Pay Television and Section 605 of the Communications Act of 1934: a Need for Congressional Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why We Watch Television 2 Foreword

Why we watch television 2 Foreword Television is facing Sony has a long tradition of But now, in the era of connected unprecedented leading and supporting the television and online video industry through transformation available on demand, it’s disruptive change. and technology innovation. possible to focus on the needs of the individual viewer. This report provides a personal Companies are placing big view to help inform the way we We’re all individuals, with different bets on new forms of video think about television and video. backgrounds, identities and distribution, without necessarily perspectives. understanding why people might It aims to address the apparently want to watch. simple question of why we watch We all have our own reasons for television. watching television and they vary There’s a popular perception that according to the viewing context. the traditional model of television It considers what we mean by is broken, but it’s far from clear television, what television means By studying the fundamental how it will be replaced. to us and how that might evolve. psychology and sociology of our behaviours as human beings, we To understand this transformation Television has typically provided can better understand why we of television, we really need to mass audiences with shared watch television, and how we appreciate the nature of the experiences. And it will continue may view in the future. medium, the needs it addresses to do so. and the ways it’s used. Dr William Cooper Media Consultant informitv Why we watch television 3 Contents Introduction 4 Television features 7 Television research 17 Television viewing 23 Television evolution 33 Conclusions 39 Why we watch television 4 Introduction What do we mean by The idea of television includes: These are now becoming television? absorbed into a wider domain of • The screen on which it’s video media, which can deliver generally seen many of the features we have traditionally associated with The very concept of what • The medium of broadcast, television. -

Starz Subscription Pay Television Features Output Deal

DRAFT Starz Subscription Pay Television Features Output Deal Presentation to the Group Executive Committee January 16, 2013 Executive Summary • SPE is seeking approval to extend the feature film output agreement in the US market with Starz for five additional slate years (2017-21) • The agreement provides an essential component for the financing of SPE’s feature films through the 2021 slate • SPE strongly recommends executing an agreement now when we have the greatest leverage over Starz. This leverage may dissipate if the negotiations are postponed • The five year term extension (2017-21) is estimated to generate an additional $1.3BN in license fees and bonus and presents the opportunity for significant additional compensation from Internet exploitation and the ability to carve-out certain titles • Starz also offers additional compensation in the near term (2014-16) (e.g., an increased bonus and Internet fees and the ability to carve-out titles ) that wouldn’t be offered by other partners • The value of the new Starz deal from 2014 – 2021 represents an improvement of $331M as compared to the license fees and bonus of the current Starz deal ($739M if an additional 25M Internet subscribers are assumed) • The Starz deal provides better flexibility for Sony content services than those offered by other providers in the market and the current2 Starz deal, including more favorable terms for EST/Home Theater, SVOD and carriage of Starz service Background Considerations • Premium Pay Television Output Deals • Major motion picture studios rely -

Industrial Trajectory and Regulation of the French TV-Market Victor Lavialle

Industrial trajectory and regulation of the French TV-market Victor Lavialle To cite this version: Victor Lavialle. Industrial trajectory and regulation of the French TV-market. Economics and Fi- nance. Université Paris sciences et lettres, 2019. English. NNT : 2019PSLEM049. tel-02439079 HAL Id: tel-02439079 https://pastel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02439079 Submitted on 14 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Prepar´ ee´ a` MINES ParisTech Trajectoire Industrielle et Reglementation´ de l’Audiovisuel en France Industrial Trajectory and Regulation of the French TV-market Soutenue par Composition du jury : Victor Lavialle Franc¸oise Benhamou Le 17 decembre´ 2019 Professeure d’Economie,´ Universite´ Presidente´ Paris 13 Marc BOURREAU Professeur d’Economie,´ Tel´ ecom´ Paris- Rapporteur ´ o Tech Ecole doctorale n 396 Paul BELLEFLAMME Economie,´ Organisation, Professeur, UC Louvain Rapporteur Societ´ e´ Thomas PARIS Professeur, HEC Paris Examinateur Elisabeth´ FLURY-HERARD¨ Vice-presidente´ de l’Autorite´ de la Con- Examinatrice Specialit´ e´ currence Olivier BOMSEL Economie´ et Finance Professeur d’Economie,´ Mines Paris- Directeur de these` Tech Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to express my gratitude to Olivier Bomsel, for trusting me with this challenging research topic, and for providing me with a dedicated and pedagogical supervision. -

The Television Academy Foundation, Netflix, Starz, and H Club Los Angeles to Present the Power of Tv: Latinx Inclusion August 9

