The Irish Press Coverage of the Troubles in the North from 1968 to 1995

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

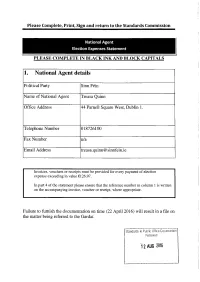

Sinn-Fein-NA-EES.Pdf

Candidate Name Constituency Amount Assigned Total Expenditure on the candidate by the national agent € € 1. Micheal MacDonncha Dublin Bay North 5000 2.Denise Mitchell Dublin Bay North 5000 3.Chris Andrews Dublin Bay South 5000 450.33 4.Mary Lou McDonald Dublin Central 4000 5.Louise O’Reilly Dublin Fingal 8000 2449.33 6. Eoin O’Broin Dublin Mid West 3000 7. Dessie Ellis Dublin North West 3000 8.Cathleen Carney Boud Dublin North West 5000 9.Sorcha Nic Cormaic Dublin Rathdown 5000 10.Aengus Ó Snodaigh Dublin South 3000 Central 11.Màire Devine Dublin South 3000 Central 12. Sean Crowe Dublin South West 3000 13.Sarah Holland Dublin South West 5000 14.Paul Donnelly Dublin West 3000 69.50 15.Shane O’Brien Dun Laoghaire 5000 73.30 16.Caoimhghìn Ó Caoláin Cavan Monaghan 3000 129.45 17.Kathryn Reilly Cavan Monaghan 3000 192.20 18.Pearse Doherty Donegal 3000 19.Pádraig MacLochlainn Donegal 3000 20.Garry Doherty Donegal 3000 21.Annemarie Roche Galway East 5000 22.Trevor O’Clochartaigh Galway West 5000 73.30 23.Réada Cronin Kildare North 5000 24.Patricia Ryan Kildare South 5000 13.75 25.Brian Stanley Laois 3000 255.55 26.Paul Hogan Longford 5000 Westmeath 27.Gerry Adams Louth 3000 28.Imelda Munster Louth 10000 29.Rose Conway Walsh Mayo 10000 560.57 30.Darren O’Rourke Meath East 6000 31.Peadar Tòibìn Meath West 3000 247.57 32.Carol Nolan Offaly 4000 33.Claire Kerrane Roscommon Galway 5000 34.Martin Kenny Sligo Leitrim 3000 193.36 35.Chris MacManus Sligo Leitrim 5000 36.Kathleen Funchion Carlow Kilkenny 5000 37.Noeleen Moran Clare 5000 794.51 38.Pat Buckley Cork East 6000 202.75 39.Jonathan O’Brien Cork North Central 3000 109.95 40.Thomas Gould Cork North Central 5000 109.95 41.Nigel Dennehy Cork North West 5000 42.Donnchadh Cork South Central 3000 O’Laoghaire 43.Rachel McCarthy Cork south West 5000 101.64 44.Martin Ferris Kerry County 3000 188.62 45.Maurice Quinlivan Limerick City 3000 46.Seamus Browne Limerick City 5000 187.11 47.Seamus Morris Tipperary 6000 1428.49 48.David Cullinane Waterford 3000 565.94 49.Johnny Mythen Wexford 10000 50.John Brady Wicklow 5000 . -

The Failure of an Irish Political Party

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DCU Online Research Access Service 1 Journalism in Ireland: The Evolution of a Discipline Mark O’Brien While journalism in Ireland had a long gestation, the issues that today’s journalists grapple with are very much the same that their predecessors had to deal with. The pressures of deadlines and news gathering, the reliability and protection of sources, dealing with patronage and pressure from the State, advertisers and prominent personalities, and the fear of libel and State regulation were just as much a part of early journalism as they are today. What distinguished early journalism was the intermittent nature of publication and the rapidity with which newspaper titles appeared and disappeared. The Irish press had a faltering start but by the early 1800s some of the defining characteristics of contemporary journalism – specific skill sets, shared professional norms and professional solidarity – had emerged. In his pioneering work on the history of Irish newspapers, Robert Munter noted that, although the first newspaper printed in Ireland, The Irish Monthly Mercury (which carried accounts of Oliver Cromwell’s campaign in Ireland) appeared in December 1649 it was not until February 1659 that the first Irish newspaper appeared. An Account of the Chief Occurrences of Ireland, Together with some Particulars from England had a regular publication schedule (it was a weekly that published at least five editions), appeared under a constant name and was aimed at an Irish, rather than a British, readership. It, in turn, was followed in January 1663 by Mercurius Hibernicus, which carried such innovations as issue numbers and advertising. -

