Master Plan for Mineral Extraction Douglas County

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CRETACEOUS-TERTIARY BOUNDARY Ijst the ROCKY MOUNTAIN REGION1

BULLETIN OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA V o l..¿5, pp. 325-340 September 15, 1914 PROCEEDINGS OF THE PALEONTOLOGICAL SOCIETY CRETACEOUS-TERTIARY BOUNDARY IjST THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN REGION1 BY P. H . KNOWLTON (Presented before the Paleontological Society December 31, 1913) CONTENTS Page Introduction........................................................................................................... 325 Stratigraphic evidence........................................................................................ 325 Paleobotanical evidence...................................................................................... 331 Diastrophic evidence........................................................................................... 334 The European time scale.................................................................................. 335 Vertebrate evidence............................................................................................ 337 Invertebrate evidence.......................................................................................... 339 Conclusions............................................................................................................ 340 I ntroduction The thesis of this paper is as follows: It is proposed to show that the dinosaur-bearing beds known as “Ceratops beds,” “Lance Creek bieds,” Lance formation, “Hell Creek beds,” “Somber beds,” “Lower Fort Union,”- Laramie of many writers, “Upper Laramie,” Arapahoe, Denver, Dawson, and their equivalents, are above a major -

Analysis and Correlation of Growth

ANALYSIS AND CORRELATION OF GROWTH STRATA OF THE CRETACEOUS TO PALEOCENE LOWER DAWSON FORMATION: INSIGHT INTO THE TECTONO-STRATIGRAPHIC EVOLUTION OF THE COLORADO FRONT RANGE by Korey Tae Harvey A thesis submitted to the Faculty and Board of Trustees of the Colorado School of Mines in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science (Geology). Golden, Colorado Date __________________________ Signed: ________________________ Korey Harvey Signed: ________________________ Dr. Jennifer Aschoff Thesis Advisor Golden, Colorado Date ___________________________ Signed: _________________________ Dr. Paul Santi Professor and Head Department of Geology and Geological Engineering ii ABSTRACT Despite numerous studies of Laramide-style (i.e., basement-cored) structures, their 4-dimensional structural evolution and relationship to adjacent sedimentary basins are not well understood. Analysis and correlation of growth strata along the eastern Colorado Front Range (CFR) help decipher the along-strike linkage of thrust structures and their affect on sediment dispersal. Growth strata, and the syntectonic unconformities within them, record the relative roles of uplift and deposition through time; when mapped along-strike, they provide insight into the location and geometry of structures through time. This paper presents an integrated structural- stratigraphic analysis and correlation of three growth-strata assemblages within the fluvial and fluvial megafan deposits of the lowermost Cretaceous to Paleocene Dawson Formation on the eastern CFR between Colorado Springs, CO and Sedalia, CO. Structural attitudes from 12 stratigraphic profiles at the three locales record dip discordances that highlight syntectonic unconformities within the growth strata packages. Eight traditional-type syntectonic unconformities were correlated along-strike of the eastern CFR distinguish six phases of uplift in the central portion of the CFR. -

Geologic Studies of the Platte River, South-Central Nebraska and Adjacent Areas—Geologic Maps, Subsurface Study, and Geologic History

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Publications of the US Geological Survey US Geological Survey 2005 Geologic Studies of the Platte River, South-Central Nebraska and Adjacent Areas—Geologic Maps, Subsurface Study, and Geologic History Steven M. Condon Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgspubs Part of the Earth Sciences Commons Condon, Steven M., "Geologic Studies of the Platte River, South-Central Nebraska and Adjacent Areas—Geologic Maps, Subsurface Study, and Geologic History" (2005). Publications of the US Geological Survey. 22. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgspubs/22 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the US Geological Survey at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications of the US Geological Survey by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Geologic Studies of the Platte River, South- Central Nebraska and Adjacent Areas—Geologic Maps, Subsurface Study, and Geologic History Professional Paper 1706 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Geologic Studies of the Platte River, South-Central Nebraska and Adjacent Areas—Geologic Maps, Subsurface Study, and Geologic History By Steven M. Condon Professional Paper 1706 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior Gale A. Norton, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Charles G. Groat, Director Version 1.0, 2005 This publication and any updates to it are available online at: http://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/pp1706/ Manuscript approved for publication, March 3, 2005 Text edited by James W. Hendley II Layout and design by Stephen L. -

