THE MATANUSKA VALLEY Colony ■»

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Field-Trip Guide to Volcanic and Volcaniclastic Deposits of the Lower Jurassic Talkeetna Formation, Sheep Mountain, South-Central Alaska

Field-Trip Guide to Volcanic and Volcaniclastic Deposits of the Lower Jurassic Talkeetna Formation, Sheep Mountain, South-Central Alaska U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2006-1124 Field-Trip Guide to Volcanic and Volcaniclastic Deposits of the Lower Jurassic Talkeetna Formation, Sheep Mountain, South-Central Alaska Amy E. Draut U.S. Geological Survey, Pacific Science Center, Santa Cruz, CA 95060 Peter D. Clift School of Geosciences, University of Aberdeen, AB24 3UE, U.K. Robert B. Blodgett U.S. Geological Survey–Contractor, Anchorage, AK 99508 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Open-File Report 2006-1124 2006 U.S. Department of the Interior P. Lynn Scarlett, Acting Secretary U.S. Geological Survey P. Patrick Leahy, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia 2006 Revised and reprinted: 2006 Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government To download a copy of this report from the World Wide Web: http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2006/1124/ For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted material contained within this report. LIST OF FIGURES FIGURE 1. Regional map of the field-trip area. FIGURE 2. Geologic cross section through Sheep Mountain. FIGURE 3. Stratigraphic sections on the south side of Sheep Mountain. -

Human Services Coordinated Transportation Plan for the Mat-Su Borough Area

Human Services Coordinated Transportation Plan For the Mat-Su Borough Area Phase III – 2011-2016 Final Draft January 2011 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 3 Community Background .................................................................................................. 4 Coordinated Services Element ........................................................................................ 6 Coordination Working Group – Members (Table I) ................................................... 6 Inventory of Available Resources and Services (Description of Current Service / Public Transportation) .............................................................................................. 7 Description of Current Service / Other Transportation (Table II) .............................. 8 Assessment of Available Services – Public Transportation (Table III) ................... 13 Human Services Transportation Community Client Referral Form......................... 16 Population of Service Area: .................................................................................... 16 Annual Trip Destination Distribution – Current Service: ......................................... 19 Annual Trip Destination Distribution (Table V) ....................................................... 19 Vehicle Inventory .................................................................................................... 20 Needs Assessment ...................................................................................................... -

Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) for Residue Adjacent to the Waters of the Matanuska River in Palmer, Alaska Public Notice Draft

Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation 555 Cordova Street Anchorage, Alaska 99501 Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) for Residue Adjacent to the Waters of the Matanuska River in Palmer, Alaska Public Notice Draft July 2017 Draft TMDL for Residue Adjacent to the Matanuska River, AK July 2017 Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................... 7 1 Overview ..................................................................................................................................................... 9 1.1 Location of TMDL Study Area ....................................................................................................... 9 1.2 Population ........................................................................................................................................ 13 1.3 Topography ...................................................................................................................................... 13 1.4 Land Use and Land Cover ............................................................................................................. 13 1.5 Soils and Geology ............................................................................................................................ 14 1.6 Climate .............................................................................................................................................. 17 1.7 Hydrology and Waterbody -

The Little Susitna River— an Ecological Assessment

The Little Susitna River— An Ecological Assessment Jeffrey C. Davis and Gay A. Davis P.O. Box 923 Talkeetna, Alaska (907) 733.5432. www.arrialaska.org July 2007 Acknowledgements This project was completed with support from the State of Alaska, Alaska Clean Water Action Plan program, ACWA 07-11. Laura Eldred, the DEC Project Manger provided support through comments and suggestion on the project sampling plan, QAPP and final report. Nick Ettema from Grand Valley State University assisted in data collection. ARRI—Little Susitna River July 2007 Table of Contents Summary............................................................................................................................. 2 Introduction......................................................................................................................... 3 Methods............................................................................................................................... 4 Sampling Locations ........................................................................................................ 4 Results................................................................................................................................. 6 Riparian Development .................................................................................................... 6 Index of Bank Stability ................................................................................................... 7 Chemical Characteristics and Turbidity......................................................................... -