These Are the Future Leaders of Ulster If the St Andrews Agreement Is Endorsed

The Burning Bush—Online article archive These are the future leaders of Ulster if the St Andrews Agreement is endorsed “The Burning Bush” has only two more issues to go after this current edition, before its witness concludes. It has sought to warn its readers of the wickedness and com- promise taking place within “church and state”, since its first edition back in March 1970. The issues facing Christians were comparatively plain and simple back then, or so it seems now on reflection. Today, however, the confusion that we sought to combat McGuinness (far right) in IRA uniform at the funeral of fellow within the ranks of the ecumenical churches and organi- IRA man and close friend Colm sations, seems to have spread to the ranks of those who, Keenan in 1972 over the years, have been engaged in opposing the reli- gious and political sell-out. The reaction to the St Andrews Agreement has shown that to be so. It is an agreement, when stripped of all its legal jargon and political frills, that will place an unrepentant murderer in co-leadership of Northern Ireland. How unthinkable such a notion was back in 1970! Today we are told, it is both thinkable and exceeding wise! In an effort to refocus the minds and hearts of Christians we publish some well- established facts about those whom the St Andrews Agreement would have us choose and submit to and make masters of our destiny and that of our children. By the blessing of God, may a consideration of these facts awaken the slumbering soul of Ulster Protestantism. -

The 1916 Easter Rising Transformed Ireland. the Proclamation of the Irish Republic Set the Agenda for Decades to Come and Led Di

The 1916 Easter Rising transformed Ireland. The Proclamation of the Irish Republic set the agenda for decades to come and led directly to the establishment of an Chéad Dáil Éireann. The execution of 16 leaders, the internment without trial of hundreds of nationalists and British military rule ensured that the people turned to Sinn Féin. In 1917 republican by-election victories, the death on hunger strike of Thomas Ashe and the adoption of the Republic as the objective of a reorganised Sinn Féin changed the course of Irish history. 1916-1917 Pádraig Pearse Ruins of the GPO 1916 James Connolly Detainees are marched to prison after Easter Rising, Thomas Ashe lying in state in Mater Hospital, Dublin, Roger Casement on trial in London over 1800 were rounded up September 1917 Liberty Hall, May 1917, first anniversary of Connolly’s Crowds welcome republican prisoners home from Tipperary IRA Flying Column execution England 1917 Released prisoners welcomed in Dublin 1918 Funeral of Thomas Ashe, September 1917 The British government attempted to impose Conscription on Ireland in 1918. They were met with a united national campaign, culminating in a General Strike and the signing of the anti-Conscription pledge by hundreds of thousands of people. In the General Election of December 1918 Sinn Féin 1918 triumphed, winning 73 of the 105 seats in Ireland. The Anti-Conscription Pledge drawn up at the The Sinn Féin General Election Manifesto which was censored by Taking the Anti-Conscription Pledge on 21 April 1919 Mansion House conference on April 18 1919 the British government when it appeared in the newspapers Campaigning in the General Election, December 1918 Constance Markievicz TD and First Dáil Minister for Labour, the first woman elected in Ireland Sinn Féin postcard 1917 Sinn Féin by-election posters for East Cavan (1918) and Kilkenny City (1917) Count Plunkett, key figure in the building of Sinn Féin 1917/1918 Joseph McGuinness, political prisoner, TD for South Longford The First Dáil Éireann assembled in the Mansion House, Dublin, on 21 January 1919. -

