Military Space Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L AUNCH SYSTEMS Databk7 Collected.Book Page 18 Monday, September 14, 2009 2:53 PM Databk7 Collected.Book Page 19 Monday, September 14, 2009 2:53 PM

databk7_collected.book Page 17 Monday, September 14, 2009 2:53 PM CHAPTER TWO L AUNCH SYSTEMS databk7_collected.book Page 18 Monday, September 14, 2009 2:53 PM databk7_collected.book Page 19 Monday, September 14, 2009 2:53 PM CHAPTER TWO L AUNCH SYSTEMS Introduction Launch systems provide access to space, necessary for the majority of NASA’s activities. During the decade from 1989–1998, NASA used two types of launch systems, one consisting of several families of expendable launch vehicles (ELV) and the second consisting of the world’s only partially reusable launch system—the Space Shuttle. A significant challenge NASA faced during the decade was the development of technologies needed to design and implement a new reusable launch system that would prove less expensive than the Shuttle. Although some attempts seemed promising, none succeeded. This chapter addresses most subjects relating to access to space and space transportation. It discusses and describes ELVs, the Space Shuttle in its launch vehicle function, and NASA’s attempts to develop new launch systems. Tables relating to each launch vehicle’s characteristics are included. The other functions of the Space Shuttle—as a scientific laboratory, staging area for repair missions, and a prime element of the Space Station program—are discussed in the next chapter, Human Spaceflight. This chapter also provides a brief review of launch systems in the past decade, an overview of policy relating to launch systems, a summary of the management of NASA’s launch systems programs, and tables of funding data. The Last Decade Reviewed (1979–1988) From 1979 through 1988, NASA used families of ELVs that had seen service during the previous decade. -

Gallery of USAF Weapons Note: Inventory Numbers Are Total Active Inventory figures As of Sept

Gallery of USAF Weapons Note: Inventory numbers are total active inventory figures as of Sept. 30, 2014. By Aaron M. U. Church, Associate Editor I 2015 USAF Almanac BOMBER AIRCRAFT flight controls actuate trailing edge surfaces that combine aileron, elevator, and rudder functions. New EHF satcom and high-speed computer upgrade B-1 Lancer recently entered full production. Both are part of the Defensive Management Brief: A long-range bomber capable of penetrating enemy defenses and System-Modernization (DMS-M). Efforts are underway to develop a new VLF delivering the largest weapon load of any aircraft in the inventory. receiver for alternative comms. Weapons integration includes the improved COMMENTARY GBU-57 Massive Ordnance Penetrator and JASSM-ER and future weapons The B-1A was initially proposed as replacement for the B-52, and four pro- such as GBU-53 SDB II, GBU-56 Laser JDAM, JDAM-5000, and LRSO. Flex- totypes were developed and tested in 1970s before program cancellation in ible Strike Package mods will feed GPS data to the weapons bays to allow 1977. The program was revived in 1981 as B-1B. The vastly upgraded aircraft weapons to be guided before release, to thwart jamming. It also will move added 74,000 lb of usable payload, improved radar, and reduced radar cross stores management to a new integrated processor. Phase 2 will allow nuclear section, but cut maximum speed to Mach 1.2. The B-1B first saw combat in and conventional weapons to be carried simultaneously to increase flexibility. Iraq during Desert Fox in December 1998. -

