'An Internationalised Rupee?'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The World Bank IMPLEMENTATION COMPLETION and RESULTS

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Report No: ICR00004941 IMPLEMENTATION COMPLETION AND RESULTS REPORT IDA 47440 and 54310 (AF) ON A CREDIT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR7.75 MILLION (US$12.0 MILLION EQUIVALENT) AND AN ADDITIONAL CREDIT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR11.3 MILLION (US$17.4 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE KINGDOM OF BHUTAN FOR THE SECOND URBAN DEVELOPMENT PROJECT DECEMBER 27, 2019 Urban, Resilience And Land Global Practice Sustainable Development South Asia Region CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective November 27, 2019) Bhutanese Currency Unit = Ngultrum (BTN) BTN71.31 = US$1 US$1.37 = SDR 1 FISCAL YEAR July 1 - June 30 Regional Vice President: Hartwig Schafer Country Director: Mercy Miyang Tembon Regional Director: John A. Roome Practice Manager: Catalina Marulanda Task Team Leader(s): David Mason ICR Main Contributor: David Mason ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ADB Asian Development Bank AF Additional Financing AHP Affected Households and Persons APA Alternative Procurement Arrangement BLSS Bhutan Living Standards Survey BTN Bhutanese Ngultrum BUDP-1 Bhutan Urban Development Project (Cr. 3310) BUDP-2 Second Bhutan Urban Development Project CAS Country Assistance Strategy CNDP Comprehensive National Development Plan CPF Country Partnership Framework CPLC Cash Payment in Lieu of Land Compensation CWSS Central Water Supply Scheme DAR Digital Asset Registry EMP Environmental Management Plan FM Financial Management FYP Five Year Plan GNHC Gross National Happiness Commission GRC Grievance Redress Committee GRM Grievance Redressal Mechanism -

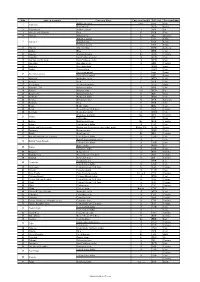

Country, Capital, Currency

List of all Countries, Capitals & Currencies of the World Country Capital Currency Afghanistan Kabul Afghan afghani Albania Tirana Albanian lek Algeria Agiers Algerian dinar Andorra Andorra la Vella Euro Angola Luanda Kwanza Antigua and Barbuda St. John’s East Caribbean dollar Argentina Buenos Aires Argentine peso Armenia Yerevan Armenian dram Australia Canberra Australian dollar Austria Vienna Euro Azerbaijan Baku Azerbaijani manat Bahamas Nassau Bahamian dollar Bahrain Manama Bahraini dinar Bangladesh Dhaka Bangladeshi taka Barbados Bridgetown Barbadian dollar Belarus Minsk Belarusian ruble Belgium Brussels Euro Belize Belmopan Belize dollar Benin Porto-Novo (official) West African CFA franc Bhutan Thimpu Bhutanese ngultrum Bolivia Sucre Bolivian boliviano Bosnia and Herzegovina Sarajevo Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark Botswana Gaborone Pula Brazil Brasília Brazilian real Brunei Bandar Seri Begawan Brunei dollar Bulgaria Sofia Bulgarian lev Burkina Faso Ouagadougou West African CFA franc Burundi Bujumbura Burundian franc Cambodia Phnom Penh Cambodian riel Cameroon Yaoundé Central African CFA franc Canada Ottawa Canadian dollar Cape Verde Praia Cape Verdean escudo Central African Republic Bangui Central African CFA franc Chad N’Djamena Central African CFA franc Chile Santiago Chilean peso China Beijing Chinese Yuan Renminbi Colombia Bogotá Colombian peso Comoros Moroni Comorian franc Costa Rica San José Costa Rican colon Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast) Yamoussoukro (official),Abidjan West African CFA franc (seat of government) Croatia -

