Calling All Clowns - a Creative Project and a Personal Journey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Resurrection of Nora O'brien

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Spring 2019 The Resurrection of Nora O'Brien Abigail Elizabeth Benson Missouri State University, [email protected] As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the Fiction Commons Recommended Citation Benson, Abigail Elizabeth, "The Resurrection of Nora O'Brien" (2019). MSU Graduate Theses. 3404. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3404 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RESURRECTION OF NORA O’BRIEN A Master’s Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University TEMPLATE In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts, English By Abigail Elizabeth Benson May 2019 THE RESURRECTION OF NORA O’BRIEN English Missouri State University, May 2019 Master of Arts Abigail Elizabeth Benson ABSTRACT There is a cave, hidden in the hills, that brings the dead back to life. Its power is the driving force behind the blood feud between the Walshes and the O’Briens that lasts for generations. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

William Slade Stokes Magnolias Charleston, South Carolina *** Date

William Slade Stokes Magnolias Charleston, South Carolina *** Date: August 14, 2019 Location: Magnolias, Charleston SC Transcription: Technitype Transcripts Length: Forty nine minutes Project: Career Servers Slade Stokes— Charleston, SC |1 Annemarie Anderson: Today is August 14th [2019]. It is Wednesday. I’m at Magnolias with Mr. Slade Stokes, and this is Annemarie Anderson recording for the Southern Foodways Alliance Career Servers Project. Let’s start off and, Mr. Stokes, would you please introduce yourself to the recorder, tell us who you are and what you do. [0:00:20.5] Slade Stokes: Hi, my name is Slade Stokes. I am a server at Magnolias Restaurant in Charleston, South Carolina. October 12th will be my twentieth anniversary here and started here October of [19]99. I had worked at another restaurant before that, called Celia’s Porta Via’s, a small Italian restaurant, and she retired. A friend of mine who had worked here had set up employment with one of the managers, and at the time they said they weren’t hiring, but they liked me so much, they put me on the schedule. [0:01:00.2] Annemarie Anderson: That’s great. Well, tell me a little bit. Let’s start off and would you give your birth date for the record, please. [0:01:07.4] Slade Stokes: February 15th, 1960. [0:01:09.8] © Southern Foodways Alliance | www.southernfoodways.org Slade Stokes— Charleston, SC |2 Annemarie Anderson: Great. And tell me a little bit about your early life. Where were you born and raised? [0:01:15.0] Slade Stokes: I was born in Hickman, Kentucky, spent my first few years there in Kentucky with my brother and my two sisters and my mom. -

Gayle Lajoye Interviewed by Philip Mfulks 116 Ridge St

Interview with Gayle LaJoye Interviewed by Philip MFulks 116 Ridge St. Marquette, Michigan 4.22.1981 Start of interview (P) Mr. LaJoye what is your profession? (G) Well I worked as a clown for the circuses and now I’m working as a clown on stage, pretty much doing instead of circus clowning I’m doing clowning which is more indicative to the stage and has a greater structure. There’s a lot of difference in both types of clowning. (P) I see. So then you are working independently rather than with a circus or anything like that? (G) Yes I’m trying to do shows on a college circuit and nightclubs and things like that. But I’m trying to take the clowning from the circus which was more a popular entertainment thing but yet it’s still an art form into more of a serious theater piece where it has a beginning middle and an end. (P) How did you become involved with clowning? (G) I was involved with theater at Northern Michigan University and I tried doing a few things around in school and found that I had a pretty good ability for acting and I got involved in theater and I worked in a few of the play and got real good support from the public and my teachers. And I decided that I wanted to instead of going on into the university, I was getting kind of tired college so I decided to maybe go into a professional field, more like popular entertainment and try and take classes while I was doing and move into acting in either a large city or whatever areas I had go to do that. -

The Children of Molemo: an Analysis of Johnny Simons' Performance Genealogy and Iconography at the Hip Pocket Theatre

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2000 The hiC ldren of Molemo: an Analysis of Johnny Simons' Performance Genealogy and Iconography at the Hip Pocket Theatre. Tony Earnest Medlin Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Medlin, Tony Earnest, "The hiC ldren of Molemo: an Analysis of Johnny Simons' Performance Genealogy and Iconography at the Hip Pocket Theatre." (2000). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7281. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7281 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Linguistic Variation of the American Circus

