Initial Response Ofsmall Ground-Dwelling Mammals to Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Environmental Assessment Report

2 Greenwood and Kealy Woods Park Urban Forest Environmental Assessment Report July 20, 2020 Submitted to: City of North Vancouver 141 West 14th Street North Vancouver V7M 1H9 Greenwood and Kealy Woods Park Environmental Assessment Report Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................4 2.0 EXISTING CONDITIONS ............................................................................................................5 2.1 Topography .................................................................................................................................................. 5 2.2 Biogeoclimatic Classification ........................................................................................................................ 7 2.3 Forest Stands ................................................................................................................................................ 8 2.4 Understory Vegetation ............................................................................................................................... 12 2.5 Invasive plant species ................................................................................................................................. 13 2.6 Watercourses ............................................................................................................................................. 15 2.7 Wildlife ...................................................................................................................................................... -

British Columbia Listed Mammal Species

British Columbia Listed Mammal Species Mammals English Name Scientific Name BC List COSEWIC List SARA List BC Species Code Caribou dawsoni subspecies Rangifer tarandus dawsoni Extinct Extinct M-RATA-DA American Badger Taxidea taxus Red Endangered Endangered M-TATA Blue Whale Balaenoptera musculus Red Endangered Endangered M-BAMU North Pacific Right Whale Eubalaena japonica Red Endangered Endangered M-EUJA Sei Whale Balaenoptera borealis Red Endangered Endangered M-BABO Killer Whale (southern resident population) Orcinus orca pop. 5 Red Endangered Endangered M-OROR-05 Vancouver Island Marmot Marmota vancouverensis Red Endangered Endangered M-MAVA Townsend's Mole Scapanus townsendii Red Endangered Endangered M-SCTO Pacific Water Shrew Sorex bendirii Red Endangered Endangered M-SOBE Plains Bison Bos bison bison Red Threatened M-BOBI-BI Wood Bison Bos bison athabascae Red Threatened Threatened M-BOBI-AT Caribou (southern mountain population) Rangifer tarandus pop. 1 Red Threatened Threatened M-RATA-01 Caribou (boreal population) Rangifer tarandus pop. 14 Red Threatened Threatened M-RATA-14 Ermine, haidarum subspecies Mustela erminea haidarum Red Threatened Threatened M-MUER-HA Northern Fur Seal Callorhinus ursinus Red Threatened M-CAUR Fin Whale Balaenoptera physalus Red Threatened Threatened M-BAPH Killer Whale (offshore population) Orcinus orca pop. 2 Red Threatened Threatened M-OROR-02 Killer Whale (transient population) Orcinus orca pop. 3 Red Threatened Threatened M-OROR-03 Killer Whale (northern resident population) Orcinus orca pop. -

List of 28 Orders, 129 Families, 598 Genera and 1121 Species in Mammal Images Library 31 December 2013

What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library LIST OF 28 ORDERS, 129 FAMILIES, 598 GENERA AND 1121 SPECIES IN MAMMAL IMAGES LIBRARY 31 DECEMBER 2013 AFROSORICIDA (5 genera, 5 species) – golden moles and tenrecs CHRYSOCHLORIDAE - golden moles Chrysospalax villosus - Rough-haired Golden Mole TENRECIDAE - tenrecs 1. Echinops telfairi - Lesser Hedgehog Tenrec 2. Hemicentetes semispinosus – Lowland Streaked Tenrec 3. Microgale dobsoni - Dobson’s Shrew Tenrec 4. Tenrec ecaudatus – Tailless Tenrec ARTIODACTYLA (83 genera, 142 species) – paraxonic (mostly even-toed) ungulates ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BOVIDAE (46 genera) - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Addax nasomaculatus - Addax 2. Aepyceros melampus - Impala 3. Alcelaphus buselaphus - Hartebeest 4. Alcelaphus caama – Red Hartebeest 5. Ammotragus lervia - Barbary Sheep 6. Antidorcas marsupialis - Springbok 7. Antilope cervicapra – Blackbuck 8. Beatragus hunter – Hunter’s Hartebeest 9. Bison bison - American Bison 10. Bison bonasus - European Bison 11. Bos frontalis - Gaur 12. Bos javanicus - Banteng 13. Bos taurus -Auroch 14. Boselaphus tragocamelus - Nilgai 15. Bubalus bubalis - Water Buffalo 16. Bubalus depressicornis - Anoa 17. Bubalus quarlesi - Mountain Anoa 18. Budorcas taxicolor - Takin 19. Capra caucasica - Tur 20. Capra falconeri - Markhor 21. Capra hircus - Goat 22. Capra nubiana – Nubian Ibex 23. Capra pyrenaica – Spanish Ibex 24. Capricornis crispus – Japanese Serow 25. Cephalophus jentinki - Jentink's Duiker 26. Cephalophus natalensis – Red Duiker 1 What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library 27. Cephalophus niger – Black Duiker 28. Cephalophus rufilatus – Red-flanked Duiker 29. Cephalophus silvicultor - Yellow-backed Duiker 30. Cephalophus zebra - Zebra Duiker 31. Connochaetes gnou - Black Wildebeest 32. Connochaetes taurinus - Blue Wildebeest 33. Damaliscus korrigum – Topi 34. -