Exchange Rate Statistics

Exchange rate statistics Updated issue Statistical Series Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics 2 This Statistical Series is released once a month and pub- Deutsche Bundesbank lished on the basis of Section 18 of the Bundesbank Act Wilhelm-Epstein-Straße 14 (Gesetz über die Deutsche Bundesbank). 60431 Frankfurt am Main Germany To be informed when new issues of this Statistical Series are published, subscribe to the newsletter at: Postfach 10 06 02 www.bundesbank.de/statistik-newsletter_en 60006 Frankfurt am Main Germany Compared with the regular issue, which you may subscribe to as a newsletter, this issue contains data, which have Tel.: +49 (0)69 9566 3512 been updated in the meantime. Email: www.bundesbank.de/contact Up-to-date information and time series are also available Information pursuant to Section 5 of the German Tele- online at: media Act (Telemediengesetz) can be found at: www.bundesbank.de/content/821976 www.bundesbank.de/imprint www.bundesbank.de/timeseries Reproduction permitted only if source is stated. Further statistics compiled by the Deutsche Bundesbank can also be accessed at the Bundesbank web pages. ISSN 2699–9188 A publication schedule for selected statistics can be viewed Please consult the relevant table for the date of the last on the following page: update. www.bundesbank.de/statisticalcalender Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics 3 Contents I. Euro area and exchange rate stability convergence criterion 1. Euro area countries and irrevoc able euro conversion rates in the third stage of Economic and Monetary Union .................................................................. 7 2. Central rates and intervention rates in Exchange Rate Mechanism II ............................... 7 II. -

The Rupee Crunch and India-Bhutan Economic Engagement 2

IDSA Issue Brief IDSIDSAA ISSUEISSUE BRIEFBRIEF1 The Rupee Crunch and India- Bhutan Economic Engagement* Medha Bisht Dr Medha Bisht is Associate Fellow at the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi July 16, 2012 Summary The rupee-crunch in Bhutan may be a purely domestic issue occasioned by poor fiscal policies and mismanagement of economic affairs. However, there is a strong view gaining ground among the Bhutanese that it is primarily caused by their economic dependence on India, sustained by growing economic ties between the two countries. It is, therefore, important to understand the geographical constraints, the limits of the political economy in Bhutan, and the causes of growing Bhutanese disillusionment about ties with India. While it would be an overstatement to say that such crises could significantly impact India-Bhutan relations, it nevertheless shows that the rupee crunch is an important pointer to the fact that Bhutan's business sector is feeling squeezed by some of the economic policies being pursued by the Indian government. While loans, grants and lines of credit offer a solution to deal with immediate crises, it is important to gauge the long-term impact of such Indian policies on bilateral relations. * The author undertook a field visit to Thimpu, Bhutan in May 2012 and interacted with a cross section of analysts and academics. The author thanks the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses for providing financial support to undertake the visit as well as the various individuals in Bhutan who graciously met with her and willingly shared their ideas and opinions. Disclaimer: Views expressed in IDSA’s publications and on its website are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IDSA or the Government of India. -

Country Scheme Alpha 3 Alpha 2 Currency Albania MC / VI ALB AL

Country Scheme Alpha 3 Alpha 2 Currency Albania MC / VI ALB AL Lek Algeria MC / VI DZA DZ Algerian dinar Argentina MC / VI ARG AR Argentine peso Australia MC / VI AUS AU Australian dollar -Christmas Is. -Cocos (Keeling) Is. -Heard and McDonald Is. -Kiribati -Nauru -Norfolk Is. -Tuvalu Christmas Island MC CXR CX Australian dollar Cocos (Keeling) Islands MC CCK CC Australian dollar Heard and McDonald Islands MC HMD HM Australian dollar Kiribati MC KIR KI Australian dollar Nauru MC NRU NR Australian dollar Norfolk Island MC NFK NF Australian dollar Tuvalu MC TUV TV Australian dollar Bahamas MC / VI BHS BS Bahamian dollar Bahrain MC / VI BHR BH Bahraini dinar Bangladesh MC / VI BGD BD Taka Armenia VI ARM AM Armenian Dram Barbados MC / VI BRB BB Barbados dollar Bermuda MC / VI BMU BM Bermudian dollar Bolivia, MC / VI BOL BO Boliviano Plurinational State of Botswana MC / VI BWA BW Pula Belize MC / VI BLZ BZ Belize dollar Solomon Islands MC / VI SLB SB Solomon Islands dollar Brunei Darussalam MC / VI BRN BN Brunei dollar Myanmar MC / VI MMR MM Myanmar kyat (effective 1 November 2012) Burundi MC / VI BDI BI Burundi franc Cambodia MC / VI KHM KH Riel Canada MC / VI CAN CA Canadian dollar Cape Verde MC / VI CPV CV Cape Verde escudo Cayman Islands MC / VI CYM KY Cayman Islands dollar Sri Lanka MC / VI LKA LK Sri Lanka rupee Chile MC / VI CHL CL Chilean peso China VI CHN CN Colombia MC / VI COL CO Colombian peso Comoros MC / VI COM KM Comoro franc Costa Rica MC / VI CRI CR Costa Rican colony Croatia MC / VI HRV HR Kuna Cuba VI Czech Republic MC / VI CZE CZ Koruna Denmark MC / VI DNK DK Danish krone Faeroe Is. -