Geologic Characterization 111 Date 7/31/91 List of Appendices

Characterization GEOLOGIC Prepared by ? TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION ....................................... 1 1.1 Purpose ........................................... 1 1.2 Scope of Characterization .............................. 1 1.2.1 Literature Search .... ........................... 1 1.2.2 Core Processing and Description ..................... 2 1.2.3 Reprocessing of Seismic Data ........................ 2 1.2.4 Grain Size Analysis .............................. 2 1.2.5 Geologic Report ................................ 3 1.3 Location and General Setting ...., ........................ 3 1.4 Previous Studies ...................................... 5 2.0 STRATIGRAPHY ....................................... 7 Precambrian ......................................... 2.1 7 2.2 Paleozoic And Mesozoic Sedimentary Section ................ 2.2.1 Fountain Formation (PennsylvanianPermian) ............ 7 2.2.2 Lyons Sandstone Formation (Permian) ................ 7 2.2.3 Lykins Formation (PermianrTriassic) ................. 10 2.2.4 Ralston Creek Formation (Jiurassic) .................. 10 2.2.5 Momson Formation (Jurassic) ...................... 10 2.2.6 Dakota Group (Lower Cretaceous) ................... 10 2.2.7 Benton Shale Formation (Lower/Upper Cretaceous) ....... 11 2.2.8 Niobrara Formation (Upper Cretaceous) ............... 11 2.2.9 Pierre Shale Formation (Upper Cretaceous) ............. 11 2.2.10 Fox Hills Sandstone Formation (Upper Cretaceous) ....... 12 2.2.1 1 Laramie Formation (Upper Cretaceous) ............... 12 2.2.12 -

Improvement of the Geotechnical Axial Design Methodology for Colorado’S Drilled Shafts Socketed in Weak Rocks

Report No. CDOT-DTD-R-2003-6 Final Report IMPROVEMENT OF THE GEOTECHNICAL AXIAL DESIGN METHODOLOGY FOR COLORADO’S DRILLED SHAFTS SOCKETED IN WEAK ROCKS Naser Abu-Hejleh Michael W. O'Neill Dennis Hanneman William J. Atwooll July 2003 COLORADO DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BRANCH The contents of this report reflect the views of the author(s), who is(are) responsible for the facts and accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Colorado Department of Transportation or the Federal Highway Administration. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. The preliminary design recommendations should be considered for only conditions very close to those encountered at the load test sites and per the qualifications described in Chapter 6. Use of the information contained in the report is at the sole discretion of the designer. i Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. CDOT-DTD-R-2003-6 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date July 2003 IMPROVEMENT OF THE GEOTECHNICAL AXIAL DESIGN METHODOLOGY FOR COLORADO’S DRILLED SHAFTS SOCKETED 6. Performing Organization Code IN WEAK ROCKS 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. CDOT-DTD-R-2003-6 Naser Abu-Hejleh, Michael W. O'Neill, Dennis Hanneman, William J. Atwooll 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Colorado Department of Transportation 11. Contract or Grant No. 4201 E. Arkansas Ave Performed internally by CDOT-Research Office Denver, Colorado 80222 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. -

Diachronous Development of Great Unconformities Before Neoproterozoic Snowball Earth

