Wallum and Related Vegetation on the NSW North Coast: Description and Phytosociological Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brooklyn, Cloudland, Melsonby (Gaarraay)

BUSH BLITZ SPECIES DISCOVERY PROGRAM Brooklyn, Cloudland, Melsonby (Gaarraay) Nature Refuges Eubenangee Swamp, Hann Tableland, Melsonby (Gaarraay) National Parks Upper Bridge Creek Queensland 29 April–27 May · 26–27 July 2010 Australian Biological Resources Study What is Contents Bush Blitz? Bush Blitz is a four-year, What is Bush Blitz? 2 multi-million dollar Abbreviations 2 partnership between the Summary 3 Australian Government, Introduction 4 BHP Billiton and Earthwatch Reserves Overview 6 Australia to document plants Methods 11 and animals in selected properties across Australia’s Results 14 National Reserve System. Discussion 17 Appendix A: Species Lists 31 Fauna 32 This innovative partnership Vertebrates 32 harnesses the expertise of many Invertebrates 50 of Australia’s top scientists from Flora 62 museums, herbaria, universities, Appendix B: Threatened Species 107 and other institutions and Fauna 108 organisations across the country. Flora 111 Appendix C: Exotic and Pest Species 113 Fauna 114 Flora 115 Glossary 119 Abbreviations ANHAT Australian Natural Heritage Assessment Tool EPBC Act Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Commonwealth) NCA Nature Conservation Act 1992 (Queensland) NRS National Reserve System 2 Bush Blitz survey report Summary A Bush Blitz survey was conducted in the Cape Exotic vertebrate pests were not a focus York Peninsula, Einasleigh Uplands and Wet of this Bush Blitz, however the Cane Toad Tropics bioregions of Queensland during April, (Rhinella marina) was recorded in both Cloudland May and July 2010. Results include 1,186 species Nature Refuge and Hann Tableland National added to those known across the reserves. Of Park. Only one exotic invertebrate species was these, 36 are putative species new to science, recorded, the Spiked Awlsnail (Allopeas clavulinus) including 24 species of true bug, 9 species of in Cloudland Nature Refuge. -

Australian Native Plants Society Canberra Region(Inc)

AUSTRALIAN NATIVE PLANTS SOCIETY CANBERRA REGION (INC) Journal Vol. 17 No. 4 December 2012 ISSN 1447-1507 Print Post Approved PP299436/00143 Contents ANPS Canberra Region Report 1 Whose Bean genus is that? 3 Winter Walks 6 Signs renewal for Frost Hollow to Forest Walk 16 Touga Road Touring 21 Study Group Snippets 25 Acacia Study Group Field Trip 27 ANPSA Study Groups 34 ANPS contacts and membership details inside back cover Cover: Correa reflexa, Kambah Pool, North; Photo: Martin Butterfield Journal articles The deadline dates for submissions are 1 February The Journal is a forum for the exchange of members' (March), 1 May (June), 1 August (September) and and others' views and experiences of gardening with, 1 November (December). Send articles or photos to: propagating and conserving Australian plants. Journal Editor All contributions, however short, are welcome. Gail Ritchie Knight Contributions may be typed or handwritten, and 1612 Sutton Road accompanied by photographs and drawings. Sutton NSW 2620 e-mail: [email protected] Submit photographs as either electronic files, tel: 0416 097 500 such as JPGs, or prints. Please enclose a stamped, self-addressed envelope if you would like your prints Paid advertising is available in this Journal. Details returned. If possible set your digital camera to take from the Editor. high resolution photos. If photos cannot be emailed, Society website: http://nativeplants-canberra.asn.au make a CD and send it by post. If you have any Printed by Elect Printing, Fyshwick, ACT queries please contact the editor http://www.electprinting.com.au/ Original text may be reprinted, unless otherwise indicated, provided an acknowledgement for the source is given. -

Variation of Physical Seed Dormancy and Its Ecological Role in Fire-Prone Ecosystems

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016 University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2016 Variation of physical seed dormancy and its ecological role in fire-prone ecosystems Ganesha Sanjeewani Liyanage Borala Liyanage University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Borala Liyanage, Ganesha Sanjeewani Liyanage, Variation of physical seed dormancy and its ecological role in fire-prone ecosystems, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Biological Sciences, University of Wollongong, 2016. -

