Hoofdartikel Defining Neo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluation of Karun River Water Quality Scenarios Using Simulation Model Results

Available online at http://www.ijabbr.com International journal of Advanced Biological and Biomedical Research Volume 2, Issue 2, 2014: 339-358 Evaluation of Karun River Water Quality Scenarios Using Simulation Model Results Mohammad Bagherian Marzouni a*, Ali Mohammad Akhoundalib, Hadi Moazedc, Nematollah Jaafarzadehd,e, Javad Ahadianf, Houshang Hasoonizadehg a Master Science of Civil & Environmental Eng, Faculty of Water Science Eng, Shahid Chamran University Of Ahwaz b Alimohammad Akhoondali, Professor of Water Eng, Faculty of Water Science Eng, Shahid Chamran University Of Ahwaz c Professor of Civil & Environmental Eng, Faculty of Water Science Eng, Shahid Chamran University Of Ahwaz d Environmental Technology Research Center, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran e School of Health, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran. f Assistant Professor of Water Eng, Faculty of Water Science Eng, Shahid Chamran University Of Ahwaz g Vice Basic Studies and Comprehensive Plans for Water Resources. Khuzestan Water and Power Authority. *Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT Karun River is the largest and most watery river in Iran. This river is the longest river which located just inside Iran and Ahvaz Metropolis drinking water supplied from Karun River as well (fa.alalam.ir). Karun River as the main source of water treatment plants in Ahvaz, like most surface waters affected by various contaminants which caused changes in water quality of the river (www.aww.co.ir). Causes such as constructing several dams at upstream river, withdrawal of water from the upstream to the needs of other regions of Iran, exposure of various industries along the river and discharge of industrial and urban sewage into the river, seen that today this river is deteriorating rapidly, qua today is the depth of river reach to 1 m with a high concentration of pollutants (www.tasnimnews.com). -

Of Khuzestan Province, Southwestern Iran

Archive of SID Persian J. Acarol., 2018, Vol. 7, No. 4, pp. 323–344. http://dx.doi.org/10.22073/pja.v7i4.38663 Journal homepage: http://www.biotaxa.org/pja Article Some mesostigmatic mites (Acari: Parasitiformes) of Khuzestan province, southwestern Iran Sara Farahi1, Parviz Shishehbor1 and Alireza Nemati2 1. Department of Plant Protection, Faculty of Agriculture, Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, Ahvaz, Iran; E-mails: [email protected], [email protected] 2. Department of Plant Protection, Faculty of Agriculture, Shahrekord University, Shahrekord, Iran; E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Animal droppings constitute an ephemeral habitat where specialized invertebrate communities including significant abundance of mites live together. In order to study the Mesostigmata mites associated with manure, samples were taken from different manure types of domestic animals and poultry in Ahvaz and its vicinity in Khuzestan Province, southwestern of Iran, over a period of two years (2015-2017). Here we report 20 species belonging to eight families of Mesostigmata, among which 14 species are new records for the fauna of Khuzestan Province. The genus and species Leitneria pugio (Karg, 1961) is newly recorded from Iran. The genus and species were previously only recorded in Europe. Also, Uroobovella varians Hirschmann & Zirngiebl-Nicol, 1962 is recorded for the first time from Iran based on deutonymph stage. We further provide collection data for each species along with a key for known Iranian species of the genus Uroobovella. KEY WORDS: Mesostigmata; Manure-inhabiting mites; Uroobovella; Ahvaz; Iran. PAPER INFO.: Received: 9 May 2018, Accepted: 10 August 2018, Published: 15 October 2018 INTRODUCTION Animal manures possess a rich fauna of arthropods including significant abundance of mites. -

Evaluation of Ecology, Land Uses in Different Parts and the State of the Land Uses' Per Capita of Ahwaz City

