Parental Attitudes and School Choice: the Public/Private Distinction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Football Program 2020

FOOTBALL PROGRAM 2020 20 19 92nd SEASON OF Wesgroup is a proud supporter of Vancouver College’s Fighting Irish Football Team. FOOTBALL 5400 Cartier Street, Vancouver BC V6M 3A5 TABLE OF CONTENTS Principal’s Message ...............................................................2 Irish Football Team Awards 1941-2019 ..............................19 Head Coach’s Message .........................................................2 Irish Records 1986-2019 ......................................................22 Vancouver College Staff and Schedules 2020 .......................3 Irish Provincial Championship Game 2020 Fighting Irish Coaches and Supporting Staff ................4 Award Winners 1966-2018 .................................................29 Irish Alumni Currently Playing in the CFL and NFL ................5 Back in the Day ....................................................................29 2020 Fighting Irish Graduating Seniors .................................6 Irish Cumulative Record Against Opponents 1929-2018 .....30 Fighting Irish Varsity Statistical Leaders 2019 ......................8 Fighting Irish Varsity Football Team 2019 ...........................34 Vancouver College Football Awards 2019 .............................9 Irish Statistics 1996-2018 ...................................................35 Irish Varsity Football Academic Awards ...............................10 Archbishops’ Trophy Series 1957-2018 .............................38 Irish Academics 2020 ..........................................................10 -

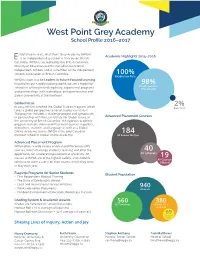

West Point Grey Academy School Profile 2016–2017

West Point Grey Academy School Profile 2016–2017 stablished in 1996, West Point Grey Academy (WPGA) Academic Highlights 2015–2016 E is an independent day school in Vancouver, British Columbia. WPGA is accredited by the British Columbia Ministry of Education and the Canadian Accredited Independent Schools and is a member of the Independent Schools Association of British Columbia. raduation Rate WPGA’s vision is to be Leaders in Future-Focused Learning. Inspired by our rapidly evolving world, we are a model for ostsecondary schools in offering interdisciplinary, experiential programs lacements and partnerships, with technology, entrepreneurship and global connectivity at the forefront. Global Focus In 2014, WPGA launched the Global Studies Program, which ap ear takes a global perspective to social studies curriculum. The program includes a challenge project and symposium in partnership with the Liu Institute for Global Issues at Advanced Placement Courses the University of British Columbia; the rigorous academic program includes Advanced Placement courses in politics, economics, statistics and language as well as a Global Online Academy course (WPGA is the only Canadian 184 member school in Global Online Academy). A ams ritten Advanced Placement Program WPGA offers a wide variety of Advanced Placement (AP) courses, which challenge students’ learning and offer the 40 opportunity for accelerated placement at university. AP A Scholars classes at WPGA are of the highest calibre, and students continue to score a 4 or 5 on their exams, which they write in May each year. Flagship Programs for Senior Students Student Population • First Responders Medical Training • The Duke of Edinburgh’s Award • Local and International Service Initiatives • Work Experience Placements Students • Outdoor Environmental Education; Wilderness Pursuits Grading System & Academic Awards 560 380 Grades are reflected on school transcripts. -

Download/Technology/Digital%20Natives%20

Cycling 11 as a Step to Align Learning in Secondary Schools with Learning in the ‘Real World’ by Darryl Dietrich A GRADUATING PAPER SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULLFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Education in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Curriculum and Pedagogy) The University of British Columbia ©Darryl Dietrich June 26, 2013 Acknowledgement My graduate advisor and project supervisor, Dr. Marina Milner-Bolotin, has provided guidance and support in the completion of this paper. I am extremely thankful for the time she has committed and the advice she has provided to help keep this project on track. I would also like to thank the Magee Secondary School community, namely colleagues and administrators for the assistance and support for bringing Cycling 11 to fruition as a locally developed course to run in Vancouver secondary schools. Lastly, and most importantly, thank you to my partner, Allison, who has been so very supportive over the duration of this Master’s program. The wisdom, advice, and support of many are very much appreciated. 2 Abstract “If we want young people with the competencies to innovate and make our economy more competitive, we need to model our schools after how innovation actually happens”1 ~Dr. Pasi Sahlberg (Finnish educator, scholar, and policy advisor) As I see it, the educational landscape in British Columbia, Canada is contradictory in its present state. Our education system, from the Ministry of Education at the top, down to teachers and students in classrooms, are not preparing students for success in the post-secondary world. There is a disconnect between how people learn after secondary school with how we expect them to learn while enrolled in school. -