Thatcher, Northern Ireland and Anglo-Irish Relations, 1979-1990

From ‘as British as Finchley’ to ‘no selfish strategic interest’: Thatcher, Northern Ireland and Anglo-Irish Relations, 1979-1990 Fiona Diane McKelvey, BA (Hons), MRes Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences of Ulster University A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Ulster University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2018 I confirm that the word count of this thesis is less than 100,000 words excluding the title page, contents, acknowledgements, summary or abstract, abbreviations, footnotes, diagrams, maps, illustrations, tables, appendices, and references or bibliography Contents Acknowledgements i Abstract ii Abbreviations iii List of Tables v Introduction An Unrequited Love Affair? Unionism and Conservatism, 1885-1979 1 Research Questions, Contribution to Knowledge, Research Methods, Methodology and Structure of Thesis 1 Playing the Orange Card: Westminster and the Home Rule Crises, 1885-1921 10 The Realm of ‘old unhappy far-off things and battles long ago’: Ulster Unionists at Westminster after 1921 18 ‘For God's sake bring me a large Scotch. What a bloody awful country’: 1950-1974 22 Thatcher on the Road to Number Ten, 1975-1979 26 Conclusion 28 Chapter 1 Jack Lynch, Charles J. Haughey and Margaret Thatcher, 1979-1981 31 'Rise and Follow Charlie': Haughey's Journey from the Backbenches to the Taoiseach's Office 34 The Atkins Talks 40 Haughey’s Search for the ‘glittering prize’ 45 The Haughey-Thatcher Meetings 49 Conclusion 65 Chapter 2 Crisis in Ireland: The Hunger Strikes, 1980-1981 -

A Protestant Paper for a Protestant People: the Irish Times and the Southern Irish Minority

Irish Communication Review Volume 12 Issue 1 Article 5 January 2010 A Protestant Paper for a Protestant People: The Irish Times and the Southern Irish Minority Ian d’Alton Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/icr Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons Recommended Citation d’Alton, Ian (2010) "A Protestant Paper for a Protestant People: The Irish Times and the Southern Irish Minority," Irish Communication Review: Vol. 12: Iss. 1, Article 5. doi:10.21427/D7TT5T Available at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/icr/vol12/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Current Publications at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Irish Communication Review by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License A PROTESTANT PAPER FOR A PROTESTANT PEOPLE: The Irish Times and the southern Irish minority Ian d’Alton WE IRISH PROTESTANTS have always had a reputation for appreciating the minutiae of social distinction. Often invisible to the outsider, this extended to such as our dogs, our yachts and, of course, our newspapers. My paternal grandmother was no exception. Her take on the relative pecking order of the Irish dailies was that one got one’s news and views from the Irish Times, one lit the fire with the Irish Independent, and as for the Irish Press – ah! Delicacy forbids me to go into details, but suffice it to say that it involved cutting it into appropriate squares, and hanging these in the smallest room of the house! In this paper I set the scene, as it were: to examine those who formed the Times’ perceived audience for much of its existence – Irish Protestants, in particular those who were citizens of the Free State and the early Republic. -

Irish Political Review, January, 2011

Of Morality & Corruption Ireland & Israel Another PD Budget! Brendan Clifford Philip O'Connor Labour Comment page 16 page 23 back page IRISH POLITICAL REVIEW January 2011 Vol.26, No.1 ISSN 0790-7672 and Northern Star incorporating Workers' Weekly Vol.25 No.1 ISSN 954-5891 Economic Mindgames Irish Budget 2011 To Default or Not to Default? that is the question facing the Irish democracy at present. In normal circumstances this would be Should Ireland become the first Euro-zone country to renege on its debts? The bank debt considered an awful budget. But the cir- in question has largely been incurred by private institutions of the capitalist system, cumstances are not normal. Our current which. made plenty money for themselves when times were good—which adds a budget deficit has ballooned to 11.6% of piquancy to the choice ahead. GDP (Gross Domestic Product) excluding As Irish Congress of Trade Unions General Secretary David Begg has pointed out, the bank debt (over 30% when the once-off Banks have been reckless. The net foreign debt of the Irish banking sector was 10% of bank recapitalisation is taken into account). Gross Domestic Product in 2003. By 2008 it had risen to 60%. And he adds: "They lied Our State debt to GDP is set to increase to about their exposure" (Irish Times, 13.12.10). just over 100% in the coming years. A few When the world financial crisis sapped investor confidence, and cut off the supply of years ago our State debt was one of the funds to banks across the world, the Irish banks threatened to become insolvent as private lowest, but now it is one of the highest, institutions. -