Diachronous development of Great Unconformities before Neoproterozoic Snowball Earth Rebecca M. Flowersa,1, Francis A. Macdonaldb, Christine S. Siddowayc, and Rachel Havraneka aDepartment of Geological Sciences, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309; bEarth Science Department, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106; and cDepartment of Geology, The Colorado College, Colorado Springs, CO 80903 Edited by Paul F. Hoffman, University of Victoria, Victoria, Canada, and approved March 6, 2020 (received for review July 30, 2019) The Great Unconformity marks a major gap in the continental precisely because the Great Unconformities mark a large gap in geological record, separating Precambrian basement from Phan- the rock record, the erosion history leading to their formation erozoic sedimentary rocks. However, the timing, magnitude, cannot be investigated directly by study of preserved units. spatial heterogeneity, and causes of the erosional event(s) and/ Past work leads to at least four general models for the timing or depositional hiatus that lead to its development are unknown. and magnitude of pre-Great Unconformity continental erosion, We present field relationships from the 1.07-Ga Pikes Peak batho- which are depicted in Fig. 1. Some have proposed major erosion lith in Colorado that constrain the position of Cryogenian and of the continents associated with assembly of the supercontinent Cambrian paleosurfaces below the Great Unconformity. Tavakaiv Rodinia and mantle upwelling below it prior to 850 Ma (Hy- sandstone injectites with an age of ≥676 ± 26 Ma cut Pikes Peak pothesis 1) or with the early diachronous breakup of Rodinia granite. Injection of quartzose sediment in bulbous bodies indi- between 850 and 717 Ma (Hypothesis 2) (10–17). -

![Italic Page Numbers Indicate Major References]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6112/italic-page-numbers-indicate-major-references-2466112.webp)

Italic Page Numbers Indicate Major References]

Index [Italic page numbers indicate major references] Abbott Formation, 411 379 Bear River Formation, 163 Abo Formation, 281, 282, 286, 302 seismicity, 22 Bear Springs Formation, 315 Absaroka Mountains, 111 Appalachian Orogen, 5, 9, 13, 28 Bearpaw cyclothem, 80 Absaroka sequence, 37, 44, 50, 186, Appalachian Plateau, 9, 427 Bearpaw Mountains, 111 191,233,251, 275, 377, 378, Appalachian Province, 28 Beartooth Mountains, 201, 203 383, 409 Appalachian Ridge, 427 Beartooth shelf, 92, 94 Absaroka thrust fault, 158, 159 Appalachian Shelf, 32 Beartooth uplift, 92, 110, 114 Acadian orogen, 403, 452 Appalachian Trough, 460 Beaver Creek thrust fault, 157 Adaville Formation, 164 Appalachian Valley, 427 Beaver Island, 366 Adirondack Mountains, 6, 433 Araby Formation, 435 Beaverhead Group, 101, 104 Admire Group, 325 Arapahoe Formation, 189 Bedford Shale, 376 Agate Creek fault, 123, 182 Arapien Shale, 71, 73, 74 Beekmantown Group, 440, 445 Alabama, 36, 427,471 Arbuckle anticline, 327, 329, 331 Belden Shale, 57, 123, 127 Alacran Mountain Formation, 283 Arbuckle Group, 186, 269 Bell Canyon Formation, 287 Alamosa Formation, 169, 170 Arbuckle Mountains, 309, 310, 312, Bell Creek oil field, Montana, 81 Alaska Bench Limestone, 93 328 Bell Ranch Formation, 72, 73 Alberta shelf, 92, 94 Arbuckle Uplift, 11, 37, 318, 324 Bell Shale, 375 Albion-Scioio oil field, Michigan, Archean rocks, 5, 49, 225 Belle Fourche River, 207 373 Archeolithoporella, 283 Belt Island complex, 97, 98 Albuquerque Basin, 111, 165, 167, Ardmore Basin, 11, 37, 307, 308, Belt Supergroup, 28, 53 168, 169 309, 317, 318, 326, 347 Bend Arch, 262, 275, 277, 290, 346, Algonquin Arch, 361 Arikaree Formation, 165, 190 347 Alibates Bed, 326 Arizona, 19, 43, 44, S3, 67. -