Open Journal of Ecology, 2016, 6, 288-302 Published Online May 2016 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/oje http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/oje.2016.66029 Evaluation of Ecology, Land Uses in Different Parts and the State of the Land Uses’ per Capita of Ahwaz City Bahman Bahadori*, Vladimir Boynagryan Department of National Geography, College of Geography and Geology, Yerevan State University, Yerevan, Armenia Received 5 April 2016; accepted 9 May 2016; published 12 May 2016 Copyright © 2016 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract There has been a progressively rivalry among different cities for attaining development oppor- tunities and attraction of economic and social capitals in the recent years. In this universal rivalry, the quality of spaces and urban design are considered as key factors for evaluating cities. There- fore, in this research in order to comprehend the spatial deficiency of the public welfare services in different regions of Ahwaz city, issues such as land uses in different parts of the city, the state and per capita of land uses in the city and comparison of the current land uses with per capita of Comprehensive Plan approved in 1988 are analyzed. Also, evaluation and comparison of the land uses distribution state in different parts of Ahwaz in form of different regions of the city, popula- tion distribution in those regions, residential spaces distribution in the regions, commercial spac- es distribution in the regions, educational spaces distribution in the regions, religious, sanitary and therapeutic, athletic, administrative spaces, green spaces and other spaces distribution in the different regions are also evaluated in this research. -

Mayors for Peace Member Cities 2021/10/01 平和首長会議 加盟都市リスト

Mayors for Peace Member Cities 2021/10/01 平和首長会議 加盟都市リスト ● Asia 4 Bangladesh 7 China アジア バングラデシュ 中国 1 Afghanistan 9 Khulna 6 Hangzhou アフガニスタン クルナ 杭州(ハンチォウ) 1 Herat 10 Kotwalipara 7 Wuhan ヘラート コタリパラ 武漢(ウハン) 2 Kabul 11 Meherpur 8 Cyprus カブール メヘルプール キプロス 3 Nili 12 Moulvibazar 1 Aglantzia ニリ モウロビバザール アグランツィア 2 Armenia 13 Narayanganj 2 Ammochostos (Famagusta) アルメニア ナラヤンガンジ アモコストス(ファマグスタ) 1 Yerevan 14 Narsingdi 3 Kyrenia エレバン ナールシンジ キレニア 3 Azerbaijan 15 Noapara 4 Kythrea アゼルバイジャン ノアパラ キシレア 1 Agdam 16 Patuakhali 5 Morphou アグダム(県) パトゥアカリ モルフー 2 Fuzuli 17 Rajshahi 9 Georgia フュズリ(県) ラージシャヒ ジョージア 3 Gubadli 18 Rangpur 1 Kutaisi クバドリ(県) ラングプール クタイシ 4 Jabrail Region 19 Swarupkati 2 Tbilisi ジャブライル(県) サルプカティ トビリシ 5 Kalbajar 20 Sylhet 10 India カルバジャル(県) シルヘット インド 6 Khocali 21 Tangail 1 Ahmedabad ホジャリ(県) タンガイル アーメダバード 7 Khojavend 22 Tongi 2 Bhopal ホジャヴェンド(県) トンギ ボパール 8 Lachin 5 Bhutan 3 Chandernagore ラチン(県) ブータン チャンダルナゴール 9 Shusha Region 1 Thimphu 4 Chandigarh シュシャ(県) ティンプー チャンディーガル 10 Zangilan Region 6 Cambodia 5 Chennai ザンギラン(県) カンボジア チェンナイ 4 Bangladesh 1 Ba Phnom 6 Cochin バングラデシュ バプノム コーチ(コーチン) 1 Bera 2 Phnom Penh 7 Delhi ベラ プノンペン デリー 2 Chapai Nawabganj 3 Siem Reap Province 8 Imphal チャパイ・ナワブガンジ シェムリアップ州 インパール 3 Chittagong 7 China 9 Kolkata チッタゴン 中国 コルカタ 4 Comilla 1 Beijing 10 Lucknow コミラ 北京(ペイチン) ラクノウ 5 Cox's Bazar 2 Chengdu 11 Mallappuzhassery コックスバザール 成都(チォントゥ) マラパザーサリー 6 Dhaka 3 Chongqing 12 Meerut ダッカ 重慶(チョンチン) メーラト 7 Gazipur 4 Dalian 13 Mumbai (Bombay) ガジプール 大連(タァリィェン) ムンバイ(旧ボンベイ) 8 Gopalpur 5 Fuzhou 14 Nagpur ゴパルプール 福州(フゥチォウ) ナーグプル 1/108 Pages -