The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather

Finding a Voice: The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather Macdougall A Thesis in the PhD Humanities Program Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada August 2012 © Heather Macdougall, 2012 ABSTRACT Finding a Voice: The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather Macdougall, Ph.D. Concordia University, 2012 This dissertation investigates the history of film production in the minority language of Irish Gaelic. The objective is to determine what this history reveals about the changing roles of both the national language and national cinema in Ireland. The study of Irish- language film provides an illustrative and significant example of the participation of a minority perspective within a small national cinema. It is also illustrates the potential role of cinema in language maintenance and revitalization. Research is focused on policies and practices of filmmaking, with additional consideration given to film distribution, exhibition, and reception. Furthermore, films are analysed based on the strategies used by filmmakers to integrate the traditional Irish language with the modern medium of film, as well as their motivations for doing so. Research methods included archival work, textual analysis, personal interviews, and review of scholarly, popular, and trade publications. Case studies are offered on three movements in Irish-language film. First, the Irish- language organization Gael Linn produced documentaries in the 1950s and 1960s that promoted a strongly nationalist version of Irish history while also exacerbating the view of Irish as a “private discourse” of nationalism. Second, independent filmmaker Bob Quinn operated in the Irish-speaking area of Connemara in the 1970s; his fiction films from that era situated the regional affiliations of the language within the national context. -

Charles Trevelyan, John Mitchel and the Historiography of the Great Famine Charles Trevelyan, John Mitchel Et L’Historiographie De La Grande Famine

Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique French Journal of British Studies XIX-2 | 2014 La grande famine en irlande, 1845-1851 Charles Trevelyan, John Mitchel and the historiography of the Great Famine Charles Trevelyan, John Mitchel et l’historiographie de la Grande Famine Christophe Gillissen Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/rfcb/281 DOI: 10.4000/rfcb.281 ISSN: 2429-4373 Publisher CRECIB - Centre de recherche et d'études en civilisation britannique Printed version Date of publication: 1 September 2014 Number of pages: 195-212 ISSN: 0248-9015 Electronic reference Christophe Gillissen, “Charles Trevelyan, John Mitchel and the historiography of the Great Famine”, Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique [Online], XIX-2 | 2014, Online since 01 May 2015, connection on 21 September 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/rfcb/281 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ rfcb.281 Revue française de civilisation britannique est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Charles Trevelyan, John Mitchel and the historiography of the Great Famine Christophe GILLISSEN Université de Caen – Basse Normandie The Great Irish Famine produced a staggering amount of paperwork: innumerable letters, reports, articles, tables of statistics and books were written to cover the catastrophe. Yet two distinct voices emerge from the hubbub: those of Charles Trevelyan, a British civil servant who supervised relief operations during the Famine, and John Mitchel, an Irish nationalist who blamed London for the many Famine-related deaths.1 They may be considered as representative to some extent, albeit in an extreme form, of two dominant trends within its historiography as far as London’s role during the Famine is concerned. -