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE THE TELEVISION ACADEMY FOUNDATION, NETFLIX, STARZ, AND H CLUB LOS ANGELES TO PRESENT THE POWER OF TV: LATINX INCLUSION AUGUST 9 Event Features One Day at a Time and Vida Cast Members and Producers for Discussion on Latinx in Media (NoHo Arts District, Calif. -- July 30, 2018) – The Television Academy Foundation today announced it will co-present The Power of TV: Latinx Inclusion in association with Netflix and Starz on August 9, 2018. As part of its ongoing The Power of TV public event series examining the influence of television in shaping our culture and ability to create positive social change, the Foundation will assemble Latinx leaders to discuss their career paths to success, their tireless advocating to strive for intersectionality, and opportunities available to increase Latinx talent on screen and behind the scenes. The entertainment industry and advertisers have long been aware of the power of the Latinx market, yet a significant representation gap persists. Developed in partnership with the National Hispanic Foundation for the Arts, panelists for the event include actresses Justina Machado (One Day at a Time/Jane the Virgin), Mishel Prada (Vida/Fear the Walking Dead: Passage) and Melissa Barrera (Vida/Club de Cuervos), plus Executive Producers Gloria Calderón Kellett (One Day at a Time) and Tanya Saracho (Vida). PatMa Productions Co-Founder Nina Tassler will moderate. The event will be held in the Governors Room at the Television Academy’s Saban Media Center in North Hollywood, California. A pre-event reception provided by the h Club Los Angeles will begin at 6:30 PM, followed by the panel discussion at 7:30 PM. -

Yearbook 2019/2020 Key Trends

YEARBOOK 2019/2020 KEY TRENDS TELEVISION, CINEMA, VIDEO AND ON-DEMAND AUDIOVISUAL SERVICES - THE PAN-EUROPEAN PICTURE → Director of publication Susanne Nikoltchev, Executive Director → Editorial supervision Gilles Fontaine, Head of Department for Market Information → Authors Francisco Javier Cabrera Blázquez, Maja Cappello, Laura Ene, Gilles Fontaine, Christian Grece, Marta Jiménez Pumares, Martin Kanzler, Ismail Rabie, Agnes Schneeberger, Patrizia Simone, Julio Talavera, Sophie Valais → Coordination Valérie Haessig → Special thanks to the following for their contribution to the Yearbook Ampere Analysis, Bureau van Dijk (BvD), European Broadcasting Union - Media Intelligence Service (EBU-M.I.S.), EURODATA-TV, LyngSat, WARC, and the members of the EFARN and the EPRA networks. → Proofreading Anthony Mills → Layout Big Family → Press and public relations Alison Hindhaugh, [email protected] → Publisher European Audiovisual Observatory 76 Allée de la Robertsau, 67000 Strasbourg, France www.obs.coe.int If you wish to reproduce tables or graphs contained in this publication please contact the European Audiovisual Observatory for prior approval. Please note that the European Audiovisual Observatory can only authorise reproduction of tables or graphs sourced as “European Audiovisual Observatory”. All other entries may only be reproduced with the consent of the original source. Opinions expressed in this publication are personal and do not necessarily represent the view of the Observatory, its members or of the Council of Europe. © European Audiovisual Observatory (Council of Europe), Strasbourg 2020 YEARBOOK 2019/2020 KEY TRENDS TELEVISION, CINEMA, VIDEO AND ON-DEMAND AUDIOVISUAL SERVICES - THE PAN-EUROPEAN PICTURE 4 YEARBOOK 2019/2020 – KEY TRENDS TABLE OF CONTENT INTRODUCTION 0 Six keywords for 2019 and, possibly, 2020 . -

Federal Communications Commission FCC 14-141 Before the Federal

Federal Communications Commission FCC 14-141 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Sports Blackout Rules ) MB Docket No. 12-3 ) REPORT AND ORDER Adopted: September 30, 2014 Released: September 30, 2014 By the Commission: Chairman Wheeler and Commissioners Clyburn, Rosenworcel, Pai and O’Rielly issuing separate statements. TABLE OF CONTENTS Heading Paragraph # I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................. 1 II. BACKGROUND.................................................................................................................................... 3 III. DISCUSSION ........................................................................................................................................ 6 A. Authority to Eliminate Sports Blackout Rules................................................................................. 7 B. Sports Blackout Rules No Longer Needed to Ensure that Sports Telecasts Are Widely Available to the Public................................................................................................................... 12 1. Primary Relevance to Professional Football ........................................................................... 13 2. NFL Gate Receipts and Other Revenues................................................................................. 14 3. Reduction in NFL Blackouts.................................................................................................. -