Beyond the Paths of Heaven the Emergence of Space Power Thought

Beyond the Paths of Heaven The Emergence of Space Power Thought A Comprehensive Anthology of Space-Related Master’s Research Produced by the School of Advanced Airpower Studies Edited by Bruce M. DeBlois, Colonel, USAF Professor of Air and Space Technology Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama September 1999 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Beyond the paths of heaven : the emergence of space power thought : a comprehensive anthology of space-related master’s research / edited by Bruce M. DeBlois. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Astronautics, Military. 2. Astronautics, Military—United States. 3. Space Warfare. 4. Air University (U.S.). Air Command and Staff College. School of Advanced Airpower Studies- -Dissertations. I. Deblois, Bruce M., 1957- UG1520.B48 1999 99-35729 358’ .8—dc21 CIP ISBN 1-58566-067-1 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. ii Contents Chapter Page DISCLAIMER . ii OVERVIEW . ix PART I Space Organization, Doctrine, and Architecture 1 An Aerospace Strategy for an Aerospace Nation . 3 Stephen E. Wright 2 After the Gulf War: Balancing Space Power’s Development . 63 Frank Gallegos 3 Blueprints for the Future: Comparing National Security Space Architectures . 103 Christian C. Daehnick PART II Sanctuary/Survivability Perspectives 4 Safe Heavens: Military Strategy and Space Sanctuary . 185 David W. Ziegler PART III Space Control Perspectives 5 Counterspace Operations for Information Dominance . -

Program Acquisition Cost by Weapon System Major Weapon Systems OVERVIEW

The estimated cost of this report or study for the Department of Defense is approximately $32,000 for the 2017 Fiscal Year. This includes $13,000 in expenses and $19,000 in DoD labor. Generated on 2017May03 RefID: E-7DE12B0 FY 2018 Program Acquisition Cost by Weapon System Major Weapon Systems OVERVIEW The combined capabilities and performance of United States (U.S.) weapon systems are unmatched throughout the world, ensuring that U.S. military forces have the advantage over any adversary. The Fiscal Year (FY) 2018 acquisition funding request for the Department of Defense (DoD) budget totals $208.6 billion, which includes base funding and Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) funding; $125.2 billion for Procurement funded programs and $83.3 billion for Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation (RDT&E) funded programs. Of the $208.6 billion, $94.9 billion is for programs that have been designated as Major Defense Acquisition Programs (MDAPs). This book focuses on all funding for the key MDAP programs. To simplify the display of the various weapon systems, this book is organized by the following mission area categories: Mission Area Categories • Aircraft & Related Systems • Missiles and Munitions • Command, Control, Communications, • Mission Support Activities Computers, and Intelligence (C4I) Systems • RDT&E Science & Technology • Ground Systems • Shipbuilding and Maritime Systems • Missile Defense Programs • Space Based Systems FY 2018 Modernization – Total: $208.6 Billion ($ in Billions) Space Based Aircraft & Systems Related $9.8 -

IMTEC-89-53 Military Space Operations: Use of Mobile Ground

. -. ,(. ,. .“” ,Y .,, . -- II, ./, .I i /, . % . ,L. United States Gdneral Accounting Off& Report to the Honorable &.A0 John P. Murtha, Chairman, Subcommittee on Defense, Committee on Appropriations, House of Representatives July 1989 MILITARY SPACE ’ OPERATIONS Use of Mobile Ground Stations in Satellite Control GAO/IMTEC439-63 United States General Accounting Office GAO Washington, D.C. 20548 Information Management and Technology Division B-224148 July 3, 1989 The Honorable John P. Murtha Chairman, Subcommittee on Defense Committee on Appropriations House of Representatives Dear Mr. Chairman: In your January 9, 1989, letter and in subsequent discussions with your office, you asked us to determine (1) how mobile ground stations fit into the Air Force’s overall satellite control architecture, (2) how many sta- tions exist and are planned, (3) what they cost by program element and appropriation account, and (4) how much the Department of Defense budgeted in fiscal year 1990 for mobile ground stations. As agreed with your office, our review focused primarily on mobile ground stations used by the Air Force’s satellite programs and included mobile ground stations used for one Defense Communications Agency satellite program. The Air Force’s satellite control architecture establishes a requirement for mobile ground stations to provide command and control instructions to maintain the position of a satellite in orbit as well as to provide the capability to process information coming from satellites. This network of stations, when completed, is planned to supplement fixed stations and/or to totally command and control a satellite’s position in orbit or process information. As of May 1989, there were 39 existing mobile ground stations. -

