Western People Dundalk Democrat Marine Times Westmeath Examiner Dungarvan Leader Mayo News Westmeath Independent Dungarvan Observer Meath Chronnicle Westmeath Topic Enniscorthy Echo Meath Topic Wexford Echo Enniscorthy Guardian Midland Tribune Wexford People Fingal Independent Munster Express Wicklow People Finn Valley Post Munster Express Magazines -

In Defense of Propaganda: the Republican Response to State

IN DEFENSE OF PROPAGANDA: THE REPUBLICAN RESPONSE TO STATE CREATED NARRATIVES WHICH SILENCED POLITICAL SPEECH DURING THE NORTHERN IRISH CONFLICT, 1968-1998 A thesis presented to The Honors Tutorial College Ohio University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Honors Tutorial College with a Degree of Bachelor of Science in Journalism By Selina Nadeau April 2017 1 This thesis is approved by The Honors Tutorial College and the Department of Journalism Dr. Aimee Edmondson Professor, Journalism Thesis Adviser Dr. Bernhard Debatin Director of Studies, Journalism Dr. Jeremy Webster Dean, Honors Tutorial College 2 Table of Contents 1. History 2. Literature Review 2.1. Reframing the Conflict 2.2.Scholarship about Terrorism in Northern Ireland 2.3.Media Coverage of the Conflict 3. Theoretical Frameworks 3.1.Media Theory 3.2.Theories of Ethnic Identity and Conflict 3.3.Colonialism 3.4.Direct rule 3.5.British Counterterrorism 4. Research Methods 5. Researching the Troubles 5.1.A student walks down the Falls Road 6. Media Censorship during the Troubles 7. Finding Meaning in the Posters from the Troubles 7.1.Claims of Abuse of State Power 7.1.1. Social, political or economic grievances 7.1.2. Criticism of Government Officials 7.1.3. Criticism of the police, army or security forces 7.1.4. Criticism of media or censorship of media 7.2.Calls for Peace 7.2.1. Calls for inclusive all-party peace talks 7.2.2. British withdrawal as the solution 7.3.Appeals to Rights, Freedom, or Liberty 7.3.1. Demands of the Civil Rights Movement 7.3.2.