Ef-Funa Mammal Checklist 2014 Version

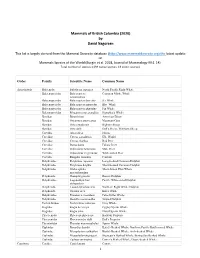

Mammals of British Columbia (2020) by David Nagorsen This list is largely derived from the Mammal Diversity database (http://www.mammaldiversity.org) the latest update on Mammals Species of the World (Burgin et al. 2018, Journal of Mammalogy 99:1-14) . Total number of species: (139 native species; 13 exotic species). Order Family Scientific Name Common Name Artiodactyla Balaenidae Eubalaena japonica North Pacific Right Whale Balaenopteridae Balaenoptera Common Minke Whale acutorostrata Balaenopteridae Balaenoptera borealis Sei Whale Balaenopteridae Balaenoptera musculus Blue Whale Balaenopteridae Balaenoptera physalus Fin Whale Balaenopteridae Megaptera novaeangliae Humpback Whale Bovidae Bison bison American Bison Bovidae Oreamnos americanus Mountain Goat Bovidae Ovis canadensis Bighorn Sheep Bovidae Ovis dalli Dall's Sheep, Thinhorn Sheep Cervidae Alces alces Moose Cervidae Cervus canadensis Elk, Wapiti Cervidae Cervus elaphus Red Deer Cervidae Dama dama Fallow Deer Cervidae Odocoileus hemionus Mule Deer Cervidae Odocoileus virginianus White‐tailed Deer Cervidae Rangifer tarandus Caribou Delphinidae Delphinus capensis Long‐beaked Common Dolphin Delphinidae Delphinus delphis Short‐beaked Common Dolphin Delphinidae Globicephala Short‐finned Pilot Whale macrorhynchus Delphinidae Grampus griseus Risso's Dolphin Delphinidae Lagenorhynchus Pacific White‐sided Dolphin obliquidens Delphinidae Lissodelphis borealis Northern Right Whale Dolphin Delphinidae Orcinus orca Killer Whale Delphinidae Pseudorca crassidens False Killer Whale Delphinidae -

List of Taxa for Which MIL Has Images

LIST OF 27 ORDERS, 163 FAMILIES, 887 GENERA, AND 2064 SPECIES IN MAMMAL IMAGES LIBRARY 31 JULY 2021 AFROSORICIDA (9 genera, 12 species) CHRYSOCHLORIDAE - golden moles 1. Amblysomus hottentotus - Hottentot Golden Mole 2. Chrysospalax villosus - Rough-haired Golden Mole 3. Eremitalpa granti - Grant’s Golden Mole TENRECIDAE - tenrecs 1. Echinops telfairi - Lesser Hedgehog Tenrec 2. Hemicentetes semispinosus - Lowland Streaked Tenrec 3. Microgale cf. longicaudata - Lesser Long-tailed Shrew Tenrec 4. Microgale cowani - Cowan’s Shrew Tenrec 5. Microgale mergulus - Web-footed Tenrec 6. Nesogale cf. talazaci - Talazac’s Shrew Tenrec 7. Nesogale dobsoni - Dobson’s Shrew Tenrec 8. Setifer setosus - Greater Hedgehog Tenrec 9. Tenrec ecaudatus - Tailless Tenrec ARTIODACTYLA (127 genera, 308 species) ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BALAENIDAE - bowheads and right whales 1. Balaena mysticetus – Bowhead Whale 2. Eubalaena australis - Southern Right Whale 3. Eubalaena glacialis – North Atlantic Right Whale 4. Eubalaena japonica - North Pacific Right Whale BALAENOPTERIDAE -rorqual whales 1. Balaenoptera acutorostrata – Common Minke Whale 2. Balaenoptera borealis - Sei Whale 3. Balaenoptera brydei – Bryde’s Whale 4. Balaenoptera musculus - Blue Whale 5. Balaenoptera physalus - Fin Whale 6. Balaenoptera ricei - Rice’s Whale 7. Eschrichtius robustus - Gray Whale 8. Megaptera novaeangliae - Humpback Whale BOVIDAE (54 genera) - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Addax nasomaculatus - Addax 2. Aepyceros melampus - Common Impala 3. Aepyceros petersi - Black-faced Impala 4. Alcelaphus caama - Red Hartebeest 5. Alcelaphus cokii - Kongoni (Coke’s Hartebeest) 6. Alcelaphus lelwel - Lelwel Hartebeest 7. Alcelaphus swaynei - Swayne’s Hartebeest 8. Ammelaphus australis - Southern Lesser Kudu 9. Ammelaphus imberbis - Northern Lesser Kudu 10. Ammodorcas clarkei - Dibatag 11. Ammotragus lervia - Aoudad (Barbary Sheep) 12. -

