Emerging Culture Patterns in American Jewish Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moses Hayim Luzzatto's Quest for Providence

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 'Like Iron to a Magnet': Moses Hayim Luzzatto's Quest for Providence David Sclar Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/380 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] “Like Iron to a Magnet”: Moses Hayim Luzzatto’s Quest for Providence By David Sclar A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The City University of New York 2014 © 2014 David Sclar All Rights Reserved This Manuscript has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Prof. Jane S. Gerber _______________ ____________________________________ Date Chair of the Examining Committee Prof. Helena Rosenblatt _______________ ____________________________________ Date Executive Officer Prof. Francesca Bregoli _______________________________________ Prof. Elisheva Carlebach ________________________________________ Prof. Robert Seltzer ________________________________________ Prof. David Sorkin ________________________________________ Supervisory Committee iii Abstract “Like Iron to a Magnet”: Moses Hayim Luzzatto’s Quest for Providence by David Sclar Advisor: Prof. Jane S. Gerber This dissertation is a biographical study of Moses Hayim Luzzatto (1707–1746 or 1747). It presents the social and religious context in which Luzzatto was variously celebrated as the leader of a kabbalistic-messianic confraternity in Padua, condemned as a deviant threat by rabbis in Venice and central and eastern Europe, and accepted by the Portuguese Jewish community after relocating to Amsterdam. -

American Jewish Yearbook

JEWISH STATISTICS 277 JEWISH STATISTICS The statistics of Jews in the world rest largely upon estimates. In Russia, Austria-Hungary, Germany, and a few other countries, official figures are obtainable. In the main, however, the num- bers given are based upon estimates repeated and added to by one statistical authority after another. For the statistics given below various authorities have been consulted, among them the " Statesman's Year Book" for 1910, the English " Jewish Year Book " for 5670-71, " The Jewish Ency- clopedia," Jildische Statistik, and the Alliance Israelite Uni- verselle reports. THE UNITED STATES ESTIMATES As the census of the United States has, in accordance with the spirit of American institutions, taken no heed of the religious convictions of American citizens, whether native-born or natural- ized, all statements concerning the number of Jews living in this country are based upon estimates. The Jewish population was estimated— In 1818 by Mordecai M. Noah at 3,000 In 1824 by Solomon Etting at 6,000 In 1826 by Isaac C. Harby at 6,000 In 1840 by the American Almanac at 15,000 In 1848 by M. A. Berk at 50,000 In 1880 by Wm. B. Hackenburg at 230,257 In 1888 by Isaac Markens at 400,000 In 1897 by David Sulzberger at 937,800 In 1905 by "The Jewish Encyclopedia" at 1,508,435 In 1907 by " The American Jewish Year Book " at 1,777,185 In 1910 by " The American Je\rish Year Book" at 2,044,762 DISTRIBUTION The following table by States presents two sets of estimates. -

Aliyah and Settlement Process?

Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel HBI SERIES ON JEWISH WOMEN Shulamit Reinharz, General Editor Joyce Antler, Associate Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor The HBI Series on Jewish Women, created by the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, pub- lishes a wide range of books by and about Jewish women in diverse contexts and time periods. Of interest to scholars and the educated public, the HBI Series on Jewish Women fills major gaps in Jewish Studies and in Women and Gender Studies as well as their intersection. For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www.upne.com and www.upne.com/series/BSJW.html. Ruth Kark, Margalit Shilo, and Galit Hasan-Rokem, editors, Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel: Life History, Politics, and Culture Tova Hartman, Feminism Encounters Traditional Judaism: Resistance and Accommodation Anne Lapidus Lerner, Eternally Eve: Images of Eve in the Hebrew Bible, Midrash, and Modern Jewish Poetry Margalit Shilo, Princess or Prisoner? Jewish Women in Jerusalem, 1840–1914 Marcia Falk, translator, The Song of Songs: Love Lyrics from the Bible Sylvia Barack Fishman, Double or Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed Marriage Avraham Grossman, Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Medieval Europe Iris Parush, Reading Jewish Women: Marginality and Modernization in Nineteenth-Century Eastern European Jewish Society Shulamit Reinharz and Mark A. Raider, editors, American Jewish Women and the Zionist Enterprise Tamar Ross, Expanding the Palace of Torah: Orthodoxy and Feminism Farideh Goldin, Wedding Song: Memoirs of an Iranian Jewish Woman Elizabeth Wyner Mark, editor, The Covenant of Circumcision: New Perspectives on an Ancient Jewish Rite Rochelle L. -