National Reconnaissance Office Review and Redaction Guide

NRO Approved for Release 16 Dec 2010 —Tep-nm.T7ymqtmthitmemf- (u) National Reconnaissance Office Review and Redaction Guide For Automatic Declassification Of 25-Year-Old Information Version 1.0 2008 Edition Approved: Scott F. Large Director DECL ON: 25x1, 20590201 DRV FROM: NRO Classification Guide 6.0, 20 May 2005 NRO Approved for Release 16 Dec 2010 (U) Table of Contents (U) Preface (U) Background 1 (U) General Methodology 2 (U) File Series Exemptions 4 (U) Continued Exemption from Declassification 4 1. (U) Reveal Information that Involves the Application of Intelligence Sources and Methods (25X1) 6 1.1 (U) Document Administration 7 1.2 (U) About the National Reconnaissance Program (NRP) 10 1.2.1 (U) Fact of Satellite Reconnaissance 10 1.2.2 (U) National Reconnaissance Program Information 12 1.2.3 (U) Organizational Relationships 16 1.2.3.1. (U) SAF/SS 16 1.2.3.2. (U) SAF/SP (Program A) 18 1.2.3.3. (U) CIA (Program B) 18 1.2.3.4. (U) Navy (Program C) 19 1.2.3.5. (U) CIA/Air Force (Program D) 19 1.2.3.6. (U) Defense Recon Support Program (DRSP/DSRP) 19 1.3 (U) Satellite Imagery (IMINT) Systems 21 1.3.1 (U) Imagery System Information 21 1.3.2 (U) Non-Operational IMINT Systems 25 1.3.3 (U) Current and Future IMINT Operational Systems 32 1.3.4 (U) Meteorological Forecasting 33 1.3.5 (U) IMINT System Ground Operations 34 1.4 (U) Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) Systems 36 1.4.1 (U) Signals Intelligence System Information 36 1.4.2 (U) Non-Operational SIGINT Systems 38 1.4.3 (U) Current and Future SIGINT Operational Systems 40 1.4.4 (U) SIGINT -

Usafalmanac ■ Gallery of USAF Weapons

USAFAlmanac ■ Gallery of USAF Weapons By Susan H.H. Young The B-1B’s conventional capability is being significantly enhanced by the ongoing Conventional Mission Upgrade Program (CMUP). This gives the B-1B greater lethality and survivability through the integration of precision and standoff weapons and a robust ECM suite. CMUP will include GPS receivers, a MIL-STD-1760 weapon interface, secure radios, and improved computers to support precision weapons, initially the JDAM, followed by the Joint Standoff Weapon (JSOW) and the Joint Air to Surface Standoff Missile (JASSM). The Defensive System Upgrade Program will improve aircrew situational awareness and jamming capability. B-2 Spirit Brief: Stealthy, long-range, multirole bomber that can deliver conventional and nuclear munitions anywhere on the globe by flying through previously impenetrable defenses. Function: Long-range heavy bomber. Operator: ACC. First Flight: July 17, 1989. Delivered: Dec. 17, 1993–present. B-1B Lancer (Ted Carlson) IOC: April 1997, Whiteman AFB, Mo. Production: 21 planned. Inventory: 21. Unit Location: Whiteman AFB, Mo. Contractor: Northrop Grumman, with Boeing, LTV, and General Electric as principal subcontractors. Bombers Power Plant: four General Electric F118-GE-100 turbo fans, each 17,300 lb thrust. B-1 Lancer Accommodation: two, mission commander and pilot, Brief: A long-range multirole bomber capable of flying on zero/zero ejection seats. missions over intercontinental range without refueling, Dimensions: span 172 ft, length 69 ft, height 17 ft. then penetrating enemy defenses with a heavy load Weight: empty 150,000–160,000 lb, gross 350,000 lb. of ordnance. Ceiling: 50,000 ft. Function: Long-range conventional bomber. -