Abstract http://www.soa.ilstu.edu/anthropology/theses/burns/index.htm Through the "Front Door" to the "Backyard": Linguistic Variation of the American Circus Lisa Burns Illinois State University Anthropology Department Dr. James Stanlaw, Advisor May 1, 2003 Abstract The language of circus can be interpreted through two perspectives: the Traditional American Circus and the New American Circus. There is considerable anthropological importance and research within the study of spectacle and circus. However, there is a limited amount of academic literature pertaining to the linguistics and semiotics of circus. Through participant observation and interviewing, of both circus and non-circus individuals, data will be acquired and analyzed. Further research will provide background information of both types of circuses. Results indicate that an individual's preference can be determined based on the linguistic and semiotic terms used when describing the circus. Introduction Throughout my life, I have always been intrigued by the circus. As a result, I joined the Gamma Phi Circus, here at Illinois State University, in order to obtain a better understanding of circus in our culture. A brief explanation of the title is useful in understanding my paper. I chose the title "Through the 'Front Door' to the 'Backyard'" because "front door" is circus lingo for the doors that a person goes through on entering the tent. The word "backyard" refers to the area in which behind the tent where all the people in the production of the circus park their trailers. This title encompasses the range of information that I have gathered from performers, to directors, to audience members. -

PLAYNOTES Season: 43 Issue: 04

PLAYNOTES SEASON: 43 ISSUE: 04 PORTLANDSTAGE BACKGROUND INFORMATION The Theater of Maine INTERVIEWS & COMMENTARY www.portlandstage.org AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY Discussion Series The Artistic Perspective, hosted by Artistic Director Anita Stewart, is an opportunity for audience members to delve deeper into the themes of the show through conversation with special guests. A different scholar, visiting artist, playwright, or other expert will join the discussion each time. The Artistic Perspective discussions are held after the first Sunday matinee performance. Page to Stage discussions are presented in partnership with the Portland Public Library. These discussions, led by Portland Stage artistic staff, actors, directors, and designers answer questions, share stories and explore the challenges of bringing a particular play to the stage. Page to Stage occurs at noon on the Tuesday after a show opens at the Portland Public Library’s Main Branch. Feel free to bring your lunch! Curtain Call discussions offer a rare opportunity for audience members to talk about the production with the performers. Through this forum, the audience and cast explore topics that range from the process of rehearsing and producing the text to character development to issues raised by the work Curtain Call discussions are held after the second Sunday matinee performance. All discussions are free and open to the public. Show attendance is not required. To subscribe to a discussion series performance, please call the Box Office at 207.774.0465. Portland Stage Company Educational Programs are generously supported through the annual donations of hundreds of individuals and businesses, as well as special funding from: The Davis Family Foundation Funded in part by a grant from our Educational Partner, the Maine Arts Commission, an independent state agency supported by the National Endowment for the Arts. -

From Femme Ideale to Femme Fatale: Contexts for the Exotic Archetype In

From Femme Idéale to Femme Fatale: Contexts for the Exotic Archetype in Nineteenth-Century French Opera A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music by Jessica H. Grimmer BM, University of Cincinnati June 2011 Committee chair: Jonathan Kregor, PhD i ABSTRACT Chromatically meandering, even teasing, Carmen’s Seguidilla proves fatally seductive for Don José, luring him to an obsession that overrides his expected decorum. Equally alluring, Dalila contrives to strip Samson of his powers and the Israelites of their prized warrior. However, while exotic femmes fatales plotting ruination of gentrified patriarchal society populated the nineteenth-century French opera stages, they contrast sharply with an eighteenth-century model populated by merciful exotic male rulers overseeing wandering Western females and their estranged lovers. Disparities between these eighteenth and nineteenth-century archetypes, most notably in treatment and expectation of the exotic and the female, appear particularly striking given the chronological proximity within French operatic tradition. Indeed, current literature depicts these models as mutually exclusive. Yet when conceptualized as a single tradition, it is a socio-political—rather than aesthetic—revolution that provides the basis for this drastic shift from femme idéale to femme fatale. To achieve this end, this thesis contains detailed analyses of operatic librettos and music of operas representative of the eighteenth-century French exotic archetype: Arlequin Sultan Favorite (1721), Le Turc généreux, an entrée in Les Indes Galantes (1735), La Recontre imprévue/Die Pilgrime von Mekka (1764), and Die Entführung aus dem Serail (1782). -

Tilburg University a Pastoral Psychology of Lament Blaine

Tilburg University A pastoral psychology of lament Blaine-Wallace, W. Publication date: 2009 Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Blaine-Wallace, W. (2009). A pastoral psychology of lament. [s.n.]. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. okt. 2021 A Pastoral Psychology of Lament A PASTORAL PSYCHOLOGY OF LAMENT Pastoral Method-Priestly Act-Prophetic Witness Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Tilburg, op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof.dr. Ph. Eijlander, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties aangewezen commissie in de aula van de Universiteit op maandag 15 juni 2009 om 14.15 uur door William Blaine-Wallace geboren op 22 mei 1951 te Salisbury, North Carolina, USA 2 A Pastoral Psychology of Lament Promotores Prof. -