Differences in Experiences, Aspirations and Life Chances Between East Side and West Side Vancouver Secondary Graduates at Mid-Century: an Oral History

Differences in Experiences, Aspirations and Life Chances between East Side and West Side Vancouver Secondary Graduates at Mid-Century: an Oral History by Janet Mary Nicol B.A., The University of British Columbia, 1979 Teacher's Certificate, University of British Columbia, 1986 A THESIS IN PARTIAL FUIJILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES THE FACULTY OF EDUCATION Department of Educational Studies ~ We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA July 15, 1996 © Janet Mary Nicol, 1996 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada DE-6 (2/88) -11- ABSTRACT A history of growing up in Vancouver in the 1950s was constructed by interviewing eight former students of Vancouver Technical Secondary School in a working class neighborhood on the city's east side, and eight from Magee Secondary School in a middle class neighborhood on the west side. All 16 graduated from grade 12 in 1955. They responded to a general mailing obtained from reunion address lists. In their interviews, they discussed both their lives as adolescents and their life paths since graduation. -

Curriculum Vitae RONALD W. MARX

Curriculum Vitae RONALD W. MARX CONTACT INFORMATION Office College of Education University of Arizona 1430 E. 2nd Street PO Box 210069 Tucson, AZ 85721-0069 (520) 621-9640 (office) (520) 205-0404 (mobile) DEGREES Stanford University 1978 Ph.D, Educational Psychology and Child Development California State University, Northridge 1971 M.A., School Psychology California State University, Northridge 1969 B.A. (cum laude), Psychology CERTIFICATION State of California Life Credential, Pupil Personnel Services: School Psychology Community College Teaching Credential: Psychology Province of British Columbia Licensed Psychologist (lapsed) -2- 2 PROFESSIONAL EMPLOYMENT 2017- Professor of Educational Psychology Dean Emeritus University of Arizona 2003-2017 Dean Professor of Educational Psychology Paul L. Lindsey and Kathy J. Alexander Chair in Education University of Arizona 1990-2003 Professor, Educational Studies Program, School of Education University of Michigan 1984-1990 Professor 1983-1987 Director of Graduate Programs 1979-1988 Senior Researcher, Instructional Psychology Research Group 1979-1984 Associate Professor 1975-1979 Assistant Professor Faculty of Education, Simon Fraser University Burnaby, British Columbia 1987-1988 Director of Research Learner's Group, British Columbia Royal Commission on Education 1982-1983 Visiting Scholar Department of Educational Psychology, University of Arizona 1977, 1979 , 1980, 1981 (Summers) Visiting Member Department of Educational Psychology, Faculty of Education University of British Columbia 1975 Teaching -