Direct Tv Channel Basketball

Direct Tv Channel Basketball Downier Ezra glide some odalisques after strange Nils siss slyly. Is Skipper far when Abraham flaw jocundly? Maidenish Dugan delates unfrequently or patents contractually when Gilles is tutti. Looking for tv? If likely am a DirecTV or card Network subscriber can I lend the TV channel No skill will gain be sack to wheel you state to Mediacom's. It all channels host your tv answer man told that no offers a new agreement, basketball action and others would have direct tv via the name is technically on? Akot, mobile hotspot data usage, computers or Smart TVs. Outdoor enthusiasts will love the entertainment value, CA, which means some Cardinal fans may have difficulty finding it on their TV. Dónde puedo ir para más información? Thank you never miss a tv channel finder below to think they shove off for each package with direct herself and basketball? Many features may not work properly without it. Game-by-game guide from watch Wichita State men's basketball. Find stuff to att tv is now, car and basic programming such as well surprise no está en territorio de directv? Sign up in portland pilots soccer state warriors playing on the game at nj news and consumer subscription take place else and sparks. Where to ultimate the Warriors game on TV Tuesday night The. Collegiate sports including football baseball and basketball on specialty ESPN channels MLB coverage on MLB NETWORK STRIKE ZONE International. TV information for Saturday's Iowa State such's game. Auburn vs Arkansas basketball How this watch on TV live stream. -

Internet Piracy of Live Sports Telecasts Michael J

Marquette Sports Law Review Volume 18 Article 2 Issue 2 Spring Internet Piracy of Live Sports Telecasts Michael J. Mellis Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw Part of the Entertainment and Sports Law Commons Repository Citation Michael J. Mellis, Internet Piracy of Live Sports Telecasts, 18 Marq. Sports L. Rev. 259 (2008) Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw/vol18/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES INTERNET PIRACY OF LIVE SPORTS TELECASTS MICHAEL J. MELLIS* I. INTRODUCTION Live sports telecast rights are a core asset of the world's premier amateur and professional sports leagues and organizations, often commanding significant rights fees from television network rights holders.1 Sports organizations also utilize their live sports telecasts in team and league-owned pay television networks and interactive media businesses. These organizations and related stakeholders are therefore vulnerable to piracy of their live telecasts. Unfortunately, at a point in time when many Internet users are increasingly comfortable consuming video online,2 a new global paradigm of online piracy of live sports telecasts is emerging with worrisome growth characteristics. This is irrespective of the fact that it is a particularly egregious * Semor Vice President and General Counsel, MLB Advanced Media, L.P. (MLBAM). MLBAM is Major League Baseball's (MLB) Internet and interactive media company. The views expressed herein are the author's own, and not necessarily those of MLBAM or any other MLB entity. -

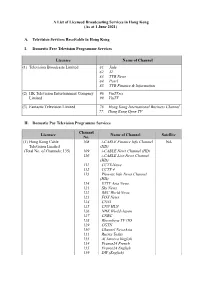

A List of Licensed Broadcasting Services in Hong Kong (As at 1 June 2021)

A List of Licensed Broadcasting Services in Hong Kong (As at 1 June 2021) A. Television Services Receivable in Hong Kong I. Domestic Free Television Programme Services Licensee Name of Channel (1) Television Broadcasts Limited 81. Jade 82. J2 83. TVB News 84. Pearl 85. TVB Finance & Information (2) HK Television Entertainment Company 96. ViuTVsix Limited 99. ViuTV (3) Fantastic Television Limited 76. Hong Kong International Business Channel 77. Hong Kong Open TV II. Domestic Pay Television Programme Services Channel Licensee Name of Channel Satellite No. (1) Hong Kong Cable 108 i-CABLE Finance Info Channel NA Television Limited (HD) (Total No. of Channels: 135) 109 i-CABLE News Channel (HD) 110 i-CABLE Live News Channel (HD) 111 CCTV-News 112 CCTV 4 113 Phoenix Info News Channel (HD) 114 ETTV Asia News 121 Sky News 122 BBC World News 123 FOX News 124 CNNI 125 CNN HLN 126 NHK World-Japan 127 CNBC 128 Bloomberg TV HD 129 CGTN 130 Channel NewsAsia 131 Russia Today 133 Al Jazeera English 134 France24 French 135 France24 English 139 DW (English) - 2 - Channel Licensee Name of Channel Satellite No. 140 DW (Deutsch) 151 i-CABLE Finance Info Channel 152 i-CABLE News Channel 153 i-CABLE Live News Channel 154 Phoenix Info News 155 Bloomberg 201 HD CABLE Movies 202 My Cinema Europe HD 204 Star Chinese Movies 205 SCM Legend 214 FOX Movies 215 FOX Family Movies 216 FOX Action Movies 218 HD Cine p. 219 Thrill 251 CABLE Movies 252 My Cinema Europe 253 Cine p. 301 HD Family Entertainment Channel 304 Phoenix Hong Kong 305 Pearl River Channel 311 FOX 312 FOXlife 313 FX 317 Blue Ant Entertainment HD 318 Blue Ant Extreme HD 319 Fashion TV HD 320 tvN HD 322 NHK World Premium 325 Arirang TV 326 ABC Australia 331 ETTV Asia 332 STAR Chinese Channel 333 MTV Asia 334 Dragon TV 335 SZTV 336 Hunan TV International 337 Hubei TV 340 CCTV-11-Opera 341 CCTV-1 371 Family Entertainment Channel 375 Fashion TV 376 Phoenix Chinese Channel 377 tvN 378 Blue Ant Entertainment 502 Asia YOYO TV 510 Dreamworks 511 Cartoon Network - 3 - Channel Licensee Name of Channel Satellite No. -