The Climate of the Matanuska Valley

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE SINCLAIR WEEKS, Secretary WEATHER BUREAU F. W. REICHELDERFER, Chief TECHNICAL PAPER NO. 27 The Climate of the Matanuska Valley Prepared by ROBERT F. DALE CLIMATOLOGICAL SECTION CENTER. U. S. WEATHER BUREAU, ANCHORAGE, ALASKA WASHINGTON, D. C. MARCH 1956 For sale by the Superintendent of Document!!, U. S. Government Printing Office, Washington 25, D. C. • Price 25 cents PREFACE This study was made possible only through the unselfish service of the copperative weather observers listed in table 1 and the Weather Bureau and Soil Conservation officials who conceived and implemented the network in 1941. Special mention should be given Max Sherrod at Matanuska No. 12, and Irving Newville (deceased) at Matanuska No. 2, both original colonists and charter observers with more than 10 years of cooperative weather observing to their credit. Among the many individuals who have furnished information and assistance in the preparation of this study should be mentioned Don L. Irwin Director of the Alaska Agricultural Experiment Station; Dr. Curtis H. Dear born, Horticulturist and present weather observer at the Matanuska Agri cultural Experiment Station; Glen Jefferson, Regional Director, and Mac A. Emerson, Assistant Regional Director, U. S. Weather Bureau; and Alvida H. Nordling, my assistant in the Anchorage Climatological Section. RoBERT F. DALE. FEBRUARY 1955. III CONTENTS Page Preface____________________________________________________________________ III 1. Introduction____________________________________________________________ -

A Comprehensive Inventory of Impaired Anadromous Fish Habitats in the Matanuska-Susitna Basin, with Recommendations for Restoration, 2013 Prepared By

A Comprehensive Inventory of Impaired Anadromous Fish Habitats in the Matanuska-Susitna Basin, with Recommendations for Restoration, 2013 Prepared by ADF&G Habitat Research and Restoration Staff – October 2013 Primary contact: Dean W. Hughes (907) 267-2207 Abstract This document was written to identify the factors or activities that are likely to negatively impact the production of salmonids in the Matanuska-Susitna (Mat-Su) basin and to offer mitigation measures to lessen those impacts. Potential impacts can be characterized in two different catagories; natural and anthropogenic. Natural threats to salmon habitat in the Mat-Su basin include natural loss or alteration of wetland and riparian habitats, alteration of water quality and quantity, and beaver dams blocking fish migration. Anthropogenic impacts include urbanization that increases loss or alteration of wetlands and riparian habitats and decreases water quantity and quality; culverts that block or impair fish passage; ATV impacts to spawning habitats, stream channels, wetlands and riparian habitats; “coffee can” introduction of pike in salmon waters; and, beaver dams at or in culverts. What resulted is an amalgamation of existing research and expertise delivered in a brief narrative describing those limiting factors and activities, as well as an appendix listing possible studies to better understand those impacts and potential projects to limit or repair damage to important salmon habitats (Appendix A). Introduction The Matanuska-Susitna (Mat-Su) Basin is drained primarily by two major rivers, the Matanuska and Susitna. The Susitna River watershed encompasses 19,300 square miles, flowing over 300 miles from the Susitna Glacier in the Alaska Range, through the Talkeetna Mountains, to upper Cook Inlet. -

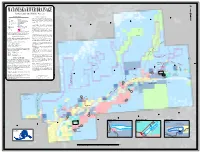

Matanuska Valley Moose Range Land Status

149°24'0"W 149°15'0"W 149°6'0"W 148°57'0"W 148°48'0"W 148°39'0"W 148°30'0"W 148°21'0"W 148°12'0"W 148°3'0"W MATANUSKA RIVER DRAINAGE N Land Status and Public Access " 0 ' 0 ° 2 L a n d S t a t u s 6 PUBLIC USE EASEMENTS S t a t e P r i v a t e Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act 17(b) easements exist to provide access across privately owned lands to reach General Cook Inlet Region Inc. public lands or major waterways. No hunting or fishing from School Trust Chickaloon Moose Creek or on an easement is permitted. No camping is allowed on Native Assoc. Inc. trail easements. Mental Health Trust Eklutna Inc. Other There are two types of 17(b) easements: site easements Other and trail easements. There are no site easements reserved M u n i c i p a l P u b l i c T r a i l s a n d in this area. The following trail easements were reserved across corporation lands. Municipal R i g h t s - o f - W a y t h i s m a p d o e s n o t s h o w a l l t r a i l s F e d e r a l EIN 1a D9 – An easement, twenty-five (25) feet in width, for R N DOT an existing access trail beginning in Sec. -