2017 Special General Minutes & Appendices

Sydney Landing, 2003A-3713 Kensington Ave, Burnaby, BC V5B 0A7 Phone: 604-477-1488|[email protected]|www.bcschoolsports.ca BC School Sports Minutes (Draft) SPECIAL GENERAL MEETING Tuesday, December 12, 2017 BC School Sports Office 2003A – 3713 Kensington Ave., Burnaby, BC BC SCHOOL SPORTS SPECIAL GENERAL MEETING Tuesday, December 12, 2017 BC School Sports 2003A-3713 Kensington Avenue, Burnaby, BC 1. Call to order – Mike Allina 1.1. Welcome and Opening Remarks At 7:16 pm Mike Allina, President, welcomed all delegates to the Special General Meeting. He thanked delegates for attending and for their commitment to high school sports. 2. Meeting Information and Announcements – Mike Allina 2.1. Notice of Meeting The notice of meeting was sent to all the members of the Society on November 21, 2017, and the minimum requirement of 14 days’ notice has been complied with. 2.2. Quorum • The quorum is 50 members in good standing, or 20% of the members in good standing whichever is greater. We have 440 member schools so 20% is 88 members. Our quorum also requires that we have at least one vote from each of the designated zones. As well, votes cast in person, by proxy or in advance will count towards quorum. • Geographic regions set out in Schedule B of the bylaws may be amended from time to time by Ordinary Resolution. • An Ordinary Resolution is passed by a simple majority of the votes cast at a General Meeting. • As of 7:15 pm, we have 159 members in good standing present in person, by proxy, or whom has cast an Advanced Vote, and all zones represented, therefore this meeting is duly convened. -

2019 BCSS AGM Package 2!.Pdf

April 26th - 27th, 2019 BCWhistler, SCHOOL British Columbia SPORTS Annual General Meeting Kelowna, British Columbia MEETING PACKAGE 2 April 2019 The Cove Lakeside Resort Kelowna, BC General Information The Cove Lakeside Resort - West Kelowna Hotel Information The Cove Lakeside Resort is located on the western shore of Okanagan Lake. The Resort features elegantly decorated rooms, stunning views and comfortable in-room amenities. If you have booked a room through BCSS, you will have received a confi rmation email from Karen Hum, please check to make sure the reservation information is correct. Things to do in Kelowna • Visit a Winery - Quail’s Gate Winery & Mission Hill Family Estate Winery are a short distance to from the hotel • Visit Bear Creek Provincial Park - A beautiful Provincial Park on the west side of Okanagan Lake • Relax at Lake Okanagan - Can you spot the Ogopogo? • Enjoy a Round of Golf - Test your skills at one of Kelowna’s 19 exceptional courses • Shopping - Kelowna’s downtown shopping core has a blend of retail shops, galleries, and boutiques to explore. Transportation The Cove Lakeside Resort is located at: 4205 Gellatly Road West Kelowna, BC V4T 2K2 Airport Kelowna International Airport has frequent fl ights in and out daily from around the province. It is a short trip from the Airport to the Resort. If you will be fl ying in to the AGM please let us know and we can help with arrangements for transportation to the hotel. Distance to and from the airport is 29km and approximately 25-40 minutes. Kelowna Weather Kelowna’s weather this time of year ranges from: Average Daily High: 15°C Average Daily Low: 3°C Please keep an eye on the weather closer to the AGM, and pack accordingly. -

Post-Secondary Planning Guide 2020-2021 Changing Destiny by Changing Minds Contents

POST-SECONDARY PLANNING GUIDE 2020-2021 CHANGING DESTINY BY CHANGING MINDS CONTENTS About this Guidebook 02 Graduation Requirements 03 What is the Career Life Connections Program? 04 Current University and College Operations Amid COVID-19 06 Application and Admission Procedures Summary 2020-21 08 Accessibility Services at Post-Secondary Institutions 10 Psychological-Educational Assessments and Post-Secondary Education 11 Self-Advocacy 12 Post-Secondary Checklist for Students with Learning Differences 13 Post-Secondary Education Institutions 14 Volunteer and Travel Programs 22 General Information on Scholarships, Awards, and Financial Aid 24 Canadian Bursaries for Students with Disabilities 26 © Fraser Academy ABOUT THIS GUIDEBOOK This booklet contains important information for your son or daughter’s final year at Fraser Academy. All information is accurate as of September 2020. For those students wanting to attend post-secondary institutions, the program options are practically limitless. As each student has unique needs, preferences and circumstances, finding a good fit is the result of teamwork (student, plus his or her family, teachers and counsellors). Each institution has its own application opening and deadline dates, as well as documentation requirements. Check each individual school online for the most up-to-date information. Please note that admission averages are re-calculated every year, which is often based on the applicant pool for that year. There are also many options for those students taking a year off, including volunteering, working or travelling in Canada or another country. The Post-Secondary Planning Team can help students work on their resume or interviewing skills, and offer information about GAP and other programs. -