Comparative Floral Presentation and Bee-Pollination in Two Sprengelia Species (Ericaceae)

Comparative floral presentation and bee-pollination in two Sprengelia species (Ericaceae) Karen A. Johnson* and Peter B. McQuillan School of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Tasmania, Private Bag 78, Hobart, Tasmania 7001, Australia. *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Pollination by sonication is unusual in the Styphelioideae, family Ericaceae. Sprengelia incarnata and Sprengelia propinqua have floral characteristics that suggested they might be adapted to buzz pollination.Both species have florally similar nectarless flowers except that the stamens ofSprengelia propinqua spread widely after the flower opens, while those of Sprengelia incarnata cohere in the centre of the flower. To test whether sonication occurs, we observed bee behaviour at the flowers of both plant species, documented potential pollinators, and examined their floral and pollen attributes. We found that Sprengelia incarnata had smaller and drier pollen than Sprengelia propinqua. We found that Sprengelia incarnata was sonicated by native bees in the families Apidae (Exoneura), Halictidae (Lasioglossum) and Colletidae (Leioproctus, Euryglossa). Sprengelia propinqua was also visited by bees from the Apidae (Exoneura) and Halictidae (Lasioglossum), but pollen was collected by scraping. The introduced Apis mellifera (Apidae) foraged at Sprengelia propinqua but ignored Sprengelia incarnata. The two Sprengelia species shared some genera of potential pollinators, but appeared to have diverged enough in their floral and pollen characters to elicit different behaviours from the native and introduced bees. Cunninghamia (2011) 12 (1): 45–51 Introduction species, some Leucopogon species, Richea milliganii (Hook.f.) F.Muell., and Sprengelia incarnata Sm. (Houston The interactions between plants and pollinators are thought & Ladd, 2002; Ladd, 2006). -

Jervis Bay Territory Page 1 of 50 21-Jan-11 Species List for NRM Region (Blank), Jervis Bay Territory

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

Pollination Ecology and Evolution of Epacrids

Pollination Ecology and Evolution of Epacrids by Karen A. Johnson BSc (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania February 2012 ii Declaration of originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. Karen A. Johnson Statement of authority of access This thesis may be made available for copying. Copying of any part of this thesis is prohibited for two years from the date this statement was signed; after that time limited copying is permitted in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Karen A. Johnson iii iv Abstract Relationships between plants and their pollinators are thought to have played a major role in the morphological diversification of angiosperms. The epacrids (subfamily Styphelioideae) comprise more than 550 species of woody plants ranging from small prostrate shrubs to temperate rainforest emergents. Their range extends from SE Asia through Oceania to Tierra del Fuego with their highest diversity in Australia. The overall aim of the thesis is to determine the relationships between epacrid floral features and potential pollinators, and assess the evolutionary status of any pollination syndromes. The main hypotheses were that flower characteristics relate to pollinators in predictable ways; and that there is convergent evolution in the development of pollination syndromes. -

Introduction Methods Results

Papers and Proceedings Royal Society ofTasmania, Volume 1999 103 THE CHARACTERISTICS AND MANAGEMENT PROBLEMS OF THE VEGETATION AND FLORA OF THE HUNTINGFIELD AREA, SOUTHERN TASMANIA by J.B. Kirkpatrick (with two tables, four text-figures and one appendix) KIRKPATRICK, J.B., 1999 (31:x): The characteristics and management problems of the vegetation and flora of the Huntingfield area, southern Tasmania. Pap. Proc. R. Soc. Tasm. 133(1): 103-113. ISSN 0080-4703. School of Geography and Environmental Studies, University ofTasmania, GPO Box 252-78, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia 7001. The Huntingfield area has a varied vegetation, including substantial areas ofEucalyptus amygdalina heathy woodland, heath, buttongrass moorland and E. amygdalina shrubbyforest, with smaller areas ofwetland, grassland and E. ovata shrubbyforest. Six floristic communities are described for the area. Two hundred and one native vascular plant taxa, 26 moss species and ten liverworts are known from the area, which is particularly rich in orchids, two ofwhich are rare in Tasmania. Four other plant species are known to be rare and/or unreserved inTasmania. Sixty-four exotic plantspecies have been observed in the area, most ofwhich do not threaten the native biodiversity. However, a group offire-adapted shrubs are potentially serious invaders. Management problems in the area include the maintenance ofopen areas, weed invasion, pathogen invasion, introduced animals, fire, mechanised recreation, drainage from houses and roads, rubbish dumping and the gathering offirewood, sand and plants. Key Words: flora, forest, heath, Huntingfield, management, Tasmania, vegetation, wetland, woodland. INTRODUCTION species with the most cover in the shrub stratum (dominant species) was noted. If another species had more than half The Huntingfield Estate, approximately 400 ha of forest, the cover ofthe dominant one it was noted as a codominant. -