GAO-15-366, SPACE ACQUISITIONS: Space Based

United States Government Accountability Office Report to the Committee on Armed Services, U.S. Senate April 2015 SPACE ACQUISITIONS Space Based Infrared System Could Benefit from Technology Insertion Planning GAO-15-366 April 2015 SPACE ACQUISITIONS Space Based Infrared System Could Benefit from Technology Insertion Planning Highlights of GAO-15-366, a report to the Committee on Armed Services, U.S. Senate Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found SBIRS is a key part of DOD’s missile The Air Force assessed options for replacing older technologies with newer warning and defense systems. To ones—called technology insertion—in the Space Based Infrared System (SBIRS) replace the first two satellites currently geosynchronous earth orbit (GEO) satellites 5 and 6. However, the assessment on orbit, the Air Force plans to build was limited in the number of options it could practically consider because of two more with the same design as timing and minimal early investment in technology planning. The Air Force previous satellites. The basic SBIRS assessed the feasibility and cost of inserting new digital infrared focal plane design is years old and some of its technology—used to provide surveillance, tracking, and targeting information for technology has become obsolete. To national missile defense and other missions—in place of the current analog focal address obsolescence issues in the plane, either with or without changing the related electronics. While technically next satellites, the program must feasible, neither option was deemed affordable or deliverable when needed. The replace old technologies with new ones, a process that may be referred Air Force estimated that inserting new focal plane technology would result in cost to as technology insertion or refresh. -

NSIAD-86-45S-15 DOD Acquisition: Case Study of the MILSTAR

United States General Accounting Office 1305sq GAO Report to Congressional Requesters July 31,1986 DOD ACQUISITION Case Study of the MILSTAR Satellite Communications System IIllIlllIillll IIIII 130589 GAOl/MAD-f3S-4SS-l6 036aa3 /3Os8P I / Preface The Chairmen of the Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs and its Subcommittee on Oversight of Government Management asked GAO to examine the capabilities of the program manager and contracting officer in weapon systems acquisition. As part of this study, GAO examined 17 new major weapon system programs in their initial stages of develop ment. These casestudies document the history of the programs and are being made available for informational purposes. This study of the Military Strategic and Tactical Relay (MUTAR) pro- gram focuses on the role of the program manager and contracting officer in developing the acquisition strategy. Conclusions and recommenda- tions can be found in our overall report, DOD Acquisition: Strengthening Capabilities of Key Personnel in Systems Acauisition (GAO/NSL4D-86-46, May 12,1986). Frank C. Conahan, Director . National Security and International Affairs Division Page 1 GAO/NSIADM4S-15 Defense Acquisition Work Force The MILSTm Program The Military Strategic and Tactical Relay (MUTAR) Satellite Communica- Origin of the Program tions System is being developedjointly by the Air Force, Navy, and Army. The system is designedto meet the minimum essential wartime communication needsof the President and Commanders-in-Chief to com- mand and control our strategic and tactical forces through all levels of conflict. MIISTAR will be composedof satellites in geostationary orbit (about 22,894 nautical miles above the center of the earth) and other comple- mentary orbits that will be crosslinked for worldwide coverage.The system will use the extremely high frequency band to prevent jamming. -

Concerns with Milstar's Support to Strategic and Tactical Forces

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Chairman, Subcommittee GAO on National Security, Committee on Appropriations, House of Representatives November 1998 MILITARY SATELLITE COMMUNICATIONS Concerns With Milstar’s Support to Strategic and Tactical Forces GAO/NSIAD-99-2 United States General Accounting Office GAO Washington, D.C. 20548 National Security and International Affairs Division B-278426 November 10, 1998 The Honorable C. W. Bill Young Chairman, Subcommittee on National Security Committee on Appropriations House of Representatives Dear Mr. Chairman: The Department of Defense’s (DOD) multiservice Milstar system is intended to provide the National Command Authorities, chief military commanders, and strategic and tactical military forces with a highly protected and survivable means of communications that would be operable nearly worldwide and throughout all levels of military conflict.1 The Milstar program involves the acquisition of satellites; a mission control capability; and specially designed Army, Navy, and Air Force terminals for a variety of users operating from ground-mobile vehicles, ships, submarines, aircraft, and fixed-ground locations. As you requested, we evaluated (1) the Milstar system’s capabilities to support strategic and tactical missions and (2) the extent to which DOD has provided assurance of continuing comparable satellite communications among the users after the Milstar satellites under development are launched. Background DOD initiated the Milstar program under Air Force management in the early 1980s. Milstar is intended to be DOD’s most robust communications satellite system. It is designed to operate in the extremely high frequency (EHF) radio spectrum, although it has super high frequency and ultra high frequency capabilities, and it was originally designed to transmit signals at low data rates (LDR).2 Milstar employs computer processing capabilities on the satellites and several different radio signal processing techniques that provide resistance to electronic jamming. -