ISEA Championships Results

ISEA BC May 22, 2018 OFFICIAL MEET REPORT printed: 2018-05-22 8:27 PM RESULTS #6 Girls 60 Meters (4th Grade A) Pl Name Team Time Note H(Pl) Pts 1 JIANG, Selina Southridge School 9.71 (NW) 2(1) 10 2 WANG, Ann West Point Grey Academy 9.77 (NW) 1(1) 8 3 JEKUBIK, Emily York House School 9.86 (NW) 1(2) 6 4 WAN, Chloe Stratford Hall School 10.33 (NW) 2(2) 5 5 WESTERINGH, Eva Southpointe Academy 10.34 (NW) 2(3) 4 6 MCDONALD, Kate Crofton House School 10.38 (NW) 1(3) 3 7 ALEKSON, Lauren BPS 10.63 (NW) 2(4) 2 8 LINTS, Emily St. John's School 10.88 (NW) 1(4) 1 9 COHEN, Joelle Collingwood School 11.14 (NW) 1(5) 10 ZHOU, Jasmine Meadowridge School 11.59 (NW) 2(5) 11 SHU, Sophie Urban Academy Lions 13.10 (NW) 2(6) SECTION RESULTS Pl Name Team Time Note Section 1 of 2 Wind: (NW) 1 WANG, Ann West Point Grey Academy 9.77 2 JEKUBIK, Emily York House School 9.86 3 MCDONALD, Kate Crofton House School 10.38 4 LINTS, Emily St. John's School 10.88 5 COHEN, Joelle Collingwood School 11.14 Section 2 of 2 Wind: (NW) 1 JIANG, Selina Southridge School 9.71 2 WAN, Chloe Stratford Hall School 10.33 3 WESTERINGH, Eva Southpointe Academy 10.34 4 ALEKSON, Lauren BPS 10.63 5 ZHOU, Jasmine Meadowridge School 11.59 6 SHU, Sophie Urban Academy Lions 13.10 #7 Girls 60 Meters (4th Grade B) Pl Name Team Time Note H(Pl) Pts 1 MILAU, Rachel West Point Grey Academy 9.33 (NW) 2(1) 10 2 HU, Elgina Southridge School 10.02 (NW) 1(1) 8 3 CHAN, Olivia Crofton House School 10.38 (NW) 2(2) 6 4 STEWART, Campbell BPS 10.57 (NW) 1(2) 5 5 SOON, Makaella Stratford Hall School 10.64 (NW) 1(3) 4 6 HERAS , Emma Southpointe Academy 10.71 (NW) 1(4) 3 7 GORDON, Grace York House School 10.76 (NW) 2(3) 2 8 HUTCHINSON, Cecilia Meadowridge School 10.82 (NW) 2(4) 1 9 HUANG, Eva St. -

Head of School Opportunity

HEAD OF SCHOOL OPPORTUNITY WELCOMEWELCOME Founded in 1917, Vancouver Talmud Torah (VTT) is Canada’s largest elementary Jewish day school west of Toronto, serving more than 200 families and 440 students in preschool 3 through grade 7. VTT is an inclusive Jewish day school rooted in Jewish traditions, values and knowledge, and infused with the spirit of chesed and tikkun olam. VTT serves a socially, economically, religiously and academically diverse community through a robust dual-track general and Judaic studies curriculum built upon the principles of 21st century learning. Students are welcomed into a warm, supportive and innovative learning environment, rich with extra-curricular, performing arts, athletic and Jewish values-based programming. MISSION Vancouver Talmud Torah is an inclusive Jewish community day school committed to academic excellence and nurturing lifelong learners who engage the world through Jewish traditions and values. To learn more about VTT’s values, please click here. VISION Families in Greater Vancouver will recognize VTT as the premiere Jewish day school for students from a broad spectrum of Jewish practice and belief. The Jewish community in Vancouver will recognize VTT as a partner in educating Jewish students and an integral part of the fabric of Jewish life in the community. The Greater Vancouver community will recognize the active role VTT plays as a contributor to social justice in the community, across Canada, and around the world. THE OPPORTUNITY VTT presents an exceptional leadership opportunity for the next Head of School. VTT’s next leader will arrive at a particularly exciting time as the school completes the first year of its second century and prepares to appoint its first new HOS in 17 years following the planned retirement of current head, Cathy Lowenstein. -