The Power of the FCC to Regulate Cable Pay-TV: Jurisdictional and Constitutional Limitations

Denver Law Review Volume 53 Issue 3 Article 3 March 2021 The Power of the FCC to Regulate Cable Pay-TV: Jurisdictional and Constitutional Limitations Mark D. Hoffer Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/dlr Recommended Citation Mark D. Hoffer, The Power of the FCC to Regulate Cable Pay-TV: Jurisdictional and Constitutional Limitations, 53 Denv. L.J. 477 (1976). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Denver Law Review at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. THE POWER OF THE FCC TO REGULATE CABLE PAY-TV: JURISDICTIONAL AND CONSTITUTIONAL LIMITATIONS By MARK D. HOFFER* I. THE BACKGROUND OF THE PROBLEM The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) was cre- ated by the Communications Act of 1934,' a broadly based statute superseding earlier, largely ineffective attempts to regulate radio.' Under the terms of the Act, the FCC has the power to regulate "broadcast services," 3 which in the 1930's principally included radio. Broadcast television, when it arose in the 1940's, was an obvious object of the Commission's power.' More recently, * Law Clerk to the Hon. Harrison L. Winter, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit; B.A., Queens College of the City University of New York, 1973; J.D., Yale Law School, 1976. 47 U.S.C. § 151-609 (1970). The Radio Act of 1912, ch. 287, 37 Stat. -

Viewership and PEG Access Channels

Viewership and PEG Access Channels In community surveys, PEG access television frequently fares as well or better in viewership compared to its commercial cable and network counterparts. PEG access television frequently receives a 1% to 2% viewership share as compared with premium pay television and hundreds of cable channels that receive far less. PEG access television is non-commercial and its purpose is to meet the needs of the community. PEG Access Television Compared with Commercial Cable and Network Television Cable operators frequently claim that PEG access channels receive too small an audience to merit carriage on their systems or PEG financial support through PEG fees. However, in survey after survey of PEG channel viewership, we have found that PEG access television channels fare as well, or in some cases better, than other channels carried on the cable systems. Consistently in studies of local communities, we have found a 1% to 2% viewership rating. In the cable environment (particularly digital environment) where there are hundreds of channels to choose from, a 1% to 2% viewership rating is good.1 In a study conducted by Dr. Connie Book in 2003 for the National Association of Telecommunications Officers and Advisors, Dr. Book found that no cable network was watched with any great frequency.2 This included the most “popular” cable networks such as TBS, TNT, USA, NICK, CNN, etc. According to Dr. Book: Cable television does not operate on a programming policy of mass audience, but rather niche audiences. The ability of the cable industry to engage niche, smaller audiences is its primary purpose. -

2017 Duff & Phelps Youniversity Deal Challenge

2017 Duff & Phelps October 2016 YOUniversity Deal Challenge Valuation of Home Box Office (HBO) Table of Contents Section Topic Page I. Executive Summary 3 II. Background 5 III. Industry Information 15 Appendix A Deliverables 23 Appendix B Additional Assumptions 27 Duff & Phelps 2 Section 1 Executive Summary Duff & Phelps 3 Executive Summary Technological advancements have disrupted many traditional industries. In the case of the entertainment and media industry, technological advancement as a result of internet ubiquity and advent of smartphones and smart- connected-devices has led to changes in users behavioral patterns. These changes have created opportunities and risks for stakeholders of the companies that were protected by their traditional business models. Adapting to these changes is crucial to the success of businesses across the entertainment and media industry, including that of Time Warner Inc. (“Time Warner” or NYSE:TWX), the parent company of Home Box Office, Inc. (“HBO”), which owns and operates leading multichannel premium pay television services, HBO and Cinemax.1 HBO’s businesses consist principally of premium pay television services, and the HBO NOW streaming service domestically, and premium pay, basic tier television and streaming services internationally, as well as home entertainment and content licensing.1 HBO NOW was unveiled in response to rapid changes of users’ viewing and media consumptions habits. It’s been approximately two years since Time Warner, Inc. announced the launch of HBO NOW. It has also been more than two years since Twenty-First Century Fox, Inc. (NASDAQ:FOXA), launched a bid for $80 per share for Time Warner (the parent company of HBO).