India-Persian Gulf Relations: from Transactional to Strategic Partnerships

India-Persian Gulf Relations: From Transactional to Strategic Partnerships D WA Manjari Singh LAN RFA OR RE F S E T R U T D India’s relationsN with the Gulf countries have been exceptionallyIE significant since ancientE times and are multifaceted. The two have maintainedS C historical ties with each other in terms of trade, energy, security as well as a vast expatriate population. While the Indo-Gulf relations are dominated by energy cooperation, recent years have experienced a shift in their dynamics. Owing to Persian Gulf countries’ quest to achieve Vision 2030 through economic diversification, Indo-Gulf relations have seen an expansion in other non-conventional areas such as security cooperation and strategic partnerships. India is not in military alliance with any of the major powers, however, it sharesCLAWS close strategic and military relations with many majorV countries in the world. Owing to growing stature of IC ON India and its clout atT Othe global table, India startedISI to build strategic RY H V partnerships with major countries TH RsuchOU asG France, Russia, Germany, and the US, etc., since 1997.1 It is noteworthy that India has extended its strategic partnerships with as many as four countries in the Gulf, namely, Iran, Oman, Saudi Arabia, the UAE since 2003.2 This shows that over a period of time the region holds immense significance for India’s ascendance as a growing regional and global power. Dr. Manjari Singh is an Associate Fellow at Centre for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS), New Delhi and also serves as the Managing Editor of CLAWS Journal, Summer Issue 2020. -

CURRENCY BOARD FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Currency Board Working Paper

SAE./No.22/December 2014 Studies in Applied Economics CURRENCY BOARD FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Currency Board Working Paper Nicholas Krus and Kurt Schuler Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and Study of Business Enterprise & Center for Financial Stability Currency Board Financial Statements First version, December 2014 By Nicholas Krus and Kurt Schuler Paper and accompanying spreadsheets copyright 2014 by Nicholas Krus and Kurt Schuler. All rights reserved. Spreadsheets previously issued by other researchers are used by permission. About the series The Studies in Applied Economics of the Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health and the Study of Business Enterprise are under the general direction of Professor Steve H. Hanke, co-director of the Institute ([email protected]). This study is one in a series on currency boards for the Institute’s Currency Board Project. The series will fill gaps in the history, statistics, and scholarship of currency boards. This study is issued jointly with the Center for Financial Stability. The main summary data series will eventually be available in the Center’s Historical Financial Statistics data set. About the authors Nicholas Krus ([email protected]) is an Associate Analyst at Warner Music Group in New York. He has a bachelor’s degree in economics from The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, where he also worked as a research assistant at the Institute for Applied Economics and the Study of Business Enterprise and did most of his research for this paper. Kurt Schuler ([email protected]) is Senior Fellow in Financial History at the Center for Financial Stability in New York. -