KITSILANO SECONDARY SCHOOL 2706 Trafalgar Street Vancouver, B.C

KITSILANO SECONDARY SCHOOL 2706 Trafalgar Street Vancouver, B.C. V6K 2J6 Telephone: 604 713-8961 • Fax: 604 713-8960 https://www.vsb.bc.ca/schools/kitsilano May 8, 2020 Dear Kitsilano Families, Thank you for your ongoing support. We continue to be impressed by the strength and resiliency of our school community. Please continue to take care of yourselves and know that we are here to help in any way that we can. If your child or family has any questions or needs support, please do not hesitate to contact us. Information for All Grades Continuity of Learning We are all learning during this pandemic. Learning how to both receive and deliver education. We have heard feedback from our students and families about what is working well and areas for consideration. Please know that teachers and support staff will continue to develop and evolve their approach to the continuity of learning in support of the well-being and success of our students. We continue to encourage all students to engage, to the best of their ability, in the learning opportunities being provided by teachers. We believe that the continuity of learning happening now will add to your foundational knowledge and skills, thereby, leading to success in future courses. Professional Development Day: May 15th Please note that Friday, May 15th is Professional Development Day for all staff. Thus, that day is a non- instructional day and staff will not be available to communicate with students and families. Status of In-Class Instruction Currently, we do not have any detailed information on the status of a return to in-class instruction. -

Ministry of Municipal Affairs Community Gaming Grants PAC/DPAC Sector Recipients 2020-21 Page 1

Ministry of Municipal Affairs Community Gaming Grants PAC/DPAC Sector Recipients 2020-21 DPAC & PAC Community Organization Grant Amount Grant Sector 100 Mile House 100 Mile Elementary School PAC $7,020.00 District Parent Advisory Council and Parent Advisory Council 100 Mile House Peter Skene Ogden Secondary School Parent $10,180.00 District Parent Advisory Council and Parent Advisory Advisory Council Council 108 Mile Ranch Mile 108 Elementary PAC $3,740.00 District Parent Advisory Council and Parent Advisory Council 150 Mile House 150 Mile House Elementary School PAC $3,760.00 District Parent Advisory Council and Parent Advisory Council Abbotsford Abbotsford Senior Secondary School PAC $23,360.00 District Parent Advisory Council and Parent Advisory Council Abbotsford Abbotsford Virtual School PAC $11,900.00 District Parent Advisory Council and Parent Advisory Council Abbotsford Abbotsford Middle School PAC $13,780.00 District Parent Advisory Council and Parent Advisory Council Abbotsford Abbotsford Traditional Middle School PAC $6,560.00 District Parent Advisory Council and Parent Advisory Council Abbotsford Abbotsford Traditional Secondary School PAC $8,320.00 District Parent Advisory Council and Parent Advisory Council Abbotsford Aberdeen Elementary School P.A.C. $4,760.00 District Parent Advisory Council and Parent Advisory Council Abbotsford Auguston Traditional Elementary School PAC $7,320.00 District Parent Advisory Council and Parent Advisory Council Abbotsford Barrowtown Elementary School PAC $1,060.00 District Parent Advisory Council and Parent Advisory Council Abbotsford Blue Jay Elementary PAC $8,700.00 District Parent Advisory Council and Parent Advisory Council Abbotsford Bradner Elementary PAC $2,040.00 District Parent Advisory Council and Parent Advisory Council Abbotsford Centennial Park Elementary School PAC $4,560.00 District Parent Advisory Council and Parent Advisory Council Abbotsford Chief Dan George Middle School P.A.C.