Page 1 of 27 PODOCES, 2007, 2(2): 77-96 a Century of Breeding Bird Assessment by Western Travellers in Iran, 1876–1977 - Appendix 1 C.S

PODOCES, 2007, 2(2): 77-96 A century of breeding bird assessment by western travellers in Iran, 1876–1977 - Appendix 1 C.S. ROSELAAR and M. ALIABADIAN Referenced bird localities in Iran x°.y'N x°.y'E °N °E Literature reference province number Ab Ali 35.46 51.58 35,767 51,967 12 Tehran Abadan 30.20 48.15 30,333 48,250 33, 69 Khuzestan Abadeh 31.06 52.40 31,100 52,667 01 Fars Abasabad 36.44 51.06 36,733 51,100 18, 63 Mazandaran Abasabad (nr Emamrud) 36.33 55.07 36,550 55,117 20, 23-26, 71-78 Semnan Abaz - see Avaz Khorasan Abbasad - see Abasabad Semnan Abdolabad ('Abdul-abad') 35.04 58.47 35,067 58,783 86, 88, 96-99 Khorasan Abdullabad [NE of Sabzevar] * * * * 20, 23-26, 71-78 Khorasan Abeli - see Ab Ali Tehran Abiz 33.41 59.57 33,683 59,950 87, 89, 90, 91, 94, 96-99 Khorasan Abr ('Abar') 36.43 55.05 36,717 55,083 37, 40, 84 Semnan Abr pass 36.47 55.00 36,783 55,000 37, 40, 84 Semnan/Golestan Absellabad - see Afzalabad Sistan & Baluchestan Absh-Kushta [at c.: ] 29.35 60.50 29,583 60,833 87, 89, 91, 96-99 Sistan & Baluchestan Abu Turab 33.51 59.36 33,850 59,600 86, 88, 96-99 Khorasan Abulhassan [at c.:] 32.10 49.10 32,167 49,167 20, 23-26, 71-78 Khuzestan Adimi 31.07 61.24 31,117 61,400 90, 94, 96-99 Sistan & Baluchestan Afzalabad 30.56 61.19 30,933 61,317 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, Sistan & Baluchestan 94, 96-99 Aga-baba 36.19 49.36 36,317 49,600 92, 96-99 Qazvin Agulyashker/Aguljashkar/Aghol Jaskar 31.38 49.40 31,633 49,667 92, 96-99 Khuzestan [at c.: ] Ahandar [at c.: ] 32.59 59.18 32,983 59,300 86, 88, 96-99 Khorasan Ahangar Mahalleh - see Now Mal Golestan Ahangaran 33.25 60.12 33,417 60,200 87, 89, 91, 96-99 Khorasan Ahmadabad 35.22 51.13 35,367 51,217 12, 41 Tehran Ahvaz (‘Ahwaz’) 31.20 48.41 31,333 48,683 20, 22, 23-26, 33, 49, 67, Khuzestan 69, 71-78, 80, 92, 96-99 Airabad - see Kheyrabad (nr Turkmen. -

Characteristics of Direct Human Impacts on the Rivers Karun and Dez in Lowland South-West Iran and Their Interactions with Earth Surface Movements