Twelfth Session, Commencing at 11.30 Am INDIAN COINS

Twelfth Session, Commencing at 11.30 am INDIAN COINS 3123 Ancient India, punched marked coinage, Magadha, Mauryan and other Empires, (400-100 B.C.), punch marked mostly square/rectangular shaped issues some round, silver karshapana, usually with set of fi ve punch marked symbols on the obverse, many with additional marks on the reverse. 3127* Very good - fi ne. (7) India, Bengal Presidency, EIC rupee, Farrukhabad mint year $100 45, (1820-1830), straight grained edge (KM.70); another Ex Jonathan Cohen Collection. rupee, year 45 (1820), plain edge, (KM.78). Extremely fi ne. (2) $100 3128 India, Bengal Presidency, EIC rupee, Farrukhabad mint year 45, (1820-1830), straight grained edge (KM.70); another rupee, year 45 (1820), plain edge, (KM.78). Extremely fi ne. (2) $100 3124* India, Native States, Bundi, silver rupee (VS 1921), 1864; half rupee (VS 1905), 1848 (KM.5,6). Nearly extremely fi ne; nearly very fi ne (the date unpublished). (2) $150 Ex Ken O'Brien Collection, Noble Numismatics Sale 46 (lot 2314) and Gray Donaldson Collection. part 3129* India, Bengal Presidency, Indian Design, Murshidabad (Calcutta) Mint, 1791-1793, Perpetual 19 san sicca series, Standard Silver Currency, in the name of Shah Alam II (A.H. 1173-1221, A.D.1759-1806), machine made silver rupee, Regnal year 19 (fi xed), with date off fl an, Privy mark crescent under Shah Alam, (KM.86) (illustrated); silver rupees, 3125* Banares mint (3), 1196, regal year 17/24 (1781-2); 1197, India, Punjab, Sikh Empire, Ranjit Singh, (VS 1856-1896, regal year 17/25 (1782-3); 1202, regal year 17/29 (1787-8); A.D. -

Financial Planner – Bhutan

BHUTAN FINANCIAL PLANNING GUIDE HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE This document is meant to help you plan financially for studying abroad. Study abroad is an investment in yourself - you’ll return home with new experiences, skills, knowledge, and friendships that will stay with you for the rest of your life. As with any investment, there are costs involved, which are best managed through proper planning and awareness. We hope this financial planner will help you prepare for your study abroad experience and get as much out of it as possible. Start with the list below - this is an overview of what’s included in the standard program cost. Next, refer to the chart further down this page for a breakdown of basic expenses like tuition, room and board, as well as some additional estimated expenses that are either required or likely to be incurred. Head to the second page of the guide for more detailed tips and information on managing your finances while in the field, and our billing policy. Finally, the third page includes information on financial aid and scholarships. WHAT’S INCLUDED IN THE COST OF AN SFS PROGRAM? • Pre-program advising • Daily meals and snacks • Field excursions & cultural activities • On-site orientation • Housing (field station and on excursions) • Emergency evacuation & 24/7 support • Tuition and research fees • Airport transfers (for arrival/departure) • Official transcript processing COST BREAKDOWN BASIC COSTS (BILLED BY SFS) SEMESTER SUMMER I SUMMER II SUMMER COMBINED Fa ‘21 - Sp ‘22 Su ‘22 Su ‘22 Tuition $18,325 $4,950 $4,950 $9,900 Room & Board $7,625 $2,150 $2,150 $4,300 BASIC PROGRAM COST $25,950 $7,100 $7,100 $13,200* ADDITIONAL COSTS (ESTIMATED) - The following should be used for planning purposes only; actual expenses may vary. -

List of Currencies of All Countries

The CSS Point List Of Currencies Of All Countries Country Currency ISO-4217 A Afghanistan Afghan afghani AFN Albania Albanian lek ALL Algeria Algerian dinar DZD Andorra European euro EUR Angola Angolan kwanza AOA Anguilla East Caribbean dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar XCD Argentina Argentine peso ARS Armenia Armenian dram AMD Aruba Aruban florin AWG Australia Australian dollar AUD Austria European euro EUR Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat AZN B Bahamas Bahamian dollar BSD Bahrain Bahraini dinar BHD Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka BDT Barbados Barbadian dollar BBD Belarus Belarusian ruble BYR Belgium European euro EUR Belize Belize dollar BZD Benin West African CFA franc XOF Bhutan Bhutanese ngultrum BTN Bolivia Bolivian boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina konvertibilna marka BAM Botswana Botswana pula BWP 1 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Brazil Brazilian real BRL Brunei Brunei dollar BND Bulgaria Bulgarian lev BGN Burkina Faso West African CFA franc XOF Burundi Burundi franc BIF C Cambodia Cambodian riel KHR Cameroon Central African CFA franc XAF Canada Canadian dollar CAD Cape Verde Cape Verdean escudo CVE Cayman Islands Cayman Islands dollar KYD Central African Republic Central African CFA franc XAF Chad Central African CFA franc XAF Chile Chilean peso CLP China Chinese renminbi CNY Colombia Colombian peso COP Comoros Comorian franc KMF Congo Central African CFA franc XAF Congo, Democratic Republic Congolese franc CDF Costa Rica Costa Rican colon CRC Côte d'Ivoire West African CFA franc XOF Croatia Croatian kuna HRK Cuba Cuban peso CUC Cyprus European euro EUR Czech Republic Czech koruna CZK D Denmark Danish krone DKK Djibouti Djiboutian franc DJF Dominica East Caribbean dollar XCD 2 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Dominican Republic Dominican peso DOP E East Timor uses the U.S. -