Season 5 Article

N.B. IT IS RECOMMENDED THAT THE READER USE 2-PAGE VIEW (BOOK FORMAT WITH SCROLLING ENABLED) IN ACROBAT READER OR BROWSER. “EVEN’ING IT OUT – A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE LAST TWO YEARS OF “THE TWILIGHT ZONE” Television Series (minus ‘THE’)” A Study in Three Parts by Andrew Ramage © 2019, The Twilight Zone Museum. All rights reserved. Preface With some hesitation at CBS, Cayuga Productions continued Twilight Zone for what would be its last season, with a thirty-six episode pipeline – a larger count than had been seen since its first year. Producer Bert Granet, who began producing in the previous season, was soon replaced by William Froug as he moved on to other projects. The fifth season has always been considered the weakest and, as one reviewer stated, “undisputably the worst.” Harsh criticism. The lopsidedness of Seasons 4 and 5 – with a smattering of episodes that egregiously deviated from the TZ mold, made for a series much-changed from the one everyone had come to know. A possible reason for this was an abundance of rather disdainful or at least less-likeable characters. Most were simply too hard to warm up to, or at the very least, identify with. But it wasn’t just TZ that was changing. Television was no longer as new a medium. “It was a period of great ferment,” said George Clayton Johnson. By 1963, the idyllic world of the 1950s was disappearing by the day. More grittily realistic and reality-based TV shows were imminent, as per the viewing audience’s demand and it was only a matter of time before the curtain came down on the kinds of shows everyone grew to love in the 50s. -

Keith Resume

347-404-0422 Height: 5’ 11’’ [email protected] Weight: 185 lbs. bindlestiff.org Hair: Dk Brown, Long Keith Nelson Eyes: Brown VARIETY ENTERTAINER * J UGGLER * S IDESHOW MARVEL * C LOWN * M ASTER OF CEREMONIES PERFORMING PROFESSIONALLY SINCE 1994 Performance Skills Sideshow Feats: Circus Skills: Diabolo Bullwhip Sword Swallowing Clowning Balloon Sculpture Archery Fire-eating Stilt Walking Balancing Gun Spinning Bed of Nails Unicycling Mouth sticks Human Blockhead Basic Tumbling/Acrobatics Bottle and glass tricks Additional Skills Mental Floss Tuba Straight Jacket Escape Prop Manipulation: Western Skills: Concertina Juggling Trick Rope Spinning Magic Plate Spinning Knife Throwing Basic Tap Dancing Work Experience - Venues & Festivals Avery Fischer Hall (w/ Ornette Coleman), NYC King Opera House, Van Buren, AK Hall & Christ’s World of Wonders, NJ San Diego Street Scene, CA Yale Cabaret, Yale University, CT Blue Angel Cabaret, NY Toyota Comedy Festival, NY Knitting Factory, NY Burning Man Festival, NV Bonnaroo, TN Glastonbury Festival, UK All Good Festival, WV Coney Island Sideshow by the Seashore, NY MGM Grand Theater, Washington, DC Wild Style Tattoo Convention, Austria Borgata Hotel and Casino, Atlatnic City Television/Film/Video Late Late Show with James Corden “The Today Show,” NBC “On the Inside,” BBC Late Night w/ David Letterman,” CBS “Twisted Lives of Contortionist,” “Tudo de Bom,” MTV Brazil “Carson Daly Show,” NBC Discovery “Tonigh Show wih Jay Leno” “Oddville,” MTV “Rock of Ages,” VH-1 “OZ.” HBO “212,” FOX Clients Bendel’s -

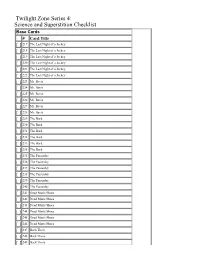

Twilight Zone Series 4: Science and Superstition Checklist

Twilight Zone Series 4: Science and Superstition Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 217 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 218 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 219 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 220 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 221 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 222 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 223 Mr. Bevis [ ] 224 Mr. Bevis [ ] 225 Mr. Bevis [ ] 226 Mr. Bevis [ ] 227 Mr. Bevis [ ] 228 Mr. Bevis [ ] 229 The Bard [ ] 230 The Bard [ ] 231 The Bard [ ] 232 The Bard [ ] 233 The Bard [ ] 234 The Bard [ ] 235 The Passersby [ ] 236 The Passersby [ ] 237 The Passersby [ ] 238 The Passersby [ ] 239 The Passersby [ ] 240 The Passersby [ ] 241 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 242 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 243 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 244 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 245 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 246 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 247 Back There [ ] 248 Back There [ ] 249 Back There [ ] 250 Back There [ ] 251 Back There [ ] 252 Back There [ ] 253 The Purple Testament [ ] 254 The Purple Testament [ ] 255 The Purple Testament [ ] 256 The Purple Testament [ ] 257 The Purple Testament [ ] 258 The Purple Testament [ ] 259 A Piano in the House [ ] 260 A Piano in the House [ ] 261 A Piano in the House [ ] 262 A Piano in the House [ ] 263 A Piano in the House [ ] 264 A Piano in the House [ ] 265 Night Call [ ] 266 Night Call [ ] 267 Night Call [ ] 268 Night Call [ ] 269 Night Call [ ] 270 Night Call [ ] 271 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 272 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 273 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 274 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 275 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 276 A Hundred