Western Interior Seaway

() . Paleogeo.graphy of the Late Cretaceous of the Western Interior otMfddle North America+ j?'oal .Blstribution anct,Sedimen~cumulation By Laura N. Robinson Roberts and Mark A. Kirschbaum U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1561 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1995 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Gordon P. Eaton, Director For sale by U.S. Geological Survey, Information Services Box 25286, Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 Any use of trade, product, or finn names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Roberts, Laura N. Robinson. Paleogeography of the Late Cretaceous of the western interior of middle North America : coal distribution and sediment accumulation I by Laura N. Robinson Roberts and Mark A. Kirschbaum. p. em.- (U.S. Geological Survey professional paper ; 1561) Includes bibliographical references. Supt. of Docs. no.: I 19.16: 1561 1. Paleogeography-Cretaceous. 2. Paleogeography-West (U.S.). 3. Coal Geology-West (U.S.). I. Kirschbaum, Mark A. II. Title. III. Series. QE50 1.4.P3R63 1995 553.2'1'0978-dc20 94-39032 CIP CONTENTS Abstract........................................................................................................................... 1" Introduction ................................................................................................................... Western Interior Seaway ... .. ... ... ... .. .. .. -

Oil and Gas Exploration and Development Along the Front Range in the Denver Basin of Colorado, Nebraska, and Wyoming by Debra K

Chapter 2 Oil and Gas Exploration and Development along the Front Range in the Denver Basin of Colorado, Nebraska, and Wyoming By Debra K. Higley and Dave O. Cox Chapter 2 of Petroleum Systems and Assessment of Undiscovered Oil and Gas in the Denver Basin Province, Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Wyoming—USGS Province 39 Compiled by Debra K. Higley U.S. Geological Survey Digital Data Series DDS–69–P U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark D. Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2007 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1–888–ASK–USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone:1–888–ASK–USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Higley, D.K., Cox, D.O., 2007, Oil and gas exploration and development along the front range in the Denver Basin of Colorado, Nebraska, and Wyoming, in Higley, D.K., compiler, Petroleum systems and assessment of undiscovered oil and gas in the Denver Basin Province, Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Wyoming—USGS Province 39: U.S. -

PALYNOLOGY of the UPPERMOST LARAMIE and ARAPAHOE FOI&Lations at ‘TEE ROCKY FLATS PLANT Mar GOLDEN, COLORADO

,,- - - -,- FINAL REPORT PALYNOLOGY OF THE UPPERMOST LARAMIE AND ARAPAHOE FOI&lATIONS AT ‘TEE ROCKY FLATS PLANT mAR GOLDEN, COLORADO U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY Rocky Flats hant Golden, Colorado ENVIRONMENTAL RESTORATION PROGRAM 30 APRIL 1993 Text, Table, and Plates mMIN RECORD S W-A-004907 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section -Title Page 1.o STUDY OBJECTIVES 1 2.0 INTRODUCTION 3 3.0 METHODS 4 4.0 RESULTS 5 5.0 CONCLUSIONS 10 6.0 REFERENCES CITED 11 Palynology of the Uppermost Laramie Final Report and Arapahoe Formations at the April 30, 1993 Rocky Flab Plant oc81 OOkh Colorado i LIST OF TABLES Number -Title 1 ROCKY FLATS POLLEN, SPORES, AND DINOFLAGELLATE OCCURRENCES IN WELLS #B217489, #B218589, #00291, #00191, AND #B3 15289 2 ROCKY FLATS POLLEN, SPORES, AND DINOFLAGELLATE OCCURRENCES IN WELLS M2892, #40891, #40591, #40591, #B217689, AND #B217789 3 A COMPOSITE OF ROCKY FLATS POLLEN, SPORES, AND DINOFLAGELLATE OCCURRENCES IN WELLS #B217489 AND #B218589 Palyaology of tbc Uppamost Laramie and Arapabw Fommtiona at the 3 Rocky fiats Plant m?ar Go- Colorado ii PALYNOLOGY PLATES -Title Plate Nos. NON-MARINE FORMS: FERN SPORES 1-14 GYMNOSPERM POLLEN 15 - 20 ANGIOSPERM POLLEN 21 - 38 MARINE FORMS: DINOFLAGELLATES 39 - 44 I Palywlogy of the Uppamost Laramae FiReport andAra&oe Formatiom at tbe Apnl30.1993 Rocky nats Plant near Go- Colorado iii LIST OF APPENDICES Number -Title 1 TWO MEMOS FROM FRED GRIGSBY RE: POTENTIAL SUBSURFACE STRATIGRAPHIC MARKER BEDS 2 LrrHOLOGIC WELL LOGS 3 PLANT MICROFOSSIL COUNT DATA FROM WELL a17489 AND WELL W291 Palynology of the Uppermost Laramie FiiReport andArapaboeFomratiOllsattbe April 30.1993 5 Rocky Flats Plant near Goldea Colorado iv 1.0 STUDY OBJECTIVES The current geologic characterization model for the Rocky Flats Plant (RFP) establishes au environment of deposition that is based upon interpretation of stratigraphic data obtained from numerous boreholes and wells installed throughout the plant Site. -