The Global Positioning System

The Global Positioning System Assessing National Policies Scott Pace • Gerald Frost • Irving Lachow David Frelinger • Donna Fossum Donald K. Wassem • Monica Pinto Prepared for the Executive Office of the President Office of Science and Technology Policy CRITICAL TECHNOLOGIES INSTITUTE R The research described in this report was supported by RAND’s Critical Technologies Institute. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data The global positioning system : assessing national policies / Scott Pace ... [et al.]. p cm. “MR-614-OSTP.” “Critical Technologies Institute.” “Prepared for the Office of Science and Technology Policy.” Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-8330-2349-7 (alk. paper) 1. Global Positioning System. I. Pace, Scott. II. United States. Office of Science and Technology Policy. III. Critical Technologies Institute (RAND Corporation). IV. RAND (Firm) G109.5.G57 1995 623.89´3—dc20 95-51394 CIP © Copyright 1995 RAND All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from RAND. RAND is a nonprofit institution that helps improve public policy through research and analysis. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of its research sponsors. Cover Design: Peter Soriano Published 1995 by RAND 1700 Main Street, P.O. Box 2138, Santa Monica, CA 90407-2138 RAND URL: http://www.rand.org/ To order RAND documents or to obtain additional information, contact Distribution Services: Telephone: (310) 451-7002; Fax: (310) 451-6915; Internet: [email protected] PREFACE The Global Positioning System (GPS) is a constellation of orbiting satellites op- erated by the U.S. -

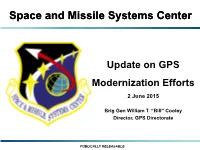

Update on GPS Modernization Efforts 2 June 2015

Space and Missile Systems Center Update on GPS Modernization Efforts 2 June 2015 Brig Gen William T. “Bill” Cooley Director, GPS Directorate PUBLICALLY RELEASABLE UNCLASSIFIED GSSAP SSA DSP DSCS COMMERCIAL COMM SBIRS WGS GEO MILSTAR Geostationary Earth Orbit GPS-III Optimal for (FUTURE) AEHF GPS-IIF Continuous Comm GPS-IIRM GPS-IIR GPS-IIA MEO Medium Earth Orbit Optimal for Global positioning, navigation & timing POLAR Optimal for DMSP Sun Sync/Global Weather ORS-1 Weather LEO Low Earth Orbit Optimal for Earth Sensing MILLSTONE HAYSTACK SBSS-10 • CCS SSA • SPACETRACK JMS VAFB AMOS GEODSS (NM) • GEODSS (DG) Eglin Radar • GEODSS (HI) • SPACE FENCE AFSCN GROUND STATIONS – Global Satellite Control C-Band Indian Ocean Micronesia Pacific Ocean Vandenberg AFB New Boston, NH Thule Air Base RAF Oakhanger CCAFS SST (AUS) DGS “REEF” GTS “GUAM” HTS “HULU” VTS “COOK” NHS “BOSS” TTS “POGO” TCS “LION” AEHF = Advanced Extremely High Frequency System, AFSCN = Air Force Satellite Control Network, CCAFS = Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, DMSP = Defense Meteorological Satellite Program, DSCS = Defense Satellite Communications, DSP = Defense Support Program System, EPS = Enhanced Polar System, GEODSS = Ground-based Electro-Optical Deep Space Surveillance System, GPS = Global Positioning System, GSSAP = Geosynchronous Space Situational Awareness Program, JSpOC = Joint Space Operations Center, ORS = Operationally Responsive Space, SBIRS = Space-Based Infrared System, SBSS = Space-Based Space Surveillance system, SSA = Space Situational Awareness, SST = Space