Alaska Natives

DOCUMENT RESUME- ED 376 005 RC 019 845 AUTHOR Chandonnet, Ann TITLE Chief Stephen's Parky: One Year in the Life of an Athapascan Girl. The Council for Indian Education Series. REPORT NO ISBN-1-879373-39-4 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 95p.; Photographs and illustrations may not reproduce clearly. AVAILABLE FWM Roberts Rinehart Publishers, P.O. Box 666, Niwot, CO 80544 (ISBN-1-879373-39-4, $7.95). PUB TYPE Books (010) Guides Classroom Use Instructional Materials (For Learner) (051) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adolescent Literature; *Alaska Natives; *American Indian Culture; American Indian History; American Indians; *Clothing; Elementa'ry Secondary Education; *Family Life; *Females; Fiction; Migration; *Sex Role IDENTIFIERS *Athapascan (Tribe); Trapping ABSTRACT This book tells the fictional story of Olga, the wife of Chief Stephen, leader of a Tanaina Athapascan village on Cook Inlet, northwest of Anchorage, Alaska. Olga works for one full year with great courage and independence trapping ground squirrels and gathering materials needed to tan, dye, and sew furs to make a parka for her husband. She uses alder bark for dye, whale sinew for thread, sealskin for trim, a tough piece of hide for a thimble, a sharpened ground-squirrel leg bone for a needle, and an awl made from moose antler with a handle of moose bone. With these materials, she makes her husband, Chief Stephen, the most beautiful, functional, and creative squirrel skin parka the village has ever seen. The warm clothing Olga provides for the chief makes possible his success as a hunter, trapper, and village leader. Like other Athapascans, the Tanaina were hunter-gatherers and led a nomadic life style. -

Copper River Native Places River Native Copper Mission Statement

U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management BLM Alaska Technical Report 56 BLM/AK/ST-05/023+8100+050 December 2005 Copper River Native Places A report on culturally important places to Alaska Native tribes in Southcentral Alaska Dr. James Kari and Dr. Siri Tuttle Alaska U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMMENT Mission Statement The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) sustains the health, diversity and productivity of the public lands for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations. Author Dr. James Kari is a professor emeritus of The Alaska Native Language Center, Fairbanks. Siri Tuttle is an Assistant Professor of Linguistics at The Alaska Native Language Center, Fairbanks. Cover Ahtna caribou hunting camp on the Delta River in 1898. From Mendenhall 1900: Plate XXI-A. Technical Reports Technical Reports issued by the Bureau of Land Management-Alaska present the results of research, studies, investigations, literature searches, testing, are similar endeavors on a variety of scientific and technical subjects. The results presented are final, or a summation and analysis of data at an intermedi- ate point in a long-term research project and have received objective review by peers in the authorʼs field. Reports are available while supplies last from BLM External Affairs, 222 West 7th Avenue, #13, Anchorage, Alaska 99513 (907) 271-5555 and from the Juneau Minerals Information Center, 100 Savikko Road, Mayflower Island, Douglas, AK 99824, (907) 364-1553. Copies are also available for inspection at the Alaska Resource Library and Information Service (Anchorage), the United States Department of the Interior Resources Library in Washington D.C., various libraries of the University of Alaska, the BLM National Business Center Library (Denver), and other selected locations. -

Stratigraphic and Geochemical Evolution of an Oceanic Arc Upper Crustal Section: the Jurassic Talkeetna Volcanic Formation, South-Central Alaska