© 2016, Elsevier. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Characteristics of direct human impacts on the rivers Karun and Dez in lowland south-west Iran and their interactions with earth surface movements Kevin P. Woodbridge, Daniel R. Parsons, Vanessa M. A. Heyvaert, Jan Walstra, Lynne E. Frostick Abstract Two of the primary external factors influencing the variability of major river systems, over river reach scales, are human activities and tectonics. Based on the rivers Karun and Dez in south-west Iran, this paper presents an analysis of the geomorphological responses of these major rivers to ancient human modifications and tectonics. Direct human modifications can be distinguished by both modern constructions and ancient remnants of former constructions that can leave a subtle legacy in a suite of river characteristics. For example, the ruins of major dams are characterised by a legacy of channel widening to 100's up to c. 1000 m within upstream zones that can stretch to channel distances of many kilometres upstream of former dam sites, whilst the legacy of major, ancient, anthropogenic river channel straightening can also be distinguished by very low channel sinuosities over long lengths of the river course. Tectonic movements in the region are mainly associated with young and emerging folds with NW–SE and N–S trends and with a long structural lineament oriented E–W. These earth surface movements can be shown to interact with both modern and ancient human impacts over similar timescales, with the types of modification and earth surface motion being distinguishable. -

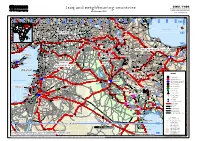

Iraq and Neighbouring Countries Geographic Information and Mapping Unit Population and Geographic Data Section As of November 2003 Email : [email protected]

GIMU / PGDS Iraq and neighbouring countries Geographic Information and Mapping Unit Population and Geographic Data Section As of November 2003 Email : [email protected] Haymana )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) Goradiz ))) )))) Akpinar )))) )))) Tecer )))) Sincan )))) ))) Bank ))) Cheleken )))) )))) )))) ))) ))) )))) )))) )))) Akbenli )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) ))) )))) )))) )))) )))) Sarkisla )))) )))) Hinis ))) Neftechala )))) )))) )))) )))) ))) Karacaoren )))) )))) )))) 33° E 34° E 35° E 36° E )))) 37° E 38° E 39° E 40° E 41° E 42° E 43° E 44° E 45° E 46° E 47° E 48° E 49° E 50° E 51° E 52° E 53° E )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) Uzunlu)))) )))) )))) )))) )))) Caylar )))) )))) )))) )))) Kangal )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) ))) )))) )))) )))) Karaoglan Nakhichevan' ))) ))) ))) )))) )))) )))) )))) ))) ))) Dzhalilabad )))) )))) )))) )))) ))) )))) )))) )))) UU ))) )))) Seker )))) Varto )))) UU ))) ))) )))) )))) UU ))) ))) )))) )))) UU ))) ))) )))) UU ))) ))) )))) UU ))) ))) )))) )))) UU ))) ))) Kirsehir )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) Kadzharan ))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) ))) Prishib )))) )))) )))) )))) Hozat)))) Tunceli )))) Sancak )))) ))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) ))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) Bulanik Paraga ))) )))) )))) )))) Horan )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) Arapkir )))) )))) )))) )))) ))) )))) )))) )))) Ercis )))) )))) ))) Masally )))) )))) )))) )))) 39° N )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) ))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) )))) -

Application of Weather Forecasts in Farm Management Decisions: the Case of Iran

J. Agr. Sci. Tech. (2021) Vol. 23(3): 487-498 Application of Weather Forecasts in Farm Management Decisions: The Case of Iran L. Parsi1 and H. Maleksaeidi1* ABSTRACT Weather forecasts have potential for improving adaptation and resilience of agricultural systems to climate changes; however, there is still uncertainty on the factors affecting the use of this information in farm management decisions. This survey study was conducted on the application of weather information by 213 farmers selected through a stratified random sampling technique in 21 rural areas of Veys, in Khuzestan Province. The results indicated that perception of the reliability of weather information providers, availability of weather forecast information, self-efficacy, and subjective norm were the key drivers for using weather forecast information in the farm management decisions. Based on the results, confidence to the information providers was low among farmers. In addition, social norm about using weather information in practice was not strong in the study area. The results of the study highlighted the need for improving beliefs and values of farmers and their communities about the importance of using weather forecast information for adaptation to climate change. Keywords: Adaptation to climate change, Agricultural decision making, Weather threats. INTRODUCTION live in the arid and semi-arid regions of developing countries and are vulnerable to Agricultural production is significantly climate change due to lack of facilities affected by extreme temperature events (Biglari et al., 2019; Erena et al., 2019; (Jamshidi et al., 2018; Bijani et al., 2017; Trinh et al., 2018; Kumar et al., 2016; Hatfield and Prueger, 2015; Zhang et al., Maleksaeidi and Karami, 2013; Altieri and 2017; Chen et al., 2016), the variation in the Nicholls, 2017). -