Table of Contents Below) with Family Name Provided

1 Australian Plants Society Plant Table Profiles – Sutherland Group (updated August 2021) Below is a progressive list of all cultivated plants from members’ gardens and Joseph Banks Native Plants Reserve that have made an appearance on the Plant Table at Sutherland Group meetings. Links to websites are provided for the plants so that further research can be done. Plants are grouped in the categories of: Trees and large shrubs (woody plants generally taller than 4 m) Medium to small shrubs (woody plants from 0.1 to 4 m) Ground covers or ground-dwelling (Grasses, orchids, herbaceous and soft-wooded plants, ferns etc), as well as epiphytes (eg: Platycerium) Vines and scramblers Plants are in alphabetical order by botanic names within plants categories (see table of contents below) with family name provided. Common names are included where there is a known common name for the plant: Table of Contents Trees and Large shrubs........................................................................................................................... 2 Medium to small shrubs ...................................................................................................................... 23 Groundcovers and other ground‐dwelling plants as well as epiphytes. ............................................ 64 Vines and Scramblers ........................................................................................................................... 86 Sutherland Group http://sutherland.austplants.com.au 2 Trees and Large shrubs Acacia decurrens -

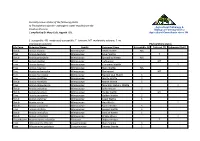

Phytophthora Resistance and Susceptibility Stock List

Currently known status of the following plants to Phytophthora species - pathogenic water moulds from the Agricultural Pathology & Kingdom Protista. Biological Farming Service C ompiled by Dr Mary Cole, Agpath P/L. Agricultural Consultants since 1980 S=susceptible; MS=moderately susceptible; T= tolerant; MT=moderately tolerant; ?=no information available. Phytophthora status Life Form Botanical Name Family Common Name Susceptible (S) Tolerant (T) Unknown (UnK) Shrub Acacia brownii Mimosaceae Heath Wattle MS Tree Acacia dealbata Mimosaceae Silver Wattle T Shrub Acacia genistifolia Mimosaceae Spreading Wattle MS Tree Acacia implexa Mimosaceae Lightwood MT Tree Acacia leprosa Mimosaceae Cinnamon Wattle ? Tree Acacia mearnsii Mimosaceae Black Wattle MS Tree Acacia melanoxylon Mimosaceae Blackwood MT Tree Acacia mucronata Mimosaceae Narrow Leaf Wattle S Tree Acacia myrtifolia Mimosaceae Myrtle Wattle S Shrub Acacia myrtifolia Mimosaceae Myrtle Wattle S Tree Acacia obliquinervia Mimosaceae Mountain Hickory Wattle ? Shrub Acacia oxycedrus Mimosaceae Spike Wattle S Shrub Acacia paradoxa Mimosaceae Hedge Wattle MT Tree Acacia pycnantha Mimosaceae Golden Wattle S Shrub Acacia sophorae Mimosaceae Coast Wattle S Shrub Acacia stricta Mimosaceae Hop Wattle ? Shrubs Acacia suaveolens Mimosaceae Sweet Wattle S Tree Acacia ulicifolia Mimosaceae Juniper Wattle S Shrub Acacia verniciflua Mimosaceae Varnish wattle S Shrub Acacia verticillata Mimosaceae Prickly Moses ? Groundcover Acaena novae-zelandiae Rosaceae Bidgee-Widgee T Tree Allocasuarina littoralis Casuarinaceae Black Sheoke S Tree Allocasuarina paludosa Casuarinaceae Swamp Sheoke S Tree Allocasuarina verticillata Casuarinaceae Drooping Sheoak S Sedge Amperea xipchoclada Euphorbaceae Broom Spurge S Grass Amphibromus neesii Poaceae Swamp Wallaby Grass ? Shrub Aotus ericoides Papillionaceae Common Aotus S Groundcover Apium prostratum Apiaceae Sea Celery MS Herb Arthropodium milleflorum Asparagaceae Pale Vanilla Lily S? Herb Arthropodium strictum Asparagaceae Chocolate Lily S? Shrub Atriplex paludosa ssp. -