Biodiversity Conservation Strategy Part4

Backyard Biodiversity Planning for habitat in the urban matrix should include less maintenance. Ground cover (logs, rock piles, dense features, either natural or artificial, that will support the shrubs) provide important refuge areas for wildlife. three basic needs of wildlife: Artificial habitat such as nesting boxes and bee hives can provide great benefit; however they do require maintenance. • Shelter In developed areas, access to water can be scarce. Provision of a water feature is very important. This can be as simple • Food as a bird bath. Consideration should be given to reducing • Water unwanted conflicts with wildlife. This includes control of pets (cats/dogs), reducing bird-window collisions and man- Indigenous plants should be used where possible. These aging waste to discourage pests and vermin. plants are adapted to local conditions and generally require Spring 2014 • BCS 73 Engineered Habitat Features Other opportunities within the Urban Matrix to support the GIN include implementation Integration of these features should continue to be encouraged when replacing aging in- of constructed features that mimic natural habitat and functions. Examples include frastructure and re-developing streetscapes. Engineered habitat should also be considered bioswales, constructed wetlands, stormwater detention ponds, rain gardens, green at the development permit stage of larger projects. Cumulatively, these features contrib- streets, permeable pavement, green roofs and walls. Many of these features replace ute to support biodiversity in highly urbanized areas where it is not possible to protect conventional grey infrastructure (e.g. pipes, culverts, pavement) and reduce the amount larger areas of natural habitat. of hard surface on a landscape. Surrey’s Integrated Stormwater Management Plan supports the use of many of these strategies, alternatively known as Low Impact Design (LID). -

Mammal Species Native to the USA and Canada for Which the MIL Has No Image (170) 31 July 2021

Mammal species native to the USA and Canada for which the MIL has no image (170) 31 July 2021 ARTIODACTYLA (includes CETACEA) (25) BALAENIDAE - bowheads and right whales 1. Eubalaena japonica - Northern Pacific Right Whale 2. Eubalaena glacialis – North Atlantic Right Whale BALAENOPTERIDAE - rorqual whales Balaenoptera ricei - Rice’s Whale DELPHINIDAE - ocean dolphins 1. Feresa attenuata - Pygmy Killer Whale 2. Globicephala melas - Long-finned Pilot Whale 3. Lagenodelphis hosei - Fraser’s Dolphin 4. Leucopleurus acutus - Atlantic White-sided Dolphin 5. Stenella attenuata - Pantropical Spotted Dolphin 6. Stenella clymene - Clymene Dolphin 7. Stenella longirostris - Spinner Dolphin KOGIIDAE - pygmy sperm whales 1. Kogia breviceps - Pygmy Sperm Whale 2. Kogia sima - Dwarf Sperm Whale ZIPHIIDAE - beaked whales 1. Berardius bairdii - Baird’s Beaked Whale 2. Berardius minimus - Least Beaked Whale 3. Hyperoodon ampullatus - Northen Bottlenose Whale 4. Indopacetus pacificus - Tropical Beaked Whale 5. Mesoplodon bidens - Sowerby’s Beaked Whale 6. Mesoplodon carlhubbsi – Hubbs’s Beaked Whale 7. Mesoplodon densirostris - Blainville’s Beaked Whale 8. Mesoplodon europaeus - Gervais’s Beaked Whale 9. Mesoplodon ginkgodens - Ginkgo-toothed Beaked Whale 10. Mesoplodon mirus - True’s Beaked Whale 11. Mesoplodon perrini - Perrin’s Beaked Whale 12. Mesoplodon stejnegeri - Stejneger’s Beaked Whale 13. Ziphius cavirostris - Cuvier’s Beaked Whale CARNIVORA (8) CANIDAE - dogs Canis lycaon - Eastern Wolf MEPHITIDAE - skunks 1. Conepatus leuconotus - American Hog-nosed Skunk 2. Spilogale gracilis - Western Spotted Skunk MUSTELIDAE - weasels and relatives Martes americana - American Marten OTARIIDAE - eared seals Arctocephalus townsendi - Guadalupe Fur Seal PHOCIDAE - earless seals 1. Cystophora cristata - Hooded Seal 2. Histriophoca fasciata - Ribbon Seal 3. Phoca largha - Spotted Seal CHIROPTERA (20) MOLOSSIDAE - free-tailed bats 1. -