Podoces 2 2 Western Travellers in Iran-2

Podoces, 2007, 2(2): 77–96 A Century of Breeding Bird Assessment by Western Travellers in Iran, 1876–1977 1 1,2 C. S. (KEES) ROSELAAR * & MANSOUR ALIABADIAN 1. Zoological Museum & Institute of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Dynamics, University of Amsterdam PO Box 94766, 1090 GT Amsterdam, the Netherlands 2. Faculty of Science, Department of Biology, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran * Correspondence Author. Email: [email protected] Received 14 June 2007; accepted 1 December 2007 Abstract: This article lists 99 articles on distribution of wild birds in Iran, which appeared between 1876 and 1977 and which were published by authors writing in European languages. Each paper has a reference number and is supplied with annotations, giving the localities and time of year where the bird observations had been made. These localities are also listed on a separate website (www.wesca.net/podoces/podoces.html), supplied with coordinates and the reference number. With help of these coordinates and the original publications an historical atlas of bird distribution in Iran can be made. A few preliminary examples of such maps are included. Many authors also collected bird specimens in Iran, either to support their identifications or in order to enravel subspecies taxonomy of the birds of Iran. The more important natural history museums containing study specimens from Iran are listed. Keywords: Iran, Zarudnyi, Koelz, birds, gazetteer, literature, Passer, Podoces, Sitta . ﻣﻘﺎﻟﻪ ﺣﺎﺿﺮ ﺑﻪ ﺷﺮﺡ ﻣﺨﺘﺼﺮﻱ ﺍﺯ ﻣﻜﺎ ﻥﻫﺎ ﻭ ﺯﻣﺎ ﻥ ﻫﺎﻱ ﻣﺸﺎﻫﺪﻩ ﭘﺮﻧﺪﮔﺎﻥ ﺍﻳﺮﺍﻥ ﺑﺮ ﺍﺳﺎﺱ ۹۹ ﻣﻘﺎﻟﻪ ﺍﺯ ﭘﺮﻧﺪﻩﺷﻨﺎﺳـﺎﻥ ﺍﺭﻭﭘـﺎﻳﻲ ﺩﺭ ﺑـﻴﻦ ﺳـــﺎﻝ ﻫـــﺎﻱ ۱۸۷۶ ﺗـــﺎ ۱۹۷۷ ﻣـــﻲ ﭘـــﺮﺩﺍﺯﺩ ﻛـــﻪﻣﺨﺘـــﺼﺎﺕ ﺟﻐﺮﺍﻓﻴـــﺎﻳﻲ ﺍﻳـــﻦ ﻣﻜـــﺎ ﻥﻫـــﺎ ﻗﺎﺑـــﻞ ﺩﺳﺘﺮﺳـــﻲ ﺩﺭ ﺁﺩﺭﺱ www.wesca.net/podoces/podoces.html ﻣ ﻲ ﺑﺎﺷﺪ . -

Epidemiological Survey on Scorpionism in Gotvand County

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Journal of Acute Disease (2014)314-319 314 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Acute Disease journal homepage: www.jadweb.org Document heading doi: 10.1016/S2221-6189(14)60067-6 Epidemiological survey on scorpionism in Gotvand County, Southwestern Iran: an analysis of 1 067 patients Hamid Kassiri1*, Elnaz Kassiri2, Rahele Veys-Behbahani1, Ali Kassiri3 1Health School, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran 2Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran 3Medicine School, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Objective: To study epidemiologic parameters of scorpion stings in Gotvand County, Received 8 August 2013 Methods: Southwestern Iran, during 2006-2008. In this descriptive study, data were collected Received in revised form 15 September 2013 G C A Accepted 24 September 2013 from health services center's files at otvand ounty. special scorpion sting sheet was T Available online 20 November 2014 prepared. his sheet contained information about the site of scorpion stung, the date and place of the accident, the sex of the injured and etc. TheResults: frequencies of entomo-epidemiological Keywords: characters were changed to the percentage basis. Cases were collected from health Scorpion sting services center's files over three years. There were 1 067 scorpion victims, 44.1% of whom were Epidemiology from rural areas. Stings occurred throughout the year, however, the highest and lowest frequency Incidence rate happened in August (12.5%), January (1.9%) and February (1.9%), respectively. -