Southern Gulf, Queensland

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

Vegetation and Flora of Booti Booti National Park and Yahoo Nature Reserve, Lower North Coast of New South Wales

645 Vegetation and flora of Booti Booti National Park and Yahoo Nature Reserve, lower North Coast of New South Wales. S.J. Griffith, R. Wilson and K. Maryott-Brown Griffith, S.J.1, Wilson, R.2 and Maryott-Brown, K.3 (1Division of Botany, School of Rural Science and Natural Resources, University of New England, Armidale NSW 2351; 216 Bourne Gardens, Bourne Street, Cook ACT 2614; 3Paynes Lane, Upper Lansdowne NSW 2430) 2000. Vegetation and flora of Booti Booti National Park and Yahoo Nature Reserve, lower North Coast of New South Wales. Cunninghamia 6(3): 645–715. The vegetation of Booti Booti National Park and Yahoo Nature Reserve on the lower North Coast of New South Wales has been classified and mapped from aerial photography at a scale of 1: 25 000. The plant communities so identified are described in terms of their composition and distribution within Booti Booti NP and Yahoo NR. The plant communities are also discussed in terms of their distribution elsewhere in south-eastern Australia, with particular emphasis given to the NSW North Coast where compatible vegetation mapping has been undertaken in many additional areas. Floristic relationships are also examined by numerical analysis of full-floristics and foliage cover data for 48 sites. A comprehensive list of vascular plant taxa is presented, and significant taxa are discussed. Management issues relating to the vegetation of the reserves are outlined. Introduction The study area Booti Booti National Park (1586 ha) and Yahoo Nature Reserve (48 ha) are situated on the lower North Coast of New South Wales (32°15'S 152°32'E), immediately south of Forster in the Great Lakes local government area (Fig. -

Post-Fire Recovery of Woody Plants in the New England Tableland Bioregion

Post-fire recovery of woody plants in the New England Tableland Bioregion Peter J. ClarkeA, Kirsten J. E. Knox, Monica L. Campbell and Lachlan M. Copeland Botany, School of Environmental and Rural Sciences, University of New England, Armidale, NSW 2351, AUSTRALIA. ACorresponding author; email: [email protected] Abstract: The resprouting response of plant species to fire is a key life history trait that has profound effects on post-fire population dynamics and community composition. This study documents the post-fire response (resprouting and maturation times) of woody species in six contrasting formations in the New England Tableland Bioregion of eastern Australia. Rainforest had the highest proportion of resprouting woody taxa and rocky outcrops had the lowest. Surprisingly, no significant difference in the median maturation length was found among habitats, but the communities varied in the range of maturation times. Within these communities, seedlings of species killed by fire, mature faster than seedlings of species that resprout. The slowest maturing species were those that have canopy held seed banks and were killed by fire, and these were used as indicator species to examine fire immaturity risk. Finally, we examine whether current fire management immaturity thresholds appear to be appropriate for these communities and find they need to be amended. Cunninghamia (2009) 11(2): 221–239 Introduction Maturation times of new recruits for those plants killed by fire is also a critical biological variable in the context of fire Fire is a pervasive ecological factor that influences the regimes because this time sets the lower limit for fire intervals evolution, distribution and abundance of woody plants that can cause local population decline or extirpation (Keith (Whelan 1995; Bond & van Wilgen 1996; Bradstock et al.