Foreign Exchange Regulations.Pdf

THE KINGDOM OF BHUTAN FOREIGN EXCHANGE REGULATIONS, 2013 THE FOREIGN EXCHANGE REGULATIONS, 2013 ........................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER I: PRELIMINARY .................................................................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER II: IMPORT AND EXPORT OF CURRENCY, GOLD, AND SILVER........................................... 1 CHAPTER III A: AUTHORIZATION TO DEAL IN FOREIGN EXCHANGE ................................................. 3 CHAPTER III B: FOREIGN EXCHANGE TRANSACTIONS, EXCHANGE RATES, AND FOREIGN EXCHANGE HOLDINGS OF AUTHORIZED BANKS ........................................................................................ 3 CHAPTER III C: FOREIGN EXCHANGE TRANSACTIONS, EXCHANGE RATES, AND FOREIGN EXCHANGE HOLDINGS OF AUTHORIZED MONEY CHANGERS ............................................................... 4 CHAPTER IV: INTERNATIONAL MONEY TRANSFER SERVICES ............................................................. 6 CHAPTER V: PAYMENT ARRANGEMENTS ................................................................................................. 7 CHAPTER VI: CURRENT TRANSACTIONS ....................................................................................................... 8 CHAPTER VII: CAPITAL TRANSACTIONS ..................................................................................................... 14 CHAPTER VIII: BANK ACCOUNTS IN BHUTAN AND ABROAD ............................................................... -

S.No State Or Territory Currency Name Currency Symbol ISO Code

S.No State or territory Currency Name Currency Symbol ISO code Fractional unit Abkhazian apsar none none none 1 Abkhazia Russian ruble RUB Kopek Afghanistan Afghan afghani ؋ AFN Pul 2 3 Akrotiri and Dhekelia Euro € EUR Cent 4 Albania Albanian lek L ALL Qindarkë Alderney pound £ none Penny 5 Alderney British pound £ GBP Penny Guernsey pound £ GGP Penny DZD Santeem ﺩ.ﺝ Algeria Algerian dinar 6 7 Andorra Euro € EUR Cent 8 Angola Angolan kwanza Kz AOA Cêntimo 9 Anguilla East Caribbean dollar $ XCD Cent 10 Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar $ XCD Cent 11 Argentina Argentine peso $ ARS Centavo 12 Armenia Armenian dram AMD Luma 13 Aruba Aruban florin ƒ AWG Cent Ascension pound £ none Penny 14 Ascension Island Saint Helena pound £ SHP Penny 15 Australia Australian dollar $ AUD Cent 16 Austria Euro € EUR Cent 17 Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat AZN Qəpik 18 Bahamas, The Bahamian dollar $ BSD Cent BHD Fils ﺩ.ﺏ. Bahrain Bahraini dinar 19 20 Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka ৳ BDT Paisa 21 Barbados Barbadian dollar $ BBD Cent 22 Belarus Belarusian ruble Br BYR Kapyeyka 23 Belgium Euro € EUR Cent 24 Belize Belize dollar $ BZD Cent 25 Benin West African CFA franc Fr XOF Centime 26 Bermuda Bermudian dollar $ BMD Cent Bhutanese ngultrum Nu. BTN Chetrum 27 Bhutan Indian rupee ₹ INR Paisa 28 Bolivia Bolivian boliviano Bs. BOB Centavo 29 Bonaire United States dollar $ USD Cent 30 Bosnia and Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark KM or КМ BAM Fening 31 Botswana Botswana pula P BWP Thebe 32 Brazil Brazilian real R$ BRL Centavo 33 British Indian Ocean