South Lewis County Habitat Analysis Report

Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife South Lewis County Habitat Analysis Report John Carleton, Conservation Planner John Jacobson, Geographic Information Systems Analyst 5/14/2009 South Lewis County Habitat Analysis Report Introduction To inform the South Lewis County Subarea planning process, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) and Washington Department of Ecology (Ecology) were consulted to analyze habitats and ecosystem processes, respectively, across the local area. The purpose of the two agencies’ work is to provide information on natural systems that will allow the planners to accommodate growth while avoiding unintended consequences, such as loss of local biodiversity, or increased flooding. This habitat report is to be incorporated as an appendix to the watershed characterization. South County Subarea The south county subarea, shown on the right, was drawn as a rectangular zone incorporating the cities of Winlock, Toledo, and Vader, plus some of the surrounding unincorporated county. As of 2008, population in the subarea was approximately 10,200. Although the three cities have concentrations of residences and businesses, most of the subarea is rural, with agriculture and residential land uses predominant, and with a significant portion of undeveloped land. Figure 1. South Lewis County Subarea The primary landform feature is a series of relatively flat terraces at increasing elevation, leading away from the Cowlitz River. Forested habitats include conifer and mixed conifer/hardwood; oak woodlands are a minor component. A major portion of the land was historically prairie, now largely converted to agricultural use, although featuring patches of remnant native vegetation. Cowlitz River and several tributaries run across the subarea. -

The Hostassociations of the Lice of Mammals

rhe Host-asociatioii\ of the lice of mainiiials . I35 (i. I! . J<'. HOPKLYS. MA.,O.K.E., F.R.E.S.. late. Senior 13 ntoniologist (Xedic al), Cgaiida Protectors te . [Keceived .liiiic. 7. I04h 1 (With 1 figlire 111 the. tcst.) Cumi*;sw. 1 . IXTIWDGI;T~OS............................................ (I) (4 oneral .......................................... (2) The classificat.ion of the lice of triammals ....... (3) What is a species .................... ....... (4j Thc extent. of our kiiowledye ....................... (3) AMetlliodsof' collecting lice frorn inammills .............. (ti) ,Methods of I)reservut.iw and vsarniria.tiori of liri: ...... (7) Aeknowledgnients ......................... 11. U1OLoc:Y OF L1O.E ......................................... (1) General ......................................... (2) Food ............................................ (:3 j Keaet.ions t.o trmperd lire ......................... (4)Ecologicel niches ................................. ( .7 ) Loiise-pop.ilat. ions of host-individuals ................ (ti) (:omposition of loiist?-~~op~~l~tio~i~..... (7) Effect on the host ................................ (8) Natural enemies ................................ (9) Symbiotic organisms ........................... I 10) Transfer from host to host. .......................... (1 I) Host-specificity ............. (1 2) Straggling and runt.amination ...................... ( 13) Primary and secondary infestittioris ................. (14) Secondary ahwncc .... ( 15) Geographical factors ............................. -