The Influence of Anti-Semitism on United States Immigration Policy with Respect to German Jews During 1933-1939

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2011 The Influence of Anti-Semitism on United States Immigration Policy With respect to German Jews During 1933-1939 Barbara L. Bailin CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/262 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Influence of Anti-Semitism on United States Immigration Policy With Respect to German Jews during 1933-1939 By Barbara L. Bailin Advisors: Prof. Craig A. Daigle and Prof. Andreas Killen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts the City College of the City University of New York May 10, 2011 Table of Contents Page Introduction . 1 Chapter I The History of the LPC Provision . 14 Chapter II The Visa Application Process and the LPC Provision . 22 Chapter III Anti-Semitism in the State Department . 44 Chapter IV There was No Merit to the Arguments Advanced by State Department Officials in Support of the Restrictive Issuance of Visas to German Jews . 60 Conclusion . 76 Introduction During the period 1933-1939, many German Jews sought to escape Nazi anti-Semitism and persecution by immigrating to the United States as well as to other countries.1 In the United States, the four government officials who con- trolled American immigration policy with respect to Germany were themselves anti-Semitic. -

THE YIDDISH PRESS—AN AMERICANIZING AGENCY It Is

THE YIDDISH PRESS—AN AMERICANIZING AGENCY By MORDECAI SOLTES, PH.D. Director, Extension Education, Bureau of Jewish Education, New York INTRODUCTION It is generally agreed that there is a great need to-day for civic instruction which will function more effectively. Our life and needs are becoming more complex; our stand- ards of civic behavior are being constantly revised upwards, and the civic responsibilities which our citizens must dis- charge are becoming increasingly difficult. Education for citizenship should occupy a central position in the public school curriculum. The civic pos- sibilities of all the school subjects should be utilized to a maximum, and the specific ideals of citizenship should become the possession of the pupils as a result of their entire school training and activity. In addition there should be provided, wherever neces- sary, aside from the general courses, supplementary in- struction to meet specific needs of pupils, which shall have been ascertained beforehand. This suggestion applies with particular force to schools which are located in neighborhoods of comparatively large immigrant populations. Wherever fairly homogeneous groups of children could be located, 166 AMERICAN JEWISH YEAR BOOK it would prove best to make a diagnosis of the civic virtues ;ind deficiencies of the corresponding adult group, to es- tablish their prevailing civic characteristics, both favorable and unfavorable, and to develop, on the basis of the out- standing needs revealed, special supplementary courses that would tend to prevent or correct the expected short- comings, to improve the desirable traits and approved qualities which are insufficiently or wrongly developed, and to capitalize fully the civic potentialities of the younger generation. -

The Weekly Daf · World Wide Web: Our Address Is Is Available from · Fax and Mail in Israel and US-MAIL in America

Week of 2-8 Tamuz 5757 / 7-13 July 1997 Rav Weinbach's insights, explanations and comments for the 7 pages of Talmud Tamid 26-32 studied in the course of the worldwide Daf Yomi cycle Races and Lotteries The first sacred service performed daily in the Beis Hamikdash was the ceremonial removal of some of the ashes from the altar by a single kohen. The first Mishnah in Mesechta Tamid, which deals with the regular system of service, informs us that any kohen who was interested in performing this service would purify himself by immersion in a mikveh before the arrival of the kohen in charge of delegating duties. When he arrived he would announce that anyone who had already immersed himself in anticipation of the privilege to perform this first service should come forward and participate in a lottery to choose the privileged one from amongst all who were candidates. Conflicting signals seem to emerge from this Mishnah. The initial indication is that no lottery was used to determine who would perform the service, because if a lottery would decide the matter why should an interested kohen bother with immersion before he even knew whether he would be chosen. The concluding words of the Mishnah, however, indicate that a lottery was definitely required. Two resolutions are proposed. The Sage Rava explains that even though each kohen who immersed himself realized he might lose out in the lottery, he did so in order to be immediately ready to perform the service if he indeed was privileged to be chosen. -