Irak and Neighbour Countries

FICSS in DOS Iraq and neighbouring countries Field Information and Coordination Support Section Division of Operational Services As of April 2007 (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( Jebrail (((( (((( (((( Akbenli (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( Shahbuz (((( Kaman(((( (((( Çilbah (((( (((( (((( Divrigi (((( (((( (((( (((( R (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( Hinis (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( Sarkisla (((( Deliktas Gubadly Neftchala Karacaoren (((( (((( (((( 33°E 34°E 35°E 36°E (((( 37°E 38°E 39°E 40°E 41°E 42°E 43°E 44°E 45°E 46°E 47°E 48°E 49°E 50°E 51°E 52°E 53°E (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( O (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( Caylar (((( (((( ((Uzunlu(( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( Kangal Karaoglan (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( Nakhchivan (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( Jalilabad (((( (((( (((( W (((( (((( (((( Varto (((( ¿¿ (((( (((( (((( (((( ¿ (((( (( ¿ (( ¿ (((( (((( ¿ (((( . ((( ¿ ( ¿ Seker (((( (((( ¿ (((( (((( ¿ (((( ¿ ((( ¿ ( ¿ (((( Kirsehir ¿ Kadzharan (((( ¿ (((( ¿ ( ¿ ((( ¿ (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( Akpinar(((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( Hozat(((( Tunceli (((( (((( (((( (((( Goytepe (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( Sancak Bulanik Paraga (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( Zangilan C (((( (((( (((( Horan (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( Arapkir (((( Ercis (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( Masally L (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( 39° N (((( (((( (((( (((( -

A Case of Religious Architecture in Elymais: the Tetrastyle Temple of Bard-E Neshandeh

Annali, Sezione orientale 77 (2017) 134–180 brill.com/aioo A Case of Religious Architecture in Elymais: The Tetrastyle Temple of Bard-e Neshandeh Davide Salaris Macquarie University—Sydney [email protected] Abstract This study provides a new approach and interpretation of a remote Elymaean tetrastyle temple found in the course of excavations conducted at the sacred terraces of Bard-e Neshandeh in the mid-19th century. Perched on the heights of the Zagros mountains in the current province of Khuzestan (SW Iran), the shrine on the lower terrace reflects an innovative synthesis of structural elements engaging both Mesopotamian and Iranian templates and it occupies a special place in the records of temple architecture of the Iranian world before the Sasanid conquest. According to this investigation, a re- evaluation of the tetrastyle temple is proposed in order that it will yield new insights and progress of understanding on the cultic monumental apparatus in Hellenistic and Parthian Elymais.1 Keywords Elymais – Khuzestan – temple architecture – Seleucid-Parthian Iran 1 I would like to express my deep gratitude to my first mentor Prof. Pierfrancesco Callieri. I am extremely thankful and indebted to him for directing me towards the topic of this paper, and sincere guidance and encouragement extended to me over the years. I would also like to express my very great appreciation to Dr. Gian Pietro Basello for his valuable photographic material and constructive suggestions during the development of this research work. His willingness to give his time so generously has been very much appreciated. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, ���7 | doi �0.��63/�468563�-��Downloaded3400�9 from Brill.com10/06/2021 04:52:47PM via free access A Case of Religious Architecture in Elymais 135 1 Introduction General View The reconstruction of history and religious traditions of ancient Iran is deep- ly dependent on philological and epigraphical studies, leaving behind many questions still to be resolved.