Line 2 Construction, Operations and Emergency Response

REPORT 3 Application Summary: Line 2 Construction, Operations and Emergency Response 3.1 Overview This section describes the Proposed and Alternate Routes that were assessed, and includes a summary of the planning, construction and emergency response processes that Trans Mountain proposes in their application to the NEB (referred to hereafter as the Application). Because of the broad spatial scope of Trans Mountain’s Application, SBRP is rarely mentioned in any of the documents. This section considers the regulatory requirements that Trans Mountain must meet during construction and operations, and indicates how these are likely to guide Trans Mountain’s construction and operations activities in and around SBRP. 3.2 Proposed and Alternate Routes The Proposed Route (orange) and Alternate Routes (Option A- yellow; Option B-pink) are identified in Figure 1-1. Trans Mountain’s Proposed Route enters the southeast portion of the park at the intersection of Trigg Road and 104th Avenue, and extends west adjacent to 104th Avenue to the CN rail tracks. This route would follow the east side of the tracks past Centre Creek for approximately 900 m before crossing beneath the railway tracks and the SFPR. Both Alternate Routes avoid SBRP entirely. The Option A route is located between the CN Rail Corridor and the Golden Ears Connector to the south of the park; it crosses 104th Avenue and follows the corridor between SFPR and the CN tracks. The Option B route extends along the SFPR on the southwest side of the road. 3.3 Pipeline Design and Construction 3.3.1 Guiding Legislation Trans Mountain’s proposed expansion project falls under the regulatory jurisdiction of the NEB under the National Energy Board Act, the regulatory requirements of the NEB Onshore Pipeline Regulations (OPR), and the regulatory requirements of the following: Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency; Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO); Transport Canada; and Affected municipal, provincial, rail and utility authorities. -

Fraser Valley Regional Biodiversity Strategy I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Conserving Biodiversity: Fostering Partnerships & Preserving Life December 2010 PREFACE The Fraser Valley Conservancy (FVC) is a not for profit charitable organization located within the Fraser Valley of British Columbia. It is dedicated to placing lands in trust for our future. As such, the organization believes that the Fraser Valley is a collage of biologically diverse habitats which should be valued and protected. FVC has mandated goals to, i) protect and preserve the land and watercourses that have recognized local and regional ecological value; ii) to promote, facilitate and engage in land stewardship activities; iii) to protect, preserve and enhance habitat for native species including rare and endangered species, and; iv) to protect and preserve land of recognized local and regional historic value. www.fraservalleyconservancy.ca Fraser Valley Regional Biodiversity Strategy I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This document presents a need for a strategy that outlines preservation, conservation and restoration measures to protect biodiversity in the Fraser Valley. This document describes opportunities for various existing conservation efforts to be synchronized and how current gaps in data can be filled. This process was initiated in 2009 and will provide support to current and ongoing stewardship and biodiversity actions. It is a regionally based planning and conservation initiative that will increase partnerships and collaboration between Fraser Valley stewardship groups and all levels of government. The intent is to support the work of Fraser Valley organizations in the conservation and enhancement of biodiversity and will aid in the dissemination of and access to scientific and conservation data. This information will also reveal where there are gaps in data sets that create barriers to effective biodiversity enhancement and protection (FVC 2009). -

Saqartvelos Erovnuli Muzeumis Bibliotekis Inglisurenovani Gamocemebis Koleqcia

ivane menTeSaSvili saqarTvelos erovnuli muzeumis biblioTekis inglisurenovani gamocemebis koleqcia Ivane Menteshashvili THE COLLECTION OF ENGLISH PUBLICATIONS AT THE LIBRARY OF GEORGIAN NATIONAL MUSEUM saqarTvelos erovnuli muzeumi Georgian National Museum Tbilisi 2011 Tbilisi redaqtori: daviT lorTqifaniZe gamocemaze muSaobdnen: nino andriaSvili, magda cocxalaSvili, irakli xuciSvili ISBN 978-9941-9105-7-9 © saqarTvelos erovnuli muzeumi, 2011 wi na sity va o ba sa qar Tve los erov nu li mu ze u mis s. ja na Sias sa xe lo bis sa qar Tve los mu ze u mi qveynis uZ ve le si kultu rul -sa gan ma naT leblo da sa mec nie ro ke ra a. mu ze um Si da cul mra val ricx o van nivTTan er Tad, rom le bic ma te- ri a lu ri da su li e ri kul tu ris um niSvne lo va nes Zeglebs war mo ad ge nen uda vod aR sa niS na via wig ne bis unika lu ri ko leq ci a. dRe i saT vis mu ze u- mis bib li o Te kis ka ta log Si re gistri re bu lia 248 931 wig ni, aqe dan 124 054 ucxo ena ze. ucxo ena ze ar se bul wignebs So ris yu radR e bas uda vod im sa xu rebs ingli su re no va ni li te ra tu ra, rom lis da sa xe le ba Ta ra o- de no ba 4 517 ud ris. am ko leq ci a Si da cu lia wig ne bi, rom le bic mTel in- glisu re no van sam ya ros mo i cavs.