The Role of Religion in American Jewish Satire

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE 1-1-2015 All Joking Aside: The Role of Religion in American Jewish Satire Jennifer Ann Caplan Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Caplan, Jennifer Ann, "All Joking Aside: The Role of Religion in American Jewish Satire" (2015). Dissertations - ALL. 322. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/322 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT Jewish humor is a well-known, if ill-defined genre. The prevalence and success of Jewish comedians has been a point of pride for American Jews throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. What I undertake in this dissertation is to isolate one particular form of humor—namely satire—and use it as a way to analyze the changing relationship of American Jews to traditional religious forms. I look at the trends over three generations, the third generation (who came of age in the 40s and 50s), the Baby Boom generation (who came of age in the 60s and 70s) and the contemporary generation (who came of age in the 80s and 90s). When the satire produced by each generation is analyzed with the depiction of Judaism and Jewish practices in mind a certain pattern emerges. By then reading that pattern through Bill Brown’s Thing Theory it becomes possible to talk about the motivations for and effects of the change over time in a new way. -

KMS Sefer Minhagim

KMS Sefer Minhagim Kemp Mill Synagogue Silver Spring, Maryland Version 1.60 February 2017 KMS Sefer Minhagim Version 1.60 Table of Contents 1. NOSACH ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 RITE FOR SERVICES ............................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 RITE FOR SELICHOT ............................................................................................................................................ 1 1.3 NOSACH FOR KADDISH ....................................................................................................................................... 1 1.4 PRONUNCIATION ............................................................................................................................................... 1 1.5 LUACH ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 2. WHO MAY SERVE AS SH’LIACH TZIBUR .......................................................................................................... 2 2.1 SH’LIACH TZIBUR MUST BE APPOINTED .................................................................................................................. 2 2.2 QUALIFICATIONS TO SERVE AS SH’LIACH TZIBUR ..................................................................................................... -

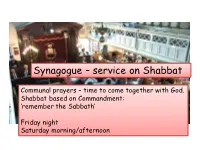

Synagogue – Service on Shabbat

Synagogue – service on Shabbat Communal prayers – time to come together with God. Shabbat based on Commandment: ‘remember the Sabbath’ Friday night Saturday morning/afternoon Shema Prayers – include Shema, Amidah, reading from the Torah, sermon from Rabbi, use SIDDUR Amidah (order of service) ‘Keep Sabbath holy..’ Commandment Siddur Orthodox – Reform – Service in Hebrew Use own language + Hebrew Unaccompanied songs No reference to Messiah/resurrection Men and women apart Use instruments/recorded music Men and women together AMIDAH .. Core prayer of every Jewish service, it means STANDING 18 blessings Prayer is thePraise bridge God between man and God Prayer daily part of life – Shema Praise/thanksgiving/requestsRequests from God Thanksgiving Recited silently + read by rabbi At the end take 3 steps back /forward (Reform don’t do). Symbolise Whole volume in TALMUD aboutwithdrawing prayer: from God’s presence... BERAKHOT 39 categories of not working – include no SHABBAT: Importantcooking = What happens? ONLY PIKUACH NEFESH = save a 1. Celebrates God’s Prepare home – clean/cook life work can be doneBegins 18 mins before creation (Gen OrthodoxIn don't drive, sunset (Fri) the beginning ..)live near synagogue – Mother lights two candles – Reform do drive have 2. Time of spiritual Shekinah car parks renewal – family Blessing over a loaf Best food served, time Kiddush prayer over wine best crockery, food (‘Blessed are you our God..’ pre-prepared. 3. It is one of the Attend synagogue (Sat) Ten Orthodox follow rules literally – electric Havdalah candle lit – ends CommandmentslightsIs this on timers out of date?Shabbat, holy and world are (keep it holy) Non-orthodox it’s not mixed. -