The Irish Times - Mon, Sep 29, 2008

Adams directs call for truth commission to republicans - The Irish Times - Mon, Sep 29, 2008 US Elections ● Full coverage of the US Presidential undefined 11 °C Dublin » RSS Feeds Site Index election Ireland World CampaignSunsetThe Irishyear on ofTimes trailthe living property 2008 clock cheaply boomSupplements DenisFrankAUDIOHow to Staunton'sMcDonald liveSLIDESHOW: on just andUS a poundelectionKathy The refurbished aSheridan dayblog In Depth followIrish Times the story clock of has a millionaire been unveiled Ferrari- at Other drivingthe newspaper's property developer office at the junction of Today's Paper Tara Street and Townsend Street in Dublin ● Home » ● Ireland » ● In the North » ADVERTISEMENT ● Email to a friend ● Email to Author ● Print ● RSS ● Text Size: Latest » Monday, September 29, 2008 ● 14:23 Adams directs call for truth commission to republicans Zimbabwe unity government close to formation ● 14:19 Injuries Board says insurance hike not justified ● GERRY MORIARTY 14:11 Irish stocks see sharpest fall in more than 20 years SINN FÉIN president Gerry Adams has called for the creation of an independent international truth commission to deal with the legacy of ● 14:10 the Troubles, in a message directed specifically at Sinn Féin and IRA members. Bush says bailout will 'restore strength' ● 14:01 Mr Adams has used the current edition of the republican weekly newspaper, An Phoblacht to back the setting up of a truth commission. Mr Survey finds 40% favour tax hike to pay for services Adams does not specifically state that the IRA must co-operate with such a body, but it appears implicit in one of the nine principles which ● 14:00 'Sacked' employees hold protest in Dublin Sinn Féin proposes should underpin an "effective truth recovery process". -

DUBLIN CITY UNIVERSITY School of Communications the IRISH

DUBLIN CITY UNIVERSITY School of Communications THE IRISH PRESS AND POPULISM IN IRELAND Thesis submitted to Dublin City University m candidacy for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Catherine Curran December 1994 DECLARAIION I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of Doctor of Philosophy is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work Signed Signed Date Signed Date fd ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the following people, whose advice, support and encouragement were essential to the completion of this work My supervisors, Dr Paschal Preston, whose endless patience, time and energy were much appreciated, and Dr Luke Gibbons, who provided valuable source material m the initial stages of the research Professor Desmond Bell, University of Ulster, who stimulated my interest m political economy of the media and encouraged me to undertake further research in the area My fellow postgraduates and colleagues, Jean O'Halloran, Des McGumness, and Sharon Burke The School of Communications, Dublin City University, which provided me with the necessary research funding and all the facilities I required Tim Pat Coogan, Douglas Gageby, Dr Noel Browne and Michael Mills, who granted me interviews and Michael O'Toole and Sean Purcell at the Irish Press who provided many helpful suggestions The staff of the circulation departments of the Irish Press and the -

Michael Collins: Patriot Hero Or 41 Counterrevolutionary? Kieran Allen

Michael Collins: patriot hero or 41 counterrevolutionary? Kieran Allen ichael Collins is a Fine Gael hero. Each year its auxiliary forces in Ireland. One of the most famous young Fine Gael members from across the episodes of the Irish War of Independence was the country travel to Béal na Bláth in County Cork elimination of The Cairo Gang. This was an elite unit where Collins was killed by republican forces who were formed by British military intelligence with Mon August 22 1922 during the Civil War. The annual the aim of assassinating republican leaders. They commemoration for Collins features Fine Gael luminaries arrived in Ireland in September 1920 and within weeks or those who share their outlook. In 2018, for example, shot dead a republican activist from Limerick, John the current Minister for Agriculture, Michael Creed, Lynch, as he lay in his bed. They also came close to got carried away with himself and referred to the site of killing Dan Breen and Sean Tracy, the instigators of the Collins’ execution as a ‘Gaelic Calvary’.1 Having recovered Soloheadbeg attack that set off the War of Independence. from this emotional spasm, he went on, like most of his Michael Collins had established his own squad of armed Fine Gael predecessors, to make a banal speech about operatives within the republican forces and gave the current Irish political life, laced with odd quotes from orders for the execution of the Cairo Gang. One of his Collins himself. Fine Gael’s cult of Collins also includes biographers, James MacKay takes up the story.