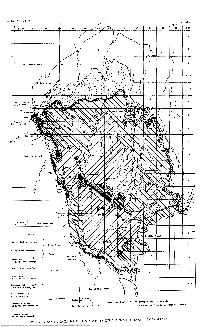

Laramie Correlation Map of the Denver

11. Geol. Soc. Am., vol. 67 Reichert R.5I Legend Castle Rock conglomerate l-\ Castle Rock volcanics ~" • Oawton arkose (re-defined and extended) Table Mountain basalt flows Denver formation (re-defined and extended) Cretaceous - Poleocene contact—-/ of R.W.Brown(l943,p.67) Sasal member of Denver formation Base mop drawn from 1935 geological map of Colorado Arapahoe formation (re-defined and extended) Note: Compare with Plate 2 Correlolion by Stanley 0. Reichert 1955 .oramle formation as originally defined) -LARAMIE CORRELATION MAP OF THE DENVER BASIN, COLORADO POST Downloaded from http://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/gsa/gsabulletin/article-pdf/67/1/107/3441540/i0016-7606-67-1-107.pdf by guest on 02 October 2021 BULLETIN OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA VOL. 67. PP. 107-112, 2 PLS. JANUARY 1956 POST-LARAMIE STRATIGRAPHIC CORRELATIONS IN THE DENVER BASIN, COLORADO BY STANLEY O. REICHERT ABSTRACT In mapping and correlating post-Laramie formations in the Denver Basin, clear-cut mappable formation boundaries have been defined and used. It is proposed that (1) the Laramie-Arapahoe contact remain as originally defined by Emmons, Cross, andEldridge (1896); (2) the Arapahoe-Denver contact be placed at the widespread erosional disconformity at the base of the lowest, thickest, and most prominent basalt-andesite pebble conglom- erate bed in the Denver area, instead of at the first appearance of andesitic debris as originally proposed by Emmons, Cross, and Eldridge (1896). The following changes in nomenclature are proposed: (1) The Arapahoe and Denver formations can be mapped throughout the Denver Basin, and these names should replace the term "lower Dawson" of Dane and Pierce (1936). -

The Contact of the Fox Hills and Lance Formations

Please do not destroy or throw away this publication. If you have no furtlier use for it, write to the Geological Survey at Washington and ask for a frank t» return it DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Ray Lyman Wilbur, Secretary XI. S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY RECEIVED George Otis Smith, Director UtC 1 0 192931 Professional Paper 158—B L. C. DfcCIUS THE CONTACT OF THE FOX HILLS AND LANCE FORMATIONS BY C. E. DOBBIN AND JOHN B. REESIDE, JR. Shorter contributions to general geology, 1929 (Pages 9-25) UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1929 CONTENTS Pagfr Abstract. _______________________________________________________________________________________________ 9 Introduction. _______________________________________________________________________________________________ 9 Questions involved and general conclusions _______________________________________________________ _^_ _____________ 9 Criteria for separation of the Fox Hills and Lance formations__-_____-_-_-_-__---_--____-__________________________ 11 Fox Hills and Lance formations in different regions_-_____-_____--__---__-___--_______-_________________________ 11 Mouth of Cannonball Eiver, N. Dak______-_______-____________-___-_---___--_-_-_-_____-__-_______________ 11 Cannonball River to Fox Ridge, S. Dak____________________________________________________________________ 12 Fox Ridge to Little Missouri River, S. Dak__________________________________________________________________ 14 Marmarth, N. Dak________________________________________________________________________________________