Mez.Iz.Ah Be-Peh―Therapeutic Touch Or Hippocratic Vestige?1

15 Meziẓ aḥ be-Peh―Therapeutic Touch or Hippocratic Vestige? 1 By: SHLOMO SPRECHER With the appearance of a news article in the mass-circulation New York Daily News2 implicating meziẓ aḥ be-peh3 in the death of a Brooklyn 1 The author wishes to emphasize that he subscribes fully to the principle that an individual’s halakhic practice should be determined solely by that individual’s posek. Articles of this nature should never be utilized as a basis for changing one’s minhag. This work is intended primarily to provide some historical background. It may also be used by those individuals whose poskim mandate use of a tube instead of direct oral contact for the performance of meziẓ aḥ , but are still seeking additional material to establish the halakhic bona fides of this ruling. Furthermore, the author affirms that the entire article is predicated only on “Da’at Ba’alei Battim.” 2 February 2, 2005, p. 7. 3 I am aware that purists of Hebrew will insist that the correct vocalization should be be-feh. However, since all spoken references I’ve heard, and all the published material I’ve read, use the form “be-peh,” I too will follow their lead. I believe that a credible explanation for this substitution is a desire to avoid the pejorative sense of the correct vocalization. Lest the reader think that Hebrew vocalization is never influenced by such aesthetic considerations, I can supply proof to the contrary. The Barukh she-’Amar prayer found in Tefillat Shahariṭ contains the phrase “be-feh ‘Amo.” Even a novice Hebraist can recognize that the correct formulation should be in the construct state―“be-fi ‘Amo.” Although many have questioned this apparent error, Rabbi Yitzchak Luria’s supposed endorsement of this nusah ̣ has successfully parried any attempts to bring it into conformity with the established rules of Hebrew grammar. -

HIAS-JCA Emigration Association (HICEM), Paris (Fond 740) RG-11.001M.94

HIAS-JCA Emigration Association (HICEM), Paris (Fond 740) RG-11.001M.94 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archives 100 Raoul Wallenberg Place SW Washington, DC 20024-2126 Tel. (202) 479-9717 e-mail: [email protected] Descriptive summary Title: HIAS-JCA Emigration Association (HICEM), Paris (Fond 740) Dates: 1906-1941 (inclusive) 1926-1941 (bulk) Accession number: 2006.515.12 Creator: Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS)-HICEM Extent: 137 microfilm reels (partial) Ca. 240,000 digital images Repository: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archives, 100 Raoul Wallenberg Place SW, Washington, DC 20024-2126 Languages: French German English Hebrew Scope and content of collection Administrative files of the council of HICEM, including minutes, reports of the HICEM’s bureau of statistics, and finance department, circulars, and field trip reports. Other materials include reports on the status of Jews in various countries, lists of emigrants, reports on conferences, including minutes taken at the 1938 Evian conference, bulletins and periodicals issued by HICEM, press and media clippings, correspondence with branches and organizations in various countries, including correspondence with local HICEM branches, local charities and Jewish communities, correspondences with international organizations like the League of Nations, OZE, and the Jewish Child Welfare Organization. These records consist of materials left in Paris when the HICEM offices were moved to Bordeaux in 1940, before being transferred to Marseille and ultimately Lisbon for the duration of the war. Files that HICEM official took with them when the Paris office closed in June 1940 can be found at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research (RG 245.5; http://findingaids.cjh.org/?pID=1309366; accessed 11 March 2019). -

RITES of PASSAGE - MARRIAGE Starter: Recall Questions 1

Thursday, January 28, 2021 RITES OF PASSAGE - MARRIAGE Starter: Recall Questions 1. What does a Sandek do in Judaism? 2. What is the literal translation of bar mitzvah? 3. A girl becomes a bat mitzvah at what age? 4. Under Jewish law, children become obligated to observe the what of Jewish law after their bar/bat mitzvah 5. What is the oral law? All: To examine marriage trends in the Learning 21st century. Intent Most: To analyse the most important customs and traditions in a Jewish marriage ceremony. Some: assess the difference in the approach on marriage in Jewish communities/ consider whether marriage is relevant in the 21 century. Key Terms for this topic 1. Adultery: Sexual intercourse between a married person and another person who is not their spouse. 2. Agunah: Women who are 'chained' metaphorically because their husbands have not applied for a 'get' or refused to give them one. 3. Ashkenazi Jew:A Jew who has descended from traditionally German-speaking countries in Central and Eastern Europe. 4. Chuppah: A canopy used during a Jewish wedding. It is representative of the couple’s home. 5. Cohabitation: Living together without being married. 6. Conservative: These are believers that prefer to keep to old ways and only reluctantly allow changes in traditional beliefs and practices. 7. Divorce: A legal separation of the marriage partners. 8. family purity: A system of rules observed by Jews whereby husband and wife do not engage in sexual relations or any physical contact from the onset of menstruation until 7 days after its end and the woman has purified herself at the mikvah.