Stratigraphic and geochemical evolution of an oceanic arc upper crustal section: The Jurassic Talkeetna Volcanic Formation, south-central Alaska Peter D. Clift† Department of Geology and Petroleum Geology, University of Aberdeen, Meston Building, Aberdeen AB24 3UE, UK Amy E. Draut U.S. Geological Survey, 400 Natural Bridges Drive, Santa Cruz, California 95060, USA and Department of Earth Sciences, University of California, 1156 High Street, Santa Cruz, California 95064, USA Peter B. Kelemen Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, P.O. Box 1000, 61 Route 9W, Palisades, New York 10964, USA Jerzy Blusztajn Department of Geology and Geophysics, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, Massachusetts 02543, USA Andrew Greene Department of Geology, Western Washington University, Bellingham, Washington 98225, USA ABSTRACT is typically more REE depleted than average continental margins (e.g., Petterson et al., 1993; continental crust, although small volumes of Draut and Clift, 2001; Draut et al., 2002). Others The Early Jurassic Talkeetna Volcanic light REE-enriched and heavy REE-depleted propose that some arcs are andesitic rather than Formation forms the upper stratigraphic level mafi c lavas are recognized low in the stratig- basaltic and that the proportion of andesitic arcs of an oceanic volcanic arc complex within the raphy. The Talkeetna Volcanic Formation was may have been greater in the past (e.g., Taylor, Peninsular Terrane of south-central Alaska. formed in an intraoceanic arc above a north- 1967; Martin, 1986; Kelemen et al., 1993, 2003). The section comprises a series of lavas, tuffs, dipping subduction zone and contains no pre- Finally, others emphasize that continental crust and volcaniclastic debris-fl ow and turbidite served record of its subsequent collisions with may be created by intracrustal differentiation of deposits, showing signifi cant lateral facies Wrangellia or North America. -

Matanuska River Watershed Plan

1 Matanuska River Watershed Plan Prepared by: U.S. Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service Palmer Field Office 1700 E. Bogard, Suite 203 Wasilla, AK 99654 JUNE 2006 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Approval of the Plan Acknowledgements Planning Signatures and Initiating Government Letters of Approval TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.0 INTRODUCTION AND PLANNING FRAMEWORK 1.1 Background and historical information 1.2 Studies and Reports: past and present 1.3 Purpose of the Plan 1.4 Limitations 2.0 WATERSHED CHARACTERIZATION 2.1 Natural Environment 2.1.1 Geography & Climate 2.1.2 Soils 2.1.3 Hydrology and Geohydrology 2.1.4 Biology 2.2 Human Environment 2.2.1 Land Use and Demographics 2.3 Tributaries 2.3.1 Overview 2.4 Water Resources 2.4.1 Water Quality 2.4.2 Water Quantity 3.0 RESOURCE CONCERNS 3.1 Critical Residential Area of concern 3.2 Habitat Conditions 4.0 IMPLEMENTATION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 4.1 Structural 4.2 Non-structural 5.0 COST BENEFIT COMPARISON 6.0 APPENDICES (Figures & Tables) 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The planning team consisted of NRCS staff with input from the Matanuska River Watershed Coalition group. The planning effort is the result of over ten years of ongoing erosion impacted-structures and public pressure to address the loss property. The following people participated in the Watershed Planning process. Initiating Governments Matanuska Susitna Borough (MSB) NRCS Watershed Coalition Team Author: Michelle Schuman, USDA, Natural Resources Conservation Service, District Conservationist, Palmer Field Office Review: -

Matanuska-Susitna Basin Salmon Habitat Partnership

Matanuska-Susitna Basin Salmon Habitat Partnership Healthy Salmon Healthy Communities The Matanuska-Susitna Basin Salmon Habitat Partnership believes that thriving fish, healthy habitats, and vital communities can co-exist in the Mat-Su Basin. Because wild salmon are central to life in Alaska, the partnership works to ensure quality salmon habitat is safeguarded and restored. This approach relies on collaboration and cooperation to get results. We live with salmon In the Matanuska-Susitna Basin, the magnitude of the landscape is matched only by the riches of its salmon streams. Each summer, millions of salmon return to the mighty Matanuska and Susitna rivers and the vast web of lakes and tributaries of the landscape we call home: The Mat-Su Basin. Those of us who live here know it is a spectacular place. It is an incredibly “People come up to the Mat-Su and diverse landscape – beyond our shopping centers and neighborhoods lie the forests of go fishing but that’s not the end of birch and spruce and expanses of tundra that ultimately rise up to the snowy elevations of the vacation. They’re going to stay in the area and do other things, too, so Denali, the Great One. there are spin-off effects on the local Five species of salmon – Chinook, coho, sockeye, pink and chum – surge up the economy.” waters of the Mat-Su each year. In the Susitna River drainage, 100,000-200,000 king salmon return each year, making it Alaska’s fourth-largest king salmon fishery – among – Mat-Su Salmon Partnership member the largest in the world.